While out driving one afternoon, I notice a bus speeding down the road towards me. As it approaches, the bus drifts into my lane, forcing me to swerve and strike a parked car. The bus doesn’t stop and, while I glimpse some corporate logo on the side, I’m shaken and I don’t manage to make it out.

The post When probability is not enough appeared first on OUPblog.

By Huw Llewelyn

In medicine, we use two different thought processes: (1) non-transparent thought, e.g. slick, subjective decisions and (2) transparent reasoning, e.g. verbal explanations to patients, discussions during meetings, ward rounds, and letter-writing. In practice, we use one approach as a check for the other. Animals communicate solely through non-transparent thought, but the human gift of language allows us also to convey our thoughts to others transparently. However, in order to communicate properly we must have an appropriate vocabulary linked to shared concepts.

‘Reasoning by probable elimination’ plays an important role in transparent medical reasoning. The diagnostic process uses ‘probable elimination’ rival possibilities and points to a conclusion through that process of elimination. Suppose one item of information (e.g. a symptom) is chosen as a ‘lead’ that is associated with a short list of diagnoses that covers most people with that lead (ideally 100%). The next step is to choose a diagnosis from that list and to look for a finding that occurs commonly in those with that chosen diagnosis and rarely (ideally never) in at least one other diagnosis in the list. If such a finding is found for each of the other diagnoses in the list, then the probability of the chosen diagnosis is high. If findings are found that never occur in each other possibility in the list, then the diagnosis is certain. However, if none of this happens, then another diagnosis is chosen from the list and the process is repeated.

Probabilistic reasoning by elimination explains how diagnostic tests can be assessed in a logical way using these concepts to avoid misdiagnosis and mistreatment. If clear, written explanations became routine, it would go a long way to eliminating failures of care that have dominated the media of late.

Reasoning by probable elimination is important in estimating the probability of similar outcomes by repeating a published study (i.e. the probability of replication). In order for the probability of replication to be high, the probability of non-replication due to all other reasons has to be low. For example, the estimated probability of non-replication due to poor reporting of results or methods (due to error, ignorance or dishonesty) has to be low. Also, the probability of non-replication due to poor or idiosyncratic methodology, or different circumstances or subjects in the reader’s setting, etc. should be low. Finally, the probability of non-replication by chance due to the number of readings made must be low. If, after all this, the estimated probabilities are low for all possible reasons of non-replication, then the probability of replication should be high. This assumes of course that all the reasons for non-replication have been considered and shown to be improbable!

If the probability of replicating a study result is high, the reader will consider the possible explanations or hypotheses for that study finding. Ideally the list of possibilities should be complete. However, in a novel scientific situation there may well be some explanations that no one has considered yet. This contrasts with a diagnostic situation where past experience tells us that 99% of patients presenting with some symptom have one of short list of diagnoses. Therefore, the probability of the favoured scientific hypothesis cannot be assumed to be high or ‘confirmed’ because it cannot be guaranteed that all other important explanations have been eliminated or shown to be improbable. This partly explains why Karl Popper asserted that hypotheses can never be confirmed – that it is only possible to ‘falsify’ alternative hypotheses. The theorem of probable elimination identifies the assumptions, limitations and pitfalls of reasoning by probable elimination.

Reasoning by probable elimination is central to medicine, science, statistics and other disciplines. This important method should have a central place in education.

Huw Llewelyn is a general physician with a special interest in endocrinology and acute medicine, who has had a career-long interest in the mathematical representation of the thought processes used by doctors in their day to day work during clinical practice, teaching and research. He has also been an honorary fellow in mathematics in Aberystwyth University for many years and has had wide experience in different medical settings: general practice, teaching hospital departments with international reputations of excellence and district general hospitals in urban and rural areas. His insight is reflected in the content of the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Diagnosis and the mathematical models in the form of new theorems on which that content is based.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image via iStockphoto.

The post Reasoning in medicine and science appeared first on OUPblog.

In this post, we’ll discuss how to use Maxima to do simple univariate statistics and probability.

A word of warning: before blindly using a new software tool, make sure you weigh its limitations carefully. As a computer geek too eager to try out new tech, I’ve often gotten myself into trouble by ignoring this rule. I can’t count the number of times I’ve invested hours learning a new software only to later find it can’t do what I want it to do (or it can’t do it easily). To help you avoid that trap, here is what Maxima can’t do: stem-and-leaf diagrams, box-and-whisker plots, and grouped data. (Note that, while these features are not built-in to Maxima, an enterprising programmer can easily add them, as I did with quartiles and normal distributions.) Also, Maxima can do histograms, but I haven’t had time to figure out how to use that feature.

Entering Data

First things first, you’ll need a way to get your data into Maxima.

- For small data sets, use an array:

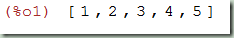

a:[1,2,3,4,5];

This will store the data set {1, 2, 3, 4, 5} into the variable a.

- For large data sets, load the data from a file:

load(numericalio)$ a:read_list(file_search("name"))$

This will store the data set into the variable a.

Measures of Central Tendency and Dispersion

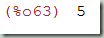

For this section, we’ll assume that the variable a contains the data {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}.

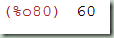

a:[1,2,3,4,5];

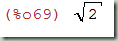

![untitled_4[4] untitled_4[4]](https://lh6.ggpht.com/_8TVezGASlWQ/SZ12owUt3YI/AAAAAAAAAGA/1LzfnQAYePU/untitled_44_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

Note: For the built-in Maxima functions to work, first load the descriptive statistics package: load (descriptive)$

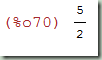

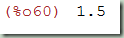

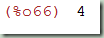

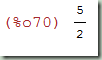

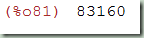

mean(a);

![untitled_5[4] untitled_5[4]](https://lh3.ggpht.com/_8TVezGASlWQ/SZ12pu3T4WI/AAAAAAAAAGY/WxyHTi1whbA/untitled_54_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

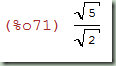

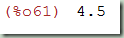

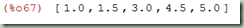

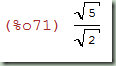

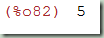

median(a);

![untitled_6[4] untitled_6[4]](https://lh3.ggpht.com/_8TVezGASlWQ/SZ12rDZl1LI/AAAAAAAAAGo/OupgzeF8mhk/untitled_64_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

By default, Maxima uses a different definition for finding the 1st and 3rd quartiles. (No, this doesn’t show how Maxima sucks–it shows that statistics is still more of an “art” than a hard science.) I wrote my own functions to find the usual 1st and 3rd quartiles where the median data point is not included in the calculations. (Download the text file here. Once downloaded, load the file from Maxima’s File>>Open menu.)

quartile1(a);

quartile3(a);

mini(a);

maxi(a);

range(a);

- Find the five statistical summary:

fivenum(a);

- Find the population variance:

var(a);

- Find the population standard deviation:

std(a);

- Find the sample variance:

var1(a);

- Find the sample standard deviation:

std1(a);

Combinatorics

Note: For the built-in Maxima functions to work, first load the functs package: load(functs)$

Permutations

10!;

permutation(5,3);

- Find the permutation of 12 things when there are 2, 4, and 5 distinct repetitions (permutations with repetitions):

12!/(2!*4!*5!);

Combinations

combination(5,4);

The Binomial Distribution

Note: For these functions to work, first load the distrib package

load(distrib)$

and then load my helper functions. (I rewrote the binomial distribution functions to match the TI graphing calculator notation.)

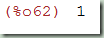

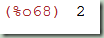

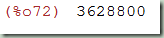

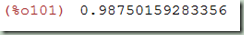

- Find the probability of exactly 40 successes in 100 trials when the probability of success is .3:

binomialpdf(100,.3,40);

![untitled_24[1] untitled_24[1]](https://lh3.ggpht.com/_8TVezGASlWQ/SZ122MdVu1I/AAAAAAAAAIw/Gzw9PDf2ZLo/untitled_241_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

- Find the probability of at most 40 successes:

binom_atmost(100,.3,40);

- Find the probability of at least 40 successes:

binom_atleast(100,.3,40);

The Normal Distribution

Note: The normalcdf function is not part of Maxima. You’ll need to download and load my helper functions.

- If x is a normally distributed random variable with mean 45 and standard deviation 8, find the probability that x is between 40 and 60:

normalcdf(40,60,45,8);

Hello! This is Maddy once again, in case you happened to somehow forget I was guest-blogging. Well, if you thought the highlight of the day was the nice breeze that cooled everything down, or that I got to see some stuff that I saw filmed being edited together, or the fact that I got to go up on the hill today so it wasn’t as dull, you would be wrong. The highlight is that it is my sister, Holly Miranda Gaiman’s birthday today!!!!! She turned 22 which is 10 years older then me, but don’t worry I will be 13 in August and then she will only be 9 years older than me. Joy! She is actually on the plane to Africa. Great way to spend a birthday, I know! Holly is very wonderful and a fabulous sister. She is always optimistic and is always there for me! All in all she is just a great person. Okay enough of the mushy stuff. Whenever Holly comes home she leaves everything a total and complete mess. I swear, I don’t think she could keep a place clean for a day, at the most. Also she is kind of weird sometimes but I guess it runs in the family. Except for me. I’m not weird at all…

Well I looked through my laptop and found all the beautiful pictures of Holly that I could see! Don’t mind the people in the pictures with her. They are of no importance. Don’t mind the strange expressions they are making either.

HAPPY BIRTHDAY HOLLY!