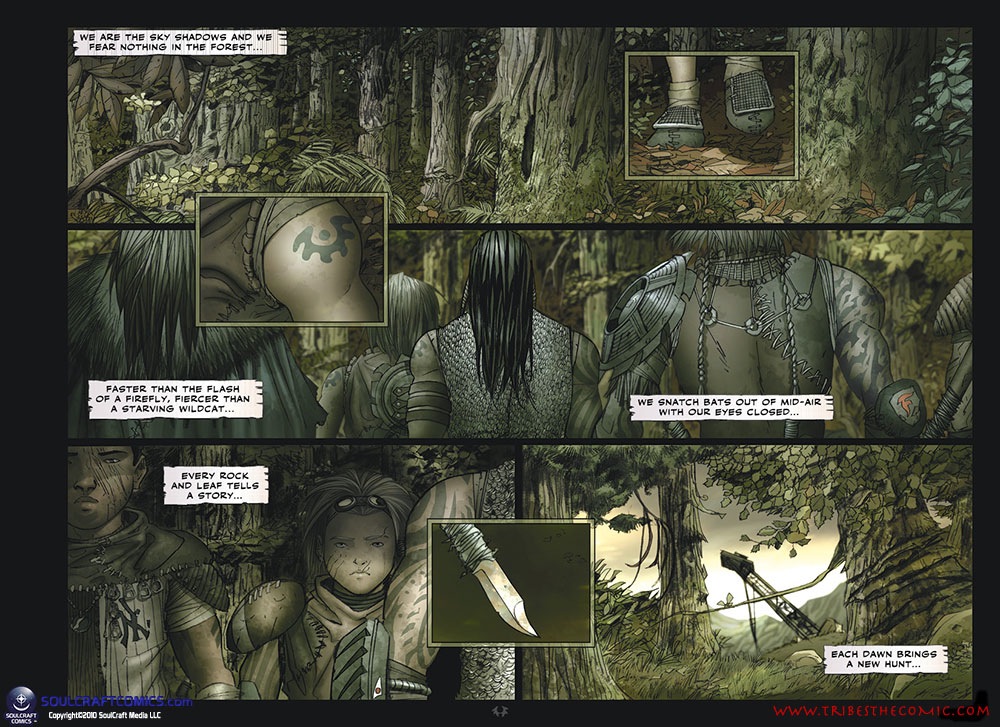

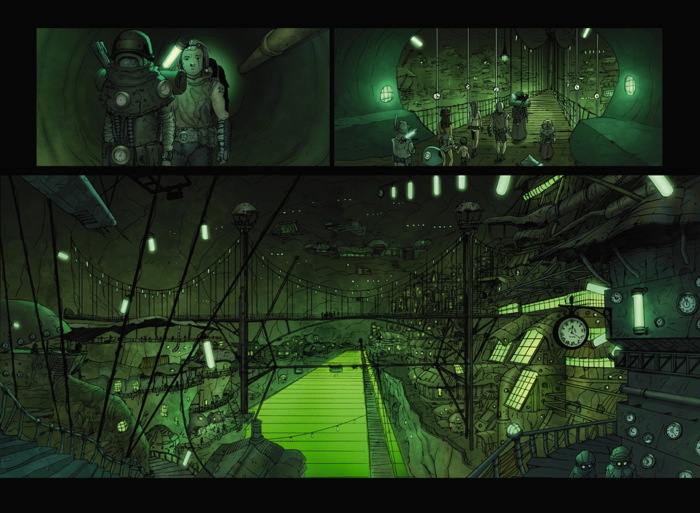

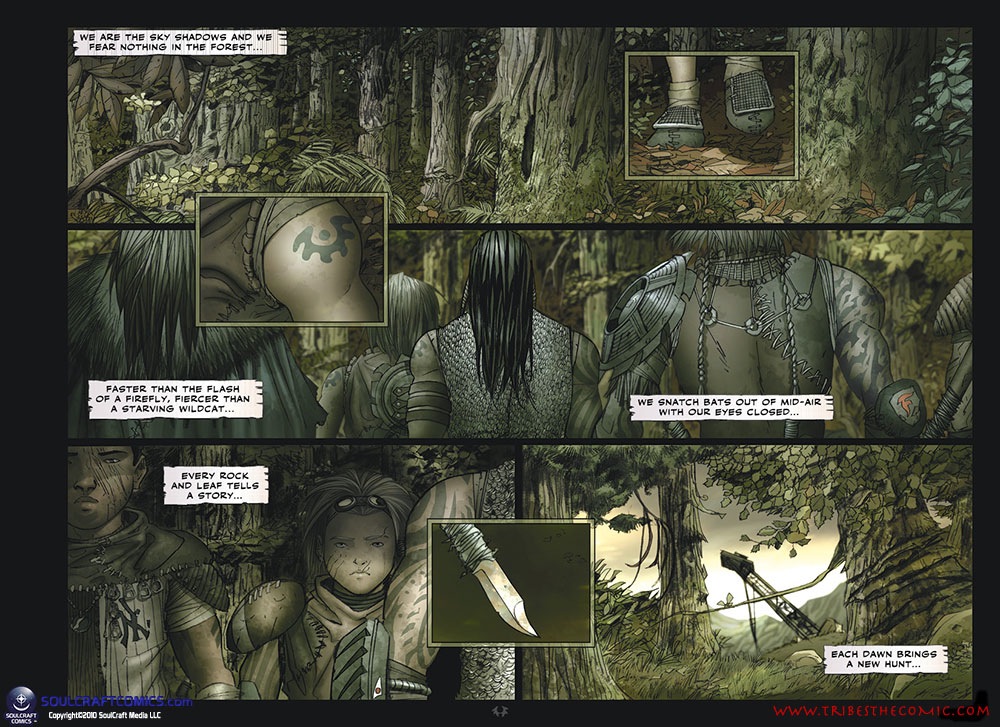

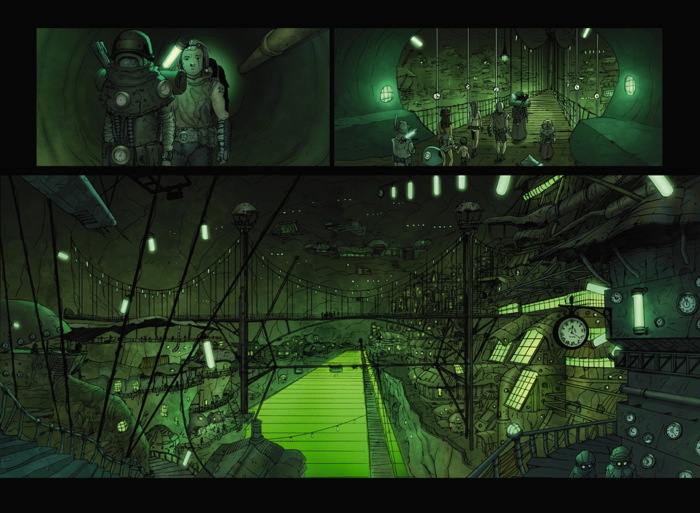

TRIBES the Dog Years is a SF graphic novel about a world where no one lives past the age of 21, that originally came out a few years ago. Written by Mike Geszel and Peter Spinetta, it featured gobsmacking art by Spanish artist Inaki Miranda, as seen on the book’s FB page. Paul Pope called it “Mad Max by way of Disney. Inaki draws with a widescreen vision that jumps off the page.”

Since Miranda has gotten better known since then do to all his work for Vertigo— including Coffin Hill—a new hardcover edition of the book is being released this May, Tribe: The Dog Years Deluxe Edition , for those who might have missed it the first time. The new edition will includes more concept designs, 20+ pages of original pencils, a newly designed cover and backing – all the unusual but effective horizontal format of the original. The edition includes an intro by screenwriter Alex Tse (Watchmen.)

, for those who might have missed it the first time. The new edition will includes more concept designs, 20+ pages of original pencils, a newly designed cover and backing – all the unusual but effective horizontal format of the original. The edition includes an intro by screenwriter Alex Tse (Watchmen.)

In the near future, a nano-virus accidentally shortens the human lifespan to 21 years. Two hundred years later, tribes of kids survive amidst the junkyard ruins of the techno-industrial age. One day everything changes for Sundog of the Sky Shadows tribe. Is there new hope for longer life? Can the virus be cured with the help of a mysterious “Ancient” from a city under the sea?

Miranda is really one of the most underrated artists around — his world building is second to none, and Tribes is a fine example of that. The book is in Previews now.

4.5 Stars Back Cover: The boy belongs to the Sauk tribe, the last Native Americans to live east of the Mississippi River. He learns survival skills from other tribal members. He witnesses the introduction of horses and the influx of white men using steel traps instead of wood and rawhide snares to capture fur-bearing animals. [...]

By Stephen Pevar

Chiefs at Verde Reservation, Arizona. Source: NYPL Labs Stereogranimator.

How would you feel if the government confiscated your land, sold it to someone else, and tried to force you to change your way of life, all the while telling you it’s for your own good? That’s what Congress did to Indian tribes 125 years ago today, with devastating results, when it passed the

Dawes Act.

During the 1800s, white settlers moved west by the tens of thousands, and the US cavalry went with them, battling Indian tribes along the way. One by one, tribes were forced to relinquish their homelands (on which they had lived for centuries) and relocate to reservations, often hundreds of miles away. By the late 1800s, some three hundred reservations had been created.

The purpose of the reservation system was, for the most part, to remove land from the Indians and to separate the Indians from the settlers. Reservations were usually created on lands not (yet) coveted by non-Indians. By the late 1800s, however, settlers were nearly everywhere, and Congress needed to develop a new strategy to prevent further bloodshed.

The government decided that instead of separating Indians from white society, Indians should be assimilated into white society. Assimilation of the Indians and the destruction of their reservations became the new federal goal.

Two very different social forces helped shaped this new policy: greed and humanitarianism. Many whites wanted Indian land and knew that they would have an easier time obtaining it if Indian tribes disappeared. This greed prompted Congress to pass the Dawes Act, also known as the General Allotment Act, in February 1887. The Dawes Act was also favored by many non-Indian social reformers who were aware that Indians were suffering unmercifully under the government’s existing reservation policies, and they sincerely believed that the best way to help Indians overcome their plight and their poverty was by encouraging assimilation. Although their motives differed, both groups pressured Congress to pass the Dawes Act. The objectives of the Act, as the US Supreme Court has noted, “were simple and clear cut: to extinguish tribal sovereignty, erase reservation boundaries, and force the assimilation of Indians into the society at large.” Indian tribes had no say in the matter and were not even consulted.

Most Indian tribes had no concept of private land ownership. Rather, land was communally owned and everyone worked together to gather what they could from the land and shared its bounty. In order to compel assimilation of the Indians, a scheme was developed that would undermine Indian life and culture at its core: individual Indians would be forced to own land for private use. Indians would be converted into capitalists.

To accomplish the new policy of assimilation, the Dawes Act authorized the President of the United States to divide communally-held tribal lands into separate parcels (“allotments”). Each tribal member was to be assigned an allotment and, after a twenty-five-year “trust” period, would be issued a deed to it, allowing the owner to sell it. Once the allotments were issued, the remaining tribal land (the “surplus” land) would be sold to non-Indian farmers and ranchers. Congress hoped that by allowing non-Indians to live on Indian reservations, the goals of the settlers and those of the humanitarian social reformers could both be satisfied: land would become available for non-In

Yesterday, we announced that South Sudan is the 2011 Place of the Year. How much do you know about Sudan, South Sudan, and Darfur? Test your knowledge with this quiz by Andrew S. Natsios.

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-time Indianby Sherman Alexie

YA

It's a bit daunting to review a book that's won the National Book Award. I mean, does it get any better than that? Okay, there is the Pulitzer, or maybe the Nobel Prize, but hey, this is the National Book Award. Wow.

Does Alexie live up to the hipe?

In a word, yes.

This is a character driven piece about a topic - reservation life and the hopelessness it breeds - that, in this generation, is little spoken about. Alexie brings it to life in a deeply emotional way. Death, alcoholism, hopelessness. Love, family, tribal bonds. Heavy topics handled with an honesty that makes the emotional cartharsis at the end of the piece feel very real.

This isn't about fixing the mess the U.S. created when it set up reservations. It isn't about doing away with reservations, or rethinking them. It's about one boy, Junior's, journey to create a new life for himself, a life with hope. It's about his love for his family. His love for his friends. And how he straddles two worlds to become one person. At the same time, his experiences aren't so heart-wrenching you'll be looking into Prosac by the time you're done. It's good, well thought-out, clean writing.

If you feel like honesty, like a solid read, like letting literature change you, read

True Diary. Junior lives up to his potential and beyond.

And for more fun and exciting tales, hop over to

Barrie Summy's website for the complete list of The Book Review Club's reviews this month!

, for those who might have missed it the first time. The new edition will includes more concept designs, 20+ pages of original pencils, a newly designed cover and backing – all the unusual but effective horizontal format of the original. The edition includes an intro by screenwriter Alex Tse (Watchmen.)