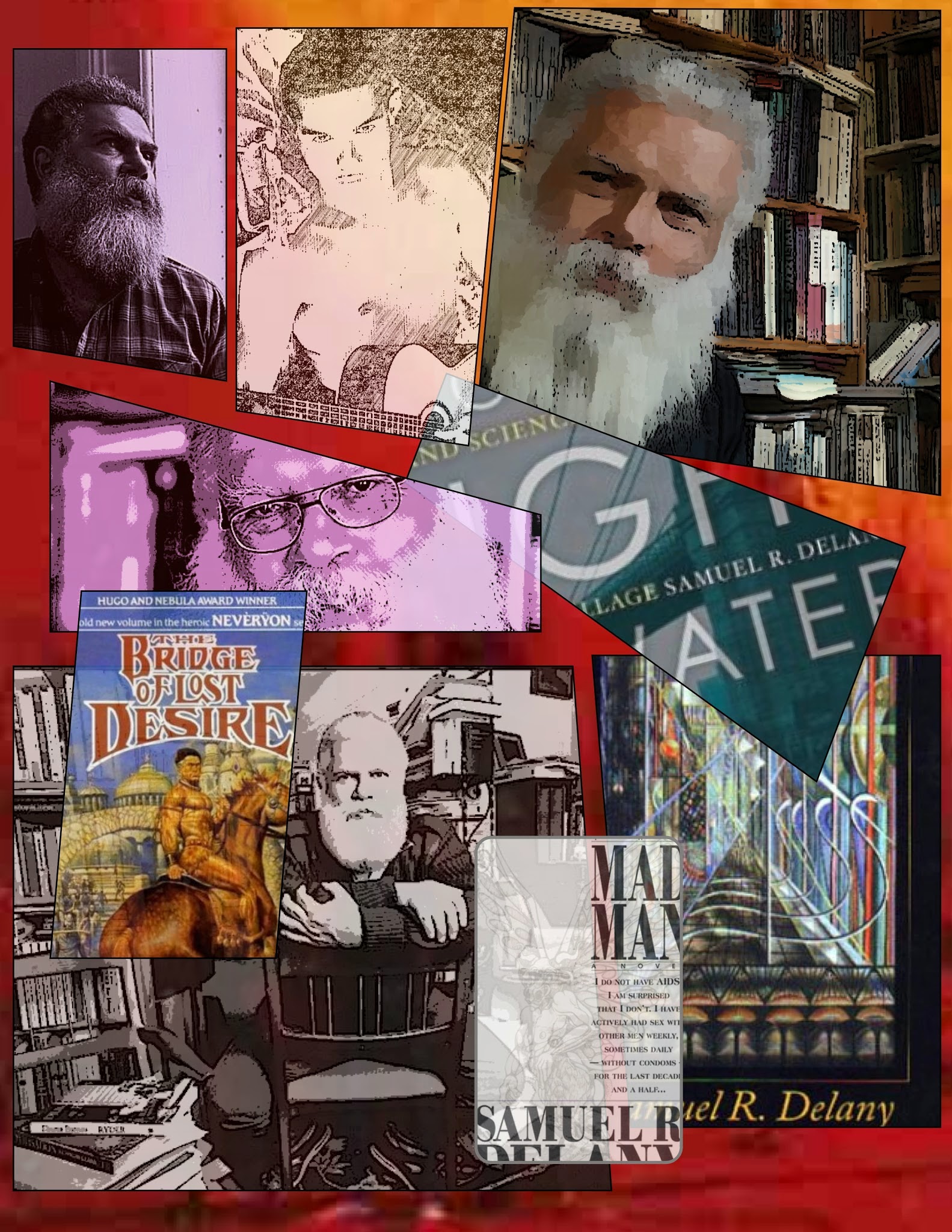

Recently, Locus published an online discussion of the work of Samuel R. Delany with a bunch of different writers and critics, primarily aimed at discussing Delany’s status as the newly-crowned Grand Master of the Science Fiction Writers of America. Plenty of interesting things are said there, and the participants include a number of people I’m very fond of (both as writers and people), but the particular focus ended up, I thought, creating a certain narrowness to the discussion, especially regarding the post-Dhalgren works, and I thought it might be nice to gather a different group of people together to discuss Delany … differently.

So here we are. I put out the call to a wide variety of folks, and this is the group that responded. We used a Google Doc, and the discussion grew rhizomatically more than linearly, so you'll see that we sometimes refer to things said later in the roundtable. (This makes for a richer discussion, I think, but it may be a little jarring if you expect a linear conversation.)

So here we are. I put out the call to a wide variety of folks, and this is the group that responded. We used a Google Doc, and the discussion grew rhizomatically more than linearly, so you'll see that we sometimes refer to things said later in the roundtable. (This makes for a richer discussion, I think, but it may be a little jarring if you expect a linear conversation.)

I hope people who didn't have time or ability to join us in the "official" roundtable will feel free to offer their thoughts in the comments — as will, well, anybody else. Therefore, without further ado and all that jazz...

PARTICIPANTS

PARTICIPANTS

Matthew Cheney has published fiction and nonfiction in a wide variety of venues, including One Story, Locus, Weird Tales, Rain Taxi, and elsewhere. He wrote the introductions to Wesleyan University Press’s editions of Samuel R. Delany’s The Jewel-Hinged Jaw, Starboard Wine, and The American Shore (forthcoming). Currently, he is a student in the Ph.D. in Literature program at the University of New Hampshire.

Craig Laurance Gidney is the author of Sea, Swallow Me & Other Stories and the YA novel Bereft.

Geoffrey H. Goodwin is a journalist, author, and rogue academic with a Bachelor’s in Literary Theory (Syracuse University) and an MFA in Creative Writing (Naropa University). Geoffrey writes fiction; has taught composition and creative writing in a wide range of settings; has interviewed speculative writers and artists for Bookslut, Tor.com, Sirenia Digest, The Mumpsimus, and during Ann Vandermeer’s helming of Weird Tales; and has worked in seven different stores that have sold comic books.

Keguro Macharia is a recovering academic, a lazy blogger, and an itinerant tweeter. Sometimes, he writes things on gukira.wordpress.com or tweets as @Keguro_

Nick Mamatas is the author of several novels, including Love is the Law and The Last Weekend. His short fiction has appeared everywhere from Asimov’s Science Fiction to The Mammoth Book of Threesomes and Moresomes.

Njihia Mbitiru is a screenwriter. He lives in Nairobi.

Lavelle Porter is an adjunct professor of English at New York City College of Technology (CUNY) and a Ph.D. candidate in English at the CUNY Graduate Center. His dissertation The Over-Education of the Negro: Academic Novels, Higher Education and the Black Intellectual will be completed this spring. Finally. He’s on Twitter @alavelleporter.

Ethan Robinson blogs, mostly about science fiction, at maroonedoffvesta.blogspot.com, a position he will no doubt shortly be parlaying into literary fame.

Eric Schaller is a biologist, writer, and artist, living in New Hampshire and co-editor of The Revelator.

THE ROUNDTABLE

Matthew Cheney

How has Delany influenced your own work or views on writing and literature?

|

| detail of the cover of Dhalgren (Bantam, 1975) |

Geoffrey H. Goodwin:

I got to spend a week with Chip, most minutes of every day, when he came and taught at my summer writing program when I was getting an MFA. A friend and I were the two second year science fiction devotees in the prose program (still not an easy spot in academe, though Chip has made that easier), so we knew that one of us could be his teaching assistant and decided to take it into our own hands. I remember the day Anne Waldman found out Chip was coming. I was in a poetry workship with her that day, so I raced to my friend and I swapped a fight over T.A.-ing for Chip to T.A. for Brian Evenson [who, by my reckoning, said some of the wisest comments in the other Delany roundtable] under the express agreement that my friend and I would both follow Chip around the whole time. So we did. Life-changing. Chip is still helping me learn and comprehend both literature and writing. His About Writing is one of my favorite books on the subject.

If one looks at his criticism, fiction, memoirs, and cultural relevance--not to mention everything else he’s accomplished--he’s incomparable. Sure, I remember how he offered the particle theory, where we read and read and then emit a particle on our own when we write, inspired by how we bombarded ourselves; or how he made sure to place the Marquis de Sade’s books within his young daughter’s reach because he wanted her to make her own choices about literature, and there were lessons and exercises in the workshop that were profound--but I also think of Chip as someone with whom I got to trade stories about Allen Ginsberg for stories about Philip K. Dick and Clive Barker. He’s a constellation in a tiny pantheon of living geniuses.

Nick Mamatas

I guess I appreciate Delany more as a reader than anything else. He doesn’t influence my writing, or my views. There are aspects of agreements, but I haven’t changed my mind about anything to coincide with Delany’s views. I always assign his book on writing—I’ve probably sold an extra fifty copies so far—not because I agree with everything in it, but because everything in it is worth tangling with.

Ethan Robinson

If one looks at his criticism, fiction, memoirs, and cultural relevance--not to mention everything else he’s accomplished--he’s incomparable. Sure, I remember how he offered the particle theory, where we read and read and then emit a particle on our own when we write, inspired by how we bombarded ourselves; or how he made sure to place the Marquis de Sade’s books within his young daughter’s reach because he wanted her to make her own choices about literature, and there were lessons and exercises in the workshop that were profound--but I also think of Chip as someone with whom I got to trade stories about Allen Ginsberg for stories about Philip K. Dick and Clive Barker. He’s a constellation in a tiny pantheon of living geniuses.

Nick Mamatas

I guess I appreciate Delany more as a reader than anything else. He doesn’t influence my writing, or my views. There are aspects of agreements, but I haven’t changed my mind about anything to coincide with Delany’s views. I always assign his book on writing—I’ve probably sold an extra fifty copies so far—not because I agree with everything in it, but because everything in it is worth tangling with.

Ethan Robinson

While discussions of Delany often focus on the beauty of his prose, his skillful "way with words" (usually with an example of some passage of heightened sensory description), for me this obscures one of the most remarkable aspects of his writing. It is true that he can indeed write quite beautifully when he needs to, but he is also willing to let himself write badly--that is, to take on modes of writing that are usually considered bad, clumsy, and really get to the heart of what it is that these modes are doing. I think in particular (but not exclusively) of his dialogue, which I find is very much of a piece with the generally derided style of the American science fiction magazines in its matter-of-factness, its often nakedly expository nature--even sometimes its flatness and lack of differentiation. For me it often calls to mind, say, the tendency of characters in Asimov and, later, McCaffrey (just two examples out of many possible) to talk to one another with bizarre thoroughness and "rational objectivity" about their own psychological makeups. In Delany the contrast between these passages of unattractive writing on the one hand and the heightened "poetic" passages on the other becomes a sort of structuring element, one that I think has been underappreciated and underexamined. And for myself, struggling in my own writing with the received notion that one must write "beautifully" (and/or inconspicuously; implied in both: homogeneously), seeing the value of occasional downright ugliness in Delany's writing has been very emboldening.

Keguro Macharia

I’ll lift Matt’s second prompt below--on beginnings--and track back to the Locus conversation, which started with “beginnings”: when did you first encounter Delany? Which is also a question about SF as a genre that (to my mind) obsesses about beginnings and endings (ecocides, genocides, monsters, hybrids, extinguishment, survival). Which is also to borrow from Lavelle about AIDS and Delany and, more broadly, the forms of extinguishment and disposability his work speaks to and, in doing so, enables us to speak about--this is the importance of Hogg as an early work. I first encountered Delany in the Patrick Merla anthology (Boys Like Us) that Lavelle mentions below. I don’t remember reading him then and, in fact, I suspect that I did not know how to read him at the time--I wanted a simple(r) narrative than he was willing to offer, a cleaner story that stayed “inside the lines,” affirmed identity, made the pleasures of identification simple, the practices of belonging uncomplicated. (Although Matt wants us to be polite, I’ll add that I read much of this impulse in the Locus discussion.)

I re-encountered Delany through Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, just before I joined grad school. At the time, I was interested in formal innovation, and Times Square modeled the kind of writing and thinking I found necessary as a form of world building. I came to the novels later--Stars in My Pocket, Hogg, Mad Man, the Nevèrÿon series, at much the same time as I was reading Delany’s many essay collections. Delany helped me see form--why form matters, how form matters, to whom form matters, why formalism matters--as a project of world-building, world-remaking, inextricable from embodiment, desire, fantasy, and speculation.

Njihia Mbitiru

I have absolutely no idea, yet, about his influence on me. Others have spoken with great perspicacity--as well as humor (Brett Cox in the Locus roundtable being one)--about Delany’s influence. I suspect I’m still working through mine and therefore limited in what I can say about it. The first bit of Delany’s writing I encountered was The Towers of Toron, the first in the Fall of the Towers Trilogy. I was twenty-one, if I recall correctly. That was twelve years ago now. I’ve become an avid re-reader of his work, which has made me a re-reader of many other writers I onced-over. And because of this I would very much like to hazard that I am now a better reader, but this also remains to be seen: the simple fact is that proof of such is in writing, whose excellence, much as we strive toward our own finally idiosyncratic sense of it, is also a public affair.

Matt: just to touch on what you’ve said about the narrative of certain of his writings--the later ones, beginning with Dhalgren (written in his late 20s and early 30s, you’ll recall! so that it’s hard to think of this as ‘late Delany’): I also resist and reject this narrative ( I’m not quite at resentment, but give me time). I find it completely non-sensical. Better and more honest to say, as a reader, that the game he’s hunting as a novelist in Dhalgren, Triton, the Neveryon series up into his present work doesn’t hold your interest. It’s a long way away from that to ‘difficult’. Only a very narrow reading of SF writing would support an assessment of Delany as ‘difficult’, if we’re talking about prose style (though I suspect that’s not what is meant, which begs the question: what do people mean exactly when they use the term ‘difficult’?). There’s so much at a SF readers’ disposal in terms of range and sophistication, or if you like, the absence of it, as there is in any other genre. I enjoy and appreciate Delany’s writing in no small part because it calls attention to precisely this.

Eric Schaller

Delany’s writings have influenced me more in my approach to life and thought than in writing itself. Some may dislike John Gardner’s concept and application of ‘moral fiction’ to literature, but I have always found Delany’s work moral in its suggestion of how to live a good life. In this respect, as a philosophy, I could abbreviate it as ‘compassionate individualism’: the importance of discovering and following your own path, the diversity of such paths within a population, and how to maintain your personal dignity without selfishly depriving others of theirs. The dedication in Heavenly Breakfast ("This book is dedicated to everyone who ever did anything no matter how sane or crazy whether it worked or not to give themselves a better life"), when I read it in college brought tears to my eyes, and still does.

Through Delany’s writings, I like to think that I became more intentionally aware. My discovery that Delany was gay—not necessarily obvious from his earlier novels, which featured plenty of male-female couples, or from his earlier biographical information which sometimes mentioned a marriage—more specifically the worlds revealed in his non-fictional/autobiographical works such as The Motion of Light in Water, the contemporary sections from “The Tale of Plagues and Carnivals,” and, more recently, Times Square Red, Times Square Blue personified concerns that I would never experience directly. I donate to GMHC because of these works.

Keguro Macharia

I’ll lift Matt’s second prompt below--on beginnings--and track back to the Locus conversation, which started with “beginnings”: when did you first encounter Delany? Which is also a question about SF as a genre that (to my mind) obsesses about beginnings and endings (ecocides, genocides, monsters, hybrids, extinguishment, survival). Which is also to borrow from Lavelle about AIDS and Delany and, more broadly, the forms of extinguishment and disposability his work speaks to and, in doing so, enables us to speak about--this is the importance of Hogg as an early work. I first encountered Delany in the Patrick Merla anthology (Boys Like Us) that Lavelle mentions below. I don’t remember reading him then and, in fact, I suspect that I did not know how to read him at the time--I wanted a simple(r) narrative than he was willing to offer, a cleaner story that stayed “inside the lines,” affirmed identity, made the pleasures of identification simple, the practices of belonging uncomplicated. (Although Matt wants us to be polite, I’ll add that I read much of this impulse in the Locus discussion.)

I re-encountered Delany through Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, just before I joined grad school. At the time, I was interested in formal innovation, and Times Square modeled the kind of writing and thinking I found necessary as a form of world building. I came to the novels later--Stars in My Pocket, Hogg, Mad Man, the Nevèrÿon series, at much the same time as I was reading Delany’s many essay collections. Delany helped me see form--why form matters, how form matters, to whom form matters, why formalism matters--as a project of world-building, world-remaking, inextricable from embodiment, desire, fantasy, and speculation.

Njihia Mbitiru

I have absolutely no idea, yet, about his influence on me. Others have spoken with great perspicacity--as well as humor (Brett Cox in the Locus roundtable being one)--about Delany’s influence. I suspect I’m still working through mine and therefore limited in what I can say about it. The first bit of Delany’s writing I encountered was The Towers of Toron, the first in the Fall of the Towers Trilogy. I was twenty-one, if I recall correctly. That was twelve years ago now. I’ve become an avid re-reader of his work, which has made me a re-reader of many other writers I onced-over. And because of this I would very much like to hazard that I am now a better reader, but this also remains to be seen: the simple fact is that proof of such is in writing, whose excellence, much as we strive toward our own finally idiosyncratic sense of it, is also a public affair.

Matt: just to touch on what you’ve said about the narrative of certain of his writings--the later ones, beginning with Dhalgren (written in his late 20s and early 30s, you’ll recall! so that it’s hard to think of this as ‘late Delany’): I also resist and reject this narrative ( I’m not quite at resentment, but give me time). I find it completely non-sensical. Better and more honest to say, as a reader, that the game he’s hunting as a novelist in Dhalgren, Triton, the Neveryon series up into his present work doesn’t hold your interest. It’s a long way away from that to ‘difficult’. Only a very narrow reading of SF writing would support an assessment of Delany as ‘difficult’, if we’re talking about prose style (though I suspect that’s not what is meant, which begs the question: what do people mean exactly when they use the term ‘difficult’?). There’s so much at a SF readers’ disposal in terms of range and sophistication, or if you like, the absence of it, as there is in any other genre. I enjoy and appreciate Delany’s writing in no small part because it calls attention to precisely this.

Eric Schaller

Delany’s writings have influenced me more in my approach to life and thought than in writing itself. Some may dislike John Gardner’s concept and application of ‘moral fiction’ to literature, but I have always found Delany’s work moral in its suggestion of how to live a good life. In this respect, as a philosophy, I could abbreviate it as ‘compassionate individualism’: the importance of discovering and following your own path, the diversity of such paths within a population, and how to maintain your personal dignity without selfishly depriving others of theirs. The dedication in Heavenly Breakfast ("This book is dedicated to everyone who ever did anything no matter how sane or crazy whether it worked or not to give themselves a better life"), when I read it in college brought tears to my eyes, and still does.

Through Delany’s writings, I like to think that I became more intentionally aware. My discovery that Delany was gay—not necessarily obvious from his earlier novels, which featured plenty of male-female couples, or from his earlier biographical information which sometimes mentioned a marriage—more specifically the worlds revealed in his non-fictional/autobiographical works such as The Motion of Light in Water, the contemporary sections from “The Tale of Plagues and Carnivals,” and, more recently, Times Square Red, Times Square Blue personified concerns that I would never experience directly. I donate to GMHC because of these works.

Matthew Cheney

There seems to be a narrative among science fiction fans, and particularly SF fans of a certain age, that there is The Good Delany of the pre-Dhalgren books, Hugo and Nebula Awards, etc. ... and then there is The Problematic Delany of Dhalgren and later. It’s a narrative of loss and disappointment, frequently accompanied by the question, “What happened?!” Because I was born in the year Dhalgren was, at least officially, published (it bears a January 1975 publication date, though it actually hit shelves a little earlier), and didn’t start reading Delany until either late 1987 or sometime in 1988, when the last Nevèrÿon book, The Bridge of Lost Desire (Return to Nevèrÿon) was published, my awareness of his career has always included what older, more traditional SF readers considered the “difficult” writings. It’s probably not surprising that I resist, reject, and resent this narrative.

The book I’ve spent the most time with recently, because I’m working on a conference paper about it, is Dark Reflections, which is really beautiful and much more complexly structured than it seems at first, and which should be accessible to just about any audience, since it’s not at all pornographic and the complexity of the structure is subtle, making a basic reading relatively easy. Also, the book’s a great companion to About Writing, which it echoes often. (There’s some good discussion of the “accessibility” of Dark Reflections, particularly for heterosexual men, in Delany’s 2007 interview with Carl Freedman in Conversations with Samuel R. Delany.) But for various reasons, some having to do with events in the publishing industry, Dark Reflections does not seem to have been widely read, and is currently only in print as an e-book. It deserves a wide audience, though.

So my questions for the roundtable are: What other, more useful, stories of Delany’s career could we tell? Is the Good Delany/Problematic Delany narrative useful in some way that I’m missing, some way that I can’t see because it just makes me so angry?

Ethan Robinson

There seems to be a narrative among science fiction fans, and particularly SF fans of a certain age, that there is The Good Delany of the pre-Dhalgren books, Hugo and Nebula Awards, etc. ... and then there is The Problematic Delany of Dhalgren and later. It’s a narrative of loss and disappointment, frequently accompanied by the question, “What happened?!” Because I was born in the year Dhalgren was, at least officially, published (it bears a January 1975 publication date, though it actually hit shelves a little earlier), and didn’t start reading Delany until either late 1987 or sometime in 1988, when the last Nevèrÿon book, The Bridge of Lost Desire (Return to Nevèrÿon) was published, my awareness of his career has always included what older, more traditional SF readers considered the “difficult” writings. It’s probably not surprising that I resist, reject, and resent this narrative.

The book I’ve spent the most time with recently, because I’m working on a conference paper about it, is Dark Reflections, which is really beautiful and much more complexly structured than it seems at first, and which should be accessible to just about any audience, since it’s not at all pornographic and the complexity of the structure is subtle, making a basic reading relatively easy. Also, the book’s a great companion to About Writing, which it echoes often. (There’s some good discussion of the “accessibility” of Dark Reflections, particularly for heterosexual men, in Delany’s 2007 interview with Carl Freedman in Conversations with Samuel R. Delany.) But for various reasons, some having to do with events in the publishing industry, Dark Reflections does not seem to have been widely read, and is currently only in print as an e-book. It deserves a wide audience, though.

So my questions for the roundtable are: What other, more useful, stories of Delany’s career could we tell? Is the Good Delany/Problematic Delany narrative useful in some way that I’m missing, some way that I can’t see because it just makes me so angry?

Ethan Robinson

I’ve not yet read any of his fiction after Trouble on Triton (at a certain point I decided to approach him chronologically and have been stalled at The Einstein Intersection, which my library doesn't have; I should just go ahead and buy it, probably), and haven't in fact read Dhalgren, so I can't say too much about this. But I will say that the way I see people talk about this is always very distressing to me as many of the points singled out as "problems" (too many "ideas," not enough action, unconventional storytelling, etc.) are precisely what draws me not only to Delany but to science fiction in the first place! I know the bulk of sf has always been written on a pretty, shall we say, basic level, but I confess I simply have no idea why people who want nothing but simplicity and action and conventional narrative would be attracted to this field, which seems to long for much more.

Craig Laurance Gidney

My first introduction to Delany was, interestingly enough, Dhalgren. My older brother had a copy of the book when it first came out in the ‘70s and I appropriated it. I read the book in bits and pieces during my teenaged years, and it formed my taste for esoteric and trippy SF. When people spoke about how difficult the book was, I had a hard time understanding them, maybe because I absorbed the idea of the non-linear and counter-factual texts so young. Everything of his I read is through the locus of Dhalgren. The earlier stuff is great to me because I can see the progression of themes that were refined in his later work.

Eric Schaller

Craig Laurance Gidney

My first introduction to Delany was, interestingly enough, Dhalgren. My older brother had a copy of the book when it first came out in the ‘70s and I appropriated it. I read the book in bits and pieces during my teenaged years, and it formed my taste for esoteric and trippy SF. When people spoke about how difficult the book was, I had a hard time understanding them, maybe because I absorbed the idea of the non-linear and counter-factual texts so young. Everything of his I read is through the locus of Dhalgren. The earlier stuff is great to me because I can see the progression of themes that were refined in his later work.

Eric Schaller

I think some of the variable responses to Delany’s work may arise in part from what piece(s) were initially encountered, and how such initial experiences play into future expectations. I first encountered Delany’s work through several short stories read in high school. I remember how strongly “Time Considered as a Helix of Precious Stones” affected me, and took a perverse pleasure in the fact that my Dad didn’t follow the main character’s morphing names in the initial section. I also remember reading “Aye, and Gomorrah,” in Dangerous Visions, a story that I knew had to be important because Harlan Ellison said so. At first the story seemed slight, but it lingered and poked at my consciousness.

I don’t think I read a novel of Delany’s until the summer after graduating high school. I was working in New York City at Sloan Kettering and the novel was Dhalgren. There had been the joke published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction about the three things that mankind would never reach (“The core of the sun, the speed of light, and page 30 of Dhalgren”), but this if anything incited my interest in the novel. I was of the right age and in the right place to have the novel assume a central station in my life. But it is also one of those novels that I have returned to and re-read over the years, each time taking something new away from it. For instance, Delany having written that The Fall of the Towers was inspired by a painting of that title which did not show towers but rather reactions to their fall, I noticed a similar approach was often used in Dhalgren: the reactions of characters described before you understood to what they were reacting.

As an undergraduate at Michigan State, I sought out every Delany book I could find. And to my mind then, and still, there were differences in the approach to writing found in his early works to what I found in Dhalgren and the Return to Nevèrÿon series. The closest I can come to that difference is to say that in the earlier work Delany seemed to be thinking at a sentence to sentence level. With the later work, it seemed that he inhabited whole paragraphs at once; an individual sentence might not seem that powerful or poetic alone, but within the context of the paragraph it sang.

Geoffrey H. Goodwin

I don’t think I read a novel of Delany’s until the summer after graduating high school. I was working in New York City at Sloan Kettering and the novel was Dhalgren. There had been the joke published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction about the three things that mankind would never reach (“The core of the sun, the speed of light, and page 30 of Dhalgren”), but this if anything incited my interest in the novel. I was of the right age and in the right place to have the novel assume a central station in my life. But it is also one of those novels that I have returned to and re-read over the years, each time taking something new away from it. For instance, Delany having written that The Fall of the Towers was inspired by a painting of that title which did not show towers but rather reactions to their fall, I noticed a similar approach was often used in Dhalgren: the reactions of characters described before you understood to what they were reacting.

As an undergraduate at Michigan State, I sought out every Delany book I could find. And to my mind then, and still, there were differences in the approach to writing found in his early works to what I found in Dhalgren and the Return to Nevèrÿon series. The closest I can come to that difference is to say that in the earlier work Delany seemed to be thinking at a sentence to sentence level. With the later work, it seemed that he inhabited whole paragraphs at once; an individual sentence might not seem that powerful or poetic alone, but within the context of the paragraph it sang.

Geoffrey H. Goodwin

Re-reading the original Locus Roundtable, I can see how some of the context shifted based on the idea of “Samuel R. Delany, Grandmaster.” I know I think differently when “Grandmaster” gets added after anything and then we get the added aspect of, “Welcome to the Science Fiction canon,” by writers who, for no fault of their own, are far less accomplished than Chip. So we have a gay black beatnik who writes science fiction, essays, porn, comics, criticism, and just about everything else—and Chip is the kind of writer who can mean many different things to many different people. Paul Witcover’s review comparing Delany to Hendrix and Bowie really resonates with how I see Chip’s work—but Chip has kept at the work, continuing to evolve. F. Brett Cox nails it when he says Chip was producing books at different points in his life and Chip has always put himself into his books whether they were early SF, criticism, or memoir. And I’d agree that Chip isn’t cranking out spaceships or nuclear-ravaged earths the way the early works could seem—but I also swear that the ideas have been evolving since the beginning. I remember one of the earlier ones, Einstein maybe, where the chapter started with Chip quoting someone he’d talked to that week, citing it as a comment to the author. That level of intertextuality or interstitiality speaks to so much of what Chip has accomplished since then.

Nick Mamatas

Nick Mamatas

As it turns out, people don’t like porn that isn’t for them. Further, most SF readers are pretty much at sea if they don’t have any tropes to think about. A straightforward and beautiful realist novel like Dark Reflections is just perplexing because it’s just about some guy living his life. No way!

I actually prefer his porn to his SF for the most part. It’s difficult to write transgressive, dirty, occasionally simply wrong stuff with such sympathy and warmth, but Delany manages it. He is an utterly unique writer in th

I actually prefer his porn to his SF for the most part. It’s difficult to write transgressive, dirty, occasionally simply wrong stuff with such sympathy and warmth, but Delany manages it. He is an utterly unique writer in th

0 Comments on Samuel R. Delany: Another Roundtable as of 3/24/2014 1:47:00 PM

Add a Comment