new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: What Killed it For Me, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 6 of 6

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: What Killed it For Me in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

Looking back at the posts in this series, I’m starting to get a complex about being wayyyyy too picky with my reading. Thankfully, I’m running out of reasons why I stop reading books, so I’m going to finish this series with a final post on why readers might stop reading your book. It’s a blessing and a curse: Personal Preference.

Basically, no matter how well written your books are, certain people will never read them because they’re not the kind of books that they like to read. It’s really that simple.

I’m sure it’s delicious. But I don’t like tea.

Here’s an example: I remember starting a book that had everything a good book is supposed to have: solid writing, likable characters, high stakes. It was a dystopian set in a future where there were no trees. Interesting premise, yes? I thought so. The lack of trees made for an arid, dusty, sterile-feeling environment, and the author did a masterful job of drawing that. But here’s the thing: as a reader, I’m kind of weird in that the setting is hugely important for me. I like settings that are rich and thick and textured—places I would like to visit or even live. This was not one of those places. The story was good, but I just wasn’t feeling it because I couldn’t totally buy into the setting.

Let me reiterate: nothing wrong with the book. It just happened to go against one of my personal preferences.

Here’s another example: Recently, I picked up two different books by favorite authors of mine. I was primed to really like both of these books, but I didn’t make it all the way through because they were written in a genre I don’t normally like to read. I was hoping that my love of their writing would get me past the genre, but it didn’t. That is all.

Other Books That Pretty Much Everyone Liked Except Me: The DaVinci Code. The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo. The Hunt for Red October. All great books. Couldn’t get into them. Why? I don’t know. They just weren’t my thing.

Unfortunately, there’s nothing we can do to fix this particular problem, because it’s not actually a problem—not like the other reasons we’ve discussed in this series. There isn’t something you’ve done wrong or need to change. Some people simply aren’t going to like your book, no matter how great it is. And there’s precious little you can do about it.

What you CAN do is 1) accept that some people just aren’t going to like your stuff, and 2) write for the people who get you. Also, study the craft. Practice, practice, practice, so you can put out a quality product that won’t contain the gaffes we’ve discussed in this series and cause your eager audience to toss your book aside within the first twenty pages.

And for the love of all that’s chocolate, if you review books often, please don’t pan a book because it wasn’t your cup of tea. Angela and I have run into this a few times, where we were given a bad review because the reader didn’t understand what our book was supposed to be about. If there’s something wrong with a story, by all means, let the review reflect it. But don’t discourage other readers from picking up a book simply because it’s not the kind that you prefer to read.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this series. I’ve learned a lot by figuring out why certain books didn’t work for me. Here’s hoping that we can put these ideas into practice so our readers keep reading, page after page after page.

*photo credit: Kai Schreiber @ Creative Commons

The post What Killed It For Me #8: Personal Preferences appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS.

I started this series talking about issues in books that pretty much everyone can agree are a problem: weak writing, clichéd characters, unclear character goals, etc. Last week’s post on Action Openings was a little more subjective, and today’s pet peeve is going to be more so. It has to do with sequels and why I may finish the first book but not read any of the rest.

I started this series talking about issues in books that pretty much everyone can agree are a problem: weak writing, clichéd characters, unclear character goals, etc. Last week’s post on Action Openings was a little more subjective, and today’s pet peeve is going to be more so. It has to do with sequels and why I may finish the first book but not read any of the rest.

First let me say that I’ve never written a series. All of my books so far have been stand-alones (though I’ll eventually be turning one into the first of a series). So I don’t have any experience writing a series. But I’ve read a TON of them and, as a reader, I have strong opinions about what works and what doesn’t. You may agree, you may want to stab me with your voodoo pins. Either way, here are the reasons why, in the past, I’ve finished book one of a sequel but failed to read any of the rest:

Courtesy: Raymond Bryson @ Creative Commons

1) Too Many Unanswered Questions. I recently read a paranormal thriller that had me RIVETED. It involved a killer on the loose, a tropical island, a curious weather pattern, a mysterious clique of fascinating but ominous people, and frequent vanishings. The stakes were clearly high, the characters interesting, the premise fabulous, and I was completely invested right up to the end. Then I finished the book. I slammed it shut, held it up for my husband to see, and made some form of unkind declarative statement that I won’t repeat here.

A lot of questions were raised in this book, and I think maybe two of them were answered by the end. The rest…well, you’ll just have to read the sequel to find out. Um, no. I was so confused (and pissed) when I finished, that I won’t be reading any of the sequels.

As authors, we have an obligation to our readers to deliver what we promise. If you give readers an indication that the hero’s eventually going to have a show down with the villain, you need to fulfill that promise and make sure it happens. In the same way, if you raise a bunch of important plot-based questions, the reader expects those important questions to be explained. Now, I’m not saying that everything has to be ironed out by the end of the first book. Far from it. But you have to answer enough of the questions so the first book makes sense on its own. Every book, even one in a series, needs a complete story arc. So please, for the love of all things literary, if you’re going to write a series, answer the pertinent questions at the end of the first book. Don’t be coy and mysterious and assume that readers will be intrigued by your ambiguity. No, they’ll just be annoyed. Let’s try to avoid that.

2) Too much elapsed time between books. I read a really popular first book in a series a few years ago. The second one came out in the fall; I put it on my reading list, and there it sits. Six months later. Still unread. I really liked the first book. I gave it four stars on Goodreads—high praise from me. I recommended it to friends when I was finished. But a year-and-a-half later, I just wasn’t into it any more. Now, the books that I absolutely LOVE, it won’t matter how much time goes by before the next book is released: the Daughter of Smoke and Bone series, the Grisha trilogy, The Wicked and the Just (please please PLEASE, when is the sequel coming???). I snapped up (will snap up) these sequels as soon as they’re available. But, to be fair, these kind of LOVE books are few and far between for me. I may like a first book—I may really really like it—but if too much time passes before the next book in the series, I could very well lose interest and never another of those books.

So here’s my first suggestion for avoiding this, and please bear with me, because I know this isn’t possible for everyone: If it’s possible for you as an author, self-publish your series. This way, you can control the timeline and release your books at intervals that will keep readers salivating.

Now, I realize that this may not be possible if you’re working with a publisher. Readers may have to wait a year to eighteen months before seeing your next book and you may not be able to do anything about that. So here are two suggestions that may help tide readers over from one book to the next:

- Before the second/third/etc. book comes out, publish a summary of the previous books on your website. Sometimes, I find out a second book has come out, but I’m not really interested because so much time has elapsed that I can’t remember what happened in the first book. But if there’s a summary for the first book out there, I read it, and I remember why I liked that book. I get jazzed again and many times end up continuing the series.

- If possible, micro-publish related pieces in the interim. If your readers will have a while to wait between books, provide some related material that will give them a taste of your world/characters/story between releases. Write a novella from a minor character’s perspective (à la the supplements to Susan Kaye Quinn’s Mindjack series). Provide a short story that explains an important event from your hero’s or villain’s past. Now, I don’t know what limitations traditionally published authors might have in this area (maybe someone could chime in on this?), but your interim pieces don’t have to be books for sale. Post them to your blog and let everyone read them. Save them in PDF format and make them available for free download at your website. Send them to your newsletter subscribers. This is a great way to keep readers interested in your series during a long interim between releases.

As a reader, I love me a good series. Right now, I’m on book two of The Last Apprentice, which has apparently been out forever and WHY DIDN’T ANYONE TELL ME? As a writer, sadly, I’ve got few personal words of wisdom to share. But that’s what friends are for, right? Janice Hardy’s got 7 tips for you on writing a series and Joanna Penn has some great advice on avoiding continuation issues when writing a series. Jami Gold’s started an interesting discussion on if you should even learn how to write one. And then there’s Holly Lisle, who I wish was my friend, offering a video-series workshop on How to Write a Series. Enjoy!

The post What Killed It For Me, #7: Issues with Sequels appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS.

This looks like a good place to start my story…

It’s likely that we’ve all encountered these stories—the ones that open with an explosion, plague, car chase, alien abduction, fist fight, or other volatile scene involving a main character that we know virtually nothing about. I get why authors do this. It makes sense that starting the story with a bang would engage readers and suck them right in. But most of the time, the opposite happens for me: I end up confused and uninterested. And here’s why: To care about what’s happening to the character, I have to first care about the character.

To care about a hero, readers need to know what he wants and what’s at stake if he doesn’t get it. They’ve also got to respond to him emotionally on a certain level if they’re going to empathize with him and his circumstances. Readers need to have a feel for this stuff before the main character gets thrown into the arena or accused of espionage. If the cart comes before the horse here, it’s highly likely that readers won’t engage and may not continue reading.

So how do we avoid this problem in our own writing?

1. Don’t start with the main action. We need to see the character in her real world before the main conflict arises. This provides contrast, pitting the old safe-but-somehow-unsatisfactory world against the crazy new one. It also gives us a chance to get to know the hero before her world is turned upside down. So if your story is about people surviving an ebola outbreak, don’t open with the hero’s mother bleeding from the eyes. If it’s about a woman living in the aftermath of divorce, don’t open with her husband leaving her. Give readers a chance to care about the hero before the main conflict arises, and readers will be more inclined to stick around to see what happens to her.

2. Avoid gimmicky opening action sequences. I made this mistake in one of my first novels. My book opened with the main character running through a field, breathing heavily and casting frantic looks over her shoulder. Readers assumed she was being chased, and she was. But when it turned out she was just playing hide-and-seek, they were not amused. The opening came across as contrived, which is fitting, since that’s exactly what it was. Readers are smart. They know when they’re being deceived or manhandled, and like anyone with any sense, they don’t like it at all. (This is one of the reasons why opening dream sequences rarely work.)

The thing is, enthralling stories that suck readers in don’t have to start with action. Look at The Hunger Games. Talk about action-packed—yet, it opens with the main character waking up. Collins could have opened her book at half-a-dozen later points in the story, and there would have been a lot more going on. But those openings wouldn’t have worked, imo, because they weren’t the right place to start her story. And that brings us to something super important that you have to do…

3. Start your story in the right place. I’ve heard it said that you should start your story just before the protagonist’s life intersects with the antagonist’s agenda. The Hunger Games is a great example. President Snow’s agenda is to strengthen his control over the people of Panem via the hunger games. Katniss has been to the reaping a number of times, but because her name hasn’t been called, her life hasn’t yet intersected with Snow’s agenda. That doesn’t happen until Prim’s name is picked. Had Collins started the story after that, the opening would have been jarring and probably confusing for readers. Had she started much earlier than she did, the opening would have dragged.

Finding the right starting point is critically important in engaging readers early. Locate that magical point where the antagonist’s agenda intersects with the hero’s life. Open your story just before that collision, and you’ll likely be starting in a spot that will resonate with readers.

Photo credit: The Official CTBTO Photostream @ Creative Commons

The post What Killed it For Me #6: Action Too Early appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS.

Courtesy of Tom Newby @ Creative Commons

It’s hard to come up with characters who are believable yet don’t sound like every other character out there. It’s especially easy to fall into this trap with certain archetypes, like witty sidekicks or wise old mentors. Unfortunately, a recent book that I started had a whole cast of clichés: the jaded, super-sarcastic teen girl hero; the loving but confused single parent; a villain in the form of a Queen Bee Mean Girl. As for the love interest and sidekick…I didn’t stick around long enough to meet them.

But even one clichéd character may be too much; you don’t want to give readers a reason to lose interest or roll their eyes when they’re introduced to a character they’ve seen a dozen times. Character creation is one of our passions at Writers Helping Writers, thanks to the research and practice we put in while writing our negative trait and positive trait thesaurus books. Here are some tips we’ve learned on how to write believable and interesting characters without repeating the stereotypes:

Explore the character’s backstory to discover her wounds. It’s easy to throw together a bunch of attributes and flaws when creating characters. But traits develop organically out a combination of factors: upbringing, environment, basic needs, morals, past wounds, personal values, etc. It is this unique combination of elements that results in a truly unique character. To avoid recreating a character who already exists, delve deeply into her backstory. Doing so will give you the information you need to figure out exactly who she is today.

Once you’ve explored the character’s backstory, use that information to choose a combination a flaws and attributes that make sense, but are unique. For example, it makes sense for a character who was once the victim of a home invasion to be over-protective and paranoid. For me, the mention of those flaws instantly brings to mind an image—a stereotype that I’ve seen a million times. Paranoia is a logical result of this kind of traumatizing experience, but what if you combined it with other flaws or attributes to turn the stereotype on its ear? Maybe your character was raised in a very proper household where any kind of emotional extreme was taboo. So now you’ve got a genteel, mannerly character who’s scared of her own shadow—but has to hide her fears out of a desire to maintain the right image.

Creating unique characters is really just a matter of digging into their history and coming up with traits that make sense for them. For help in this area, we created a number of related resources on our Tools for Writers page, including the Reverse Backstory Tool, the Attribute Target Tool, and the Character Pyramid Tool.

Explore the positive side of negative traits, and vice versa. Clichéd characters are seen as clichés because they’re easy to read. They’re cardboard. One-dimensional. Which is ironic because character traits are anything but.

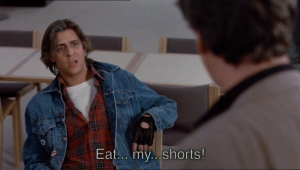

Courtesy of Adg’s Screen Caps @ Creative Commons

Look at John Bender, from the movie The Breakfast Club. He’s hostile, and embodies many of the expected negative associations that go with that trait: he’s volatile, verbally abusive, and has trouble connecting with others. But hostility also has some positive aspects that John exhibits. He’s fearless and uninhibited, often saying what other people are too timid to say themselves. The positive sides of this flaw make him more than just an angry character. They make him interesting and somewhat endearing because people value fearlessness and admire those who speak their minds. We want to evoke those endearing feelings in our readers, so make sure to explore both sides of your character’s defining traits and you’re sure to come up with someone unique and compelling.

Don’t forget the quirks and idiosyncrasies. Certain character types—like adventure heroes and detectives—easily fall into stereotypes. If you want your hero to be different, give him something interesting that will make him stand out from the crowd. Indiana Jones? Afraid of snakes. Captain Jack Sparrow is a cowardly pirate. And for those of you who remember Kojak, what comes to mind when you hear that name? Bald guys and lollipops, right? Mission accomplished.

A word of caution regarding quirks, though: if they’re thrown in off-handedly, they can feel clumsy and contrived. Find something that makes sense for your character based on his backstory and personality and you’ll have something that is believable rather than gimmicky.

Add an inner goal. Another reason detectives and adventurers tend to resemble each other is because they all have the same goal: to find the treasure or solve the case. But what if your character also has an internal goal—something he needs to overcome or wants to achieve that will result in personal growth?

In The Bone Collector, Lincoln Rhyme is an ex-forensics specialist on the trail of a serial killer in New York City. This is his outer goal: to find the killer. Just like any other detective story, eh? Except that Lincoln Rhyme is a paraplegic. That’s enough to make him interesting, but there’s more: it’s made clear from the beginning of the story that the thing Rhyme wants more than anything is to die. He’s made plans for his “final transition” and is seemingly at peace with it because he thinks this will make him more happy and fulfilled.

By adding an internal goal, Deaver adds a dimension to his main character that makes him different from other detectives. Keep this in mind for your own heroes. For more information internal goals and motivations, check out Michael Hauge’s Writing Screenplays That Sell.

Character creation is tricky, but with a little extra backstory digging and these tips, there’s no limit to the number of unique and resonant characters that we can create. Happy writing!

The post What Killed It For Me #4: Clichéd Characters appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS.

Happy spring everyone! Those of you who live up north, please don’t hurt me. To be honest, there’s really no difference in the weather between spring and winter where I live, so it shouldn’t be such a big deal to me. But last week was Spring Break—my first real one in years. When I had kids at home, people would be all Woohoo! It’s Spring Break! And I was all Really? Then why are my kids still waking me up at 6:30? But my daughter is in kindergarten now, and last week, we did get get to sleep in, and go bowling and to the beach and to the park and to every fast food restaurant in town—all without any real schedule to speak of. It. Was. AWESOME.

So, happy Spring, everyone! If you haven’t seen it yet, it’s coming, I promise :).

And now, for the latest book I gave up on. This one was a fantasy and there were like five books in the series, so I figured it would probably be good. And it was very promising. But it was also very confusing. Set in a make believe world, it was based on a unique and fantastical element, contained an involved political hierarchy, a main character who didn’t know who he was or where he’d come from, and two separate point-of-view characters whose stories seemed to be unrelated.

Now, because fantasy is by far my favorite genre to read, I’m used to magical elements and complicated caste systems and too many characters. But this one was just too much. As I read it, my brain was trying to figure out the political system, and where the hero fit into it, and who he really was, and how the magical element worked. And what was with the second narrator? Where did she fit in?

CollegeDegrees360 @ Creative Commons

I see this problem sometimes with fantasy and sci-fi. I write mostly fantasy, and I have this problem myself. The author tries to make things so unique that the reader has to focus too much on assimilating new information and she can’t enjoy the story. But there are ways to introduce a whole new world—even one that needs explanation—in a way that won’t confuse readers.

City of a Thousand Dolls is a book that does this very well. In this story, there’s a rigid social/political caste system, a school for abandoned girls with its own separate hierarchy, talking cats, and shape-shifting characters who can turn into different animals. This story could easily be confusing and off-putting. Instead, it’s deeply engaging with an incredibly strong sense of place. Here are some ways that Miriam Forster introduces her fantasy world without overwhelming readers:

1. Introduce new elements slowly. It takes awhile for readers to assimilate new information. If you throw too much at them at once, their brains can’t keep up and they either shut down and quit reading or they miss important information that will cause confusion later. Space out the introduction of new information so readers aren’t overwhelmed. Don’t try to jam it all into the first chapter.

2. When possible, show unique elements instead of telling them. Many fantasy writers make the mistake of stopping the story to explain some of the unknown bits. This kind of telling, especially at the beginning of a story, should be avoided because a) it drags the story to a halt while the author stops to explain stuff, and b) it further slows the reader’s progress because she’ll have to pause later on to assimilate the given information into the current story. Instead of telling or explaining new elements, introduce them through the context of the current story.

One of the unique elements in City of a Thousand Dolls is something called an asar. To show what it is, Forster references it in context, and the reader is able to figure it out without even slowing down: Her satisfaction lasted only as along as it took for a group of girls to decide she was an easy target in her plain gray asar and untidy braid. And a few paragraphs later: She could imagine the House Mistress perfectly, her rust-brown asar wrapped so it came only to her knees, the short sword at her side. With these two context clues, the reader gets an adequate idea of what an asar is without having to interrupt the story to figure it out. When it comes to fantastical elements, show whenever you can.

Thomas Guest @ Creative Commons

3. Don’t Reinvent the Wheel. As a fantasy author, I know our tendency to go a little crazy with the world building. We’re so into our new world and its uniqueness that we come up with new inventions and new names for everything. But too much of this becomes tiring for readers. If you have a unique element, make sure it’s necessary. Forster’s asars play an important part in the story because they designate which house each girl belongs to. Through this article of clothing, she avoids having to identify each girl’s house when the girls are introduced. So think carefully before coming up with a new form of lighting, time telling, transportation, or messenger service. Keep the unique components that add to your story and stick with what already works for the rest. (For more tips on creating a believable setting, see this post on World Building Rules and Elements).

4. Simplify. Sometimes it’s not just the cool elements that we tend to overdo. It’s the plot line, setting, family history, political structure, etc. In many cases, these things can be simplified without taking anything away from the story. To see if your overall story has got too much going on, summarize it. If you can do so succinctly and listeners aren’t confused, then you should be able to write it in a way that readers will understand. If you share your summary and listeners have to ask questions to clarify, you either haven’t summarized it well or you’ve got too much going on. See what can be removed or pared back so the amazingness of your story can shine through instead of being overwhelmed. An added benefit of summarizing your plot line or setting is that it shows you what’s important. Whatever’s included in your summary should be introduced and clarified first. Then you can move on to the other stuff.

So, have you read any other-worldly books that were fully believable? What techniques did the author use to make the whole thing work? And if you missed the first two posts in this series, you can find them here and here.

The post What Killed It For Me #3: Too Much Going On appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS.

For my first post in this series, I focused on a common reason that readers might stop reading: Lack of a Clear Goal. If the main character doesn’t have a goal, or if it’s not revealed early on, readers don’t know where the story’s headed and may end up losing interest.

Today, I’m going to talk about a problem I ran into just last week. I was browsing the library shelves and came across a book I’d never read by one of my favorite authors when I was a teen. It was a companion novel to a series I’d devoured—the paperbacks are literally falling apart on my bookshelf at home. Needless to say, before I’d read a single word, I was fully prepped to love this book.

Sadly, I didn’t.

The main character was mentioned in the original series but never made an appearance. Now I know why. He was surly, incredibly cocky, apathetic to the feelings of others, mean to a homeless dog that kept turning up, and had a chip on his shoulder the size of Texas. Granted, he had a good reason for being so crabby. This, combined with my desire to love the story, kept me reading far longer than I normally would have. But by chapter four, I gave it up.

Courtesy of Inkox @ Creative commons

Character creation is tricky. Our heroes have to have flaws, but they can’t be so flawed that people would rather abandon them than share the journey. A book that achieves this balance flawlessly is one of my favorite reads of 2013: The Wicked and the Just. The story is incredibly well-written, but I also love it because it contains the most unlikable character I think I’ve ever read. And yet I cared about what happened to her. I not only finished the book, I now haunt the author’s website looking for the sequel. When I deconstruct Coats’ writing, I see some techniques she utilized to make her unlikable character not only bearable, but endearing:

High Stakes. The year is 1293, and Cecily’s father is moving them to occupied Wales, where tensions between the ruling English and subdued Welsh are high. It’s clear from the beginning that serious trouble is coming and Cecily will be smack in the middle of it. Though a character may be unlikable, readers can still empathize with her if her circumstances are dire. That danger doesn’t have to be physical, though. Circumstances that threaten a character’s emotional or mental wellbeing can be just as gripping. Look at John Nash from A Beautiful Mind. Whatever’s at stake, make sure it’s big and it’s clear, and readers may still root for an unlikable character.

Endearing Traits. Certain character traits are nearly universally admired by others: intelligence, wit or humor, feistiness. Cecily’s voice conveys all of these things. Though she’s selfish, manipulative, and sometimes mean, you’re drawn in because she’s funny, and though you don’t approve of her methods, you have to admire her for striving so hard for what she wants. To make a difficult character more palatable, give her some likable qualities, and readers just might buy in.

An Endearing Moment. Though Cecily’s admirable qualities are evident in her narrative, I don’t think that an entertaining voice is enough. Coats remedies this on page four by including a brief conversation between Cecily and two friends that reveals how brokenhearted they all are that Cecily is leaving. Though her good qualities are understated, the affection of her friends shows that someone truly likes her—that she’s worth liking. It’s downplayed, but it’s a classic Save The Cat moment. Show your character doing something likable or being likable in some way, and the reader will see that she’s not a lost cause.

One caveat: I’ve always believed that the main character has to be likable in some way for readers to make that magical connection. But after thinking on this for awhile, I think I’ve changed my tune. I mean, Scarlett O’Hara wasn’t likable at all. Will Hunting: not exactly a charmer. But these characters resonate with audiences. Why? Because they evoke an emotion that endears them somehow to audiences: they make them laugh, or elicit admiration, or evoke sympathy.

So if you’ve got a character that’s hard to love, utilize one or more of these techniques to draw out those endearing emotions, and you just might ensure that readers will keep on reading.

The post What Killed it for Me #2: Characters Who Aren’t Endearing appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS.