Eleanora E. Tate’s eyes glimmer with the twinkle of a teacher. She passes along wisdom with a heap of humor and grace. That’s a quality of her acclaimed stories too. Author of 11 books, Tate celebrates neighborhoods, families and communities with plots that move and challenge and characters who endure long after her stories end.

She first felt the pull to write in her Missouri hometown. It was a pursuit that called to Tate as a girl and became a mission as she entered adulthood. Tate has been a journalist, owner with her husband, photographer Zack E. Hamlett, III, of a public relations firm and president of the National Association of Black Storytellers, Inc. Her commitment to writing stories that explore the African-American experience has remained steadfast.

More than an award-winning author, Tate is a warrior. She fights for authentic images of African-Americans in children’s literature. Research is a hallmark of her work. She’s a children’s book writer, folklorist, teacher, wife, mother and mentor. We’re proud to feature Eleanora E. Tate on the seventh day of our campaign.

In the bio on your web site, you share that you wrote your first “book” in sixth grade. How did that experience and others in your childhood put you on the path to publication?

My book, at 30 (actually 15 8 1/2 x 11 folded in half) pages long, was comparable to War and Peace in my mind! I’ve always loved words. Some words sounded so juicy when they rolled off my tongue that I could taste them, like “salacious.”

The first short story I can remember writing was when I was in third grade in my hometown of Canton, Missouri. So the “book” was the next step up. My book a couple of years later got me in trouble with my junior high school girls’ advisor in Des Moines, Iowa. She felt some of the language and certainly the scenes were, well, promiscuous. She was right. That proved to me how powerful the written word was. I think I used the word “salacious” in it, too.

What inspired you to write for children? How has your career as a journalist informed your children’s writing?

I came of age writing poetry and stories for adults in Des Moines in the mid-1960s during the Black Power movement (yes, there ARE Black people in Iowa). When I was a teenager my poems were sometimes published in The Iowa Bystander, the local African American weekly newspaper where I later worked as news editor. Being “published” brought attention to my work. I also wrote stories and poems for my junior high and high school newspapers. My first poem was published nationally in a student magazine. From the time I could write, my aim was to be published. I thought being a published writer would be the coolest thing in the world. I loved the works of Gwendolyn Brooks, who was a mentor; James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry, Joyce Carol Oats, Virginia Hamilton, Frenchie Hodges, Frances E. W. Harper, Audre Lorde — so many wonderful writers!

I came of age writing poetry and stories for adults in Des Moines in the mid-1960s during the Black Power movement (yes, there ARE Black people in Iowa). When I was a teenager my poems were sometimes published in The Iowa Bystander, the local African American weekly newspaper where I later worked as news editor. Being “published” brought attention to my work. I also wrote stories and poems for my junior high and high school newspapers. My first poem was published nationally in a student magazine. From the time I could write, my aim was to be published. I thought being a published writer would be the coolest thing in the world. I loved the works of Gwendolyn Brooks, who was a mentor; James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry, Joyce Carol Oats, Virginia Hamilton, Frenchie Hodges, Frances E. W. Harper, Audre Lorde — so many wonderful writers!

As an adult, my friends and I connected with Black Power. Huey Newton sitting in that peacock chair with his rifle hung on a poster on my wall in my apartment. We actually had a chartered Black Panther Party in Des Moines, founded by Charles Knox, who was from Chicago.

As part of our own Black Arts Community in Des Moines we artists held poetry readings, Black art exhibitions with fiery plays and speeches in the local parks, in schools, at community centers, and in the streets. I read my poetry, with a flutist and drummer accompanying me. Periodically I held poetry parties in my home.

My poems were about Black strengths, Black Power, the importance of Black unity. I wrote lots of stories for adults but I couldn’t get them sold. In 1969, a year after Dr. martin Luther King, Jr. was murdered, a memorial was held for him in Des Moines, and I was asked to read my “King” poem. I did. I think something like 3,000 people were in the audience, and remains the largest audience I’ve ever spoken to.

My poems were about Black strengths, Black Power, the importance of Black unity. I wrote lots of stories for adults but I couldn’t get them sold. In 1969, a year after Dr. martin Luther King, Jr. was murdered, a memorial was held for him in Des Moines, and I was asked to read my “King” poem. I did. I think something like 3,000 people were in the audience, and remains the largest audience I’ve ever spoken to.

But my stories for adults weren’t getting published. When I became a member of the Iowa Arts Council’s Writers in the Schools program in 1970, I began to share poems I’d written about my childhood. I also entered the Irma S. Black (an extraordinary senior editor) children’s short story competition for Bankstreet College of Education in New York. I didn’t win the contest, but Mrs. Black took a personal interest in my work. She published my story — now known as “An Ounce of Sand” in the textbook Impossible? (Houghton-Mifflin, 1972). William Hooks, now a well known children’s book author living in Chapel Hill, was one of my editors there.

When I realized there was a niche for children’s stories — particularly those featuring African American children and written by African Americans — I turned my literary sights in that direction. I write all this to say it was more my taking advantage of a literary opportunity to get published over anything else. Being a reporter also now for The Des Moines Tribune (part of The Des Moines Register and Tribune chain at that time) I was getting feature stories published anyway. But these children’s stories would be mine.

If you could go back and whisper in your ear when you were just starting out, what advice would you give yourself about the children’s book industry?

“Eleanora, as you dream about being a published writer, dream about making lots of money, too.” I didn’t think about money when I started out, because probably like most of us in those days, we just wanted to get published. The pittance we received for sales of short stories — and all rights — were secondary. But I must admit I had a wake-up call when I began to really do my homework about the business of writing and the rights of writers. I learned early on that aspiring writers must know about contracts and copyrights and royalties. I probably got a boost in learning about that because I worked for a newspaper and that kind of information was fairly common knowledge. And as controversial as it might sound, the other bit of information I would whisper to myself is, “editors will be white most of the time.”

“Eleanora, as you dream about being a published writer, dream about making lots of money, too.” I didn’t think about money when I started out, because probably like most of us in those days, we just wanted to get published. The pittance we received for sales of short stories — and all rights — were secondary. But I must admit I had a wake-up call when I began to really do my homework about the business of writing and the rights of writers. I learned early on that aspiring writers must know about contracts and copyrights and royalties. I probably got a boost in learning about that because I worked for a newspaper and that kind of information was fairly common knowledge. And as controversial as it might sound, the other bit of information I would whisper to myself is, “editors will be white most of the time.”

Having come of age in the 1960s and being pro-Black, I was aware of this. I was not aware at that time of the battles I would have when it came to retaining African American cultural content in my manuscripts.

There are not many more African American authors of children’s books now than there were in 1980 when my first book, Just an Overnight Guest, was published. We just die off, get replaced, and the cycle continues. As a gross number more African American children’s book authors have been published, but many more white authors of books about African American children are getting published, too. I caution aspiring Black authors not to accept just anything to get published, not to let their work be marginalized, and to learn about African American history. Just being an African American doesn’t automatically make the writer an authority of the culture. All writers need to do research to make a work ring true. And, just because an editor says that a situation is what she says it is/was in African American history doesn’t mean that she’s right.

My gains? Well, I have eleven — all of my books. I’m proud of them all. My future? To be able to sit down in a sun-drenched corner and rest from time to time, and then to write without disturbance, and to fish.

What were some of the toughest obstacles you encountered when you began your children’s book career? What were some of your proudest moments?

That’s tough. One editor and I had battles over every chapter. One of my books takes place in 1904. My main character lives in a lower middle-class, rural Black family. My editor insisted that my main character should wear “plaits.” I maintained that as a member of a striving Black family the mother would never let her daughters wear “plaits.” I’d started out writing that she wore “French braided” hair. Editor said that was not in fashion in 1904, and substituted “plaits.” Well, that did it. We compromised with corn rows, I think. Another time she said my main character’s father would not have a rolltop desk in his home, believing that the father would be illiterate and have no need for a rolltop desk. I maintained that my main character could read and write, sat there to read his newspaper and to write out bills. Another time an art editor wanted to place a horrifying picture of a Black man hanging in the afterward of my fiction book to illustrate the horror. I refused. When I’ve had to deal with this kind of editorial arrogance on an editor’s part, I’ve simply said, “Go on and publish it but take my name off the book.” That has caused senior editors to step in and support me.

That’s tough. One editor and I had battles over every chapter. One of my books takes place in 1904. My main character lives in a lower middle-class, rural Black family. My editor insisted that my main character should wear “plaits.” I maintained that as a member of a striving Black family the mother would never let her daughters wear “plaits.” I’d started out writing that she wore “French braided” hair. Editor said that was not in fashion in 1904, and substituted “plaits.” Well, that did it. We compromised with corn rows, I think. Another time she said my main character’s father would not have a rolltop desk in his home, believing that the father would be illiterate and have no need for a rolltop desk. I maintained that my main character could read and write, sat there to read his newspaper and to write out bills. Another time an art editor wanted to place a horrifying picture of a Black man hanging in the afterward of my fiction book to illustrate the horror. I refused. When I’ve had to deal with this kind of editorial arrogance on an editor’s part, I’ve simply said, “Go on and publish it but take my name off the book.” That has caused senior editors to step in and support me.

It’s not rare these days to hear about children’s books being made into movies. But when your book, Just An Overnight Guest, was made into an award-winning film starring Richard Roundtree and Rosalind Cash, that was less common. Please tell us about your experience.

I think we need to qualify whose children’s books are made into movies and whose are not. We aren’t hearing about books written by African American authors being made into movies these days — Indian in the Cupboard, Harry Potter, the Lemony Snicket books, Bridge to Teribethea(sp) — these are not books by Black authors. I cannot think of many books by Black authors being made into movies. Evelyn Coleman’s “White Socks Only;” Mildred Tayor’s “Roll of Thunder Hear My Cry;” my “Just an Overnight Guest” — I think they are few and far between. Barbara Bryant is the producer of Coleman’s and my films, and she is an African American. There aren’t many like her in the field, so I am truly blessed.

Your latest novel, Celeste’s Harlem Renaissance (Little, Brown, 2007) earned wonderful reviews and recently won the 2007 North Carolina Book Award for Juvenile Literature. Congratulations! How do you measure your success? How important are awards and recognition to you?

I think everyone likes to be recognized for their work. Celeste’s Harlem Renaissance received the 2007 North Carolina Book Award-American Association of University Women Award for Juvenile Literature and I am truly honored. Awards for me are few and far between, too. That’s why being one of the Brown Bookshelf’s authors means to much to me. It’s very difficult to break through. My books have a certain amount of notoriety because I deal bluntly and I hope honestly with the African American experience as I perceive it, and I don’t let whites off the hook.

I think everyone likes to be recognized for their work. Celeste’s Harlem Renaissance received the 2007 North Carolina Book Award-American Association of University Women Award for Juvenile Literature and I am truly honored. Awards for me are few and far between, too. That’s why being one of the Brown Bookshelf’s authors means to much to me. It’s very difficult to break through. My books have a certain amount of notoriety because I deal bluntly and I hope honestly with the African American experience as I perceive it, and I don’t let whites off the hook.

One blogger felt the number of well-known African Americans in Celeste’s Harlem Renaissance was unrealistic. What she and others do not realize is that in 1921 most of these persons were not well known at all. In addition it wasn’t unusual for prominent African Americans to rub elbows in a few special places during segregated times and in socially segregated facilities. Some reviewers and bloggers forgot or never knew that New York and Harlem, NY, where part of my book takes place, was still very much segregated, though not as overtly as North Carolina. Small realities like that still hamper white reviewers’ perceptions and color their very public opinions, which can hurt a book. One reviewer who was critical of Celeste was from Kansas. Uh … would she truly be knowledgeable about 1921 Harlem and segregation?

I recall a conversation I had some years back with the late, wonderful Dr. James Haskins, known as the Dean of Black Biographies. He was my editor for my book African American Musicians in his Black Stars biographies. He told me when he was working on a piece about the Scottsboro Boys an editor he’d submitted the manuscript to returned it, saying it couldn’t have happened. This is just one instance of editorial arrogance and editorial ignorance that we must be ever vigilant about.

Please tell us about your Carolina Trilogy. What was the inspiration?

I write about my Carolina Trilogy in my scholarly piece “Tracing the Trilogy” in African American Review (Spring 1998; Dr. Diane Johnson Feelings, Editor). My wonderful editor Jean Vestal would cross out chunks of The Secret of Gumbo Grove and remind me that ” ‘you can’t put the whole history of Black America into this one book, Eleanora. You’re telling the story of just one little girl.’ Jeanne was right. What I had to tell wouldn’t fit into one book.” (p. 77) After The Secret of Gumbo Grove (Watts, 1987) came Thank You, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.! (Watts, 1990) and A Blessing in Disguise (Delecorte, 1995; reprinted, Just Us Books, 1999). All three are still in print, or they were this morning.

I write about my Carolina Trilogy in my scholarly piece “Tracing the Trilogy” in African American Review (Spring 1998; Dr. Diane Johnson Feelings, Editor). My wonderful editor Jean Vestal would cross out chunks of The Secret of Gumbo Grove and remind me that ” ‘you can’t put the whole history of Black America into this one book, Eleanora. You’re telling the story of just one little girl.’ Jeanne was right. What I had to tell wouldn’t fit into one book.” (p. 77) After The Secret of Gumbo Grove (Watts, 1987) came Thank You, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.! (Watts, 1990) and A Blessing in Disguise (Delecorte, 1995; reprinted, Just Us Books, 1999). All three are still in print, or they were this morning.

It wasn’t until I had finished Gumbo Grove that I felt the need to place two more books along the coast of South Carolina in mythical Calvary County. I write about neighborhoods and communities and families not written about before by an African American author, and from the viewpoint of an African American child. I personally believe there’s a difference in the authenticity of books written by someone from within the culture and books written by someone from without. I’ll accept that anyone has a right to write about any ethnicity/culture he/she wants, but not everybody from outside that culture does it well. Not everybody does it well from the inside, either, but over the long run you do it better.

It wasn’t until I had finished Gumbo Grove that I felt the need to place two more books along the coast of South Carolina in mythical Calvary County. I write about neighborhoods and communities and families not written about before by an African American author, and from the viewpoint of an African American child. I personally believe there’s a difference in the authenticity of books written by someone from within the culture and books written by someone from without. I’ll accept that anyone has a right to write about any ethnicity/culture he/she wants, but not everybody from outside that culture does it well. Not everybody does it well from the inside, either, but over the long run you do it better.

In 1978, when I began writing The Secret of Gumbo Grove, I couldn’t find quality fiction books about contemporary South Carolina African American children, and certainly none that took place in Horry and Georgetown Counties. I couldn’t find children who could tell me names of people they thought were famous in Horry County, either. Gumbo Grove involves an intellectually curious girl who searches for her community’s and an old cemetery’s history and in the end makes herself and the residents prouder of who they are in the process. It’s based on an actual experience. Gumbo Grove was published on the cusp of very pivotal times in Horry and Georgetown Counties, and people embraced it. The search for identity resonates in all communities, I think, so it received national acclaim. The whole language movement in which books were used across the curriculum was sweeping the country at that time, and Gumbo Grove served as just the right literary vehicle.

Thank You, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.! involved pride of who you are, intra-racial color consciousness — always very real in the Black community — and finding a sense of place in one’s home. Those are touching subjects that go to the heart of our families. A Blessing in Disguise was based on what I saw around me in Myrtle Beach, SC, where we lived from 1978 to 1992, when crack cocaine began devastating our neighorborhoods. I think we were living in the middle of it, and it seemed that the police, the politicians and the preachers looked the other away, as long as drug money was being put in the collection plates.

Thank You, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.! involved pride of who you are, intra-racial color consciousness — always very real in the Black community — and finding a sense of place in one’s home. Those are touching subjects that go to the heart of our families. A Blessing in Disguise was based on what I saw around me in Myrtle Beach, SC, where we lived from 1978 to 1992, when crack cocaine began devastating our neighorborhoods. I think we were living in the middle of it, and it seemed that the police, the politicians and the preachers looked the other away, as long as drug money was being put in the collection plates.

These three books cover from 1978 to 1995, a volatile period in our country’s history. I don’t write just for art’s sake. I write to reveal, to resonate, to reconnect, and to renourish. As a writer — period — I want my books — whether historical fiction, fiction, biography, even my humorous books – to have messages, no matter what the experts say about “didactic,” and I hope that readers old and young get messages and hope from them.

I’ll leave this world still an old writing warrior, cane in the air, on a rant, probably still writing. And fishing.

The Buzz on Celeste’s Harlem Renaissance:

Winner, 2007 North Carolina Book Award for Juvenile Literature (AAUW)

Celeste ” begins a coming-of-age journey that encompasses physical and emotional maturity, as well as a greater understanding of the people who touch her life — in essence, her own Harlem Renaissance . . . Tate has an eye, and an ear, for the ambience of the era as it is reflected in both the strictly segregated South and the new ideas emanating from Harlem.

Celeste and her friends and family are well-conceived individuals, both real and imagined, and represent the wide variety of characters and personalites of African-American Society without reverting to stereotypes. Absorbing.”

– Kirkus Reviews

” . . . readers will connect with her strong, regional voice . . . Both sobering and inspiring, Tate’s novel is a moving portrait of growing up black and female in 1920s America.”

– Booklist

“In Celeste, Tate has created a fully realized heroine, whose world expands profoundly as she’s exposed to both the cultural pinnacles and racial prejudices of her era. Readers will likely happily accompany Celeste on her journey.”

– Publishers Weekly

Tate “draws her characters with charming humor and multidimensional candor . . . fans of historical fiction will stick with Celeste, eager to see her true blossoming at the end.”

– School Library Journal

Tate’s “. . . large ensemble of secondary characters is complex, distinctive and well developed. Celeste’s wide-eyed observations, organic to her strong but somewhat sheltered character, pull readers into the thrills and fears of her rapidly expanding world.”

– Horn Book Magazine

Books by Eleanora E. Tate:

Celeste’s Harlem Renaissance

Just An Overnight Guest

The Secret of Gumbo Grove

Front Porch Stories at the One-Room School

Thank You, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.!

Retold African Myths

The Minstrel’s Melody

A Blessing in Disguise

African American Musicians

Don’t Split the Pole: Tales of Down-Home Wisdom

To Be Free

To learn more about Eleanora E. Tate, please visit: www.eleanoraetate.com.

You can also check out the following articles:

http://aalbc.com/authors/eleanora.htm

http://www.randomhouse.com/teens/authors/author.pperl?authorid=30607

http://biography.jrank.org/pages/2939/Tate-Eleanora-E.html

(Credit for Tate photo: Zack E. Hamlett, III)

I still remember the third grade where I was a student at John Dewey Elementary School - my teacher Mrs. Kaveney, recess, hundreds of games of kickball, our Black History Month program, the school spelling bee, the end of the year class picnic at Mrs. Kaveney’s house. Thanks to Valerie Wilson Wesley’s Willimena Rules’ series, I was able to go back to the third grade at Harriet Tubman Elementary School. But instead of Mrs. Kaveney, Willimena was taught by Mrs. Sweetly who is rumored to be a mean teacher.

I still remember the third grade where I was a student at John Dewey Elementary School - my teacher Mrs. Kaveney, recess, hundreds of games of kickball, our Black History Month program, the school spelling bee, the end of the year class picnic at Mrs. Kaveney’s house. Thanks to Valerie Wilson Wesley’s Willimena Rules’ series, I was able to go back to the third grade at Harriet Tubman Elementary School. But instead of Mrs. Kaveney, Willimena was taught by Mrs. Sweetly who is rumored to be a mean teacher. up reading

up reading  spends her cookie money, loses a coveted role in the school play, worries about Valentine’s Day and is intimidated by a class bully. My favorite of the six titles was How to Lose Your Cookie Money. In this book Willie is a Girl Scout who spends part of the money raised selling Girl Scout cookies on something else and needs to recover that money in a hurry. I could relate to this story because I was a Girl Scout too and throughout school, I had to sell candy. Every now and then, I would eat the merchandise myself and have to come up with the money because I was sort of irresponsible. But Willie did a much better thing with the money than I did.

spends her cookie money, loses a coveted role in the school play, worries about Valentine’s Day and is intimidated by a class bully. My favorite of the six titles was How to Lose Your Cookie Money. In this book Willie is a Girl Scout who spends part of the money raised selling Girl Scout cookies on something else and needs to recover that money in a hurry. I could relate to this story because I was a Girl Scout too and throughout school, I had to sell candy. Every now and then, I would eat the merchandise myself and have to come up with the money because I was sort of irresponsible. But Willie did a much better thing with the money than I did.

I know that you have two daughters. How much of Willimena and Tina are based on your daughters?

I know that you have two daughters. How much of Willimena and Tina are based on your daughters? Harriet Tubman as her model of strength and perseverance. Who are people that you admire from history?

Harriet Tubman as her model of strength and perseverance. Who are people that you admire from history? What is your writing atmosphere like? Are you an early in the morning or late at night writer? Do you need absolute quiet or is there music playing in the background?

What is your writing atmosphere like? Are you an early in the morning or late at night writer? Do you need absolute quiet or is there music playing in the background?

Celise Downs was born, and currently makes her home, in Phoenix, AZ. Her love of writing began in the 7th grade as a way to dispel recess boredom. Her talent was further encouraged by a high school English teacher. She considers her novels to be about the high school experience with a dash of intrigue.

Celise Downs was born, and currently makes her home, in Phoenix, AZ. Her love of writing began in the 7th grade as a way to dispel recess boredom. Her talent was further encouraged by a high school English teacher. She considers her novels to be about the high school experience with a dash of intrigue. In Dance Jam Productions, Mataya Black Hawk is hiding a very dark secret from her friends. Are there any issues that you feel are “taboo” in young adult fiction?

In Dance Jam Productions, Mataya Black Hawk is hiding a very dark secret from her friends. Are there any issues that you feel are “taboo” in young adult fiction? There are very few African-American authors that write contemporary fiction from the point of view of a character that isn’t African-American, yet you did this with Skylar Knight, the protagonist of Secrets and Kisses. Can you talk a little about why you chose to create this character as you did?

There are very few African-American authors that write contemporary fiction from the point of view of a character that isn’t African-American, yet you did this with Skylar Knight, the protagonist of Secrets and Kisses. Can you talk a little about why you chose to create this character as you did?

Reading about Coe Booth’s journey to becoming a published writer is inspirational. Having read many of her

Reading about Coe Booth’s journey to becoming a published writer is inspirational. Having read many of her  I read in another article that you are working on the sequel to Tyrell and you’re bombarded with questions and ideas for how that should go. Don’t you just love when your readers respond to your story and characters in that way? How is the sequel going for you? Is Tyrell speaking to you or through you like he did the first time?

I read in another article that you are working on the sequel to Tyrell and you’re bombarded with questions and ideas for how that should go. Don’t you just love when your readers respond to your story and characters in that way? How is the sequel going for you? Is Tyrell speaking to you or through you like he did the first time?

A teacher’s classroom is always abuzz with activity from the students and teacher engaged in learning. I can only imagine the level of buzz in author Karen English’s classroom. As she works with her students and listens to them, the wheels in her mind are turning as she creates stories from what she sees and hears. Karen English is in tune to the stories that her students hunger for and feeds that need through her own writing which is also inspired by a piece of artwork or a childhood memory.

A teacher’s classroom is always abuzz with activity from the students and teacher engaged in learning. I can only imagine the level of buzz in author Karen English’s classroom. As she works with her students and listens to them, the wheels in her mind are turning as she creates stories from what she sees and hears. Karen English is in tune to the stories that her students hunger for and feeds that need through her own writing which is also inspired by a piece of artwork or a childhood memory. Scott King Honor Award

Scott King Honor Award KE: Everyday life is really what most of our African American children live. If we respect their emotional lives we can see that they don’t need to be set apart. Emotionally human beings are the same. I’d like to see more stories driven by the everyday than by events. I think our children would more readily see themselves. Books would be more high interest and we wouldn’t lose so many to TV and video games.

KE: Everyday life is really what most of our African American children live. If we respect their emotional lives we can see that they don’t need to be set apart. Emotionally human beings are the same. I’d like to see more stories driven by the everyday than by events. I think our children would more readily see themselves. Books would be more high interest and we wouldn’t lose so many to TV and video games. realized we can only blame ourselves. There’s so much that needs to be told. There’s enough for all writers and perhaps I shouldn’t be so proprietary. After all, I wrote about a little Pakistani girl in Nadia’s Hands and little Hispanic girl in Speak English for Us, Marisol.

realized we can only blame ourselves. There’s so much that needs to be told. There’s enough for all writers and perhaps I shouldn’t be so proprietary. After all, I wrote about a little Pakistani girl in Nadia’s Hands and little Hispanic girl in Speak English for Us, Marisol. As a teacher, what books are your students reading? What are they most interested in reading? Do their interests play a part in the books you’ve written?

As a teacher, what books are your students reading? What are they most interested in reading? Do their interests play a part in the books you’ve written? KE: I love Allen Say (illustrator), Kevin Henkes (picture book writer)… Their work taps into universal emotions.

KE: I love Allen Say (illustrator), Kevin Henkes (picture book writer)… Their work taps into universal emotions.

Called to writing as a child, award-winning author Carole Boston Weatherford wrote her first poem in grade school. When her father, a printing teacher, printed several of her poems, Weatherford received a special thrill. Little did she know she held the future in her hands.

Called to writing as a child, award-winning author Carole Boston Weatherford wrote her first poem in grade school. When her father, a printing teacher, printed several of her poems, Weatherford received a special thrill. Little did she know she held the future in her hands.  That poem about the four seasons alerted my parents to my gift. My mother wrote down that first poem and later asked my father, a high school printing teacher, to have his students print a few of my poems on the letterpress in his classroom. So, in second grade, I saw my work in print. That was a rare treat in the days before desktop computers and laser printers.

That poem about the four seasons alerted my parents to my gift. My mother wrote down that first poem and later asked my father, a high school printing teacher, to have his students print a few of my poems on the letterpress in his classroom. So, in second grade, I saw my work in print. That was a rare treat in the days before desktop computers and laser printers. I want my books to nudge young readers toward justice. I want children to celebrate African American culture, while at the same time acknowledging the most shameful chapters of our nation’s past-slavery and segregation. I hope that my young readers understand that freedom was not free and that people of conscience must speak their minds and live their values.

I want my books to nudge young readers toward justice. I want children to celebrate African American culture, while at the same time acknowledging the most shameful chapters of our nation’s past-slavery and segregation. I hope that my young readers understand that freedom was not free and that people of conscience must speak their minds and live their values. The biggest mountain was getting editors to read my work and to regard my subjects as more than so-called “footnotes to history.” Before black authors can enlighten and inspire young readers, we must educate those editors who assume that if they themselves are not aware, then the topic is not important or not universal.

The biggest mountain was getting editors to read my work and to regard my subjects as more than so-called “footnotes to history.” Before black authors can enlighten and inspire young readers, we must educate those editors who assume that if they themselves are not aware, then the topic is not important or not universal. Regardless of how my books are marketed or reviewed, most of what I write is poetry. It’s not merely lyrical text; it’s poetry, dear reader. Notable exceptions are Freedom on the Menu: The Greensboro Sit-ins (Dial, 2004); Champions on the Bench (Dial, 2006); and Sink or Swim: African American Lifesavers of the Outer Banks (Coastal Carolina Press, 1999).

Regardless of how my books are marketed or reviewed, most of what I write is poetry. It’s not merely lyrical text; it’s poetry, dear reader. Notable exceptions are Freedom on the Menu: The Greensboro Sit-ins (Dial, 2004); Champions on the Bench (Dial, 2006); and Sink or Swim: African American Lifesavers of the Outer Banks (Coastal Carolina Press, 1999). pilgrimage into my past. At archives, I pored over prints and photographs to pair with original poems. Eventually, I was no longer looking for images to illustrate poems but writing poems for pictures that begged for words. Paired with my poems, those images form a metaphorical bridge spanning 400 years of African American history. When that book debuted, I put a period on that phase of my life. I turned the page and began a quest for new chapters. Several poems from Remember the Bridge have been anthologized in textbooks.

pilgrimage into my past. At archives, I pored over prints and photographs to pair with original poems. Eventually, I was no longer looking for images to illustrate poems but writing poems for pictures that begged for words. Paired with my poems, those images form a metaphorical bridge spanning 400 years of African American history. When that book debuted, I put a period on that phase of my life. I turned the page and began a quest for new chapters. Several poems from Remember the Bridge have been anthologized in textbooks. Here is a snapshot of my formative years in the 1960s. My father’s jazz collection was the soundtrack. I lived in libraries, but found few books featuring children of color. But the all-black faculty at my all-black inner city elementary school gave us regular doses of black history. Not just in February but all school year. At that school, I was introduced to the poetry of Langston Hughes. His words fell on my ears like a song I longed to hear. My parents and grandmothers also shared stories about the color line. And, of course, the Civil Rights Movement was ushering change. That foundation made me want to know even more about my people, even more about the past.

Here is a snapshot of my formative years in the 1960s. My father’s jazz collection was the soundtrack. I lived in libraries, but found few books featuring children of color. But the all-black faculty at my all-black inner city elementary school gave us regular doses of black history. Not just in February but all school year. At that school, I was introduced to the poetry of Langston Hughes. His words fell on my ears like a song I longed to hear. My parents and grandmothers also shared stories about the color line. And, of course, the Civil Rights Movement was ushering change. That foundation made me want to know even more about my people, even more about the past. It’s hard to believe that I’ve been publishing since 1995 when there was somewhat of a multicultural boom. I am proud of the progress made and prizes won by those black authors and illustrators who are still in the game. But when I peruse publishers’ catalogs now, I see fewer books about black subject matter and even fewer by black authors. Like our people’s voices, our books get marginalized, ghettoized. Thus, many of our stories are doomed to obscurity. Of course, I wish the tide would turn, but I’m not sure if or when it will, especially in a celebrity-driven publishing market.

It’s hard to believe that I’ve been publishing since 1995 when there was somewhat of a multicultural boom. I am proud of the progress made and prizes won by those black authors and illustrators who are still in the game. But when I peruse publishers’ catalogs now, I see fewer books about black subject matter and even fewer by black authors. Like our people’s voices, our books get marginalized, ghettoized. Thus, many of our stories are doomed to obscurity. Of course, I wish the tide would turn, but I’m not sure if or when it will, especially in a celebrity-driven publishing market.  Before John Was a Jazz Giant: A Song of John Coltrane (Henry Holt & Co., 2008), illustrated by Sean Qualls, will be released by Henry Holt in April. And I am eagerly anticipating the September release of Becoming Billie Holiday (Wordsong, 2008), a fictional verse memoir illlustrated by Floyd Cooper and my first young adult title, by Wordsong/Boyds Mills Press. Billie Holiday is my muse; so I have a lot riding on that book.

Before John Was a Jazz Giant: A Song of John Coltrane (Henry Holt & Co., 2008), illustrated by Sean Qualls, will be released by Henry Holt in April. And I am eagerly anticipating the September release of Becoming Billie Holiday (Wordsong, 2008), a fictional verse memoir illlustrated by Floyd Cooper and my first young adult title, by Wordsong/Boyds Mills Press. Billie Holiday is my muse; so I have a lot riding on that book.

I was tickled the other day, following the Grammy music awards. The discussion: Beyoncé’s introduction of Tina Turner as “the queen.” It caused quite a stir. At least with

I was tickled the other day, following the Grammy music awards. The discussion: Beyoncé’s introduction of Tina Turner as “the queen.” It caused quite a stir. At least with  More recently, her work was recognized by the

More recently, her work was recognized by the  Eloise: My primary mission remains the same. Although the situation is not now as desperate as it once was, there is still a need for more children’s books that document our existence and depict African Americans living, as we do in real life, a variety of lifestyles. I’d like to see this body of literature continue to grow, and I want to contribute to it. From time to time, I will also write books that fit within a broader context. My most recent book,

Eloise: My primary mission remains the same. Although the situation is not now as desperate as it once was, there is still a need for more children’s books that document our existence and depict African Americans living, as we do in real life, a variety of lifestyles. I’d like to see this body of literature continue to grow, and I want to contribute to it. From time to time, I will also write books that fit within a broader context. My most recent book,  Don: I am primarily an illustrator. I didn’t consider myself a word person until just a few years ago when I began writing myself. But I struggle with words, and often, I am struck with writer’s block. What are your struggles and how do you overcome them?

Don: I am primarily an illustrator. I didn’t consider myself a word person until just a few years ago when I began writing myself. But I struggle with words, and often, I am struck with writer’s block. What are your struggles and how do you overcome them? Don: In terms of developing your writing, what was the best decisions you’ve made?

Don: In terms of developing your writing, what was the best decisions you’ve made? Don: In bringing a story to life, what are some of the challenges you face?

Don: In bringing a story to life, what are some of the challenges you face? Don: You are a successful author and speaker. And you have a family. How do you find balance — and writing time, for that matter?

Don: You are a successful author and speaker. And you have a family. How do you find balance — and writing time, for that matter?

Growing up, Tonya Bolden thought one day she would be a teacher. Today, as an award-winning author of more than 20 books for young people and adults, she is just that. Her classroom has no walls. Instead, you just need to pick up one her acclaimed books on topics such as the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., George Washington Carver or Reconstruction to step into the world she creates. History, she has said, is her passion. She passes that rich knowledge of the past on to people around the world.

Growing up, Tonya Bolden thought one day she would be a teacher. Today, as an award-winning author of more than 20 books for young people and adults, she is just that. Her classroom has no walls. Instead, you just need to pick up one her acclaimed books on topics such as the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., George Washington Carver or Reconstruction to step into the world she creates. History, she has said, is her passion. She passes that rich knowledge of the past on to people around the world. It landed me might be a better way to put it. Marie Brown, my agent at the time, pitched me to Vy Higginsen and to Scholastic for working with Vy on turning her gospel musical Mama, I Want to Sing into a young adult novel. After that book was done, the editor talked about my doing another book for her. Result: And Not Afraid to Dare: The Stories of Ten African-American Women (Scholastic Press, 1998). So writing for the young found me and I found myself loving it more and more, but never thinking I couldn’t also do books for adults.

It landed me might be a better way to put it. Marie Brown, my agent at the time, pitched me to Vy Higginsen and to Scholastic for working with Vy on turning her gospel musical Mama, I Want to Sing into a young adult novel. After that book was done, the editor talked about my doing another book for her. Result: And Not Afraid to Dare: The Stories of Ten African-American Women (Scholastic Press, 1998). So writing for the young found me and I found myself loving it more and more, but never thinking I couldn’t also do books for adults. Some ideas spring from my curiosity. Others represent some unfinished business. (Example: the little bit I was taught in school about Reconstruction left me feeling bad about black folks. Thus, my book Cause: Reconstruction America (Knopf, 2005). Sometimes an editor comes to me with an idea. With The Champ (Knopf, 2004), illustrator Greg Christie was very keen on doing a book about Ali. I was very keen on working with Greg again after the art he created for Rock of Ages: A Tribute to the Black Church (Random House, 2001). At the outset, I really wasn’t all that passionate about Ali, but, oh, how that changed after I did the research and discovered for myself why he was “the greatest” and thought, He was no mere boxer; he was an artist!

Some ideas spring from my curiosity. Others represent some unfinished business. (Example: the little bit I was taught in school about Reconstruction left me feeling bad about black folks. Thus, my book Cause: Reconstruction America (Knopf, 2005). Sometimes an editor comes to me with an idea. With The Champ (Knopf, 2004), illustrator Greg Christie was very keen on doing a book about Ali. I was very keen on working with Greg again after the art he created for Rock of Ages: A Tribute to the Black Church (Random House, 2001). At the outset, I really wasn’t all that passionate about Ali, but, oh, how that changed after I did the research and discovered for myself why he was “the greatest” and thought, He was no mere boxer; he was an artist! I doubt 20-something-year-old me would listen to 40-somethng-year old me. Also, I agree with Soren Kierkegaard that “Life can only be understood backwards but must be lived forwards,” and with Sigourney Weaver that “the crooked path has its dividends.”

I doubt 20-something-year-old me would listen to 40-somethng-year old me. Also, I agree with Soren Kierkegaard that “Life can only be understood backwards but must be lived forwards,” and with Sigourney Weaver that “the crooked path has its dividends.” Receiving a letter from a girl or boy telling me that she or he was moved by or learned something from one of my books.

Receiving a letter from a girl or boy telling me that she or he was moved by or learned something from one of my books.  What inspires your work?

What inspires your work? Last thing: I think we must acknowledge that part of the reason many young people feel history is irrelevant is because most adults feel the same way.

Last thing: I think we must acknowledge that part of the reason many young people feel history is irrelevant is because most adults feel the same way.

Not one to limit himself to strictly novels, Myers has also excelled at both short stories and poetry. His novel

Not one to limit himself to strictly novels, Myers has also excelled at both short stories and poetry. His novel  in verse,

in verse,  KLIATT gave Game a starred review, saying, “Myers…clearly knows basketball, and he nails the court action… A great choice for sports fans.” School Library Journal adds, “As always, Myers eschews easy answers, and readers are left with the question of whether or not Drew is prepared to deal with the challenges that life will inevitably hand him.”

KLIATT gave Game a starred review, saying, “Myers…clearly knows basketball, and he nails the court action… A great choice for sports fans.” School Library Journal adds, “As always, Myers eschews easy answers, and readers are left with the question of whether or not Drew is prepared to deal with the challenges that life will inevitably hand him.”

Much like the revered Langston Hughes, Allison Whittenberg is also an author, poet, and playwright. An admirer of Gwendolyn Brooks, Tennessee Williams, Richard Wright, Katherine Mansfield, Dorothy Parker, and Albert Camus, Allison knew early in life that she wanted to be a writer. As the author of Sweet Thang and

Much like the revered Langston Hughes, Allison Whittenberg is also an author, poet, and playwright. An admirer of Gwendolyn Brooks, Tennessee Williams, Richard Wright, Katherine Mansfield, Dorothy Parker, and Albert Camus, Allison knew early in life that she wanted to be a writer. As the author of Sweet Thang and  AW: Sweet Thang was loosely based on my recollections and observations growing up in West Philly until I was in second grade and there after, the first tier, predominately African American suburb of Yeadon, PA (which in the book I call Dardon). I wanted to show the type of intact, largely wholesome Black family that myself and most of my friends grew up in. Most importantly, in Sweet Thang, Charmaine fiercely misses her Auntie Karyn. I channeled the deep loss I felt regarding my mother’s passing during my mother’s years. I was proud to dedicate the book to her.

AW: Sweet Thang was loosely based on my recollections and observations growing up in West Philly until I was in second grade and there after, the first tier, predominately African American suburb of Yeadon, PA (which in the book I call Dardon). I wanted to show the type of intact, largely wholesome Black family that myself and most of my friends grew up in. Most importantly, in Sweet Thang, Charmaine fiercely misses her Auntie Karyn. I channeled the deep loss I felt regarding my mother’s passing during my mother’s years. I was proud to dedicate the book to her. March 11th will be an exciting day for you as your second novel hits the bookshelves. What was it like writing Life is Fine versus writing Sweet Thang?

March 11th will be an exciting day for you as your second novel hits the bookshelves. What was it like writing Life is Fine versus writing Sweet Thang?

For the longest time, whenever anyone mentioned “Science Fiction Author” and “African-American” in the same sentence, the only author that came to mind was the late, great

For the longest time, whenever anyone mentioned “Science Fiction Author” and “African-American” in the same sentence, the only author that came to mind was the late, great  Varian: Congratulations on your recent selection as a finalist for the 2008 Essence Magazine Literary Award for Children’s Books, the Andre Norton Award, and NAACP Image Award. If you could use only three words to describe your nominated title, The Shadow Speaker, what would you use?

Varian: Congratulations on your recent selection as a finalist for the 2008 Essence Magazine Literary Award for Children’s Books, the Andre Norton Award, and NAACP Image Award. If you could use only three words to describe your nominated title, The Shadow Speaker, what would you use? I didn’t set out to write The Shadow Speaker and Zahrah the Windseeker specially as YA novels. I didn’t set out to write them as fantasy with elements of science fiction. I just wrote them and they happened to have teenage main characters and magical, sometimes science-based, things just happened. I’ve written adult fiction, YA fiction, mainstream realistic fiction, magical realism, fantasy, science fiction, memoir, screenplays, scripts for plays, journalistic essays, book reviews, and scholarly papers.

I didn’t set out to write The Shadow Speaker and Zahrah the Windseeker specially as YA novels. I didn’t set out to write them as fantasy with elements of science fiction. I just wrote them and they happened to have teenage main characters and magical, sometimes science-based, things just happened. I’ve written adult fiction, YA fiction, mainstream realistic fiction, magical realism, fantasy, science fiction, memoir, screenplays, scripts for plays, journalistic essays, book reviews, and scholarly papers.

Typically, when you think of an author/illustrator, you think of someone who combines words with paintings or drawings to tell a story. But author/illustrator Nina Crews is not your typical storyteller — she’s extraordinary, and chooses to illustrate her stories with photographs. “I fell in love with photography in college,” she says. “While I studied painting, drawing and sculpture, I felt that I could make my strongest work with photography. When I started writing books, I never seriously considered making more ‘traditional’ illustrations. I was a photographer and so my books would be photographic.”

Typically, when you think of an author/illustrator, you think of someone who combines words with paintings or drawings to tell a story. But author/illustrator Nina Crews is not your typical storyteller — she’s extraordinary, and chooses to illustrate her stories with photographs. “I fell in love with photography in college,” she says. “While I studied painting, drawing and sculpture, I felt that I could make my strongest work with photography. When I started writing books, I never seriously considered making more ‘traditional’ illustrations. I was a photographer and so my books would be photographic.” In her most recent book, Below (Henry Holt & Company, 2006), a young child rescues Guy, an action-figure that has fallen through a hole in the stairs, from imagined dangers from below. With this book, Ms. Crews successfully combined color and black and white photographs with line drawings. This handsome book is colorful and friendly — fun, not only for the child, but mom and dad, too.

In her most recent book, Below (Henry Holt & Company, 2006), a young child rescues Guy, an action-figure that has fallen through a hole in the stairs, from imagined dangers from below. With this book, Ms. Crews successfully combined color and black and white photographs with line drawings. This handsome book is colorful and friendly — fun, not only for the child, but mom and dad, too. Can you tell us about your road to publication, the highs and lows?

Can you tell us about your road to publication, the highs and lows?

h. Fresh from college, Jabari Asim sold TVs at a Sears in St. Louis and dreamed big dreams. When his first poem was published in Black American Literature Forum, that was all he needed to set him on his path. He left that job and took the leap of faith that led him to a successful journalism career with the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, The Washington Post and now his leading role as editor of the NAACP’s historic magazine, The Crisis. It brought him to children’s books too.

h. Fresh from college, Jabari Asim sold TVs at a Sears in St. Louis and dreamed big dreams. When his first poem was published in Black American Literature Forum, that was all he needed to set him on his path. He left that job and took the leap of faith that led him to a successful journalism career with the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, The Washington Post and now his leading role as editor of the NAACP’s historic magazine, The Crisis. It brought him to children’s books too. I was always inspired by Langston Hughes, whose career suggested that you had a better chance of actually earning a living as a writer if you showed a willingness to be proficient in as many genres as possible. Earning a living was important because I always had babies to feed. But all of the writing, regardless of genre, has always been informed and motivated by my life as a husband and father. I try to write books that will entertain, inform or stimulate my children. That goes for my books for adult as well: I hope that my children will eventually read them and find them useful.

I was always inspired by Langston Hughes, whose career suggested that you had a better chance of actually earning a living as a writer if you showed a willingness to be proficient in as many genres as possible. Earning a living was important because I always had babies to feed. But all of the writing, regardless of genre, has always been informed and motivated by my life as a husband and father. I try to write books that will entertain, inform or stimulate my children. That goes for my books for adult as well: I hope that my children will eventually read them and find them useful. I was approached to write a middle-school novel about the Reconstruction after my friend Fred McKissack Jr. recommended me to the publisher. I wrote a couple sample chapters and an outline and they gave me the green light to finish it. It’s called The Road to Freedom (Glencoe/McGraw-Hill, 2001) and tells the story of a father and son in the early days following Emancipation. It has managed to have legs, and I’m grateful for that.

I was approached to write a middle-school novel about the Reconstruction after my friend Fred McKissack Jr. recommended me to the publisher. I wrote a couple sample chapters and an outline and they gave me the green light to finish it. It’s called The Road to Freedom (Glencoe/McGraw-Hill, 2001) and tells the story of a father and son in the early days following Emancipation. It has managed to have legs, and I’m grateful for that. Despite the noteworthy successes of some of our best-known African American children’s book authors, our foothold remains fragile. With a few laudable exceptions, we remain dependent on the whims and limited knowledge of publishing staffs that seldom look like us or know much about us. It’s an industry that remains largely, inexcusably monochromatic. My editors have, for the most part, been people of color, and their presence is living testimony that we have made some gains. At the same time, there are losses. As I write this, the area where I live has been deeply affected by the demise of the Karibu bookstore chain. On more than one occasion, event planners at Karibu paired me with Mocha Moms, an organization that has been wonderfully supportive to me and other writers like me. Few chain bookstores would have the interest or community knowledge to create and sustain those kinds of alliances. We are similarly dependent on events such as the multicultural children’s book fair at the Kennedy Center in Washington, and the African-American Children’s Book Fair run by Vanesse Lloyd-Sgambati in Philadelphia. These kinds of community-based events and institutions exist outside of the industry and are of inestimable value.

Despite the noteworthy successes of some of our best-known African American children’s book authors, our foothold remains fragile. With a few laudable exceptions, we remain dependent on the whims and limited knowledge of publishing staffs that seldom look like us or know much about us. It’s an industry that remains largely, inexcusably monochromatic. My editors have, for the most part, been people of color, and their presence is living testimony that we have made some gains. At the same time, there are losses. As I write this, the area where I live has been deeply affected by the demise of the Karibu bookstore chain. On more than one occasion, event planners at Karibu paired me with Mocha Moms, an organization that has been wonderfully supportive to me and other writers like me. Few chain bookstores would have the interest or community knowledge to create and sustain those kinds of alliances. We are similarly dependent on events such as the multicultural children’s book fair at the Kennedy Center in Washington, and the African-American Children’s Book Fair run by Vanesse Lloyd-Sgambati in Philadelphia. These kinds of community-based events and institutions exist outside of the industry and are of inestimable value. Absolutely. Poetry was my concentration in college, and I’ve been fortunate to have work included in several African American anthologies. I think I’d love rhyme even if I didn’t have that background, however, and my fondness for it had much to do with the creation of those two books.

Absolutely. Poetry was my concentration in college, and I’ve been fortunate to have work included in several African American anthologies. I think I’d love rhyme even if I didn’t have that background, however, and my fondness for it had much to do with the creation of those two books.

Chosen by NPR as a Novel You Wish a Teacher Would Assign, M. Sindy Felin’s debut novel Touching Snow is an amazing story to read. I literally devoured Karina’s story in two days.

Chosen by NPR as a Novel You Wish a Teacher Would Assign, M. Sindy Felin’s debut novel Touching Snow is an amazing story to read. I literally devoured Karina’s story in two days.  “The best way to avoid being picked on by high school bullies is to kill someone.” The opening sentence of Touching Snow lets you know this is no ordinary story and hooks you to find out what happens that the protagonist is forced to kill someone. In a

“The best way to avoid being picked on by high school bullies is to kill someone.” The opening sentence of Touching Snow lets you know this is no ordinary story and hooks you to find out what happens that the protagonist is forced to kill someone. In a

Patricia C. McKissack’s journey to become a children’s book author began as she sat on the front porch wrapped in her mother’s arms. As she listened to her mama recite the poetry of Paul Laurence Dunbar, a spell wove around them. Words and possibility swirled in the air until bedtime called and poetry danced in McKissack’s dreams.

Patricia C. McKissack’s journey to become a children’s book author began as she sat on the front porch wrapped in her mother’s arms. As she listened to her mama recite the poetry of Paul Laurence Dunbar, a spell wove around them. Words and possibility swirled in the air until bedtime called and poetry danced in McKissack’s dreams. That commitment to filling in the missing pieces of America’s story marks McKissack’s career as a children’s book author. Her award-winning stories have helped change the face of children’s literature. Author of more than 100 books, McKissack is as prolific and she is passionate. She draws on memories — listening to spooky stories and tall tales spun by elders on the front porch. She explores the past, bringing to life gems of African-American history. When asked why she writes, McKissack answers “to tell a different story — one that has been marginalized by mainstream history; one that has been distorted, misrepresented or just plain forgotten.”

That commitment to filling in the missing pieces of America’s story marks McKissack’s career as a children’s book author. Her award-winning stories have helped change the face of children’s literature. Author of more than 100 books, McKissack is as prolific and she is passionate. She draws on memories — listening to spooky stories and tall tales spun by elders on the front porch. She explores the past, bringing to life gems of African-American history. When asked why she writes, McKissack answers “to tell a different story — one that has been marginalized by mainstream history; one that has been distorted, misrepresented or just plain forgotten.” What inspired you to write for children?

What inspired you to write for children?

It has been a while since I’ve been in the classroom, yet I feel like a teacher. There will always be a bit of the teacher in me. For example, successful teachers don’t talk down to their students; they don’t tell students how to think, and finally they don’t hit students over the head with a MESSAGE! The same applies to a writer. Being preachy is the kiss of death for any book. And every writer should put a sign over his/her workplace: “Show don’t tell.”

It has been a while since I’ve been in the classroom, yet I feel like a teacher. There will always be a bit of the teacher in me. For example, successful teachers don’t talk down to their students; they don’t tell students how to think, and finally they don’t hit students over the head with a MESSAGE! The same applies to a writer. Being preachy is the kiss of death for any book. And every writer should put a sign over his/her workplace: “Show don’t tell.”

Getting letters from children who say they never enjoyed reading until they read one of my books. Now that’s heady stuff. Of course winning a Newbery Honor, Coretta Scott King, NAACP Image Award, etc. are memorable moments - especially when (at the NAACP Image Award) Terry McMillan introduced me to her son as “Messy Bessey’s Mama.”

Getting letters from children who say they never enjoyed reading until they read one of my books. Now that’s heady stuff. Of course winning a Newbery Honor, Coretta Scott King, NAACP Image Award, etc. are memorable moments - especially when (at the NAACP Image Award) Terry McMillan introduced me to her son as “Messy Bessey’s Mama.” We appreciate the awards. In terms of sales an award sticker can make a big difference, and also give a book longevity. But children’s book writers don’t get to sell directly to their market. There is an adult who buys for the child. So, when I get a letter from a young reader that is the best reward I can get.

We appreciate the awards. In terms of sales an award sticker can make a big difference, and also give a book longevity. But children’s book writers don’t get to sell directly to their market. There is an adult who buys for the child. So, when I get a letter from a young reader that is the best reward I can get. Writers write. They don’t spend time talking about what they want to write one day…when…after…etc.. Get busy and write, then begin market your work. Writing is a demanding business. It requires attention.

Writers write. They don’t spend time talking about what they want to write one day…when…after…etc.. Get busy and write, then begin market your work. Writing is a demanding business. It requires attention.

I came of age writing poetry and stories for adults in Des Moines in the mid-1960s during the Black Power movement (yes, there ARE Black people in Iowa). When I was a teenager my poems were sometimes published in The Iowa Bystander, the local African American weekly newspaper where I later worked as news editor. Being “published” brought attention to my work. I also wrote stories and poems for my junior high and high school newspapers. My first poem was published nationally in a student magazine. From the time I could write, my aim was to be published. I thought being a published writer would be the coolest thing in the world. I loved the works of Gwendolyn Brooks, who was a mentor; James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry, Joyce Carol Oats, Virginia Hamilton, Frenchie Hodges, Frances E. W. Harper, Audre Lorde — so many wonderful writers!

I came of age writing poetry and stories for adults in Des Moines in the mid-1960s during the Black Power movement (yes, there ARE Black people in Iowa). When I was a teenager my poems were sometimes published in The Iowa Bystander, the local African American weekly newspaper where I later worked as news editor. Being “published” brought attention to my work. I also wrote stories and poems for my junior high and high school newspapers. My first poem was published nationally in a student magazine. From the time I could write, my aim was to be published. I thought being a published writer would be the coolest thing in the world. I loved the works of Gwendolyn Brooks, who was a mentor; James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry, Joyce Carol Oats, Virginia Hamilton, Frenchie Hodges, Frances E. W. Harper, Audre Lorde — so many wonderful writers! My poems were about Black strengths, Black Power, the importance of Black unity. I wrote lots of stories for adults but I couldn’t get them sold. In 1969, a year after Dr. martin Luther King, Jr. was murdered, a memorial was held for him in Des Moines, and I was asked to read my “King” poem. I did. I think something like 3,000 people were in the audience, and remains the largest audience I’ve ever spoken to.

My poems were about Black strengths, Black Power, the importance of Black unity. I wrote lots of stories for adults but I couldn’t get them sold. In 1969, a year after Dr. martin Luther King, Jr. was murdered, a memorial was held for him in Des Moines, and I was asked to read my “King” poem. I did. I think something like 3,000 people were in the audience, and remains the largest audience I’ve ever spoken to. “Eleanora, as you dream about being a published writer, dream about making lots of money, too.” I didn’t think about money when I started out, because probably like most of us in those days, we just wanted to get published. The pittance we received for sales of short stories — and all rights — were secondary. But I must admit I had a wake-up call when I began to really do my homework about the business of writing and the rights of writers. I learned early on that aspiring writers must know about contracts and copyrights and royalties. I probably got a boost in learning about that because I worked for a newspaper and that kind of information was fairly common knowledge. And as controversial as it might sound, the other bit of information I would whisper to myself is, “editors will be white most of the time.”

“Eleanora, as you dream about being a published writer, dream about making lots of money, too.” I didn’t think about money when I started out, because probably like most of us in those days, we just wanted to get published. The pittance we received for sales of short stories — and all rights — were secondary. But I must admit I had a wake-up call when I began to really do my homework about the business of writing and the rights of writers. I learned early on that aspiring writers must know about contracts and copyrights and royalties. I probably got a boost in learning about that because I worked for a newspaper and that kind of information was fairly common knowledge. And as controversial as it might sound, the other bit of information I would whisper to myself is, “editors will be white most of the time.” That’s tough. One editor and I had battles over every chapter. One of my books takes place in 1904. My main character lives in a lower middle-class, rural Black family. My editor insisted that my main character should wear “plaits.” I maintained that as a member of a striving Black family the mother would never let her daughters wear “plaits.” I’d started out writing that she wore “French braided” hair. Editor said that was not in fashion in 1904, and substituted “plaits.” Well, that did it. We compromised with corn rows, I think. Another time she said my main character’s father would not have a rolltop desk in his home, believing that the father would be illiterate and have no need for a rolltop desk. I maintained that my main character could read and write, sat there to read his newspaper and to write out bills. Another time an art editor wanted to place a horrifying picture of a Black man hanging in the afterward of my fiction book to illustrate the horror. I refused. When I’ve had to deal with this kind of editorial arrogance on an editor’s part, I’ve simply said, “Go on and publish it but take my name off the book.” That has caused senior editors to step in and support me.

That’s tough. One editor and I had battles over every chapter. One of my books takes place in 1904. My main character lives in a lower middle-class, rural Black family. My editor insisted that my main character should wear “plaits.” I maintained that as a member of a striving Black family the mother would never let her daughters wear “plaits.” I’d started out writing that she wore “French braided” hair. Editor said that was not in fashion in 1904, and substituted “plaits.” Well, that did it. We compromised with corn rows, I think. Another time she said my main character’s father would not have a rolltop desk in his home, believing that the father would be illiterate and have no need for a rolltop desk. I maintained that my main character could read and write, sat there to read his newspaper and to write out bills. Another time an art editor wanted to place a horrifying picture of a Black man hanging in the afterward of my fiction book to illustrate the horror. I refused. When I’ve had to deal with this kind of editorial arrogance on an editor’s part, I’ve simply said, “Go on and publish it but take my name off the book.” That has caused senior editors to step in and support me. I think everyone likes to be recognized for their work. Celeste’s Harlem Renaissance received the 2007 North Carolina Book Award-American Association of University Women Award for Juvenile Literature and I am truly honored. Awards for me are few and far between, too. That’s why being one of the Brown Bookshelf’s authors means to much to me. It’s very difficult to break through. My books have a certain amount of notoriety because I deal bluntly and I hope honestly with the African American experience as I perceive it, and I don’t let whites off the hook.

I think everyone likes to be recognized for their work. Celeste’s Harlem Renaissance received the 2007 North Carolina Book Award-American Association of University Women Award for Juvenile Literature and I am truly honored. Awards for me are few and far between, too. That’s why being one of the Brown Bookshelf’s authors means to much to me. It’s very difficult to break through. My books have a certain amount of notoriety because I deal bluntly and I hope honestly with the African American experience as I perceive it, and I don’t let whites off the hook. I write about my Carolina Trilogy in my scholarly piece “Tracing the Trilogy” in African American Review (Spring 1998; Dr. Diane Johnson Feelings, Editor). My wonderful editor Jean Vestal would cross out chunks of The Secret of Gumbo Grove and remind me that ” ‘you can’t put the whole history of Black America into this one book, Eleanora. You’re telling the story of just one little girl.’ Jeanne was right. What I had to tell wouldn’t fit into one book.” (p. 77) After The Secret of Gumbo Grove (Watts, 1987) came Thank You, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.! (Watts, 1990) and A Blessing in Disguise (Delecorte, 1995; reprinted, Just Us Books, 1999). All three are still in print, or they were this morning.

I write about my Carolina Trilogy in my scholarly piece “Tracing the Trilogy” in African American Review (Spring 1998; Dr. Diane Johnson Feelings, Editor). My wonderful editor Jean Vestal would cross out chunks of The Secret of Gumbo Grove and remind me that ” ‘you can’t put the whole history of Black America into this one book, Eleanora. You’re telling the story of just one little girl.’ Jeanne was right. What I had to tell wouldn’t fit into one book.” (p. 77) After The Secret of Gumbo Grove (Watts, 1987) came Thank You, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.! (Watts, 1990) and A Blessing in Disguise (Delecorte, 1995; reprinted, Just Us Books, 1999). All three are still in print, or they were this morning. It wasn’t until I had finished Gumbo Grove that I felt the need to place two more books along the coast of South Carolina in mythical Calvary County. I write about neighborhoods and communities and families not written about before by an African American author, and from the viewpoint of an African American child. I personally believe there’s a difference in the authenticity of books written by someone from within the culture and books written by someone from without. I’ll accept that anyone has a right to write about any ethnicity/culture he/she wants, but not everybody from outside that culture does it well. Not everybody does it well from the inside, either, but over the long run you do it better.

It wasn’t until I had finished Gumbo Grove that I felt the need to place two more books along the coast of South Carolina in mythical Calvary County. I write about neighborhoods and communities and families not written about before by an African American author, and from the viewpoint of an African American child. I personally believe there’s a difference in the authenticity of books written by someone from within the culture and books written by someone from without. I’ll accept that anyone has a right to write about any ethnicity/culture he/she wants, but not everybody from outside that culture does it well. Not everybody does it well from the inside, either, but over the long run you do it better. Thank You, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.! involved pride of who you are, intra-racial color consciousness — always very real in the Black community — and finding a sense of place in one’s home. Those are touching subjects that go to the heart of our families. A Blessing in Disguise was based on what I saw around me in Myrtle Beach, SC, where we lived from 1978 to 1992, when crack cocaine began devastating our neighorborhoods. I think we were living in the middle of it, and it seemed that the police, the politicians and the preachers looked the other away, as long as drug money was being put in the collection plates.

Thank You, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.! involved pride of who you are, intra-racial color consciousness — always very real in the Black community — and finding a sense of place in one’s home. Those are touching subjects that go to the heart of our families. A Blessing in Disguise was based on what I saw around me in Myrtle Beach, SC, where we lived from 1978 to 1992, when crack cocaine began devastating our neighorborhoods. I think we were living in the middle of it, and it seemed that the police, the politicians and the preachers looked the other away, as long as drug money was being put in the collection plates.

My first homework assignment for the 28 Days Later campaign was to read the book

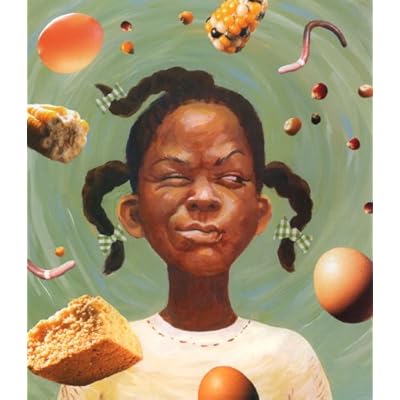

My first homework assignment for the 28 Days Later campaign was to read the book  Janice: The Chicken Chasing Queen of Lamar County is the story of a little girl who wants to catch a favorite chicken that she calls Miss Hen, but Miss Hen has other ideas. Home wisdom, patience, and steadfast determination finally bring our heroine face-to-face with her quarry. Miss Hen, however, is a chicken with a secret, leaving our unredeemed chicken chaser a difficult decision.

Janice: The Chicken Chasing Queen of Lamar County is the story of a little girl who wants to catch a favorite chicken that she calls Miss Hen, but Miss Hen has other ideas. Home wisdom, patience, and steadfast determination finally bring our heroine face-to-face with her quarry. Miss Hen, however, is a chicken with a secret, leaving our unredeemed chicken chaser a difficult decision. Janice: Chicken Chasing is based on my obsession with chasing my grandmother’s chickens. I was a wicked child, and it was my childhood ambition to catch a chicken or at least splash one with water from the hand basin on the back step.

Janice: Chicken Chasing is based on my obsession with chasing my grandmother’s chickens. I was a wicked child, and it was my childhood ambition to catch a chicken or at least splash one with water from the hand basin on the back step.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then a painting by Sean Qualls is surely worth one-hundred-times more.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then a painting by Sean Qualls is surely worth one-hundred-times more.

Don: How did you become interested in illustrating for children?