By Kenneth M. Ludmerer

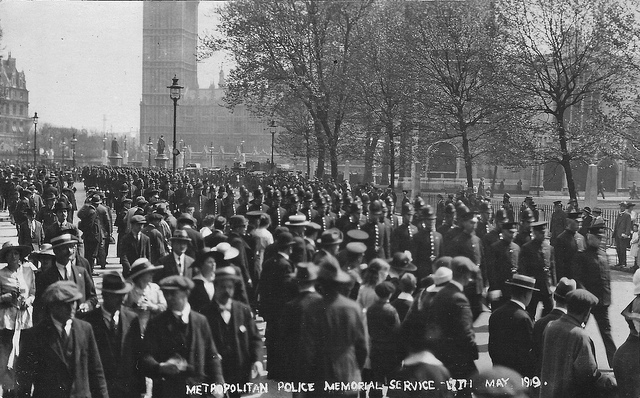

Since the late nineteenth century, medical educators have believed that there is one best way to produce outstanding physicians: put interns, residents, and specialty fellows to work in learning their fields. After appropriate scientific preparation during medical school, house officers (the generic term for interns, residents, and specialty fellows) need to jump into the clinical setting and begin caring for patients themselves. This means delegating to house officers the authority to write orders, make important management decisions, and perform major procedures. It is axiomatic in medicine that an individual is not a mature physician until he has learned to care for patients independently. Thus, the assumption of responsibility is the defining principle of graduate medical education.

To develop independence, house officers receive major responsibilities for the care of their patients. They typically are the first to evaluate the patient on admission, speak with the patients on rounds, make all the decisions, write the orders and progress notes, perform the procedures, and are the first to be called should a problem arise with one of their patients. Such responsibility allows house officers not only to develop independence but also to acquire ownership of their patients — the sense that the patients are theirs, that they are the ones responsible for their patients’ medical outcomes and well-being. Medical educators view the assumption of responsibility as the factor that transforms physicians-in-training into capable practitioners.

Independence and responsibility are not given to house officers cavalierly. Rather, they are earned by residents who show themselves to be mature and capable. Responsibility is typically provided in “graded” fashion — that is, junior house officers have much more circumscribed responsibilities, while more experienced house officers who have accomplished their earlier tasks well are advanced to positions of greater responsibility. The more a resident has progressed, the more independence that resident receives.

The assumption of independence and responsibility comes at different rates for different house officers. Advancement to positions of greater responsibility occurs relatively quickly in cognitive fields like neurology, pediatrics, and internal medicine. There, assistant residents in their second or third year receive decision-making authority even for very sick individuals. Among these fields, house officers in pediatrics are generally monitored more closely because of the fragility of their patients, particularly babies and toddlers. Advancement occurs more slowly in procedural fields, such as general surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, and the surgical subspecialties. In these fields, technical proficiency is so important that residents have to wait many years, sometimes until they are chief residents, to perform certain major operations. The degree of independence afforded house officers also depends on the traditions and culture of individual hospitals. At community hospitals, where private physicians are in charge of their own private patients, house officers often receive too little responsibility. At municipal and county hospitals, where charity patients predominate and teaching staffs are often small, house officers can easily receive too much.

The assumption of responsibility does not mean there is no supervision of house officers. Quite the contrary. House officers are accountable to the chief of service, they have regular contact with attending physicians, and chief residents keep an extremely close eye on the resident service. Moreover, someone more senior is typically present or, if not physically present, immediately available. Thus, interns are closely watched by junior residents, junior residents by senior residents, and senior residents by the chief resident. One generation teaches and supervises the next, even though these generations are separated only by a year or two. Backup and support are available for all residents from attending physicians, consultants, and the chiefs of service. The gravest moral offense a house officer can commit is not to call for help.

From the perspective of patient safety, it may seem that patients should be seen only by experienced physicians and surgeons. However, medical educators have recognized all along that this is not a viable option. Medical education incurs the dual responsibility for ensuring the current safety of patients seen during the training process and the future safety of patients of tomorrow seen by those undergoing training today. Every physician needs to gain clinical experience, and every physician faces a day of reckoning when he practices medicine independently for the first time—that is, without anyone looking over his shoulder or immediately available for help. The only choice medical educators have is to control the circumstances in which this will happen. Should house officers gain experience and develop independence within the structured confines of a teaching hospital, where help can readily be obtained, or must this occur afterward in practice at the potential expense of the first patients who present themselves?

Thus, maximizing safety in graduate medical education is a complex task, for the needs of both present and future patients must be taken into account. The system of graded responsibility provided house officers by the residency system, coupled with careful supervision of house officers’ work, has been developed to maximize professional growth among trainees while at the same time maximizing the safety of patients entrusted to them for care. The system is not perfect, but no one in the United States or anywhere else has yet come up with a better system, and it continues to serve the public well.

Kenneth M. Ludmerer is Professor of Medicine and the Mabel Dorn Reeder Distinguished Professor of the History of Medicine at the Washington University School of Medicine. He is the author of the forthcoming Let Me Heal: The Opportunity to Preserve Excellence in American Medicine (1 October 2014), Time to Heal: American Medical Education from the Turn of the Century to the Era of Managed Care (1999), and Learning to Heal: The Development of American Medical Education (Basic Books, 1985).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Independence, supervision, and patient safety in residency training appeared first on OUPblog.

By Megan O’Neill

It will not come as news to say that the public police are working under challenging conditions. Since the coalition government came to power in 2010, there have been wide-ranging and deep cuts to the funding of public services, the police included. This was the institution which once enjoyed a privileged position as the “go-to” service for political parties to improve themselves in the eyes of the electorate by being “tough on crime” through ever increasing police numbers. Numbers of police officers and staff rose year on year from 2000 to 2010, an increase of 13.7%. All that has now changed, and the most recent statistics show that the police service has now reduced in size by 11%, and is roughly equivalent to where it was in 2001. While police officers themselves cannot be made redundant, vacant positions are not being filled when officers leave or retire. Police and Community Support Officers (PCSOs) can be made redundant, and this has happened in a few areas, as well as vacancies not being filled. What does this mean for being “tough on crime”?

Well, to be honest, not much on face value. As any good first year Criminology student should be able to tell you, the overall crime rate has been falling more or less steadily since 1995. This drop in crime started before police numbers rose, and occurred in other countries as well where police numbers may not have changed to the degree they did in England and Wales. The cause for the drop in crime is the subject of much debate, and will not be pursued in depth here. However, what is clear is that the sheer number of police officers in a police force does not have a direct link with the amount of crime that area experiences. What is more important is what is done with those officers, and this is where my concern with the current state of policing lies.

While the last Labour government regularly pumped up the number of officers to redress their image of being soft on crime, they also made two significant changes to policing practice. One was the introduction of PCSOs in 2002 and the other was the national roll-out of Neighbourhood Policing in 2008. While both may have been derided in the beginning as being more for show than of any real substance, I feel both have made significant changes in the relationship of the police to many local areas and with this has come a reorientation to the police occupational culture itself. Research I have conducted on partnership work and PCSOs suggests that these changes have made some sections of the police more open to working with those outside of their organisation, has enhanced the commitment the police have to crime prevention and long-term problem solving, and has led to better information sharing and relationships between the police and local residents.

To be clear – I am not arguing that all is fine and well in policing. However, the situation we have now is far better than what was the case in the 1980s and 1990s. Rather than “community policing” referring to police officers in panda cars whizzing through residential areas, going from job to job, we now have officers and staff who walk their beats, get to know many of the people and places within it and have the time to attend to the “small stuff”. By this I mean the anti-social, low-level crimes and incivilities which may not set performance targets on fire, but which mean a great deal to the daily lives of thousands of people. Officers, usually PCSOs, can take the time to find out about these concerns and either address the matter themselves or find the most appropriate partner agency to do so (the staff of which they know by name and often have their numbers programmed into their mobile phones). In return, residents start to build trust in their local neighbourhood team, which may develop over time into information sharing of interest to constables and detectives.

However, all this is now in danger of being eroded. The budget cuts mean that the officers and staff who remain in neighbourhood teams have much heavier workloads, including the PCSOs. It is far more difficult now to attend to the “small stuff” and to conduct visible patrols. Partner agencies are also facing severe budget cuts and this will impact on their ability to work collaboratively with the police as they have fewer resources to share. This means that the police lose opportunities to make connections in their local communities and build valuable social capital. Residents are not getting the attention they desire from their local police and so will have fewer reasons to trust them. In addition to these losses to police practice and community relationships is a much less visible but no less significant loss – the reorientation of the police occupational culture. Police officers became more open to working with partners, PCSOs, residents and to consider long-term problem solving once they had experienced the benefits of doing so. Many of the traditional hostilities towards the “other” were reducing noticeably among the neighbourhood officers with whom I have conducted research. This widening of the police world view will, I fear, also be lost in the current budget structures. This is not a savings for policing – it is a very high cost indeed.

Dr Megan O’Neill is the Chair of the British Society of Criminology Policing Network, and a lecturer at the Scottish Institute of Policing Research, University of Dundee. She is the author of “Ripe for the Chop or the Public Face of Policing? PCSOs and Neighbourhood Policing in Austerity” (available to read for free for a limited time) in Policing.

The full article will be available this June in Policing, A Journal of Policy and Practice, volume 8.3. This peer-reviewed journal contains critical analysis and commentary on a wide range of topics including current law enforcement policies, police reform, political and legal developments, training and education, patrol and investigative operations, accountability, comparative police practices, and human and civil rights

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: UK police vehicles at the scene of a public disturbance. © jeffdalt via iStockphoto.

The post The unseen cost of policing in austerity appeared first on OUPblog.

The 90th annual conference of the Police Federation of England and Wales (commonly known as POLFED) starts today in Bournemouth. Running from 20-22 May, the event will see police officers from England, Wales, and further afield join with representatives from policing agencies, the legal profession, and the government to discuss pressing issues from the world of policing and within the Police Federation itself.

To mark the occasion, we’ve put together a list of 10 things you may not know about the Police Federation.

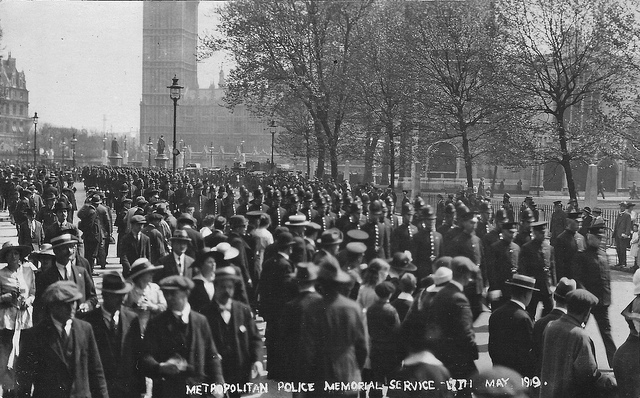

- The Police Federation was founded as result of the Police Act 1919. Ninety years earlier, the Police Act 1829 allowed for the official foundation of the Metropolitan Police, followed by the formation of regional forces across England, Wales, and the rest of the UK.

- The Federation was the first association officially created to protect the rights of police officers, providing a viable Government-supported alternative to the perceived threat of the growing trade union movement. Government officials were worried by continuing unrest in the late 19th and early 20th centuries relating to officers’ pay.

Fallen London Police, 17 May 1919 in Parliament Square. CC BY-SA Leonard Bentley via Flickr.

- The Police Act 1919 also named the Home Secretary as responsible to Government for the police force, an appointment which continues today. As is tradition, current Home Secretary Theresa May will deliver a keynote speech to the annual Police Federation conference, an event which has previously proven controversial with the attendees.

- Representing all officers up to the rank of Chief Inspector, the Police Federation currently has around 127,000 members, from across the 43 forces of England and Wales. Officers above the rank of Chief Inspector are represented by either the Police Superintendents Association of England and Wales, or the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO).

- Outside of England and Wales, there are equivalent organisations across the UK including the Scottish Police Federation and the Police Federation for Northern Ireland, as well as specialist branches for the British Transport Police and the Defence Police Federation for Ministry of Defence Police staff.

- Before the Sexual Discrimination Act 1975, the police service ran separate establishments for men and women, allowing individual forces to control the number of women joining the police. Chief inspectors were responsible for designating appropriate roles for female officers.

- After an apparent rise in assaults on police officers in the late 1980s and early 1990s, including the deaths of two officers, the Police Federation successfully supported a movement for revised safety equipment. As well as uniform changes, the campaign introduced longer, Americanised truncheons, new ‘Quik-kuffs’, and stab-proof vests.

- Although officially politically neutral, the Police Federation took a firm stance prior to the 1979 General Election, placing open letters to candidates in national newspapers. These letters were a sharp critique on the way the previous Labour government had handled police pay, legislation, and crime – things that Margaret Thatcher’s, ultimately successful, Conservative manifesto promised to improve.

- On 20 January 2014, the RSA published the Final Report of the Police Federation Independent Review. Led by Sir David Normington, the review panel assessed how the Police Federation could continue to “act as a credible voice for rank and file police officers.” The 36 recommendations outlined in the report will be discussed at the annual conference.

- This year’s conference will be the last public event of the current Chairman Steve Williams and General Secretary Ian Rennie, who have both chosen to leave their posts, and their roles within the police service, at the end of May.

Blackstone’s will be tweeting from the Police Federation conference. Follow @bstonespolice for our updates and join the conversation using #pfewconf14.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Uk police vehicles at the scene of a public disturbance. © jeffdalt via iStockphoto.

The post 10 things you may not know about the Police Federation appeared first on OUPblog.

![By National Cancer Institute [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Doctor_consults_with_patient_4.jpg)