new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Gravity, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 13 of 13

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Gravity in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Jerry Beck,

on 12/1/2016

Blog:

Cartoon Brew

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Interviews,

Avatar,

Tech,

CGI,

Gravity,

The Matrix,

Digital Domain,

SIGGRAPH,

Sony Pictures Imageworks,

VR,

VFX,

Industrial Light & Magic,

Framestore,

Weta Digital,

Paul Debevec,

Furious 7,

photogrammetry,

SIGGRAPH Asia,

Google Daydream,

Spider-Man 2,

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button,

Add a tag

A deep dive with researcher Paul Debevec, who has been pivotal in some of the biggest innovations in vfx, including photoreal digital characters.

The post Paul Debevec: A Name You Absolutely Need to Know in CG, VFX, Animation, and VR appeared first on Cartoon Brew.

By: Jerry Beck,

on 11/3/2016

Blog:

Cartoon Brew

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Business,

VFX,

Gravity,

The Golden Compass,

Paddington,

Beauty and the Beast,

Guardians of the Galaxy,

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them,

Framestore,

Doctor Strange,

William Sargent,

Add a tag

"I'm looking east," says the founder and CEO of Framestore.

The post ‘Gravity,’ ‘Dr. Strange’ VFX Studio Framestore Bought by Chinese Firm appeared first on Cartoon Brew.

By: Franca Driessen,

on 10/8/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

gravity,

NASA,

astronomy,

international space station,

outer space,

astronauts,

ISS,

final frontier,

Oxford Reference,

space travel,

G-force,

aerospace,

Lisa Brown,

*Featured,

Physics & Chemistry,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

Online products,

World Space Week,

space flight,

Earth & Life Sciences,

Space Research,

Advanced Resistive Exercise Device,

aerospace medicine,

ARED,

microgravity,

Shuttle Atlantis,

Add a tag

World Space Week has been celebrated for the last 17 years, with events taking place all over the world, making it one of the biggest public events in the world. Highlighting the research conducted and achievements reached, milestones are celebrated in this week. The focus isn’t solely on finding the ‘Final Frontier’ but also on how the research conducted can be used to help humans living on Earth.

The post Space travel to improve health on earth appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Amy Jelf,

on 2/22/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

einstein,

space,

gravity,

theory of relativity,

VSI,

Very Short Introductions,

outer space,

black holes,

stephen blundell,

A Very Short Introduction,

*Featured,

Physics & Chemistry,

Science & Medicine,

General Relativity,

black holes VSI,

Gravitational Waves,

Katherine Blundell,

Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory,

LIGO,

theory of General Relativity,

Add a tag

The discovery of gravitational waves, announced on 11 February 2016 by scientists from the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO), has made headline news around the world. One UK broadsheet devoted its entire front page to a image of a simulation of two orbiting black holes on which they superimposed the headline "The theory of relativity proved".

The post When black holes collide appeared first on OUPblog.

By: DanP,

on 7/6/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

myths,

apple,

alchemy,

bible,

gravity,

British,

physics,

isaac newton,

newton,

trinity college,

*Featured,

Physics & Chemistry,

Science & Medicine,

newton’s,

gravitational pull,

sarah dry,

The Newton Papers,

Add a tag

By Sarah Dry

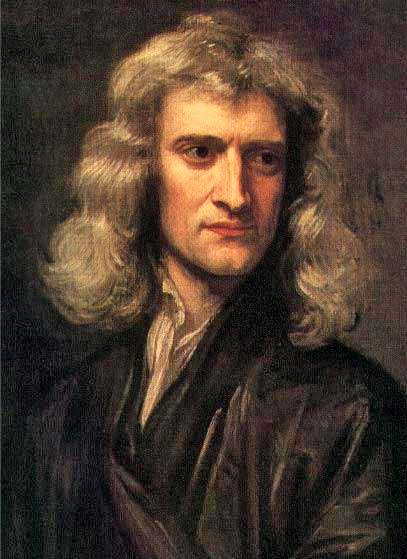

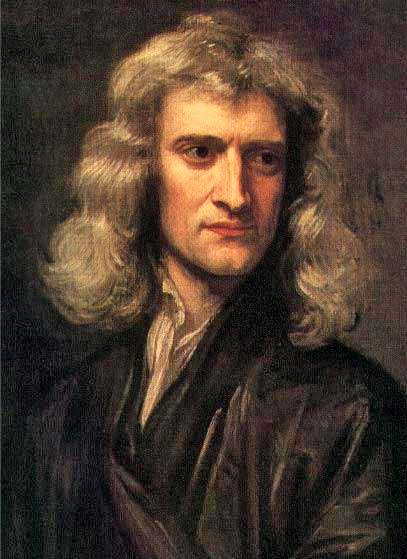

Nearly three hundred years since his death, Isaac Newton is as much a myth as a man. The mythical Newton abounds in contradictions; he is a semi-divine genius and a mad alchemist, a somber and solitary thinker and a passionate religious heretic. Myths usually have an element of truth to them but how many Newtonian varieties are true? Here are ten of the most common, debunked or confirmed by the evidence of his own private papers, kept hidden for centuries and now freely available online.

10. Newton was a heretic who had to keep his religious beliefs secret.

True. While Newton regularly attended chapel, he abstained from taking holy orders at Trinity College. No official excuse survives, but numerous theological treatises he left make perfectly clear why he refused to become an ordained clergyman, as College fellows were normally obliged to do. Newton believed that the doctrine of the Trinity, in which the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost were given equal status, was the result of centuries of corruption of the original Christian message and therefore false. Trinity College’s most famous fellow was, in fact, an anti-Trinitarian.

9. Newton never laughed.

False, but only just. There are only two specific instances that we know of when the great man laughed. One was when a friend to whom he had lent a volume of Euclid’s Elements asked what the point of it was, ‘upon which Sir Isaac was very merry.’ (The point being that if you have to ask what the point of Euclid is, you have already missed it.) So far, so moderately funny. The second time Newton laughed was during a conversation about his theory that comets inevitably crash into the stars around which they orbit. Newton noted that this applied not just to other stars but to the Sun as well and laughed while remarking to his interlocutor John Conduitt ‘that concerns us more.’

8. Newton was an alchemist.

True. Alchemical manuscripts make up roughly one tenth of the ten million words of private writing that Newton left on his death. This archive contains very few original treatises by Newton himself, but what does remain tells us in minute detail how he assessed the credibility of mysterious authors and their work. Most are copies of other people’s writings, along with recipes, a long alchemical index and laboratory notebooks. This material puzzled and disappointed many who encountered it, such as biographer David Brewster, who lamented ‘how a mind of such power, and so nobly occupied with the abstractions of geometry, and the study of the material world, could stoop to be even the copyist of the most contemptible alchemical work, the obvious production of a fool and a knave.’ While Brewster tried to sweep Newton’s alchemy under the rug, John Maynard Keynes made a splash when he wrote provocatively that Newton was the ‘last of the magicians’ rather than the ‘first king of reason.’

7. Newton believed that life on earth (and most likely on other planets in the universe) was sustained by dust and other vital particles from the tails of comets.

True. In Book 3 of the Principia, Newton wrote extensively how the rarefied vapour in comet’s tails was eventually drawn to earth by gravity, where it was required for the ‘conservation of the sea, and fluids of the planets’ and was most likely responsible for the ‘spirit’ which makes up the ‘most subtle and useful part of our air, and so much required to sustain the life of all things with us.’

6. Newton was a self-taught genius who made his pivotal discoveries in mathematics, physics and optics alone in his childhood home of Woolsthorpe while waiting out the plague years of 1665-7.

False, though this is a tricky one. One of the main treasures that scholars have sought in Newton’s papers is evidence for his scientific genius and for the method he used to make his discoveries. It is true that Newton’s intellectual achievement dwarfed that of his contemporaries. It is also true that as a 23 year-old, Newton made stunning progress on the calculus, and on his theories of gravity and light while on a plague-induced hiatus from his undergraduate studies at Trinity College. Evidence for these discoveries exists in notebooks which he saved for the rest of his life. However, notebooks kept at roughly the same time, both during his student days and his so called annus mirabilis, also demonstrate that Newton read and took careful notes on the work of leading mathematicians and natural philosophers, and that many of his signature discoveries owe much to them.

5. Newton found secret numerological codes in the Bible.

True. Like his fellow analysts of scripture, Newton believed there were important meanings attached to the numbers found there. In one theological treatise, Newton argues that the Pope is the anti-Christ based in part on the appearance in Scripture of the number of the name of the beast, 666. In another, he expounds on the meaning of the number 7, which figures prominently in the numbers of trumpets, vials and thunders found in Revelation.

4. Newton had terrible handwriting, like all geniuses.

False. Newton’s handwriting is usually clear and easy to read. It did change somewhat throughout his life. His youthful handwriting is slightly more angular, while in his old age, he wrote in a more open and rounded hand. More challenging than deciphering his handwriting is making sense of Newton’s heavily worked-over drafts, which are crowded with deletions and additions. He also left plenty of very neat drafts, especially of his work on church history and doctrine, which some considered to be suspiciously clean, evidence, said his 19th century cataloguers, of Newton’s having fallen in love with his own hand-writing.

3. Newton believed the earth was created in seven days.

True. Newton believed that the Earth was created in seven days, but he assumed that the duration of one revolution of the planet at the beginning of time was much slower than it is today.

2. Newton discovered universal gravitation after seeing an apple fall from a tree.

False, though Newton himself was partly responsible for this myth. Seeking to shore up his legacy at the end of his life, Newton told several people, including Voltaire and his friend William Stukeley, the story of how he had observed an apple falling from a tree while waiting out the plague in Woolsthorpe between 1665-7. (He never said it hit him on the head.) At that time Newton was struck by two key ideas—that apples fall straight to the center of the earth with no deviation and that the attractive power of the earth extends beyond the upper atmosphere. As important as they are, these insights were not sufficient to get Newton to universal gravitation. That final, stunning leap came some twenty years later, in 1685, after Edmund Halley asked Newton if he could calculate the forces responsible for an elliptical planetary orbit.

1. Newton was a virgin.

Almost certainly true. One bit of evidence comes via Voltaire, who heard it from Newton’s physician Richard Mead and wrote it up in his Letters on England, noting that unlike Descartes, Newton was ‘never sensible to any passion, was not subject to the common frailties of mankind, nor ever had any commerce with women.’ More substantively, there is Newton’s lifelong status as a self-proclaimed godly bachelor who berated his friend Locke for trying to ‘embroil’ him with women and who wrote passionately about how other godly men struggled to tame their lust.

Sarah Dry is a writer, independent scholar, and a former post-doctoral fellow at the London School of Economics. She is the author of The Newton Papers: The Strange and True Odyssey of Isaac Newton’s Manuscripts. She blogs at sarahdry.wordpress.com and tweets at @SarahDry1.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via

email or

RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via

email or

RSS.

Image credit: Portrait of Isaac Newton by Sir Godfrey Kneller. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post True or false? Ten myths about Isaac Newton appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 3/5/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Vertigo,

oscars 2014,

wolf of wall street,

gravity,

academy awards,

Books,

*Featured,

TV & Film,

academy of motion picture arts and sciences,

Arts & Leisure,

12 Years a Slave,

Citizen Kane,

Add a tag

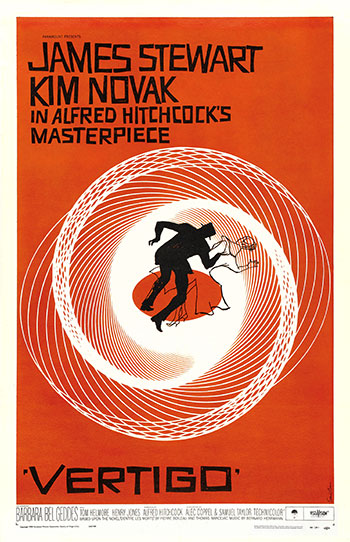

By James Tweedie

The annual Academy Awards ceremony draws weeks of media attention, hours of live television coverage beginning with stars strolling down the red carpet, and around 40 million viewers nationwide on Oscar night. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences relegates the awards for technical achievement to a separate ceremony a couple of weeks before, a sedate affair in a hotel ballroom rather the spectacular setting of the Dolby Theater. While this division between the arts and sciences is clear in awards season, that boundary has almost disappeared in the movies themselves, as computer-generated imagery and digital 3-D now occupy a prominent position in most major studio productions.

Academy Award for Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom at the Walt Disney Family Museum. Photo by Loren Javier. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

For almost a century popular American cinema has been primarily a storytelling medium, with the motion picture sciences playing a more secondary role, but the distinction between the popular arts of Hollywood and the engineering of Silicon Valley is blurring. The movie business is being incorporated into a TED world where technology and design are the cornerstones of most big-budget entertainment.

For the first three hours of Sunday’s broadcast, Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity seemed to be soaring toward a Best Picture Oscar, a victory that would have marked a new stage in this transformation of the American movie industry. A tour de force of technological innovation, Gravity won a total of seven Academy Awards, including the bellwether prizes for Best Editing and Best Director, and the voters appeared on the verge of bestowing their top honor on one of the first films to utilize the full potential of 3-D, a film that creates an almost visceral, stomach-dropping sensation of weightlessness as the camera and bodies appear to bob and drift through space. At other times the camera hurtles forward and the storyline rushes us from one space vehicle to another, propelled by an accidental explosion or the blast of a strategically deployed fire extinguisher. In those moments the weakness of Gravity is as unmistakable as its technical prowess: its virtuoso, gravity-defying feats are accompanied by an almost absurdly insubstantial and implausible plot, even by the standards of Hollywood, where happy endings have been arriving on cue for decades and most cars seem to have a magical sixth gear that allows them to fly over rising drawbridges. The narrative seems almost like an afterthought in Gravity, a pretext to link together one floating space platform and the next and to celebrate cinematic technology in itself, untethering it from earthly concerns like the plot.

But the Academy voters obviously had a different narrative in mind when they submitted their ballots, and in keeping with a long tradition of last-minute plot twists, they managed to compose a far more heartening conclusion to the year in film. In your average year, the Academy Awards are, to borrow the title of one of this year’s Best Picture contenders, an “American hustle.” Every March, we anticipate the canonization of a new Citizen Kane or Vertigo, half-forgetting that these films, among the most revered American movies ever made, won a grand total of one Oscar (Herman Mankiewicz and Orson Welles, for the screenplay for Citizen Kane). Kane was nominated in nine categories and lost eight of them, and Hitchcock and the other makers of Vertigo left the Pantages Theater empty-handed in 1959.

The list of regrettable Academy Award decisions and omissions (for example, Hitchcock’s career-long snub in the Best Director category or the single statuette given to Stanley Kubrick in his lifetime, for visual effects in 2001) is at least as long as Oscar’s triumphs. While viewers tune in for the glitz, glamor, comedy, fashion, and, on occasion, a genuinely moving acceptance speech (or a train wreck taking place at the podium), the ceremony also promises to provide an annual assessment of the state of American cinema. The opulent spectacle arrives each year without fail, but the Academy almost habitually overlooks the truly vibrant pictures and artists working in the film industry in the United States. What does Oscar reward instead?

The recipients of the major awards are usually not the most lucrative blockbusters (which have already received their rewards at the box office) nor are they the type of formally innovative and idiosyncratic pictures that enter the canon retrospectively. The films that tend to be overrated by the Academy are well-meaning films that appear to address an important social issue, while discovering some heroes and reasons for hope in an otherwise trying situation (Slumdog Millionaire, Crash, and Million Dollar Baby, to name three of the last eight Best Picture winners). Films by recognized American auteurs like Martin Scorsese, the Coen brothers, or Kathryn Bigelow have also fared well (see, for example, The Departed in 2006, No Country for Old Men in the following year, and The Hurt Locker in 2009), as have historical films that depict a triumph over hardship, with the formula for contemporary cinema—adversity, heroism, survival, and even a measure of vindication—retooled for use in the past. (See The King’s Speech in 2010 for the most recent example, but note also the run of five consecutive awards beginning in 1993 for Schindler’s List, Forrest Gump, Braveheart, The English Patient, and Titanic, which together established the historical film as a one of the surest paths to the podium.) What matters at Oscar time is the appearance of importance and a willingness to return to historical tragedies or to glance at contemporary social ills.

Viewed in retrospect, the Academy Awards perform something of a bait and switch, as instead of recognizing the best films created in the previous year they provide a barometer of the social and historical problems that continue to haunt us, including (to focus on this year’s nominees) political corruption, the excesses of Wall Street, uneven development, slavery and racism, the AIDS crisis, and the persistence of homophobia. This year’s Best Picture nominees have been justly scrutinized precisely because they seem so intimately linked with the problems they address. Four of the nine nominees are based on actual events drawn from the very recent past, another (Philomena) recounts a true story spanning a 50-year period from the middle of the twentieth century to the present, and 12 Years a Slave retells the autobiography of Solomon Northup, a free African-American from New York who was kidnapped and sold into bondage in Louisiana. Add Gravity to this strong group of films, and oddsmakers were predicting the tightest contest in recent memory, with these many returns to history pitted against an immersive, high-tech cinematic experience of the future.

In The Wolf of Wall Street, Jordan Belfort, a real-life financial scam artist played by Leonardo DiCaprio, finds himself unable to drive home after an overdose of Quaaludes that leaves him prostrate on the front steps of his country club. Summoning all his strength, he manages to slither across the driveway, hoist himself into his gull-winged sports car, and steer through a series of obstacles unscathed. Or at least that’s how the events unfold the first time, in what appears to be Jordan’s experience of reality. Immediately after that sequence, we see the police arrive and Scorsese presents us with a revisionist version, with a wreckage of cars and signposts left flattened in his wake. Hollywood’s approach to the past often resembles the first, more delusional of these scenes, with the heroic figure emerging triumphant from history.

In 12 Years a Slave the historical devastation caused by slavery is more frightening because the damage is all pervasive, because nothing is left uncorrupted by the system that frames every interaction through the lens of property. Screenwriter John Ridley and director McQueen had the courage to let Solomon Northup’s story remain largely unchanged from the original autobiography and to frame the most searing images in the simplest, most direct way, as in the agonizingly long take where a near lynching unfolds almost in slow motion. And in the best tradition of classical Hollywood cinema, McQueen manages to combine a compelling narrative with a series of subtle character portraits, as Northup travels through a looking glass from his prior existence as an accomplished musician and family man in New York to what seems like an alternative universe, where survival depends on the stripping away of those markers of identity and humanity. Rather than present slavery as an incomprehensible evil from another time, the film also chronicles the everyday rationalizations that allow the master to accept depravity as a way of life and the foundation of an economic order.

In most years the Oscars ceremony performs a bait and switch, as we await the announcement of the year’s best films and hear the name of a soon-to-be-forgotten film. But the Academy Awards also remind us why we continue to care about movies and ascribe to them a social significance and power all out of proportion with the relatively modest ambitions of even the Best Picture nominees, let alone the more standard studio fare. The Oscars are an advertisement for the potential of cinema to engage with traumatic historical and contemporary realities, even if we usually have to look elsewhere for the films that address those issues in all of their complexity. 12 Years a Slave, one of the few masterpieces also to win the award for Best Picture, reminds us that sometimes those films can come straight from Hollywood.

James Tweedie is Associate Professor of Comparative Literature and a member of the Cinema Studies faculty at the University of Washington. He is the author of The Age of New Waves: Art Cinema and the Staging of Globalization.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only television and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Steve McQueen’s low-tech triumph: Looking at this year’s Oscar winners appeared first on OUPblog.

No surprise in the Best Animated Feature category. "Frozen" won. No surprise in the Best Visual Effects category. "Gravity " won. Huge surprise in the Best Animated Short category. "Mr. Hublot " won.

By: Taylor Coe,

on 2/28/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Alexandre Desplat,

Kathryn Kalinak,

score,

desplat,

Film Music,

*Featured,

best original score,

TV & Film,

newman,

Arts & Leisure,

book theif,

Owen Pallett,

philomena,

saving mr banks,

Steven Price,

Thomas Newman,

william butler,

pallett,

memorable—vintage,

Books,

Music,

oscars,

gravity,

butler,

very short introduction,

Very Short Introductions,

John Williams,

Add a tag

By Kathryn Kalinak

This year’s slate of contenders includes established pros (John Williams, Thomas Newman, Alexandre Desplat) along with some newcomers (William Butler and Owen Pallett, Steven Price). This used to be a category where you had to pay your dues, but no longer. The last three winners had never been nominated before. So the real surprise winner in this category would be Williams.

William Butler and Owen Pallett: Her

Click here to view the embedded video.

Butler and Pallett already have a pocketful of awards and this is just the kind of “outsider” score (Butler and Pallett’s first nomination) that Academy voters love: remember Reznor and Ross winning for The Social Network? A win for Butler and Pallett makes the Academy seem hip and edgy and cool, not unimportant to an aging votership. Gravity is the favorite to win here, but I wouldn’t be surprised if the statuette goes to Her. Its use of acoustic instruments (that piano!) brings coziness to the sterile interiors and even the electronic instruments radiate warmth. The score is crucial in helping us to understand the characters in the film and feel for them. This wouldn’t be the same film without the score.

Alexandre Desplat: Philomena

Click here to view the embedded video.

Desplat has done some remarkable work in the last few years (Argo, Zero Dark Thirty, The King’s Speech, The Queen, Harry Potter, Fantastic Mr. Fox—a personal favorite) and he’s the go-to composer for films about England and now Ireland. But he’s perennially overlooked by Academy voters (he’s lost five times in the last seven years and for some amazing work—come on, Academy)! I don’t think this is his year. Philomena doesn’t have a high enough profile in the Oscar race. I would LOVE to be wrong about this. Desplat deserves an Oscar for something and why not for Philomena—it’s a heartfelt film with an equally heartfelt score.

Thomas Newman: Saving Mr. Banks

Click here to view the embedded video.

Newman has twelve nominations and no wins but I don’t think this year is going to change that. Saving Mr. Banks was almost completely overlooked by the Academy (this is its only nomination) and Newman’s style of big symphonic scoring hasn’t found favor in recent years with Academy voters. (See John Williams below).

Steven Price: Gravity

*clip from film includes “Debris” from the soundtrack

Click here to view the embedded video.

Gravity is the front runner here. The trailer’s tag line reads “At 372 miles above the earth, there is nothing to carry sound.” Except the soundtrack…which is filled with the score. Big, noticeable, dare I say it—intrusive, this is the kind of score you can’t fail to notice…even if you try. John Williams meets Hans Zimmer.

John Williams: The Book Thief

Click here to view the embedded video.

This is Williams’ forty-ninth nomination—but The Book Thief doesn’t have the visibility of other films in this category and Academy voters of late have failed to embrace the kind of big symphonic scores, like this one, that routinely won Oscars back in the twentieth century. Lush, melodic, memorable—vintage Williams. Like Newman for Saving Mr. Banks, Williams would be an upset.

Will win: Steven Price for Gravity

Should win: William Butler and Owen Pallett for Her

Kathryn Kalinak is Professor of English and Film Studies at Rhode Island College. Her extensive writing on film music includes numerous articles as well as the books Settling the Score: Music in the Classical Hollywood Film and How the West was Sung: Music in the Westerns of John Ford. She is author of Film Music: A Very Short Introduction.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only television and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Best Original Score: Who will win (and who should!) appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/26/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

gravity,

Mathematics,

newton,

*Featured,

Physics & Chemistry,

Émilie du Châtelet,

Science & Medicine,

ether,

Halley,

Mary Somerville,

Clairaut,

Huygens,

Leibniz,

Newtonian Revolution,

Principia,

Seduced by Logic,

newton’s,

Add a tag

By Robyn Arianrhod

This year, 2012, marks the 325th anniversary of the first publication of the legendary Principia (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), the 500-page book in which Sir Isaac Newton presented the world with his theory of gravity. It was the first comprehensive scientific theory in history, and it’s withstood the test of time over the past three centuries.

Unfortunately, this superb legacy is often overshadowed, not just by Einstein’s achievement but also by Newton’s own secret obsession with Biblical prophecies and alchemy. Given these preoccupations, it’s reasonable to wonder if he was quite the modern scientific guru his legend suggests, but personally I’m all for celebrating him as one of the greatest geniuses ever. Although his private obsessions were excessive even for the seventeenth century, he was well aware that in eschewing metaphysical, alchemical, and mystical speculation in his Principia, he was creating a new way of thinking about the fundamental principles underlying the natural world. To paraphrase Newton himself, he changed the emphasis from metaphysics and mechanism to experiment and mathematical analogy. His method has proved astonishingly fruitful, but initially it was quite controversial.

He had developed his theory of gravity to explain the cause of the mysterious motion of the planets through the sky: in a nutshell, he derived a formula for the force needed to keep a planet moving in its observed elliptical orbit, and he connected this force with everyday gravity through the experimentally derived mathematics of falling motion. Ironically (in hindsight), some of his greatest peers, like Leibniz and Huygens, dismissed the theory of gravity as “mystical” because it was “too mathematical.” As far as they were concerned, the law of gravity may have been brilliant, but it didn’t explain how an invisible gravitational force could reach all the way from the sun to the earth without any apparent material mechanism. Consequently, they favoured the mainstream Cartesian “theory”, which held that the universe was filled with an invisible substance called ether, whose material nature was completely unknown, but which somehow formed into great swirling whirlpools that physically dragged the planets in their orbits.

The only evidence for this vortex “theory” was the physical fact of planetary motion, but this fact alone could lead to any number of causal hypotheses. By contrast, Newton explained the mystery of planetary motion in terms of a known physical phenomenon, gravity; he didn’t need to postulate the existence of fanciful ethereal whirlpools. As for the question of how gravity itself worked, Newton recognized this was beyond his scope — a challenge for posterity — but he knew that for the task at hand (explaining why the planets move) “it is enough that gravity really exists and acts according to the laws that we have set forth and is sufficient to explain all the motions of the heavenly bodies…”

What’s more, he found a way of testing his theory by using his formula for gravitational force to make quantitative predictions. For instance, he realized that comets were not random, unpredictable phenomena (which the superstitious had feared as fiery warnings from God), but small celestial bodies following well-defined orbits like the planets. His friend Halley famously used the theory of gravity to predict the date of return of the comet now named after him. As it turned out, Halley’s prediction was fairly good, although Clairaut — working half a century later but just before the predicted return of Halley’s comet — used more sophisticated mathematics to apply Newton’s laws to make an even more accurate prediction.

Clairaut’s calculations illustrate the fact that despite the phenomenal depth and breadth of Principia, it took a further century of effort by scores of mathematicians and physicists to build on Newton’s work and to create modern “Newtonian” physics in the form we know it today. But Newton had created the blueprint for this science, and its novelty can be seen from the fact that some of his most capable peers missed the point. After all, he had begun the radical process of transforming “natural philosophy” into theoretical physics — a transformation from traditional qualitative philosophical speculation about possible causes of physical phenomena, to a quantitative study of experimentally observed physical effects. (From this experimental study, mathematical propositions are deduced and then made general by induction, as he explained in Principia.)

Even the secular nature of Newton’s work was controversial (and under apparent pressure from critics, he did add a brief mention of God in an appendix to later editions of Principia). Although Leibniz was a brilliant philosopher (and he was also the co-inventor, with Newton, of calculus), one of his stated reasons for believing in the ether rather than the Newtonian vacuum was that God would show his omnipotence by creating something, like the ether, rather than leaving vast amounts of nothing. (At the quantum level, perhaps his conclusion, if not his reasoning, was right.) He also invoked God to reject Newton’s inspired (and correct) argument that gravitational interactions between the various planets themselves would eventually cause noticeable distortions in their orbits around the sun; Leibniz claimed God would have had the foresight to give the planets perfect, unchanging perpetual motion. But he was on much firmer ground when he questioned Newton’s (reluctant) assumption of absolute rather than relative motion, although it would take Einstein to come up with a relativistic theory of gravity.

Einstein’s theory is even more accurate than Newton’s, especially on a cosmic scale, but within its own terms — that is, describing the workings of our solar system (including, nowadays, the motion of our own satellites) — Newton’s law of gravity is accurate to within one part in ten million. As for his method of making scientific theories, it was so profound that it underlies all the theoretical physics that has followed over the past three centuries. It’s amazing: one of the most religious, most mystical men of his age put his personal beliefs aside and created the quintessential blueprint for our modern way of doing science in the most objective, detached way possible. Einstein agreed; he wrote a moving tribute in the London Times in 1919, shortly after astronomers had provided the first experimental confirmation of his theory of general relativity:

“Let no-one suppose, however, that the mighty work of Newton can really be superseded by [relativity] or any other theory. His great and lucid ideas will retain their unique significance for all time as the foundation of our modern conceptual structure in the sphere of [theoretical physics].”

Robyn Arianrhod is an Honorary Research Associate in the School of Mathematical Sciences at Monash University. She is the author of Seduced by Logic: Émilie Du Châtelet, Mary Somerville and the Newtonian Revolution and Einstein’s Heroes. Read her previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Celebrating Newton, 325 years after Principia appeared first on OUPblog.

Thanks to Entangled Publishing for this sneak peak at Gravity, a new novel by Melissa West. Expected pub date is October 2012. I quite like this cover. Really beautiful image of space and I like the curliecues around the title. What do you think?

In the future, only one rule will matter:

Don't. Ever. Peek.

Seventeen-year-old Ari Alexander just broke that rule and saw the last

person she expected hovering above her bed - arrogant Jackson Locke, the

most popular boy in her school. She expects instant execution or some kind

of freak alien punishment, but instead, Jackson issues a challenge: help

him, or everyone on Earth will die.

Ari knows she should report him, but everything about Jackson makes her

question what she's been taught about his kind. And against her instincts,

she's falling for him. But Ari isn't just any girl, and Jackson wants more

than her attention. She¹s a military legacy who¹s been trained by her

father and exposed to war strategies and societal information no one can

know - especially an alien spy, like Jackson. Giving Jackson the

information he needs will betray her father and her country, but keeping

silent will start a war.

Visit the author online at www.melissa-west.com and follow her on Twitter @MB_West

Approaching a birthday this summer, and about to lose my vision coverage, I decided to go get my eyes checked just for the heck of it. I wasn’t having any problems seeing, but it seemed a waste to let any chance for healthcare slip away. So, I made an appointment and sat in the waiting area with all those poor people who aren’t blessed with great eyes like some of us. When I met the doctor, I confidently shook his hand, knowing that we wouldn’t be seeing anymore of each other after he checked my vision. After a couple of tests (which I breezed through with my super great eyes), I waited for the doctor to say he’s never seen such great vision in a forty-three year old and that I hav

Approaching a birthday this summer, and about to lose my vision coverage, I decided to go get my eyes checked just for the heck of it. I wasn’t having any problems seeing, but it seemed a waste to let any chance for healthcare slip away. So, I made an appointment and sat in the waiting area with all those poor people who aren’t blessed with great eyes like some of us. When I met the doctor, I confidently shook his hand, knowing that we wouldn’t be seeing anymore of each other after he checked my vision. After a couple of tests (which I breezed through with my super great eyes), I waited for the doctor to say he’s never seen such great vision in a forty-three year old and that I hav e the eyes of a teenager. But he didn’t say that. Or anything like it. What he said was, “Which frames would you like?” I was devastated. Glasses? Worse, reading glasses like some porch-rocking old lady? It’s not enough that gravity has had its way with me? I have to go blind as well? I exaggerate, of course, but I still desperately begged the doctor to tell me what I did to bring this fate upon myself and his response was, “Kept having birthdays.” Which is preferable to the alternative, but it still really stinks. In Tedd Arnold’s More Parts, one little guy goes to great lengths to protect what he’s got. I really need to start doing that.

e the eyes of a teenager. But he didn’t say that. Or anything like it. What he said was, “Which frames would you like?” I was devastated. Glasses? Worse, reading glasses like some porch-rocking old lady? It’s not enough that gravity has had its way with me? I have to go blind as well? I exaggerate, of course, but I still desperately begged the doctor to tell me what I did to bring this fate upon myself and his response was, “Kept having birthdays.” Which is preferable to the alternative, but it still really stinks. In Tedd Arnold’s More Parts, one little guy goes to great lengths to protect what he’s got. I really need to start doing that.

http://www.amazon.com/More-Parts-Tedd-Arnold/dp/0803714173

http://www.emints.org/ethemes/resources/S00002322.shtml

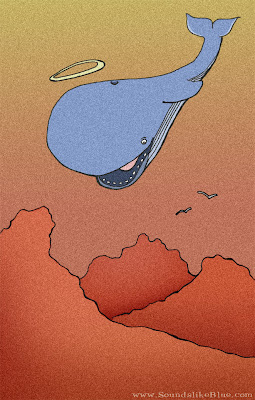

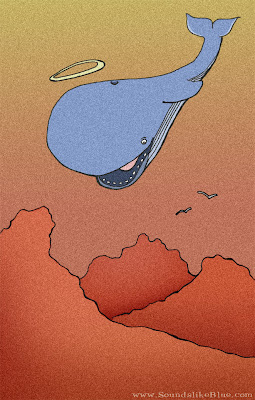

Barry the whale led a good life. He was well respected within his pod and quite popular with the ladies if you know what I mean...and I think that you do. (This was done for an Illustration Friday theme "Gravity.")

Barry the whale led a good life. He was well respected within his pod and quite popular with the ladies if you know what I mean...and I think that you do. (This was done for an Illustration Friday theme "Gravity.")

www.SoundsLikeBlue.com

Something a little different this week. I've been working on this self promotion piece on space and aliens but I won't have time to finish it this week. So this is a sketch/color comp... good to change it up and show my actual hand drawn lines.

Something a little different this week. I've been working on this self promotion piece on space and aliens but I won't have time to finish it this week. So this is a sketch/color comp... good to change it up and show my actual hand drawn lines.

cool, man! and you made me laugh!

gotta smile........that is a happy whale.....makes me think of bob ross paintings....

P