Consider: a lecture hall of undergraduates, bored and fidgety (and techne-deprived, since I’ve banned computers and devices in class) in distinctive too-cool-for-school Philosophy 101 style.—Ah, but today will be different: the current offering is not Aristotle on causation, or Cartesian dualism, or Kant’s transcendental unity of apperception—no.

The post Our exhausted (first) world: a plea for 21st-century existential philosophy appeared first on OUPblog.

By Joseph Harris

One of the most intriguing developments in recent psychology, I feel, has been the recognition of the role played by irrationality in human thought. Recent works by Richard Wiseman, Dan Ariely, Daniel Kahneman, and others have highlighted the irrationality that can inform and shape our judgements, decision-making, and thought more generally. But, as the title of Ariely’s book Predictably Irrational reminds us, our ‘irrationality’ is not necessarily random for all that; in fact, there often appears to be something systematic and internally coherent about the sorts of mistakes that we make. For example, when we’re judging probabilities, we tend to vastly overestimate the likelihood of more dramatic outcomes (such as dying in an aeroplane crash) and underestimate that of less striking ones (such as dying of heart disease). Similarly, we’re very susceptible to whatever information is made ‘available’ to us. As Kahneman suggests, for example, we tend to typecast public figures like politicians as unduly prone to infidelity – not because of any solid statistical evidence, but because journalists’ exposure of such affairs makes the association spring to mind more readily. But our irrationality does not end there. In a further step, we often then compound our mistake by seeking to derive from it explanatory theories and narratives about, say, the aphrodisiac nature of power, and these explanations then help give credence and plausibility to our misguided assumptions.

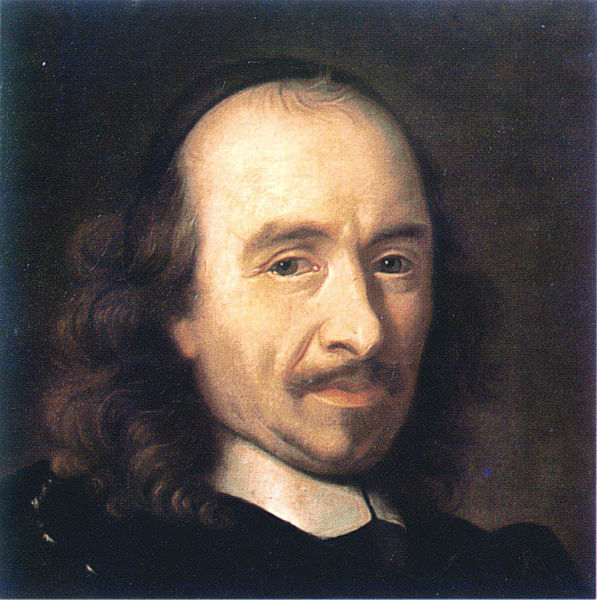

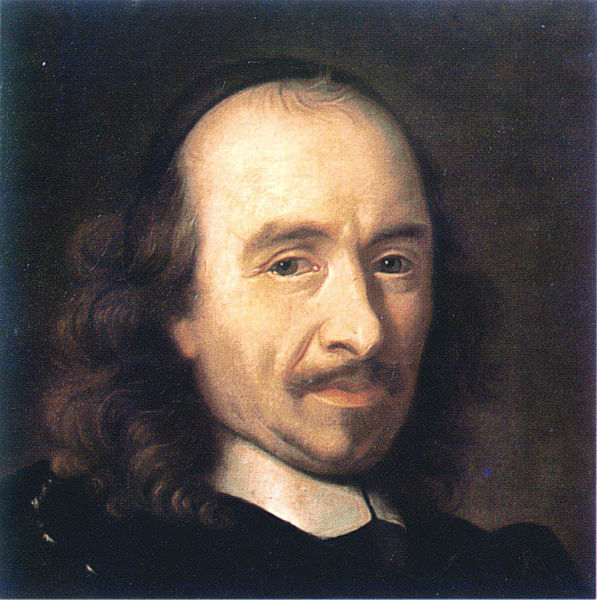

This interest in the ‘cognitive biases’ of the human mind is nothing new. Long before psychology or behavioural economics developed as formalised disciplines, dramatists and dramatic theoreticians were keen to isolate and either exploit or overcome the predictable irrationality of theatre audiences. The so-called ‘father of French tragedy’, Pierre Corneille (1606-84), was particularly fascinated by the vagaries of audience response and eager to exploit his findings in his plays. Some of Corneille’s most interesting observations lie in the very area which has recently attracted Kahneman and others: our capacity to assess probability. This was a key issue for many seventeenth-century dramatists, not least because of the period’s insistence on aesthetic vraisemblance (‘verisimilitude’ — essentially, the dramatic fiction’s overall plausibility), as the backbone of dramatic illusion.

Corneille takes a similar observation to Kahneman and turns it into a sort of aesthetic principle. As Corneille notes, tragedians (like modern journalists) typically focus on the crimes and misdemeanours of the notable and powerful. Corneille’s explanation for this is simple: only famous people’s misfortunes and deaths are typically ‘illustrious’ or ‘extraordinary’ enough to have been recorded by history, and thus to have the external historical backing that otherwise implausible events require. Spectators, he claims, are quick to mistrust tragic narratives they do not already know – not so much because the tragic events are themselves implausible (although they may well be), but because it is implausible that such implausible events occurred without having already been brought to their knowledge. (In contrast, comic plots can be entirely invented because they focus on private, domestic events that escape the public radar.) So although Corneille’s spectators display a very patchy grasp of history, they cling tenaciously to what they do know — thus embodying what Kahneman calls ‘our excessive confidence in what we believe we know, and our apparent inability to acknowledge the full extent of our ignorance and the uncertainty of the world we live in’.

Does this mean that Corneille’s spectators deduce — as Kahneman suggests we do of politicians’ affairs — that such murderous deeds are more prevalent amongst kings and queens? Corneille certainly claims that ancient Greek tragedy played an important role in republican propaganda, fostering its audiences’ belief that kings were fated to lives of brutality. But Corneille uses a rather different logic when explaining the responses of his own contemporaries, those dutiful subjects of Louis XIV. Corneille, we remember, insists that our prior familiarity with historical narratives can win ‘belief’ for otherwise improbable tragic plots; the details of history have already won our belief, however implausible we recognise them to be. In other words, we tend to regard each tragic hero’s downfall as a discrete, one-off historical phenomenon – one chosen for the stage, indeed, precisely because of its uniqueness – rather than as something reflecting a more general propensity towards untimely or brutal ends amongst the upper classes.

Yet Corneille also implies that, despite recognising this uniqueness, we also crave to see a wider resonance and relevance in each tragic narrative. While watching a tragic hero’s downfall, he claims, we deduce that if even kings can be brought down by passions then lowly commoners like ourselves are at even greater risk of a misfortune proportionate to our station.

It seems, then, that however weak our own passions, and however little we stand to lose by being brought down by them, we commoners are actually far more susceptible to misfortune than the regal figures that appear so appealing to tragic dramatists. Strangely, then, Corneille takes a similar starting point to Kahneman, and shows a similar concern for cognitive biases, but ends up at a conclusion completely contrary to Kahneman’s – reminding us, in case we needed reminding, that there may be various different ways of being coherently irrational.

Joseph Harris is Senior Lecturer in French at Royal Holloway, University of London. He has published widely on seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French literature (especially drama), and is the author of Hidden Agendas: Cross-Dressing in Seventeenth-Century France (Narr, 2005) and Inventing the Spectator: Subjectivity and the Theatrical Experience in Early Modern France (OUP, 2014). He is interested in how early modern French theatre engages with such issues as gender, psychology, laughter, and spectatorship, and he is currently writing a monograph on death in the works of Pierre Corneille. He can be followed on Twitter at @duckmaus.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Pierre Corneille, Anonymous artist, 17th century. Palace of Versailles. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Plausible fictions and irrational coherence appeared first on OUPblog.

We talk a lot about how subjective this business is, about how an agent could be rejecting your book simply because she doesn’t like dogs and you have a dog as a sidekick, or because she doesn’t like characters named Sara. And this is true, but not to the extreme I think some of you like to think or agents like to use as examples. Certainly there are times when we reject books or queries simply because it’s not the type of thing we represent or are interested in representing. For example, I won’t even bother to read Tom Clancy-esque military thrillers because I have no interest in them. They are not my forte, so in that case it is entirely personal preference.

When reading in a genre I do represent, however, there’s more that goes into a request for more or a rejection, more than just the fact that I love dogs or am entranced with Steampunk. My subjectivity is often also based on the market or how well the concept is working for me (which of course is subjective). For example, I love all things food. Query me with a chef or restaurateur and you’ve immediately piqued my interest. That doesn’t mean that just because you’ve included a chef or restaurateur in your book I’m going to offer representation. There’s so much more to it than that, so much more to it than just my personal preference.

When judging a manuscript, whether I’m reading it for myself or for someone else, my subjectivity comes into play in how the book works for me, not that I don’t like dogs. In other words, I might not like dogs, but does the dog in your manuscript work? Does it have a role, does it feel like it belongs, is the purpose of the dog realistic? That’s the trick. A good author will make the book work for just about anyone. If it’s not working, that’s the problem, and that’s when I’ll remember that I don’t like dogs.

Jessica

I did a blog post a while back in which I made the mistake of using what I thought at the time was an innocuous example of rejecting a work because the characters were unlikeable. These two words, "unlikeable characters," set off a bit of a sh**storm, if you’ll excuse my language.

What many of you tend to forget is that this business is subjective, and the likeability of characters, the likeability of people, is subjective. In the comments section you listed a number of examples of characters you felt were unlikeable but clearly worked in literature, one of whom was Lisbeth Salander from the Stieg Larsson series. I didn’t find her unlikeable at all. I thought she was damaged, odd, interesting, and intriguing. Not unlikeable. My opinion, of course.

For me likeability tends to coincide with one-dimensional. A character being unlikeable usually means she has no redeeming qualities, and usually even unlikeable people have a redeeming quality or two, something that gives them more depth. Lisbeth Salander, for example, has a vulnerability that gives her an intriguing dimension. And I find that true of any successful but unlikeable characters, typically they have qualities that make them likeable, or at least intriguing. Maybe they have a brilliant mind or damaged past. Either way, we desperately want to know more about them, want to spend more time with them, despite the fact that they repel us.

The other thing to consider when writing an unlikeable character is what genre you’re writing. In romance, for example, it’s really hard to write an unlikeable hero. Sure he can be damaged and yes, he can definitely have flaws, but your readers, along with your heroine, need to fall in love with him, so we need to see the good side of him too. And that’s just one example.

Certainly if an agent or editor tells you she didn’t find your character likeable, you can ignore what she says, assuming it’s subjective, and find someone who does. Or you could take a close look at your character to see if possibly it’s that she needs that thing (or two) to give her more depth and vulnerability.

Jessica

Great insight to keep in mind.

Well said.

I'm reminded of a book I once read about Christmas tree farming in Wisconsin. I am not interested in Christmas, trees, or Wisconsin, but I couldn't put it down.

How very true, Jessica! I'd hazard to guess that most agents look for voice first, and if the voice fails them, they often then notice the dogs that they so terribly despise.

@tericarter - Good point. I often value books for when they teach me to appreciate the unexpected or unknown, broadening my horizons in some fascinating and inimitable manner.

I may be wrong, but I think you just validated how subjective it all is with this post. In other words, if a dog in a book doesn't work for you than you're obviously not going to be interested. Or, if chef in a book doesn't work for you...even though you love food books...you're not going to be interested. The same dog (or chef), however may work for another agent, which is the same with readers. It's also why we see so many one star and five star reviews for Jonathan Franzen's new book, FREEDOM. (In FREEDOM I don't think the Joey charater's business venture with the government worked, but many people did think it worked...subjectivity again.)

You almost had me on your corner with this one :) But, speaking from a subjective pov, even though the post works well, it doesn't make any sense at all with respect to the title of the post.

I use subjectivity to remind myself that I'll always have a chance at getting published. You never know when you might tap an agent at the right time or you've written something they'll totally fall in love with.

I also use it to try and figure out which agents might be the best fit. For example, I read a book that BookEnds helped put out there. While I, ah, was glad it was an ARC and that I hadn't bought it myself, it still helped me to get a taste of what works for you and what has publishing potential.

LOL, I'll try to keep that in mind as you have my ms with both a dog and a character named Sarah! :))

I get it. But how can you make that come across in a query? For example, an agent reads my query, and rejects it based on some subjective quality. How do you get it past query so the agent can see it's worth its salt?

Ah yeah. I think you're right, calling getting an agent "totally subjective" isn't necessarily true. When an author blames their query getting rejected on the subjectivity of all agents, it reminds me of a girl getting dumped and saying, "He said it wasn't me. It was him."

and I just kind of go, "Isn't that what your last bf said?"

"Yeah?"

"and...those 29 bfs before that?"

"Yeah, guys are just so fickle."

"...fickle yeah. It must be them."

Cause the truth is, while there may be hundreds of nuances and factors going into it, agents are still looking for talent and skill, and yes, when you query properly, to agents who represent your genre, I really do believe they react to talent and skill quite logically, and oftentimes, similarly.

"Doesn't work for me" is shorthand for a whole lot of things that are most likely not subjective at all.

And submitting a Tom-Clancy-like novel to an agent who doesn't represent that genre doesn't get you rejected because of "subjectivity." You were rejected because you didn't do your research.

Bam.

I have never been wild about Neil Gaiman's writing.

NOW, WAIT JUST A MINUTE WITH THOSE PITCHFORKS!

That doesn't mean I don't like his books, or that I can't see how well-written they are. It just means, for whatever reasons, the books don't resonate with me they way they do with his fans.

If I were an agent, and Neil Gaiman queried me, I'd be interested, but I truly wouldn't comprehend what a gold mine I was looking at.

And that means Neil Gaiman would do better to find another agent who did.

Subjectivity is the difference not only between getting an agent and not getting an agent, but between having a competent agent and having a zealous, battle-through-fire champion on your side.

I think your last sentence sums it up perfectly. It's about presentation. You can have the best idea in the world and mess it up with bad execution.

I think what is most difficult for the querying author is determining when it is truly a matter of subjectivity, or a matter of needing improvement. Phrases such as, "I encourage you to query widely." or such even in a personalized rejection can send an author into throes of rejectomancy. One is almost unsure of the need to submit elsewhere or fiddle based on the scraps of feedback. It can be a maddening process.

Thankfully, there are more regular readers than there are agents and editors...one day we'll be able to find an audience that, although as fickle, has more fish in the sea!