new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Siu-Lan Tan, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 5 of 5

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Siu-Lan Tan in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Charley,

on 8/7/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

critical flicker-fusion frequency,

frame rate,

illusion of motion,

Lumière Brothers,

optical illusion,

psychology of music in multimedia,

Siu-Lan Tan,

visual processsing,

Books,

film,

Alfred Hitchcock,

*Featured,

TV & Film,

Science & Medicine,

Earth & Life Sciences,

Psychology & Neuroscience,

Add a tag

By Siu-Lan Tan

Films trick our senses in many ways. Most fundamentally, there’s the illusion of motion as “moving pictures” don’t really move at all. Static images shown at a rate of 24 frames per second can give the semblance of motion. Slower frame rates tend to make movements appear choppy or jittery. But film advancing at about 24 frames per second gives us a sufficient impression of fluid motion.

However, birds–such as pigeons–have a much higher threshold for detecting movement. A bird’s visual system is keenly sensitive to moving stimuli as this is essential to their survival. Whether swooping down to snatch live prey, fleeing from a predator, or zeroing in on a nest for a precise landing, birds must rely on their fine-tuned ability to hone in on moving targets. So the frame rate at which most of our films are shown is far too slow for birds to perceive continuous motion. Their threshold of visual processing exceeds the standard frame rate, allowing them to see component frames … and the illusion of motion pictures would be broken.

If a pigeon had been roosting in the theater where 19th century crowds first gaped at the Lumière Brothers’ steam train looming towards them, it may have been less than impressed — especially as early silent films were often played at only 16 frames per second.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Even a film shown at today’s industry standard of 24 frames per second would most likely look like a series of flashing slides to a pigeon. We’re mesmerized by Marilyn Monroe’s white skirts billowing over the subway grate in The Seven-Year Itch, but a pigeon may see something more like a slide show of the skirt in frozen increments.

Further, most humans cannot distinguish individual lights flashed at 60 cycles per second, perceiving instead a single continuous beam of light. This gives an impression of constant light while watching a film (despite the shutter actually shutting out light several times per frame). But birds have much higher critical flicker-fusion frequency, such as 90-100 cycles per second or higher (e.g., Lisney et al., 2011). So while humans do not perceive the flicker in a movie, a pigeon may see flashes like strobelights along with the jumpy frames of Marilyn’s airborne skirt.

One of the creepiest scenes in Hitchcock’s The Birds shows Melanie (Tippi Hedren) smoking on a bench in a school playground while birds are flocking on a jungle gym behind her. She finally spots a lone bird flying overhead and turns around to discover every rung of the jungle gym crowded with large black birds. Actually, Hitchcock used cardboard cut-outs for most of the “birds” on the jungle gym, figuring that most people would not notice these stationary objects if interspersed with live birds.

Birds in a school playground in Hitchcock’s (1964) The Birds

Indeed, the illusion works on most of us. We are also often tricked by illusory “crowds” in films–made of real people and dummies, or multiple images of the same people patched together to make a “crowd”. However birds are especially observant of the movement of other birds–and combined with the much faster ‘refresh rate’ of the avian visual system (as their visual information is “updated” more frequently than humans)–the jungle gym scene would not likely fool any birds.

Studies suggest that birds do perceive some information via video images (using video at 30 frames per second). For instance, a video of wild chickens feeding elicits feeding in birds of the same species (McQuoid & Galef, 1993); videos showing a hawk or raccoon elicit aerial and ground alarm calls respectively in roosters (Evans, Evans, and Marler, 1993); and video images of female pigeons elicit courtship displays in male pigeons (Shimizu, 1998).

So birds seem to pick up some information from video images, at a somewhat higher frame rate and screen-refresh rate than film–though color may be distorted (Wright & Cumming, 1971), and gaps in movement and flicker are likely perceived (Lea & Dittrich, 1999). These discrepancies would be much more pronounced for moving images on cinematic film.

A fine-tuned visual system gives birds of prey an advantage when pursuing a fast-moving target. And it allows pigeons those few extra seconds to peck at grubs and seeds–and flap away at the last moment possible when your car approaches.

Nut their super-efficient processing of moving stimuli would make the cinematic experience as we know it less than spellbinding for the birds.

In conclusion: it’s interesting to note that film relies on certain limitations or imperfections of the human perceptual system for its magic to work!

Siu-Lan Tan is Associate Professor of Psychology at Kalamazoo College in Michigan, USA. She is primary editor of The Psychology of Music in Multimedia (Oxford University Press 2013), the first book consolidating the research on the role of music in film, television, video games, and computers. A version of this article also appears on Psychology Today. Siu-Lan Tan also has her own blog, What Shapes Film? Read her previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Why you can’t take a pigeon to the movies appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Charley,

on 7/10/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Music,

optical illusions,

ok go,

*Featured,

TV & Film,

Art & Architecture,

Science & Medicine,

Psychology & Neuroscience,

Siu-Lan Tan,

The Psychology of Music in Multimedia,

Gestalt psychology,

Köhler,

Koffka,

Wertheimer,

versus ‘ground’ ,

gestalt,

in gestalt,

wall”,

wall’,

shashachu,

Add a tag

By Siu-Lan Tan

When I saw OK Go’s ‘The Writing’s on the Wall’ video a few days ago, I was stunned. If you aren’t one of the over eight million people that has seen this viral music video yet, you’re in for a visual treat.

OK Go is known for creative videos, but this is the band’s richest musical collage of optical illusions so far. The most amazing part is that it was done … in one take!

Click here to view the embedded video.

Over 7.5 million viewers saw this extraordinary video in the first week it was posted.

And just newly released, OK Go uploaded this equally splendid video that gives us a ‘Behind-the-Scenes’ look.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Just a lucky coincidence?

OK Go posted ‘The Writing’s on the Wall’ on 17 June 2014. I wonder if they knew this is a significant date for Gestalt psychology? Important enough to be in the APA’s historical database for 17 June:

“June 17, 1924. Robert M. Ogden of Cornell University wrote to German psychologist Kurt Koffka, inviting him to become a visiting lecturer. This was the first step… that brought Gestaltists Koffka, Köhler, Wertheimer, and Lewin to America” (Street, 2007)

Wertheimer, Koffka, and Köhler are key figures in Gestalt psychology who laid the groundwork for what we know about perception, especially how we organize visual elements into meaningful wholes. Central to their work is the idea of ‘figure’ versus ‘ground’ – or how we distinguish the main focus (or figure) from the background or landscape in which it is set (ground).

They were also interested in perceptual illusions, influenced by psychologist Edgar Rubin who created many figure/ground illusions such as the Rubin vase, which now appears in every introductory psychology book.

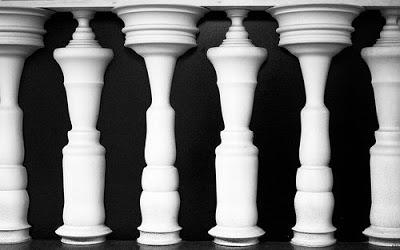

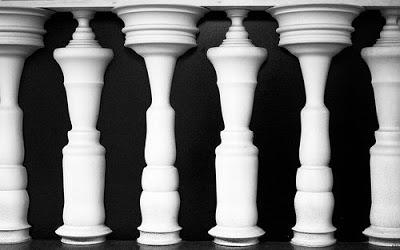

Here’s a modern version: Are these columns or five tall standing figures with bowed heads? That depends on what you take to be figure vs. ground.

OK Go’s ‘The Writing on the Wall’ plays with figure/ground relations. Many illusions in this brilliant music video ambiguate, and then disambiguate, what is foreground versus background.

This is especially well illustrated in the illusion that “the writing’s on the wall” — as it never really is. In every appearance of the written word == in the title, the blurbs in the middle, and the amazing reveal at the end — the writing’s never on the wall.

Instead, the words blend figure and ground into single alignment. The illusion works — and then is dismantled before our eyes — as the movement of objects or camera disentangle what is foreground and background.

Figure and ground seem to dissolve into each other as the musicians emerge from the red, blue, yellow shapes.

Ambiguity of where figure and ground separate is pushed even further with single images that blend foreground with distant surfaces (floors, walls): blue spots, a network of cubes, a ladder, green checkered tiles, and a row of people that appear to stand together. It’s brilliantly captured at 02:47, in the aerial image of a multi-layered apparatus that “flattens out” into a representation of drummer Tim Nordwind’s bearded face (screenshot below).

The walkthrough also takes us through the development of art: from basic shapes, to patterns (dots, stripes), to 3D (or not) cubes, geometric sculptures, and finally to representations of the human face and full body figures.

The music is not just an accompaniment to the collage of optical illusions and paradoxes, but an integral part of the work. The song is about miscommunication that can go on in a relationship. (Or is the idea of two people really ‘getting each other’ merely an illusion?)

The result is wonderfully perplexing, a delicious trick of the senses. And a fitting tribute to the 17 June landmark in Gestalt psychology.

Siu-Lan Tan is Associate Professor of Psychology at Kalamazoo College in Michigan, USA. She is primary editor of The Psychology of Music in Multimedia (Oxford University Press 2013), the first book consolidating the research on the role of music in film, television, video games, and computers. A version of this article also appears on Psychology Today. Siu-Lan Tan also has her own blog, What Shapes Film? Read her previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Optical illusion. Image by Sha Sha Chu. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via shashachu Flickr.

The post OK Go: Is the Writing on the Wall? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Charley,

on 5/29/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Videos,

Spring,

puddle,

self-efficacy,

child psychology,

Puddles,

*Featured,

Developmental Psychology,

Psychology & Neuroscience,

psychology of music in multimedia,

Siu-Lan Tan,

circular reactions,

interactional synchrony,

joint attention,

sensorimotor,

through circular,

puddles—spring,

Add a tag

By Siu-Lan Tan

It’s spring and about this time each year, a little ritual takes place. After the winter melt, many children encounter their first puddle with the zeal of an explorer discovering a new land.

Indeed, a puddle of water is a microcosm. In it, you find bits of sky, some leaves and a little froth, your own reflection. It is shallow and deep. It records your every step, augments your every move, but eventually leaves no trace that you were ever there. It is both moving and still. A mysterious thing is a puddle, and worth investigating.

After watching hours of YouTube videos of infants and toddlers stomping puddles of different sizes and shapes, I have come up with my list of “Eight Favorite Videos of Kids Discovering Puddles”—and will comment on them briefly as a developmental (child) psychologist. Take a moment to slow down and enjoy this mesmerizing medley, my ode to Spring!

#8 Boy meets first puddle

This toddler does a double-take when he first sees a puddle that has suddenly appeared in the front yard. What is that? He puts his toe in it, gasps, and takes a step back. His mother labels the experience (“Water. Puddle”), encouraging further exploration. He falls into the puddle, and gets back up again. It’s all of life in short review.

Click here to view the embedded video.

#7 Puddle splashing in Cape Breton

Ben, well-equipped in rain-gear, epitomizes Piaget’s portrait of the child as mini-scientist. Discovering a puddle for the first time, he performs repeated “tests” on this new watery universe—just like a scientist would, trying many new things to see the different effects. Piaget referred to these as circular reactions: actions repeated over and over again by the infant because the interesting effects compel the infant to try it again. Through these ‘circular reactions’, he repeatedly explores the shallow borders, touches the water with bare hands, wades into the deep middle, and examines the effects of moving in different pathways and stamping with alternating feet, on the responses of the water. His babbles punctuate his discoveries.

Click here to view the embedded video.

#6 Athena splashing in puddles—Spring 2014

Athena finds a puddle and exclaims “I’ve never seen it before!”. Piaget referred to our earliest kind of intelligence as “sensorimotor” as an infant uses her senses and motor actions to explore, and build a storehouse of knowledge about the physical world. Athena coordinates sight, touch, hearing, and action to examine the new puddle. We witness circular reactions again, this time with very fine variations. She intentionally alters the angle and speed of her foot taps, and is engrossed in observing the effects on the water—the contingencies of her actions, just like a scientist immersed in an experiment.

Click here to view the embedded video.

#5 Charlie discovers puddles

Charlie’s mother gives him time to explore on his own, and then responds to what has seized his interest. Developmental psychologists call this a joint attention episode, as child and parent are focused on the same thing. This’ joint attention episode’ is a natural teaching moment for acquiring new knowledge about the world, as well as developing language and expanding vocabulary—as the child learns all about the shared object of attention from his mother’s running commentary. “You’re in a puddle. Charlie, what does it feel like? Is it hot or cold? Is it wet or dry?”. (Charlie learns about properties of things, and new words, by direct experience). ”Do you see all the ripples you’re making? Just like the rain”. (The focus is now on cause and effect, perhaps a new word ‘ripple’). This is a master class in progress.

Click here to view the embedded video.

#4 Freya’s first puddle

Freya stops stomping puddles intermittently to look up and giggle with pure delight. While adults often dichotomize emotion and intellect, and researchers have focused mainly on the negative effects of emotion on learning, studies are beginning to suggest a link between positive emotions, such as joy and hope, and academic success (see, for example, Reinhard Pekrun). Freya’s gleeful responses show the natural joy that comes with learning, the exhilaration of discovering something new about the world around us.

Click here to view the embedded video.

#3 What if you encounter a mud puddle…when you’re driving your John Deere tractor?

This is an opportunity for Karsen to develop his cognitive skills—problem-solving—with a little advice from his father. Rather than running up to help and rescue the boy, dad instructs him on what to do from a distance. More than just the purely cognitive aspects of problem-solving, Karsen gains a sense of self-efficacy which may boost his ability on future tasks.

Click here to view the embedded video.

#2 Little girl in pink snowsuit discovers ice for the first time

This video has gone viral with almost one million views of the original post. The toddler finds a puddle that has frozen, and experiences ice for the first time. She’s somewhat younger than the other infants, and as she explores the ice patch with her feet and hands, she is constrained by her puffy snowsuit and proportions of her body. At this age, her head is one-fourth of her height (it is 1/8 in the typical adult) and her limbs are still relatively short. The consequences are worth seeing twice.

Click here to view the embedded video.

And the #1 video is… A Kid, a Dog, and a Puddle.

For this one, please read the commentary after watching.

Click here to view the embedded video.

This remarkable video has gone viral and is approaching eight million views. Okay, perhaps it’s not his first puddle but small bodies of water have not lost their luster for this boy. What’s most striking is the uncanny coordination between the boy (Arthur) and his dog (Watson), a sort of interactional synchrony (a matching of emotion and behavior, which allows for a ‘dialogue’ to take place through action). Arthur does not drop the leash carelessly but places it down gently, looking back at Watson twice—and the dog returns his gaze. The dog seems to sense the boy’s intentions and waits patiently for his companion. Arthur is immersed in sensorimotor activity through circular reactions, repeatedly running through the puddle. But he keeps his loyal dog in mind, and reunites quickly with his pal to continue their journey in step together.

As I sifted through scores of videos of infants and children stomping and splashing in puddles, I was reminded that play is a child’s work. The foundations of everything a child needs to learn across the domains—cognitive, emotional, and social—are learned through play.

This is so beautifully illustrated in a moment of curiosity, discovery, and joy of a child, evoked by a small pool of water left after the rain.

Siu-Lan Tan is Associate Professor of Psychology at Kalamazoo College in Michigan, USA. She is primary editor of The Psychology of Music in Multimedia (Oxford University Press 2013), the first book consolidating the research on the role of music in film, television, video games, and computers. A version of this article also appears on Psychology Today. Siu-Lan Tan also has her own blog, What Shapes Film? Read her previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Jack in Puddle Photo by Robert Murphy. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Robert Murphy Flickr.

The post Splash! What kids discover in a puddle appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Charley James,

on 4/24/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

lara,

Expressiveness,

music psychology,

Siu-Lan Tan,

Mini Maestro,

The Psychology of Music in Multimedia,

conductor’s motions,

little lara,

recognizes agogic,

child psychology,

*Featured,

Conductor,

Developmental Psychology,

Psychology & Neuroscience,

Andrew Koehler,

Add a tag

By Siu-Lan Tan

Sometimes you think you can explain something, and then it turns out you really can’t. This remarkable video was posted last year but only went viral in the US in the last few weeks, approaching 5 million hits in a short time. When I first saw it, I was immediately enchanted.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Dubbed by the press as ‘the Mini Maestro’ (although to be correct, she would be a maestra), the video shows little Lara Glozou with a church choir in Kyrgyzstan. She’s the young daughter of one of the choir members and often attends rehearsal.

After watching a few times, I thought I knew what might be happening. This must be an observant child who’s mirroring the actions of a conductor standing in front of the choir, interspersed with a little improvisation of her own. I thought she was a remarkable imitator, not just able to capture the conductor’s motions, but also the emotions.

But then I found another video. It shows the choir rehearsing the same song from another angle, allowing us to see the conductor’s motions of the right hand while Lara is gesturing expressively in the far right corner by the piano.

Click here to view the embedded video.

I was amazed to see that the conductor is not making the same kinds of motions as Lara after all. Even though the conductor’s gestures may be outlining the regularity of the beat and phrasing, many of Lara’s gestures and body movements—the forward lean, the hand to the chest, the sway of the body, and the dips and turns of the head—seem to be her own.

To be fair, Lara is not really “conducting.” If she were directing, her motions would come slightly before the events in the music, in anticipation of them in order to cue the choir. Her movements are more like an expression of the music. However, as an expression or sensitive interpretation of the music, I find her gestures to be remarkable. Truly extraordinary. For instance, her gestures are fewer and more prolonged during the female solo up to 0:21 (on the first video). They are a series of poses. But at 0:22 when the choir comes in, she immediately shifts to grand sweeping gestures. The variety of shapes that she forms with her hands alone express a rainbow of emotions and tone colors.

I am in awe of this little girl’s ability not only to reflect peaks and valleys in the melody of the music, and momentum of the phrases, but also the shape of the sound. For the last note of the song, she curves her left and right hands into the widest arcs for a broad final tone — a lion’s roar — rather than the kind of ending that gradually fades away.

This small child has had so little time on earth to experience falling in love, the sting of heartbreak, betrayal, triumph, grief, pain, and the rest of the great emotional topography of life. How is she able to convey the semblance of emotional depth and angst? Where is she getting her musical sensitivity? Do some young children just have an old soul?

As a former music major, I took Conducting 101. My spine was rigid, my gestures were tiny and angular. As a music student in my 20s, I had none of the intensity and theatrical weight of this little girl. More recently, I have written about how infants begin to spontaneously respond to music in bodily ways, nodding their heads and waving arms to rhythmic music once they are able to sit freely at about six months. Later, bobbing up and down with knee-bends, and spinning around in circles to music between one and two years, after they become mobile.

However, they do so for only short bursts, and most of the movements of two- and three-year-old children don’t really match the music in time (Moog, 1976; Malbrán, 2000). Although Lara is not always synchronized with the music, her deep expressive gestures capture the musical events in a broad way, even anticipating some musical moments, as she is familiar with this piece.

Little is known about young children’s interpretation of music. In one of the few studies in this area, Boone & Cunningham (2001) showed that four-year-olds can move a flexible teddy bear in dance-like fashion, to express emotion in music through movement. However the musical emotions they recognized and expressed were basic emotions (such as happiness, or sadness, or anger). What we seem to observe in Lara is much more nuanced. How is she able to capture this depth in music?

I spoke with a grown-up maestro that I greatly admire, Andrew Koehler, Music Director of the Kalamazoo Philharmonia. He said, “It’s really astonishing. Lara moves in a way that shows that she recognizes agogic accents“ (longer durations of tones, which give natural stress to music). She often reflects this with larger, more expansive motions of her arms that mark those accents.

Her gestures also capture finer details. At 0:45 to 0:47 in the first video, Koehler points out how a higher tone of greater tension resolves to a lower tone of lower tension. The toddler reflects this: “Lara leans into the music, her right hand pushing into it with a claw-like motion [capturing high tone and high tension in the music]. Then both left and right arms make downward motions as her posture goes back to an upright position again [lower tone, lower tension].”

And then there’s Jonathan Okseniuk. Here he is at three years old, appearing to ‘conduct’ a recording of the last movement of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony in his home in Mesa, Arizona.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Even if he appears to be getting some coaxing off camera, this is a remarkable three-year-old.

Here is Jonathan again at age four, conducting a live orchestra in a rousing rendition of Khachaturian’s ‘Sabre Dance’. “This is a more challenging arena,” explains Koehler, “which would require Jonathan to anticipate what will happen in the music as opposed to simply responding to it.”

Click here to view the embedded video.

There are many other videos of Jonathan on the web, conducting Beethoven, Brahms, Mozart, and Strauss with different orchestras.

How an understanding of music blooms so early in some young ones astonishes me. This mini-maestra’s sensitive expression of music and mini-maestro’s early conducting chops have left me perplexed.

Siu-Lan Tan is Associate Professor of Psychology at Kalamazoo College in Michigan, USA. She is primary editor of The Psychology of Music in Multimedia (Oxford University Press 2013), the first book consolidating the research on the role of music in film, television, video games, and computers. A version of this article also appears on Psychology Today. Siu-Lan Tan also has her own blog, What Shapes Film? Read her previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Mini maestro mystifies me appeared first on OUPblog.

By: KatherineS,

on 4/17/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Music,

Videos,

video games,

*Featured,

Arts & Leisure,

Psychology & Neuroscience,

Sports & Games,

psychology of music in multimedia,

Siu-Lan Tan,

dubaj,

visual game,

dataspel,

game doom with,

playing twilight,

game ridge,

the game,

Add a tag

By Siu-Lan Tan

When playing video games, do you play better with the sound on or off? Every gamer may have an opinion, but what has research shown?

Some studies suggest that music and sound effects enhance performance. For instance, Tafalla (2007) found that male gamers scored almost twice as many points while playing the first-person shooter game DOOM with the sound on (chilling music, weaponfire, screams, and labored breathing) compared to those playing with the sound off.

On the other hand, Yamada et al. (2001) found that people had the fastest lap times in the racing game Ridge Racer V when playing with the music off. Interestingly, 10 different music tracks were tested—and the lowest scores were earned when playing with the soundtrack built into the game (Boom Boom Satellite’s “Fogbound”).

Sometimes the results are more complex. Cassidy and MacDonald (2009) tested people playing a driving game with car sounds effects alone or with car sound effects plus different kinds of music. People playing with music that had been shown to be ‘highly arousing’ (in previous research) drove the fastest—but also made the greatest number of mistakes, such as hitting barriers or knocking over road cones!

In our own research (published 2010 and 2012), my colleagues John Baxa and Matt Spackman and I found that people playing Twilight Princess (Legend of Zelda) performed worst when playing with both music and sound effects off. This game provides the player with rich auditory cues that function as warnings, clues for access points, feedback for correct moves such as successful attacks on enemies, and more. Many of these don’t just “double” what you see on the screen.

As we progressively added more game audio, performance improved. However, surprisingly, our participants performed best when playing with background music playing on a boombox that was unrelated to the game! (This would be like playing a game with the game sound switched off—while your roommate’s music is playing in the background.)

How to boost your game play?

So how do we make sense of these findings? And do they shed light on what distinguishes the top gamers?

A closer look at the individuals in our 2010/2012 study suggested that the majority of our participants—but not all—played better with unrelated background music until they “got the hang of” the game.

We used a game that was new to everybody. As Twilight Princess is a pretty complex adventure role-playing game, the average player seemed to have to focus attention on the visual information when first navigating the game. So music and sound effects built into the game may have interfered with their concentration, as they had to “tune it out” to focus on visual cues to guide their actions at first.

However, our top players (who concluded four days of play in our Videogame Lab with the highest scores) were different. They tended to play better with the game sound on (full music and sound effects coming from both screen and Wiimote) from the very beginning.

The best players seemed to be better at paying attention to and meaningfully integrating both audio and visual cues effectively—thus benefitting from the richest warnings/clues/feedback. While the typical player strongly favored one sense, the best players were truly playing an audio-visual game from the beginning.

So…one secret to being a successful gamer may be to sharpen your attention to audio cues (in sound effects and music) within a game. Paying more attention to and integrating cues to both ear and eye may boost your game!

More than just high scores…

I’m also reminded of what a participant in our study expressed so well: “There’s more to a game than just high scores. It’s also about being transported and immersed in another world, and music and sound effects are what bring you there.”

Indeed, the lush cinematic scores take us through the emotional highs and lows of the journey of a game. Atmospheric tracks immerse us in other worlds. Rhythmic tracks serve as an engine to drive the action, the propulsion of the music making the virtual environment appear deeper and the visual array seem to whizz by faster (motion parallax).

When you have a great soundtrack, music can be the soul of a game.

Postscript: Sonic Mayhem!

Recently I had a chance to speak with composer Sonic Mayhem (Sascha Dikiciyan) when we were both interviewed on video game music by Sami Jarroush for Consequence of Sound. Sonic Mayhem is one of the most sought-after video game music composers today. He scored Quake III Arena, Tron: Evolution, Mass Effect 2 & 3, Borderlands, Space Marine, James Bond: Tomorrow Never Dies, Mortal Kombat vs DC, and a ton of other monumental games.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Siu-Lan Tan is Associate Professor of Psychology at Kalamazoo College in Michigan, USA. She is primary editor of The Psychology of Music in Multimedia (Oxford University Press 2013), the first book consolidating the research on the role of music in film, television, video games, and computers. A version of this article also appears on Psychology Today. Siu-Lan Tan also has her own blog, What Shapes Film? Read her previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Dubaj, by Danik9000, CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Dataspel, by Magnus Fröderberg/norden.org, CC-BY-2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What’s the secret to high scores on video games? appeared first on OUPblog.