new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Lord Byron, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 10 of 10

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Lord Byron in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Maryann Yin,

on 10/15/2014

Blog:

Galley Cat (Mediabistro)

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Bill Gates,

Alan Turing,

Steve Jobs,

Lord Byron,

Doug Engelbart,

Marilynne Robinson,

Coming Attractions,

GalleyCat Reviews,

Ada Lovelace,

Walter Isaacson,

Steve Wozniak,

Larry Page,

Marie Lu,

Tim Berners-Lee,

J.C.R. Licklider,

John von Neumann,

Robert Noyce,

Vannevar Bush,

Add a tag

We’ve collected the books debuting on Indiebound’s Indie Bestseller List for the week ending October 12, 2014–a sneak peek at the books everybody will be talking about next month.

We’ve collected the books debuting on Indiebound’s Indie Bestseller List for the week ending October 12, 2014–a sneak peek at the books everybody will be talking about next month.

(Debuted at #2 in Hardcover Fiction) Lila by Marilynne Robinson: “Lila, homeless and alone after years of roaming the countryside, steps inside a small-town Iowa church—the only available shelter from the rain—and ignites a romance and a debate that will reshape her life. She becomes the wife of a minister, John Ames, and begins a new existence while trying to make sense of the life that preceded her newfound security.” (October 2014)

(more…)

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

By:

[email protected],

on 10/12/2014

Blog:

Perpetually Adolescent

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

art,

frankenstein,

mary shelley,

Lord Byron,

affirm press,

siri hustvedt,

Book Reviews - Fiction,

alex miller,

Joy Lawn,

Autumn Laing,

Blazing World,

Emily Bitto,

Percy Shelley,

The Strays,

Victorian Premier's Literary Award,

Add a tag

Who are the strays in Emily Bitto’s literary novel, The Strays (Affirm Press)? The new Melbourne Modern Art Group tries to set up a bohemian utopia paralleling Sunday and John Reed’s Heide group, or Norman Lindsay’s enclave, on affluent Evan and Helena Trentham’s property during the Depression. Patrick is a stalwart and Ugo, Maria and […]

By:

[email protected],

on 6/2/2014

Blog:

Perpetually Adolescent

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

literature,

art,

Pop Culture,

Wuthering Heights,

dracula,

frankenstein,

John Keats,

Percy Bysshe Shelley,

Lord Byron,

Weezer,

My Chemical Romance,

AFI,

AC/DC,

Book Reviews - Non-Fiction,

1001 Books you must read before you die,

craig schuftan,

Entertain Us,

Fredrich Nietzsche,

Hey! Nietzche! Leave Them Kids Alone!,

The Culture Club,

The Romantic Movement,

Triple J,

Add a tag

I’m not really interested in giving people a quick introduction; I tend to mix my personal life, humour, sarcasm and knowledge into my book reviews and blog posts. However I do want to kick off talking about the book that turned me into a reader. It wasn’t until 2009 that I discovered the joys of books and reading and something inside me clicked and I wanted to consume every book I saw. This life changing event was all because of one book, an Australian non-fiction title called Hey! Nietzsche! Leave Them Kids Alone! by Craig Schuftan.

I’m not really interested in giving people a quick introduction; I tend to mix my personal life, humour, sarcasm and knowledge into my book reviews and blog posts. However I do want to kick off talking about the book that turned me into a reader. It wasn’t until 2009 that I discovered the joys of books and reading and something inside me clicked and I wanted to consume every book I saw. This life changing event was all because of one book, an Australian non-fiction title called Hey! Nietzsche! Leave Them Kids Alone! by Craig Schuftan.

At the time I listened to a lot of music and would have cited AFI, My Chemical Romance, Weezer, and so on as some of my favourite bands. In face I was right into the music that was been played on Triple J. Craig Schuftan was a radio producer at Triple J at the time and there was a short show he made for the station called The Culture Club. In this show he would talk about the connection rock and roll has to art and literary worlds. Friedrich Nietzsche was claiming, “I am no man, I am dynamite” well before AC/DC’s song TNT.

That was a real revelation for me and I picked up Hey! Nietzsche! Leave Them Kids Alone! (subtitled; The Romantic Movement, Rock and Roll, and the End of Civilisation as We Know It) and began reading it. However it didn’t stop there; this book connected the so called ‘emo’ movement with The Romantic Movement, I never thought these bands would have anything in common with the greats like Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley or John Keats but I had to find out.

Hey! Nietzsche! Leave Them Kids Alone! by Craig Schuftan ended up taking half a year to complete; not because I was a slow reader but I wanted to know more,and I read poetry by Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley and John Keats, and researched online. I picked up books like Frankenstein (an obsession of mine), Dracula and Wuthering Heights just because they were mentioned. This was a weird turn in my life but my growing thirst for knowledge became an obsession with reading. I have now set a life goal to read everything on the 1001 Books you must read before you die list.

It is weird to think one book can have such a huge impact on my life but I credit Craig Schuftan (and my wife) for such a positive improvement in my life. I will eventually read Craig Schuftan’s books The Culture Club: Modern Art, Rock and Roll and other stuff your parents warned you about and Entertain Us!: The Rise and Fall of Alternative Rock in the Nineties but I’ve put them off because I suspect the same amount of research will be involved.

Has a book had such a positive impact in your life? I would love to know in the comments. Also are there any other books that explore the connections between art and literature with pop-culture?

By: Julia Callaway,

on 4/10/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

guitar,

john keats,

Shelley,

lord byron,

Samuel Taylor Coleridge,

keats,

romanticism,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

oxford journals,

Arts & Leisure,

Online products,

guitarists,

early music,

Christopher Page,

Giulianiad,

guitar history,

Romantic poets,

gresham,

Music,

Music History,

Add a tag

By Christopher Page

I am struck by the way the recent issue of Early Music devoted to the early romantic guitar provides a timely reminder of how little is known about even the recent history of what is to day today the most popular musical instrument in existence. With millions of devotees worldwide, the guitar eclipses the considerably more expensive piano and allows a beginner to achieve passable results much sooner than the violin. In England, the foundations for this ascendancy were laid in the age of the great Romantic poets. It was during the lifetimes of Keats, Shelley, Byron, and Coleridge, extending from 1772 to 1834, that the guitar rose from a relatively subsidiary position in Georgian musical life to a place of such fashionable eminence that it rivalled the pianoforte and harp as the chosen instrument of many amateur musicians.

What makes this rise so fascinating is that it was not just a musical matter; the vogue for the guitar in England after 1800 owed much to a new imaginative landscape for the guitar owing much to Romanticism. John Keats, in one of his letters, tellingly associates the guitar with popular novels and serialized romances that were shaped by the interests of a predominantly female readership and were romantic in several senses of the word with their stories of hyperbolized emotion in exotic settings. For Byron, a poet with a wider horizon than Keats, the guitar was a potent image of the Spanish temper as the English commonly imagined it during the Napoleonic wars and long after: passionate and yet melancholic, lyrical and yet bellicose in the defence of political liberty, it gave full play to the Romantic fascination with extremes of sentiment. For Shelley in his Poem “With a Guitar,” the gentle sound of the instrument distilled the voices of Nature who had given the materials of her wooded hillsides to make it, but it also evoked something beyond Nature: the enchantment of Prospero’s isle and a reverie reaching beyond the limitations of sense to “such stuff as dreams are made on.” As the compilers of the Giulianiad, England’s first niche magazine for guitarists, asked in 1833: “What instrument so completely allows us to live, for a time, in a world of our own imagination?”

Given the wealth of material for a social history of the guitar in Regency England, and for its engagement with the romantic imagination, it is surprising that so little has been written about the instrument. It does say something about why England is widely regarded as the poor relation in the family of guitar-playing nations. The fortunes of the guitar in the early nineteenth century are commonly understood in a continental context established especially by contemporary developments in Italy, Spain, and France. To some extent, this is an understandable mistake, for Georgian England received rather more from the European mainland in the matter of guitar playing than she gave, but it is contrary to all indications. But we may discover, in the coming years, that the history of the guitar in England contains much that accords with that nation’s position as the most powerful country, and the most industrially advanced, of Western Europe at the close of the Napoleonic Wars.

There is so much material to consider: references to the guitar and guitarists in newspapers, advertisements, novels, short stories, poems and manuals of deportment, the majority of them published in the metropolis of London. The pictorial sources encompass a great many images of guitars and guitarists in a wealth of prints, mezzotints, lithographs, and paintings. The surviving music comprise a great many compositions for guitar, both in printed versions and in manuscript together with tutors that are themselves important social documents. Electronic resources, though fallible, permit a depth of coverage previously unattainable. Never have the words of John Thomson in the first issue of Early Music been more relevant: we set out on an intriguing journey.

Christopher Page is a long-standing contributor to Early Music. A Fellow of the British Academy, he is Professor of Medieval Music and Literature in the University of Cambridge and Gresham Professor of Music elect at Gresham College in London. In 1981 he founded the professional vocal ensemble Gothic voices, now with twenty-five CDs in the catalogue, from which he retired in 2000 to write his most recent book, The Christian West and its Singers: The first Thousand Years (Yale University Press, 2010).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: Courtesy of Christopher Page. Do not use without permission.

The post The early history of the guitar appeared first on OUPblog.

Happy Lord Byron’s Birthday! The 224th this year. The book I’m working on is about him, which is how I know; but even if you haven’t been spending an inordinate amount of time thinking/writing about a long-dead Romantic poet, his birthday would make a great, wider holiday. I wish it’d catch on, possibly in lieu of some other winter holiday that’s either dull (Presidents’ Day) or mostly makes people unhappy (Valentine’s). So many ways to observe it. Ill-advised sleeping around, most obviously; pistol-shooting around the house; planning elaborate burial tombs for one’s pets; commissioning a Napoleonic carriage (or equivalent) and taking it abroad without ever paying for it; etc. etc. I wasn’t sure how I’d celebrate, but this morning settled on a mall trip for some Touche Éclat — as purchase of overpriced item bought in vain (both senses of the word) hope of staving off 40-something inevitableness of looking like I’ve been up all night being ass-reamed by a family of giant squid seems right in line with the spirit of the day.

By:

Claudette Young,

on 10/3/2011

Blog:

Claudsy's Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Bible,

Writing and Poetry,

Frankenstein,

Mary Shelley,

Lord Byron,

John William Polidori,

Yahoo! News,

Texas State University–San Marcos,

Villa Diodati,

Add a tag

Astronomers released a new report this past week. http://news.yahoo.com/under-frankenstein-moon-astronomer-sleuths-solve-mary-shelley-201601341.html/

Rumor has it that these researchers play with scientific private investigation in their spare time. They snag one literary allusion at a time, hoping to find the possible authentic astronomical event to which it refers.

“A group of astronomers used some crafty celestial sleuthing to put to rest a 19th Century mystery surrounding the events that inspired Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, author of the classic novel “Frankenstein,” to pen her tragic tale of the infamous monster.

Astronomers from Texas State University-San Marcos delved into Shelley‘s own description of what moved her to write the legendary story, in hopes of solving a long-standing controversy over whether the account is true, or if the author took some liberties in her re-telling of what happened.”

This new investigation report deals with Mary Shelley’s assertion that she witnessed the full moon from her bedroom window and “…had a waking dream” in which the story of Frankenstein came to her fully realized. Consider for the moment how minor that singular statement really is. It’s peculiar that such a controversy would surround it for two centuries, but it has.

If these researchers spend their spare time investigating such allusions throughout literature to find the truth of them, how long does it take to get all the evidence Yay or Nay on a given investigation? When one thinks of the sheer numbers of such literary statements used over the years, it’s easy to understand that these intrepid scientists will never go without a project that fascinates them.

What does an investigator look for? The creative non-fiction world of writing alone is a treasure chest filled with bits and pieces of factoid information. Getting hold of someone else’s account of the event(s) written about would help to verify or negate said event. Journals and diaries work for this type of search.

Of course, the investigator would have to first identify those who would have witnessed the event. That could take years; depending on what year the event took place. Only after that could the scientist take the field, so to speak, to do the calculations necessary to validate whether the event might have happened during a specific or approximate date in time. Without that verification, the reader has no way to trust the story’s

2 Comments on Literature’s Scientific Investigators, last added: 10/4/2011

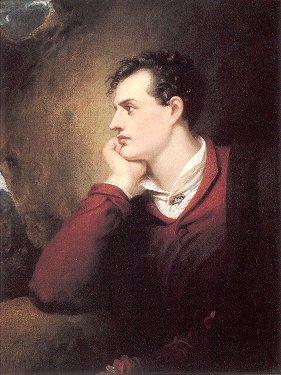

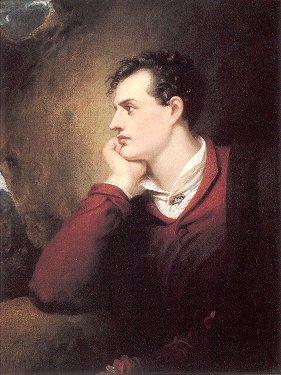

This is my old school. Posh, eh? (Oh all right, it was a comprehensive by the time I went, but it looks very smart.)

And out front, that's its most famous alumnus, Lord Byron. I passed him every morning and afternoon for six years (except during holidays and illness) and sadly, never appreciated him. All I knew of the man was that extraordinary sheet that makes him look not unlike Sally Bercow, and the fact that he was responsible for one of the songs on my mother's Alexander Brothers LPs. (Dark Lochnagar. If you know anything of the Alexander Brothers, you'll know that's no way to get to know a poem.) Oh, and the fact that I didn't get to be in Byron House (bunch of jessies).

Why didn't they tell us? Why didn't they tell us he was a rake, a rogue, a soldier of fortune, probably bisexual and incestuous, and that he actually looked like THIS?

Nom. Anyway, if I'd known he was as interesting as THAT, I wouldn't have walked past him every day with a roll of my eyes and my nose in a Marvel comic.

Maybe nowadays the students get, to paraphrase Horrible Histories, literature with the babe-a-licious bits left in. I hope so. Anyway, I remembered the old stone bloke the other day when reading Leslie Wilson's terrific

post about language and sex in young adult books. If he'd been around today, I'm sure the young scoundrel would have been a proud presence on many a banned books list.

Anyway, I wish I'd discovered Byron a lot earlier. I think I would have, if they'd left in the language and sex.

What's not to like?

www.gillianphilip.com

A NOTE ON UNFAITHFUL ENGLISH SPELLING AND THE HISTORY OF THE WORD GIAOUR

By Anatoly Liberman

Today hardly anyone would have remembered the meaning of the word giaour “infidel” (the spellchecker does not know it and, most helpfully, suggests glamour and Igor among four variants) but for the title of Byron’s once immensely popular 1813 poem: many editions; ten thousand copies sold on the first day, an unprecedented event in the history of 19th-century publishing. Nowadays, at best a handful of specialists in English romanticism and reluctant graduate students read it or anything else by this author—an unfortunate development. Yet if the word is still familiar to the English speaking public, it happens only thanks to Byron.

At the end of the 19th century, there was a heated discussion about the pronunciation of initial g- in giaour, and, as usual in such cases, conflicting suggestions about the origin of the word turned up. The OED had just approached the volume with giaour, and its verdict was eagerly awaited. Alas, no dictionary will save us from the ambiguity of initial g in Modern English. Only j can be relied upon: no one doubts how to pronounce jam, jet, jerk, jitters, Joe, or jumble, even when for historical reasons that make little sense to modern speakers j- renders what should have been y-, as in Jerusalem, Jericho, Jordan, and the like. But g- before i and e is a nightmare. We have begin (and Shakespeare often used this verb without the prefix and wrote gin, appearing in some of our editions with an apostrophe:’gin) and gin (the beverage), get and gem (alongside Jemima); gill (in a fish), gill “ravine” (both with “hard” g) and gill “half a pint,” as well as gill “lass,” that is, Jill (both with “soft” g). To increase the confusion, we are offered gild, guilt, age, ridge, wedge and Wedgwood (for completeness’ sake, compare rajah and the odd-looking transliteration hajj “pilgrimage’). It was deemed necessary to abbreviate refrigerator to fridge: frige, on an analogy with rage or fringe, did not suffice. If I received the mandate to reform English spelling, one of my first executive orders would have abolished this mess. Not hungry for power, except for power over words, and shirking administrative duties to the extent it is possible on a modern day campus, I think this is the one post I am longing for. But the coveted mandate will never come my way, and judging by what is happening in this area, nobody will. With regard to spelling, we are doomed to remain in the17th century at the latest.

There is no way of finding out how Byron pronounced giaour, though he probably said it with j-, as was more comm

(Venice, Italy) I nominate Andrea di Robilant for American Ambassador to Italy, or Italian Ambassador to the United States, whichever position becomes available first. He is an international treasure and should be paid a pot of gold and a rainbow to bridge the gap between the cultures. Son of an American mother and an Italian father, Andrea's ancestors also include two of the most ancient noble families in Venice, the Memmos and the Mocenigos. Most importantly, he has a tri-cultural sense of humor.

(Venice, Italy) I nominate Andrea di Robilant for American Ambassador to Italy, or Italian Ambassador to the United States, whichever position becomes available first. He is an international treasure and should be paid a pot of gold and a rainbow to bridge the gap between the cultures. Son of an American mother and an Italian father, Andrea's ancestors also include two of the most ancient noble families in Venice, the Memmos and the Mocenigos. Most importantly, he has a tri-cultural sense of humor.

That image you see is of Palazzo Mocenigo, and was shot by Carlo Naya back in the mid-1800s when photography was in its infancy. "The Lives of Spaces" was the name of Ireland’s participation at the 11th International Architecture Exhibition at La Biennale last year, and inspired my thought that Palazzo Mocenigo -- the space itself -- is a fertile backdrop for many Venetian stories right up until the present day. There's a whole lotta ghosts running around over there.

Last Monday, I heard Andrea speak in English over at UNESCO about his latest book, Lucia in the Age of Napoleon. (Sitting next to me at the lecture were the current tenants of Palazzo Mocenigo, which made it even more surreal, though I do believe they were human beings, not ghosts:) This past Monday evening I caught the end of Andrea's talk in Italian, Lucia nel tempo di Napoleone, over at Ateneto Veneto. The first talk was so entertaining, I immediately read the book (in English). Andrea had some fascinating ancestors who also happened to be clever writers.

This is from the Prologue:

When I was growing up I sometimes heard my grandfather mention Lucia Mocenigo, my Venetian great-great-great-great-grandmother, who was known in the family as Lucietta. Her name usually came up in connection with Lord Byron, to whom she rented the piano nobile of her palazzo during his scandalous time in Venice. I learnt more about her many years later, while doing research on her father, Andrea Memmo, whose epic love story with the beautiful Giustiniana Wynne in the 1750s was the subject of my last book, A Venetian Affair.

You regular readers might remember hearing about Andrea Memmo and Giustiniana Wynne (another fab female writer) in the Venetian Cat Views on Venice blog. Perhaps you might want to have a look at that blog again so you can get a sense of just how small this town is, not only in space, but in time. In fact, you might want to get yourselves a pencil right now and keep a score card:)

http://viewsonvenice.blogspot.com/

If you've read Andrea's first book, A Venetian Affair, the second, Lucia, about Memmo's daughter, is even better. Andrea began his talk, and his book, Lucia in the Age of Napoleon, wondering why the enormous statue of Napoleon is inside the entrance of Palazzo Mocenigo. And that is everyone's first reaction: what in tarnation is that thing doing there? Then you sort of don't notice it anymore, the way you wouldn't notice a pink elephant if it were always there. Here is Andrea's description:

If you've read Andrea's first book, A Venetian Affair, the second, Lucia, about Memmo's daughter, is even better. Andrea began his talk, and his book, Lucia in the Age of Napoleon, wondering why the enormous statue of Napoleon is inside the entrance of Palazzo Mocenigo. And that is everyone's first reaction: what in tarnation is that thing doing there? Then you sort of don't notice it anymore, the way you wouldn't notice a pink elephant if it were always there. Here is Andrea's description:

The statue, wedged into a corner, faces a damp wall in the androne (water-level entrance) of Palazzo Mocenigo, the venerable old palazzo on the Grand Canal which once belonged to my family. The emperor is clad in a Roman toga. His left arm is extended forward, as if he were pointing to a luminous future, though in fact he stares vacuously at the peeling wall in front of him. A mantle of dark grey soot has settled on to his shoulders, and a slab of roughly hewn marble links the raised arm to the head, giving the statue an unfinished look. It is hard to imagine a more incongruous presence than the one of a youthful Napoleon standing sentinel in that humid hallway to the sound of brackish water slapping and sloshing in the nearby canal.

Back in 2001, when I was writing for the IHT-Italy Daily, I saw the statue for the first time. I had just submitted a piece about Vivaldi, and was on vacation in Croatia, splashing sweetly in the sea by Rovinj, when my editor in Milano called. He said my editor in NYC was not happy with the piece, and could I please rewrite it? Vivaldi was too old, too dusty; he wanted something more contemporary. "Oh, sure. No problem," I said, and tossed my cell phone to a baby shark.

Seriously, I think I had two days when I got back to Venice to tweak the piece, and I decided to write about composers in Venice in general (subtitled: The Music of Vivaldi and Many Modern Composers Attest to the Serenissima's Rich Musical Tradition -- and no, I did not write that!). A friend said he knew a Spanish pianist who lived in Lord Byron's former apartment. Enrique Pérez de Guzmàn graciously granted me an interview inside the very rooms you see there. I mixed the story into the previous Vivaldi piece, tossed and served. My slave-driving editor in NYC, Claudio Gatti, was pleased. This is from the IHT-Italy Daily September 7, 2001:

Seriously, I think I had two days when I got back to Venice to tweak the piece, and I decided to write about composers in Venice in general (subtitled: The Music of Vivaldi and Many Modern Composers Attest to the Serenissima's Rich Musical Tradition -- and no, I did not write that!). A friend said he knew a Spanish pianist who lived in Lord Byron's former apartment. Enrique Pérez de Guzmàn graciously granted me an interview inside the very rooms you see there. I mixed the story into the previous Vivaldi piece, tossed and served. My slave-driving editor in NYC, Claudio Gatti, was pleased. This is from the IHT-Italy Daily September 7, 2001:

"I was bitten by Venice," said Pérez de Guzmán. "I fell in love with the city. You establish a rapport -- it gives you a peaceful feeling so that you can create. You absorb all the beauty and peace that Venice gives you, and incorporate it into your own work, then give it back to the world. To create your own music, to find peace of mind in order to create a new repertoire or to get ready for the season, Venice is ideal.For centuries, artists and musicians have come to Venice for inspiration. Wagner composed the second act of 'Tristan und Isolde' here for many of the same reasons, I imagine. Tchaikowsky was here, Mozart, Goethe, Ezra Pound and John Ruskin. Lord Byron wrote the first two cantos of his masterpiece 'Don Juan' right here in these rooms. Benjamin Britten and Arthur Rubinstein have played the piano in my drawing room. Some of the greatest talents in the world have held private concerts in this palazzo."A few years later I had a regatta party at my house -- it could have been for the Vogalonga because I vaguely remember Enrique wearing something stripey inspired by that theme. Pierre Higonnet, who then owned the Galleria del Leone over on Giudecca, brought Andrea di Robilant as his guest. And that, folks, is how Andrea met Enrique, who was living in Lord Byron's apartment inside Palazzo Mocenigo, and that is how I met Andrea.

Andrea writes about Lucia Mocenigo's most famous tenant, Lord Byron:

Lucia and Byron parted on very unfriendly terms, yet in a way the poet never really left Palazzo Mocenigo, or Venice for that matter, and still today his spirit hovers over the city he helped to resurrect. Venice was dead when he arrived in 1816, and the Austrians had no intention of spending money or effort to revive it... It was Byron, a stranger to Lucia's Venetian world, who gave the city a new life by turning those sinking ruins into an existential landscape -- an island of the soul...What Lord Byron wrote upon exiting Palazzo Mocenigo:

I have replenished three times over and made good by the equivalent of the doors and canal posts any little damage to her pottery. If any articles were taken by mistake, they shall be restored or replaced; but I will submit to no exorbitant charge nor imposition. What she may do I neither know nor care; if they like the law they shall have it for years to come, and if they gain, what then? They will find it difficult to 'shear the wolf' no longer in Venice. They are a damned, infamous set... a nest of whores and scoundrels.Even today, palaces and artistocracy hold a great fascination for travelers to Venice, as does the Age of Napoleon. During Carnival, guests plop down hundreds -- if not thousands -- of euro to dress up as aristocrats and reinact the balls, a curious phenomenon to American eyes, since it is not part of our system. Gilbert von Studnitz, a German nobleman, begins his precise explanation of European aristocracy with this sentence:

The German system of nobility, as indeed the European system in general, is quite different from the English system with which most Americans are familiar.http://www.worldroots.com/brigitte/royal/germannobility.htm

I will confess as to being completely confused myself, since there seems to be all sorts of creatures running around Venice with titles at any given moment, behaving in the strangest fashion. This is where Lucia in the Age of Napoleon comes in handy. Not only was Lucia a Memmo herself, descended from one of the oldest families in Venice, she had married a Mocenigo, a family who had produced a whopping seven Doges for the Venetian Republic, plus she had lived through the Venetian Republic's collapse, through Napoleon, through the Austrian Empire -- all the way through to Lord Byron -- and she kept notes! For example, after she became lady-in-waiting to Empress Josephine's daughter-in-law, Princess Augusta, this is what she wrote in a letter to her sister, Paolina:

I lead the dullest existence, rushing from my apartment to Court and from Court to my apartment. What does one do at Court? Well, the evenings in which we have Grand cercel (Large Circle) we tend to sit around for about an hour before moving to the gaming room. When the card-playing is over the Princess rises, says a few nice words to us and I run back home as fast as I can. When we have Petit cercle ( Small Circle) only those attached to the Court are invited. The evening usually begins with a session of baby-watching: we crowd around ten-month-old Josephine, Princess of Bologna, as she plays in her pen. Very interesting...

I lead the dullest existence, rushing from my apartment to Court and from Court to my apartment. What does one do at Court? Well, the evenings in which we have Grand cercel (Large Circle) we tend to sit around for about an hour before moving to the gaming room. When the card-playing is over the Princess rises, says a few nice words to us and I run back home as fast as I can. When we have Petit cercle ( Small Circle) only those attached to the Court are invited. The evening usually begins with a session of baby-watching: we crowd around ten-month-old Josephine, Princess of Bologna, as she plays in her pen. Very interesting...

It was educational to read how the family routinely switched loyalties and languages between France and Austria, depending on which was more prudent. Even more enlightening was how intelligent, enterprising and educated Lucia was. In general, Lucia led a lonely existence, since her husband, Alvise, left her alone for long periods of time. She had several miscarriages before they finally produced an heir, a son, Alvisetto, who also died young.

But then, Lucia did something extraordinary -- she fell in love with a dashing, daring Irish-Austrian Colonel with the Hollywood name of Baron Maximilian Plunkett. They began a secret love affair, which produced a secret son! Maximilian died gloriously in a rain of French bullets two days after his son was christened. Lucia's husband, Alvise, didn't find out for four years; of course, he was furious when he did. But, ultimately, he was pragmatic. Being without an heir himself, he decided to change the boy's name (which was Massimiliano) to Alvise, or Alvisetto (I guess we can call him

Alvisetto Due), and turn his wife's lover's son into a Mocenigo. Oh, those wacky aristocrats!

This is from an interview that Andrea did with Robert Murphy for

W Magazine:

Most stunningly, perhaps, di Robilant's book blows the cover off a two-hundred-year-old family secret. While examing archives in Venice, he discovered that Lucia's only son to survive infancy, theretofore presumed legitimate, was actually the fruit of an illicit union with an alluring Irish-Austrian officer. "For a long while I wondered why my father had red sideburns," said di Robilant. "Everything that brings out the truth is good. It puts into perspective all this crap about blood and legitimacy. Who would have figured that I was part Irish?"

Most stunningly, perhaps, di Robilant's book blows the cover off a two-hundred-year-old family secret. While examing archives in Venice, he discovered that Lucia's only son to survive infancy, theretofore presumed legitimate, was actually the fruit of an illicit union with an alluring Irish-Austrian officer. "For a long while I wondered why my father had red sideburns," said di Robilant. "Everything that brings out the truth is good. It puts into perspective all this crap about blood and legitimacy. Who would have figured that I was part Irish?"(That gorgeous image you see of Andrea di Robilant was taken by Pamela Berry http://www.studiopb.com/.)

Ciao from Venice,

Cat

Venetian Cat - Venice Blog

How many children now read printed poetry for pleasure? Did they ever? Or is it just one of those things that has to be got through at school and then forgotten forever? I don’t think so. Poetry is part of all our lives. We start off as babies being sung to—not all of us, but most. Lullabies, nursery rhymes—all poetry. All of us can remember some of those, and we probably pass them on to our own children. They are part of the fabric of our family lives. But what happens later on? Certainly there are many excellent teachers who inspire and encourage children to write poetry, and it is taught to GCSE and A level (though the curriculum collections are not terribly exciting according to my son). However, most children I talk to find conventional written poetry totally irrelevant to their daily existence, even though they’ll listen to songs (poetry and music) all day on their i-pods—and maybe even learn the lyrics. They would read a book for pleasure—but a book of poetry? Forget it! That’s, like, homework or something. As a poet myself, writing for both children and adults, I find this deeply discouraging, and yet I will not stop writing poetry because of it.

For me, writing a poem is the most sublime of literary experiences in miniature. Every word—where it goes, what it is next to—every comma and full stop and colon or the lack of them, matters to me, whether it is ‘fun’ poetry such as limericks and modern nursery rhymes, or something more serious and deep. But—and this is important—what matters to me as a poet is not necessarily what matters to my readers. When I was doing my MA at Edinburgh, we did something called ‘deconstruction’ as a form of literary criticism. This was supposed somehow to give students an insight into the mind of the poet and his or her meaning. Deconstructing John Donne ruined his poems for me for years (and I think that Jacques Derrida, the inventor of deconstruction, should be consigned to Purgatory, but that is another discussion!). In my opinion (and please feel free to disagree), the essence of a poem will be experienced differently by each and every reader. However the one thing that will be held in common if it is a good poem is that the heart or mind have been touched by some sort of recognition, some sort of ‘oh yes—I have felt/seen/done (or whatever) that’ moment. My own adult poetry writing is triggered by all sorts of things—a walk, emotions high and low, a heard word, the colour of grass, the lines on my mother’s hand to name but a few. I write it for me, because I simply have to get that particular part of me down on paper. I fiddle and wrestle and reformat and layer meanings one on the other until I feel it is perfect of its kind—whether triolet or sonnet or free form. I no longer have to make it rhyme—though I do sometimes. What matters is the baring of my soul, and very often these poems are private and never shown to anyone. They don’t necessarily need any audience except me. My children’s poetry is different. That’s what I have fun with, play with, and hopefully sell. But it’s just as important to me to get it as perfect as I can. This applies to all my writing of course—but because a poem is shorter by its nature, every word is weighed and balanced, every syllable must count or out it goes.

In my own small way I do my best to get a very ancient form of poetry over to the next generation with my

bardic poetry workshops—and I am eternally delighted with the incredible creativity shown by the many children I work with in schools. I know that Michael Rosen, Benjamin Zephaniah and a myriad other poets both sung and unsung do a fantastic job on the road, and that poetry is manifested in many other ways—listen to rap lyrics for some very good modern examples of ‘non-conventional’ poetry. But I do despair that our children are not reading, discovering and enjoying some of the older stuff—or even the more modern—for themselves outside school. I don’t want to sound like a Grumpy Old Writer (though I fear I do), but I’d love it if the next book of poetry published could cause as much noise, gossip and fanfare and receive as much coverage as

Byron’s ‘Don Juan’ did when it appeared in 1819. It’s ‘a thousand pities’ that it probably won’t.

![]()

We’ve collected the books debuting on Indiebound’s Indie Bestseller List for the week ending October 12, 2014–a sneak peek at the books everybody will be talking about next month.

We’ve collected the books debuting on Indiebound’s Indie Bestseller List for the week ending October 12, 2014–a sneak peek at the books everybody will be talking about next month.

(Venice, Italy) I nominate Andrea di Robilant for American Ambassador to Italy, or Italian Ambassador to the United States, whichever position becomes available first. He is an international treasure and should be paid a pot of gold and a rainbow to bridge the gap between the cultures. Son of an American mother and an Italian father, Andrea's ancestors also include two of the most ancient noble families in Venice, the Memmos and the Mocenigos. Most importantly, he has a tri-cultural sense of humor.

(Venice, Italy) I nominate Andrea di Robilant for American Ambassador to Italy, or Italian Ambassador to the United States, whichever position becomes available first. He is an international treasure and should be paid a pot of gold and a rainbow to bridge the gap between the cultures. Son of an American mother and an Italian father, Andrea's ancestors also include two of the most ancient noble families in Venice, the Memmos and the Mocenigos. Most importantly, he has a tri-cultural sense of humor.

Brilliant post, Clauds. Hugely important to get right and ever changing. It’s amazing what was “acceptable” when I was a kid. Kids aren’t as naive these days.

In this info age, writers can’t afford to make sweeping statements unless it’s a matter of opinion. Opinion has its place as well. It’s a matter of reporting.