new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: guatemala, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 8 of 8

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: guatemala in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Marissa Wasseluk,

on 9/19/2016

Blog:

First Book

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

community,

Diversity,

Books & Reading,

Authors & Illustrators,

culture,

Guatemala,

America,

English,

immigrants,

Korea,

Anne Sibley O'Brien,

Somalia,

TESOL,

Stories for All,

Expert Voices,

I'm New Here,

welcoming week,

Add a tag

Welcoming Week is a special time of year. Communities across the country will come together to celebrate and raise awareness of immigrants, refugees and new Americans of all kinds. Whether it’s an event at your local art gallery or showing support on social media, the goal is to let anyone new to America know just how much they are valued and welcomed during what is likely a big transition.

And the biggest transitions are happening for the littlest people.

A new country, a new home, maybe even a new language — that would be enough for any kid — but a new school, too? That subject is exactly what author Anne Sibley O’Brien addresses in her book I’m New Here, new to the First Book Marketplace.

Marissa Wasseluk and Roxana Barillas of the First Book team had the pleasure of speaking with Anne about I’m New Here, the experiences of kids new to America, and what kids can do to help create a welcoming atmosphere.

Marissa: So, and I am sure you get this question all the time, but I’m curious — what inspired or motivated you to create I’m New Here?

It’s funny, it’s such a, “where would you start?” kind of question, but I don’t remember if anyone has ever asked me that point blank because I don’t recall ever putting together this answer before. Over the years of working in schools — especially working with Margy Burns Knight with our nonfiction books: Talking Walls; Who Belongs Here and other multi-racial, multicultural, global nonfiction books — I had a lot of encounters, a lot of discussions, a lot of experiences with immigrant students and I was very aware of the kinds of cross-cultural challenges that children and teachers can experience. For instance, Cambodian children show respect by keeping their eyes down and not looking in the eyes of an adult, especially a teacher. In Cambodian culture adults don’t ever touch children’s heads. So you can immediately imagine how those kinds of things would be quite challenging when a Cambodian child comes into a U.S. classroom and suddenly two of those cultural markers are not only gone, but the opposite is what they need to learn.

Somebody might put their hand on your head — it being out of concern and wanting to make a connection — or they might say “I need you to look at me now” and not recognize that that’s cultural inappropriate for a Cambodian child. So growing that kind of awareness of the challenges that immigrant children face — that was the original impetus for the book. Just collecting some of those stories and raising awareness of how many obstacles immigrant children face. From climate to traditions in speaking and in body language, to food, to learning a new language. Not just learning a new language in terms of how you speak and read and write, but also how you interact with people, how social norms work — they just face such enormous challenges. And there were originally six characters so it was trying to cover everything.

Marissa: The characters that are in the book, they cover a child from Guatemala, a child from Korea, and a child from Somalia — did you work with these specific immigrant communities when you were creating this book?

I spoke to individual experts, such as several Somali interpreters and family liaison experts who work for the multi-lingual, multicultural office of the Portland, ME public schools. So I had that kind of expert advice to respond to what I was writing. But the original ideas mostly came from my observations, my interactions with Somali students in the classrooms that I visited. And then with Korean students I met many, many Korean students here in the US and I had my own background to draw on there.

Marissa: Can you tell me a little bit more about these classrooms that you’ve visited? We talk with a lot of educators who work with Title I schools and they often talk about how reserved the English as a second language students can be. There is a silent phase that a lot of kids go through. Have you observed that and have you shared your book with any of these first generation immigrants?

It’s certainly been shared with many. I actually just shared it with a group of students in a summer school program — about seventy students from third to fifth grade who were from East African countries and some Middle Eastern countries. Most of the group were immigrants and I read the book and then we had a discussion about being new and being welcoming. Of all the student groups that I’ve worked with, they were actually the most effusive and had the most to share in that discussion about what it feels like to be new and what you can do to welcome someone.

Marissa: What were some of the suggestions?

They had all kinds of ideas about what you could say and do to make somebody feel like they were at home. You could take them around, go through a list and say, “this is your classroom, this is your teacher, this is your playground, this is your classmate.”

Roxana: You’re taking me back – a few years back I came to the United States when I was twelve from El Salvador, speaking no English. It hits close to home in terms of the importance of the work you are doing, not just for kids who may not always feel like they belong, but also for the kids who can actually help that process be an easier one.

That is wonderful to hear. I was just struck that they had more suggestions than any group I’d worked with, they could hardly be contained. They had so much they wanted to say and I think it’s very fresh in their minds what welcoming looks like and maybe what did or what didn’t happen for them. So the list that they wrote: welcome to my class, say hi, wave, smile, hello, say this is my classroom, these are my friends, do you want to become friends? these are my parents, this is my family, show them around, this is my chair, this is my house, this is your school, this is my teacher, can you read with me? how’s it going? I live here, where do you live? do you need help? welcome to my school.

That is wonderful to hear. I was just struck that they had more suggestions than any group I’d worked with, they could hardly be contained. They had so much they wanted to say and I think it’s very fresh in their minds what welcoming looks like and maybe what did or what didn’t happen for them. So the list that they wrote: welcome to my class, say hi, wave, smile, hello, say this is my classroom, these are my friends, do you want to become friends? these are my parents, this is my family, show them around, this is my chair, this is my house, this is your school, this is my teacher, can you read with me? how’s it going? I live here, where do you live? do you need help? welcome to my school.

It was the specificity of it that I just loved.

And they said what it felt like to be new. These kids went beyond with the details so they said: scared, nervous, confused, happy, sad, lonely, shy, surprised. Which is what I get with any group that I talk to — but then they wrote: don’t know how to write, don’t know everybody, don’t know what to do, don’t know what they’re saying, don’t know what to say, don’t think you fit in, embarrassed, don’t know how to read books, don’t know what to think, don’t know how to play games, don’t know how to respond, don’t know how to use the computer. So that is a really rich, concrete list.

Marissa: What about educators, how have educators responded to your book?

It’s been pretty phenomenal. The book is in its third printing and it’s just a year old. Actually, it went into its third print run in June. That is by far the fastest that any book of mine has taken off, so there seemed to really be a hunger. There are quite a number of books about an individual immigrant’s story, but I think what people are responding to, what they found useful, is that this book is different because it’s a concept book about the experience of being new and being welcoming, and in that way it works. A particular story can make a deep connection even if your experience is quite different, you recognize things that are similar. But to have one book that outlines what the experience is like, it is very good for discussions. I’ve done more teacher conferences and appearances, especially in the TESOL community, than I did before. Normally I do a lot of schools where I talk to students, but in the past year the majority of my appearances have been for teacher conferences.

Marissa: Have any of them come up to you and told you how it’s resonated with them? Have you met any educators who are immigrants themselves?

Yes, definitely! The TESOL community is full of people who have immigrant backgrounds. I shouldn’t say full, but there is quite a healthy percentage of the TESOL community who come from that background themselves. Partly because schools often recruit someone who’s bilingual, so you tend to get a lot of wonderful richness of people’s life experiences. They might be second generation or they might not have come as a child but they definitely make a strong connection to children who have that experience. I remember, in particular, some very moving statements that people made standing in line waiting to have a book signed. Talking about how it was “their story” or people talking about and being reminded of their own students. When I talked about the book they were in tears thinking about their own students.

Marissa: Ideally, how would you like to see your book being used in a classroom or a child’s home?

I think I see it in two ways. First, for a child who has just arrived and who is in a situation where things are strange; to be able to recognize themselves and see that their experience is reflected in something that makes them feel less lonely and that there is hope. Many, many people have gone through this experience and it can be so difficult but you can get through.

And to the children who are not recent immigrants, who have been part of a community for generations; that it would spark empathy for children, for them to imagine what it would be like if they had that experience. Starting with that universal experience of somehow being new somewhere and to recognize, “oh, I remember what that felt like” and imagine if it was not only a new school, but a new country and a new language and a new culture and new food and new religions and on and on and on. Particularly for them to imagine what they could do, concretely, to examine what the new children are doing and to see how hard they are working, the effort that they are making. And also how their classmates are responding so that the outcome is the whole group building a community together.

To learn more about I’m New Here and Anne’s perspective, watch and listen as she discusses the book and her insights into the experiences of immigrant children.

The post Welcoming Week: Q&A with Author Anne Sibley O’Brien appeared first on First Book Blog.

By: Celine Aenlle-Rocha,

on 9/24/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Music,

guatemala,

Music History,

broadway,

senegal,

*Featured,

xylophone,

instrument of the month,

American musicals,

Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments,

marimba,

Add a tag

You'd probably recognize the rainbow-patterned, lap-size plastic xylophone in the playroom, popular among music-minded toddlers. But what do you know about the real thing? The xylophone is a wooden percussion instrument with a range of four octaves, and can be used in a variety of musical genres.

The post Ten fun facts about the xylophone appeared first on OUPblog.

Eder Castillo: Mecánica Nacional (vista exterior) Artistas/Videos: Jason Mena: Fault Line (línea de falla), Eder Castillo: Mecanica Nacional, Karmelo Bermejo: -X, Guillermo Vargas “Habacuc”: Persona sin educación formal caminando con zancos hechos de libros apilados, Nadia Granados “la Fulminante”: La Fulminante Detonando Montreal / Cabaret Callejero, Victor Hugo Rodriguez “Crack”: Planas, Andrea Mármol: Otros Paramos / Julia, Jorge Linares: Trafico Aéreo Las [...]

By: AlyssaB,

on 8/3/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Religion,

Politics,

minors,

Current Affairs,

guatemala,

Nicaragua,

El Salvador,

Central America,

Humanities,

illegal immigration,

Honduras,

*Featured,

undocumented,

border security,

God and Gangs in Central America,

Homies and Hermanos,

Robert Brenneman,

undocumented youth,

brenneman,

Add a tag

By Robert Brenneman

Both the President and Senate Republicans have recently weighed in on what to do about the “surge” in undocumented minors arriving at the US border. Many of these undocumented youth come from the northern countries of Central America: Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. Embedded in most arguments about what ought to be done are assertions about what prompted these minors to set out in the first place and what will become of them if they stay. But many of these assumptions miss the mark and the truth is a lot more complicated than the sloganeering that characterizes much of the debate.

Myth #1: The increase in migrating minors came about as a result of the rise of gang violence in Central America.

Gang violence in Central America is real and it has touched the lives of far too many Central American youth and families. But the gangs have been a major feature of urban life since at least the late 1990s and there is little evidence to argue that gangs have increased in strength, size, or activity during the past three years. Meanwhile, the increase in migration of minors has been stratospheric. Undeniably, some of the youth heading north are escaping gang violence or threats from the gangs, but even the UN’s special report Children on the Run found, after conducting interviews with a scientific sample of detained youth, that just under a third of the youth mentioned the gangs as a factor contributing to their decision to leave. Most of the youth citing gangs were from El Salvador and Honduras.

Myth #2: Violence is spiraling out of control throughout Central America.

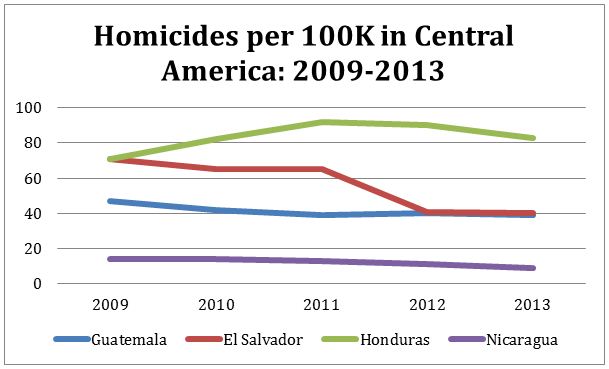

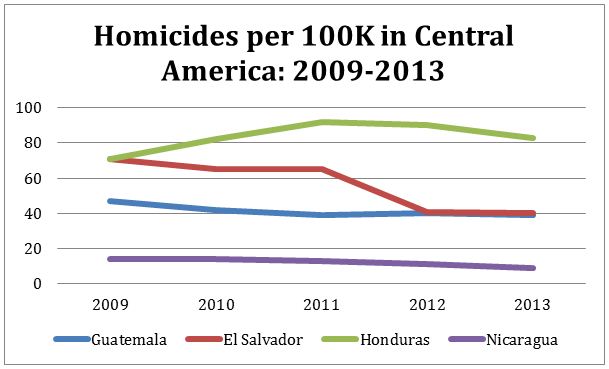

Although they share a number of important characteristics, the governments of Central America have taken different paths in how to relate to gangs, drugs, and violent crime. These divergent policies have contributed to very distinct outcomes. Notably, Nicaragua, which never took an “iron fist” approach to the gangs, has a far lower homicide rate and lower gang membership than its neighbors to the north. But even Guatemala, which has been well-known for homicidal violence ever since the state-sponsored violence of the 1980s, has shown improvement in its violent crime rate. Homicides have generally declined in recent years, probably as a partial result of Guatemala’s efforts to improve its justice system. As the chart below illustrates, Honduras has more than double the homicidal violence of its neighbors:

Myth #3: Coyotes (sometimes called “human traffickers”) are “tricking” children into migrating by telling them that they will receive citizenship upon arrival in the United States.

This myth reveals the utterly low regard in which many North Americans hold the intelligence of Central Americans. Oscar Martinez, an award-winning investigative journalist from El Salvador, recently published a fascinating account of his interview with a Salvadoran coyote who has been guiding his compatriots to El Norte since the 1970s. (Oscar knows about migrating minors — he has written a celebrated book about his trips across Mexico in the company of Central American migrants.) Among other myths effectively debunked in that interview is the notion that Central Americans hold wildly optimistic views about Border Patrol and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). In fact, most Central American youth and their relatives living in the United States are well aware that in all likelihood, they will, at best, become undocumented immigrants. But better to be close to family than suffer years of hardship while separated from parents, many of whom cannot travel “back” to their country of origin because of their own undocumented status. Of course, some of these youth are also escaping violence and the threat of violence as well as economic hardship and the crushing humiliation of living in generational poverty in some of the most unequal societies in the hemisphere. Thus, there are multiple factors at play when Central American youth (and their parents) consider whether or not to pay the US$7,000 charged by most coyotes for “guidance” across Mexico and over the US border. But few arrive under the illusion that they will attain legal status any time soon.

Myth #4: Central American youth who manage to stay in the United States as undocumented persons are likely to become part of a permanent underclass who represent a perpetual drain on the US economy.

Political conservatives often argue that our economy simply cannot sustain the weight of more undocumented Mexicans and Central Americans. In fact, research at the Pew Hispanic Center shows that 92% of undocumented men are active in the labor force (a higher proportion than among native men) and that most undocumented immigrants see modest improvements in their household income over time. Not surprisingly, those who eventually obtain legal status show far more substantial gains in their income and in the educational attainment of their children.

Myth #5: The situation in Central America is hopeless.

While it is true that many of the children who reach the US border have grown up in difficult and even dangerous situations and ought to be granted a hearing to determine whether or not they should be granted asylum, I have Central American friends (including some from Honduras) who might bristle at the suggestion that every child migrating northward is escaping life in hell itself. The idea that all Central American minors ought to be pronounced refugees upon arrival at the border rests on the mistaken assumption that these nations are hopelessly mired in violence and chaos, and it encourages the US government to throw in the towel with regard to advocating for economic and political improvements in the region.

True, a great deal of violence and hopelessness persists in the marginal urban neighborhoods of San Salvador and Tegucigalpa, but these communities did not evolve by accident. They are the result of years of under-investment in social priorities such as public education and public security compounded by the entrance in the late 1990s of a furious scramble among the cartels to establish and maintain drug movement and distribution networks across the isthmus in order to meet unflagging US demand. At the same time as we work to ensure that all migrant minors are treated humanely and with due process, we ought to use this moment to take a hard look at US foreign policy both past and present in order to build a robust aid package aimed at strengthening institutions and promoting more progressive tax policy so that these nations can promote human development, not just economic growth. It is time we take the long view with regard to our neighbors to the south.

Robert Brenneman is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Saint Michael’s College in Colchester, Vermont and the author of Homies and Hermanos: God and the Gangs in Central America.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Five myths about the “surge” of Central American immigrant minors appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 1/31/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

guatemala,

genocide,

Guatemala under General Efrain Rios Montt 1982-1983,

Judge Miguel Ángel Gálvez,

Rios Montt,

Terror in the Land of the Holy Spirit,

Virginia Garrard-Burnett,

montt,

guatemalans,

Religion,

Latin America,

*Featured,

Law & Politics,

General Efraín Ríos Montt,

Add a tag

By Virginia Garrard-Burnett

After the judge’s ruling Monday in Guatemala City, the crowd outside erupted into cheers and set off fireworks. The unthinkable had happened: Judge Miguel Ángel Gálvez had cleared the way for retired General Efraín Ríos Montt, who between 1982 and 1983 had overseen the darkest years of that nation’s 36-year long armed conflict, would stand trial for genocide. In that conflict (1960-1996), more than 150,000 Guatemalans died, the majority at the hands of their own government, which used their lives to prosecute a ferocious counterinsurgency war against a group of Marxist guerrillas who had hoped to bring a Sandinista-style socialist regime to Guatemala. For many, General Ríos Montt represented the face of this war, because it was during his short terms as president between March 1982 and August 1983 (he both came to power and was expelled in military coup d’états), that the Guatemalan army undertook the most bloody operation of the war, a violent scorched-earth campaign that not only nearly eliminated the guerrillas military operation, but which also killed many thousands of civilians, the vast majority of them Maya “Indians.” Now, some thirty years later, Ríos Montt will be prosecuted along with his former chief of intelligence, Mauricio Rodriguez Sánchez, for genocide and crimes against humanity. Specifically, he will be charged with ordering the killings of more than 1,700 Maya Ixil people in a series of massacres that the Army conducted in the northern part of the country in 1982.

The axiom “justice delayed is justice denied” notwithstanding, the prosecution of fatally misguided leaders and despots such as Serbia’s Radovan Karadžić or Hutu leader Beatrice Munyenyezi is not unusual in the early 21st century. Trials such as these are designed to serve the cause of justice, of course, but they are also instrumental in helping a traumatized society create a coherent narrative and build a collective historical memory around what happened in its recent past. What is unusual about the case against Ríos Montt is that almost no one foresaw the day when such a trial would ever take place in Guatemala. In large part, this stems from Guatemala’s long-standing culture of impunity, where few people, from common criminals all the way up to corrupt businessmen and military officers, are held accountable for their crimes; generally speaking, the rule of law there simply does not rule. Beyond that, Ríos Montt’s continued influence in the country—among other things, he established and headed a powerful political party, the Frente Republicano Guatemalteco in the 1989, and he run an unsuccessful campaign for president as recently as 2003—further mitigated against expectations for his prosecution. His daughter, Zury Ríos Montt (who is married to former US Congressman Jerry Weller) is a rising and powerful young politician; her support for her father is so absolute that she stormed out of the courtroom yesterday before the judge could finalize his pronouncement. But most of all, the prosecution of Ríos Montt seemed most unlikely because, in the strange paradox of power that sometimes comes with authoritarian regimes, there were, and still continue to be, some Guatemalans who continue to respect him, remembering his bloody rule as a time when one could walk the streets of the capital safely and when the “raging wolves” of communism were kept at bay.

Adding to the complexity of this case is that fact that, at the time he served as chief of state in the early 1980s, (although called “President,” he did not actually hold this title, having taken power in a coup), Ríos Montt was a newly born again Christian, a member of a neo-Pentecostal denomination called the Church of the Word (Verbo). Fresh from the rush of his conversion, Ríos Montt addressed the nation weekly during his term of office, offering what people called his “Sunday sermons,”—discourses in which he drifted freely from topics ranging from his desire to defeat the “subversion,” to advice on wholesome family living, to his particular vision of a “New Guatemala” where all peoples would live together as one (a jab at the unassimilated Maya), in compliant obedience to a benign government that served the general good. Ríos Montt’s dream of a New Guatemala was in many ways as elusive as quicksilver, and in his sermons, he made no mention of the carnage going on in the countryside. The sacrifice of the Maya people and other “subversives” was not at all too high a price to pay, in his estimation, for the New Guatemala.

But the elegance, even the peaceability of his language, along with his strong affiliation with the Church of the Word (his closes advisors were church leaders, not his fellow generals) in that moment made Ríos Montt the darling of the emergent leaders of the Christian Right in the United States who were coming of age during the presidency of Ronald Reagan. For them, as for the Reagan administration, Ríos Montt seemed to have emerged out of nowhere from the turmoil of the Central American crisis of the early 1980s as an anti-communist Christian soldier and ally. It seemed unthinkable to them that the same man who, with one hand, reached out to called for honesty and familial devotion from his people, would order the killing of his own people with his other. And so it seems to some Guatemalans even today. Yet the strong and irrefutable body of evidence that produced yesterday’s ruling tells a very different, and much more tragic story.

Virginia Garrard-Burnett is a Professor of History and Religious Studies at the University of Texas-Austin and the author of Terror in the Land of the Holy Spirit: Guatemala under General Efrain Rios Montt 1982-1983.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Ríos Montt to face genocide trial in Guatemala appeared first on OUPblog.

By:

Aline Pereira,

on 3/24/2008

Blog:

PaperTigers

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Amelia Lau Carling,

Holi,

Mina-s Spring of Colors,

Sawdust Carpets,

Children's Books,

events,

Picture Books,

Rachna Gilmore,

India,

Guatemala,

BBC,

Easter,

Time,

Books at Bedtime,

Add a tag

This year, unusually, feast days from many of the world’s religions have fallen around these last few days – so, as Time put it:

unlike some holy days — say, Christmas, which some non-Christians in the U.S. observe informally by going to a movie and ordering Chinese food — on this particular Friday, March 21, it seems almost no believer of any sort will be left without his or her own holiday…

Today I focus on two books, which each in their own way explore the celebration of one of these religious festivals against a different cultural background.

Mina’s Spring of Colors is a very special story about a young Indian girl who, although she now lives in Canada, is determined to throw a Holi party for her school-friends and neighbors: they won’t just watch the celebrations but participate in them. The book is aimed at 8-11 year olds, though younger children could enjoy having it read to them. It will certainly fill their heads with ideas about how to throw their own Holi party. The author Rachna Gilmore said in an interview with PaperTigers:

Mina’s Spring of Colors is a very special story about a young Indian girl who, although she now lives in Canada, is determined to throw a Holi party for her school-friends and neighbors: they won’t just watch the celebrations but participate in them. The book is aimed at 8-11 year olds, though younger children could enjoy having it read to them. It will certainly fill their heads with ideas about how to throw their own Holi party. The author Rachna Gilmore said in an interview with PaperTigers:

I have wonderful memories of Holi - memories of the physical excitement and dread and anticipation of getting others with coloured powders and water and also trying to dodge them in return, the shrieking, hysterical laughter and the wild delight. I don’t know of any readers who have put on a Holi party for themselves, but oh, I do hope some have. Kids love the idea and I know it would be an absolute blast. In one of the libraries I have visited to do a reading, the librarian was very keen on the idea, but of course, we couldn’t use coloured water and powder, so instead, we sprinkled each other with sparklies and squirted those cans that spurt multicoloured streamers. It was great fun.

There are some great pictures from this year’s celebrations in India here (and I can’t resist these from a couple of years ago too!); and you can find out more about Holi here.

Charlotte chose Amelia Lau Carling’s gorgeous, autobiographical picture-book Sawdust Carpets/Alfombras de aserrín  as the subject of her first post for the PaperTigers blog, back in May last year; and it’s well worth pointing it out now as a special book for Easter. It exemplifies a harmony of both diversity and fusion of cultures, as we learn about the celebration of Holy Week in Guatemala through the eyes of a young Amelia. Her parents had fled China during the Second World War and had made their new home in Guatemala, as described in Carling’s first book, Mama and Papa Have a Store. As well as insight into her family’s participation in the festivities, we learn about the incredible carpets made of dyed sawdust and millions of flower petals, which everyone joins in making to celebrate Easter:

as the subject of her first post for the PaperTigers blog, back in May last year; and it’s well worth pointing it out now as a special book for Easter. It exemplifies a harmony of both diversity and fusion of cultures, as we learn about the celebration of Holy Week in Guatemala through the eyes of a young Amelia. Her parents had fled China during the Second World War and had made their new home in Guatemala, as described in Carling’s first book, Mama and Papa Have a Store. As well as insight into her family’s participation in the festivities, we learn about the incredible carpets made of dyed sawdust and millions of flower petals, which everyone joins in making to celebrate Easter:

They are offered up as a sacrifice in anticipation of the procession that will destroy them by marching through the painstaking and fantastic creations.

So whatever you may have been celebrating these last few days, we send you best wishes – do tell us about any special traditions you have, from whatever part of the world you come from; and if you have any favorite books to recommend…

"At an all night cockfighting tournament in Huehuetenango, to which I'd gotten a ride with a man in a black SUV who'd accidentally, intentionally let hundred-dollar bills fall from his pocket when he reached for his money roll to buy a bear, it seemed like half of the people there had been to the United States and back."

"At an all night cockfighting tournament in Huehuetenango, to which I'd gotten a ride with a man in a black SUV who'd accidentally, intentionally let hundred-dollar bills fall from his pocket when he reached for his money roll to buy a bear, it seemed like half of the people there had been to the United States and back."

That's Brian Francis Slattery describing a real-life trip to Guatemala that inspired one of the most violent, vivid scenes in his novel, Spaceman Blues. Guatemala is one of my favorite places, and his travel writing nailed some dark and beautiful things about the country.

This first-time novelist is my special guest this week, and today he discusses the research and politics of immigration swirling around his novel.

Welcome to my deceptively simple feature, Five Easy Questions. In the spirit of Jack Nicholson's mad piano player, I run a weekly set of quality interviews with writing pioneers—delivering some practical, unexpected advice about web writing.

Jason Boog:

How did you convert your real-life travels through Guatemala into hallucinatory interludes in your novel? In other words, what's your advice for writers as they travel to new places, how can they capture the experience in a creative way like you did?

Brian Francis Slattery:

The parts that physically describe Guatemala I tried to do as accurately as I could; allusions to what happened during Guatemala's civil war are taken from what people there told me and from what I learned through reading about the place. Continue reading...

I've been waiting a whole year to tell you this: I'm going to Guatemala tomorrow.

I've been waiting a whole year to tell you this: I'm going to Guatemala tomorrow.

Don't worry, there's a special street storytelling version of Five Easy Questions being published while I'm gone, but I won't be answering emails for the next ten days.

In the meantime, I'd like to refer you to one of my favorite reporters.

Last year, Xeni Jardin spent a lot of time reporting in Guatemala for different magazines and in her personal blog. Guatemala is my favorite country in Central America. I lived there for two years in Peace Corps, but it's time for new stories.

No matter where we travel, all us fledgling writers should follow Jardin's example. Check out her five-part NPR series that shows an unexpected side of Guatemala:

"an overview of how innovative uses of technology are creating change in this Central American nation. From forensic scientists using DNA to identify death squad victims, to digital archivists preserving once-secret police documents from the civil war, to grassroots infrastructure tech providing electricity and clean water to Mayan villages."

Thanks to Xeni Jardin for the picture...

That is wonderful to hear. I was just struck that they had more suggestions than any group I’d worked with, they could hardly be contained. They had so much they wanted to say and I think it’s very fresh in their minds what welcoming looks like and maybe what did or what didn’t happen for them. So the list that they wrote: welcome to my class, say hi, wave, smile, hello, say this is my classroom, these are my friends, do you want to become friends? these are my parents, this is my family, show them around, this is my chair, this is my house, this is your school, this is my teacher, can you read with me? how’s it going? I live here, where do you live? do you need help? welcome to my school.

That is wonderful to hear. I was just struck that they had more suggestions than any group I’d worked with, they could hardly be contained. They had so much they wanted to say and I think it’s very fresh in their minds what welcoming looks like and maybe what did or what didn’t happen for them. So the list that they wrote: welcome to my class, say hi, wave, smile, hello, say this is my classroom, these are my friends, do you want to become friends? these are my parents, this is my family, show them around, this is my chair, this is my house, this is your school, this is my teacher, can you read with me? how’s it going? I live here, where do you live? do you need help? welcome to my school.