It never ceases to amaze me that every so often you come across a cultural product (in this case, a writer) you’ve never heard of, but that’s (who’s) immensely popular and bestselling in another country. Tommy Wieringa is an award-winning Dutch writer. He’s published many books to critical and award claim, and the book most […]

Add a CommentViewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: booker prize, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 8 of 8

Blog: Perpetually Adolescent (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Tommy Wieringa, Libris Prize, fiction, booker prize, Book Reviews - Fiction, Fiona Crawford, Add a tag

Blog: Galley Cat (Mediabistro) (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Awards, Tom McCarthy, Booker Prize, Man Booker International Prize, Add a tag

Last week the UK gambling site Ladbrokes stopped taking bets on the Man Booker Prize (to be announced Oct. 12) when shortlisted novelist Tom McCarthy‘s C suddenly earned £15,000 of bets in a single day–as if the gambling world knew something the literary world didn’t

According to the Guardian, Ladbrokes spokesperson David Williams was befuddled by this rush of bets McCarthy’s novel. The book tells the story of a troubled young genius during the early years of the 20th Century. While gamblers furiously chased odds last week for the Nobel Prize in Literature, Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa defied the odds to win.

Williams had this statement: “This year there wasn’t really a standout name among the six shortlisted candidates, no Rushdie or Banville, so you’d expect to see a good spread of business, with a few people having a £10 bet on him or her … [then] every single bet started striking on one man. It wouldn’t be so surprising if there were a Rushdie in the race, but with respect, in this case it was borderline inexplicable and we decided to pull the plug.”

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

Add a CommentBlog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Prose, OWC, tennyson, booker prize, oxford world's classics, adam foulds, adam roberts, the quickening maze, Poetry, Literature, UK, A-Featured, Add a tag

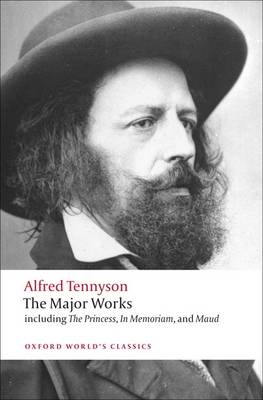

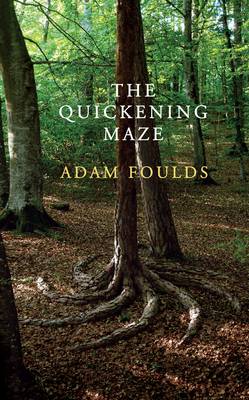

Adam Roberts is Professor of Nineteenth-Century Literature at Royal Holloway, University of London, as well as a science fiction novelist. He is the editor of Tennyson: the Major Works, which was recently published in the Oxford World’s Classics series. In the original post below, he reviews the Booker shortlisted novel The Quickening Maze, by Adam Foulds, which features Tennyson as a main character.

If you’d like to read more by Adam Roberts, he also writes for literary blog, The Valve.

I picked up Adam Foulds’ excellent new novel The Quickening Maze (it has, as I’m sure you know, been shortlisted for this year’s Booker Prize) with more than an ordinary reader’s interest. You see, this scrupulously researched historical novel takes Alfred Tennyson as one of the main characters; and I, as the editor of Tennyson: the Major Works, was curious as to how Foulds treats him.

I was not disappointed. The Quickening Maze is, throughout, a beautifully written fiction: set in 1840 and centred on the lunatic asylum run by Dr Matthew Allen on the outskirts of Epping Forest, the novel evokes its world with a poet’s eye and skill at phrasing—indeed the book is as much about poetry, or poetic perception, as it is about a series of events. The point-of-view shifts deftly between all the main characters, including a number of the inmates at the asylum; although the peasant poet, John Clare, is the main focus. A patient in Allen’s asylum, his sanity is precarious at the beginning of the tale and becomes less stable as it goes on. Fould’s vivid, precise way with poetic image, and his exquisite control of language, brilliantly evoke the world through Clare’s hyper-sensitive eyes.

I was not disappointed. The Quickening Maze is, throughout, a beautifully written fiction: set in 1840 and centred on the lunatic asylum run by Dr Matthew Allen on the outskirts of Epping Forest, the novel evokes its world with a poet’s eye and skill at phrasing—indeed the book is as much about poetry, or poetic perception, as it is about a series of events. The point-of-view shifts deftly between all the main characters, including a number of the inmates at the asylum; although the peasant poet, John Clare, is the main focus. A patient in Allen’s asylum, his sanity is precarious at the beginning of the tale and becomes less stable as it goes on. Fould’s vivid, precise way with poetic image, and his exquisite control of language, brilliantly evoke the world through Clare’s hyper-sensitive eyes.

But Tennyson has a large part to play too. He comes into the story as he oversees the admittance of his brother Septimus (suffering from the melancholic ‘black blood’ of the Tennysons) to the asylum, living there for nearly three years. Dr Allen befriends Tennyson, and persuades him to invest in his idea for an automated wood-lathe—in fact Tennyson put almost all the money he had, £3000, into this scheme, only to lose it all. The doctor’s pale, bookish daughter Hannah falls hopelessly in love with Tennyson, although the emotion is not reciprocated.

Foulds has certainly done his research. He credits Robert Bernard Martin’s dependable biography Tennyson: the Unquiet Heart in his acknowledgments, but I take this to be modest understatement on his part; because one thing that emerges from this book is how well Foulds knows his pre-1840s Tennyson. I’ll give a few examples. Early in the book Tennyson talks philosophy with Allen, who believes in a ‘Grand Agent’ behind the phenomena of reality: ‘a common cause, a unitary force.’ Tennyson concurs.

“I see. A Spinozism, of sorts.” And Tennyson did see: a white fabric, candescent, pure, flowing through itself, surging,  charged, unlimited. And in the world the flourishing of forms, their convulsions: upward thrive of trees, sea waves, the mathematical toy of sea shells, the flight of dragonflies. [25]

charged, unlimited. And in the world the flourishing of forms, their convulsions: upward thrive of trees, sea waves, the mathematical toy of sea shells, the flight of dragonflies. [25]

This is nicely done; and if the reader of Tennyson recognises the sea-shell from Maud, the dragonfly from ‘The Two Voices’ it only contributes to the effect. Fould’s Tennyson goes on more specifically:

“As a boy I could put myself into a trance by repeating my name over and over until my sense of identity was quite dissolved. What I was then was a being somehow merging, or sustained, with a greater thing, truly vast. It was abstract, warm, featureless and frightful.” [The Quickening Maze, p.26]

This speech has been lifted from a letter Tennyson wrote (late in his life—in 1874) to an American mystic and writer Benjamin Paul Flood. Flood, it seems, believed it was possible to enter a spiritual trance state via the newly discovered medical technologies of anasthesia. Tennyson wrote:

I have never had any revelations through anaesthetics: but “ a kind of waking trance” (this for lack of a better word) I have frequently had quite up from boyhood. When I have been all alone. This has often come upon me through repeating my own name to myself silently, till all at once as it were out of the intensity of the consciousness of individuality the individuality itself seemed to dissolve and fade away into boundless being—and this not a confused state but the clearest of the clearest, the surest of the surest, utterly beyond words—where Death was an almost laughable impossibility—the loss of personality (if so it were) seeming no extinction but the only true life. [Tennyson: the Major Works, p.520]

What interests me here is how Foulds have adapted this famous self-description for the purposes of his novel: Tennyson’s actual 1874 account is surprisingly reassuring about this strange fugue state, and wholly positive: ‘not a confused state but the clearest of the clearest … Death was an almost laughable impossibility … no extinction but the only true life’. In the novel, though, it becomes something rather more unnerving: ‘abstract, featureless and frightful’—because The Quickening Maze’s main focus is on madness, on that breakdown of coherent consciousness and its fearful consequences.

‘May I ask you, what is your opinion of Lord Byron’s poetry?’ Hannah, the doctor’s daughter enquires later on in the narrative Tennyson replies:

I remember when he died. I was a lad. I walked out into the woods full of distress at the news. It was the thought of all he hadn’t written, all bright inside him, being lost for ever, lowered into the darkness for eternity. I was most gloomy and despondent. I scratched his name onto a rock, a sandstone rock. It must still be there, I should think. [The Quickening Maze, pp.102-3]

The original for this is a conversation Tennyson had late in life with his son, Hallam.

We talked of Byron and Wordsworth. “Of course,” said Tennyson, “Byron’s merits are all on the surface. This is not the case with Wordsworth. You must love Wordsworth ere he will seem worthy of your love. As a boy I was an enormous admirer of Byron, so much so that I got a surfeit of him, and now I cannot read him as I should like to do. I was fourteen when I heard of his death. It seemed an awful calamity; I remember I rushed out of doors, sat down by myself, shouted aloud, and wrote on the sandstone: “Byron is dead!” [Tennyson: the Major Works, p.541]

Once again Foulds has done something interesting with his source material. The substance of the recollection is the same, but where Tennyson’s original account is a cathartic outpouring—he ‘rushed out of doors’ at the news, ‘shouted aloud’ and wrote on rock to express himself—Foulds internalises the grief. His Tennyson is filled, even glutted, with a grief that is inside: he goes ‘into the woods’; he is ‘full of distress’ at ‘the thought of all he hadn’t written, all bright inside him.’ This interiorisation of experience is one of the main thrusts of the novel. Foulds’ characters all inhabit their subjectivities much more than they live in the world, some to the point of monomaniac madness. The exception also proves the rule: Clare, whose perceptions of the natural world around him furnish the novel with some of its most beautiful moments, cannot escape his own imprisoning imagination. He sinks into a grief-filled interiority—even believing himself to be Lord Byron himself—for he has been unable to cope with the death of his childhood sweetheart Mary, and the fantasy of her being alive again overwhelms him.

The parallels with Tennyson are unobtrusively drawn: in 1840 he was also sunk in grief, at the premature death (in 1833) of his friend Arthur Henry Hallam. Foulds’ Tennyson reverts to memories of Hallam time and again, and across the course of the novel he is writing the elegiac lyrics that were later collected into Tennyson’s most famous poem, ‘In Memoriam A. H. H.’ Foulds quotes the ninth:

Fair ship, that from the Italian shore

Sailest the placid ocean-plains

With my lost Arthur’s loved remains,

Spread thy full wings, and waft him o’er.

So draw him home to those that mourn

In vain; a favourable speed

Ruffle thy mirror’d mast, and lead

Thro’ prosperous floods his holy urn.

All night no ruder air perplex

Thy sliding keel, till Phosphor, bright

As our pure love, thro’ early light

Shall glimmer on the dewy decks.

Sphere all your lights around, above;

Sleep, gentle heavens, before the prow;

Sleep, gentle winds, as he sleeps now,

My Friend, the brother of my love;

My Arthur, whom I shall not see

Till all my widow’d race be run;

Dear as the mother to the son,

More than my brothers are to me. [The Quickening Maze, pp. 107-8; Tennyson: the Major Works, p.209]

That Tennyson is sane, and Clare mad, has as much to do with the different emphases of their imaginative engagements with mourning. Tennyson styles himself, patiently, as Arthur’s ‘widow’, in the last stanza there; a feminisation that Foulds develops in his fictional recreation of the poet’s personality. Clare, on the other hand, chafes against his restrains. He believes himself a famous pugilist, and fights with the asylum’s warders and with local gypsies. He roams restlessly through Epping forest, and—in a superb passage at he novel’s end—walks all the way back to his home village, a journey of 80 miles or more, overcoming the obstacles placed in his way, landscape, hunger and weakness. By comparison Tennyson moves smoothly: Foulds captures well his stillness and inwardness, his silences, the way he draws things into himself—not least, tobacco smoke (Allen “watched Tennyson relight his pipe, hollowing his clean-shaven cheeks as he plucked the flame upside down into the bowl of scorched tobacco’ [23]”). In all, it’s very deftly and sensitively done. The novel is highly recommended.

Blog: An Awfully Big Blog Adventure (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Ann Turnbull, Mary Hoffman, Booker Prize, Leslie Wilson, English civil war, Albigensian crusade, apologies to my brother, Add a tag

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: george orwell, UK, Blogs, edinburgh, A-Featured, link love, john hughes, stephen fry, booker prize, Add a tag

Greetings from Oxford, where we are currently between downpours of rain, though I’m assured that it is still officially summer. Who knew? Anyway, here’s my pick of the web this week.

The Guardian asks what’s the best TV show of the 2000s? Frontrunner so far seems to be The Wire (although I voted for The West Wing).

With the Edinburgh Fringe kicking off this week, here’s a list of the 10 strangest festival venues.

Mary Beard on what computers do to handwriting.

The longlist of 2009’s Man Booker Prize for Fiction has been announced.

Stephen Fry on America’s place in the world.

Apparently there might have been cannibals in England 9000 years ago.

How Orwellian was George Orwell?

Farewell John Hughes, who has died at the age of 59. The Guardian looks at his career in clips.

The secret royals: illegitimate children of British monarchs.

Blog: Bookfinder.com Journal (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Bookish, Booker Prize, betting, longlist, Add a tag

Having just gotten back to the office after a week away I'm catching up on my news, so my apologies if this is old hat for you.

When the Booker Prize long list was announced the other week the usual guessing on who would win started to take place. The bookmakers all posted their odds and the punters began dropping their bets like usual. However, as the Telegraph reported last week, betting patterns have been anything but ordinary with 95% of all bets being placed on Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall.

"It's almost like an unspoken psychic rumour has gone round that this will be Hilary Mantel's year," spokesman Graham Sharpe said, as the odds were cut from 12/1 to make it the clear 2/1 favourite.

"We'll lose a five figure sum if the support continues. It is as though a tip has gone around the literary world telling everyone that Mantel is a certainty.

In the last couple years the odds on favorite has not won, however there has not been this level of interest in Booker Betting since 2002 when Yan Martel's Life of Pi was bet on as if it were a shoe in.

"Quite a lot of them (people placing the bets) are what we would describe as literary insiders," he said.

"Nobody quite seems to know why."

But he ruled out the notion of any foul play, saying: "It would be unusual for the judges to know who they were picking as the eventual winner already. I would be very, very surprised if the judges had already decided.

"It's not in the realms of crying foul or anything like that, it may be just a case of a lot of people deciding on the same one at the same time."

He added it was "very, very rare to

see this type of gamble" and said it was "definitely the biggest Booker gamble

since Life of Pi was backed as though defeat was out of the question a few years

ago".

William Hill's latest 2009 Man Booker Prize for Fiction odds are:

:: 2/1 Hilary Mantel - Wolf Hall;

:: 4/1 Colm Toibin - Brooklyn;

:: 4/1 Sarah Waters - The Little Stranger;

:: 6/1 JM Coetzee - Summertime;

:: 6/1 James Lever - Me Cheeta;

:: 10/1 AS Byatt - The Children's Book;

:: 12/1 William Trevor - Love and Summer;

:: 14/1 Ed O'Loughlin - Not Untrue & Not Unkind;

:: 14/1 Simon Mawer - The Glass Room;

:: 16/1 Adam Foulds - The Quickening Maze,

:: 16/1 Sarah Hall - How to Paint a Dead Man,

:: 16/1 Samantha Harvey - The Wilderness;

:: 16/1 James Scudamore - Heliopolis.

I'm not a betting man but if I were I would put my money down on AS Byatt, I think she's the dark horse in this race (it should be known I have failed to call every booker I have atempted). How about the rest of you Journal readers, who do you think will win this years Booker?

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: public domain, Blogs, Current Events, A-Featured, NASA, booker prize, AIG, Hubble, Add a tag

by Cassie, Publicity Assistant

Happy Friday everyone! We’re sneaking out a bit early to go bowling today, aren’t you jealous? The week will end with beer and bowling balls, which is about as much as you can ask for in a week. I go on vacation next Thursday, so you all will be without me for a little while. Can you pretend to notice so I feel better? Thanks! In the meantime, here are some links to keep you occupied until you sneak out for your own bowling match.

All of us here at OUP send our condolences to Natasha Richardson’s family and friends. There are many touching articles out there about this week’s tragedy, take some time to check some out.

The geek in me really wants one of these, but the practical person tells me it’s probably not very comfortable.

The long lists for the Booker and the Orange prizes have been announced.

I had no idea eavesdropping was so complicated!

It’s a start, at least…some at AIG are paying back their bonuses.

Remember when I posted a link about voting for the next celestial body Hubble studies? (Didn’t I do that? Or was it naming the ISS?) Here’s the winner!

Spacebat, we hardly knew thee.

When Fifth graders have anger management issues.

Sony Reader now offering 500,000 public domain titles.

Put a red bulb in this and you have Sauron’s eye staring at you. Good thing it’s just a concept design!

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: UK, Blogs, A-Featured, bethlem, booker prize, giles coren, joanna lumley, Add a tag

Hello, Kirsty from OUP UK here. It’s my turn to share with you fine people the cream of the internet crop. Or at least, what I’ve been reading this week. It’s starting to get warm here in Oxford, so I’m planning to have a BBQ tonight. Hope you all have similarly sunny weekends.

Awww! Nothing like a blogular love story to warm even the hardest hearts.

The Booker Prize longlist has been announced this week. A few surprises on the list, and no less than five first time novelists. And Salman Rushdie.

I’m a 19th century geek, so this week I have been completely fascinated with this guide to Bethlem Royal Hospital in Victorian times. Bethlem was the psychiatric hospital which gave us the word ‘bedlam’, after the hospital’s nickname.

Joanna Lumley, one of the stars of Absolutely Fabulous and The Avengers, has made some controversial remarks about modern poetry.

This is one of my favourite news stories of the week: a New Zealand girl was made a ward of court so that she could change her name. Her parents had named her - wait for it - Talula Does The Hula In Hawaii. Poor kid.

The UK blogs and newspaper columns were this week alive with a leaked email from restaurant critic Giles Coren to the sub-editors at The Times. They had removed an ‘a’ from his copy. He was not amused. (NB. the email contains VERY strong language. Don’t say I didn’t warn you).

Is it just me that is suddenly obsessed with cataloguing their books online with LibraryThing? Who knew that entering a list of every book you own could be such fun. Turns out I have around 1,160 books in my house (not counting the box in the attic I haven’t got round to yet).

Hi,

I found you from Nicola's coffee morning! Thought I would stop in, say hello and be very relieved that you didn't eat the "liquorice"

Kate x

Thanks for great reviews Leslie... (you need to put your name up with your title to use the web to your advantage... otherwise no one knows it's you!)Good to have some historical books. I'm looking forward to reading Wolf Hall. Just bought it(great endpapers)and also The Glass Room.

Thanks, Di, I've done that now!

Leslie