By John Knowles

If you become wealthier tomorrow, say through winning the lottery, would you spend more or less working than you do now? Standard economic models predict you would work less. In fact a substantial segment of American society has indeed become wealthier over the last 40 years — married men. The reason is that wives’ earnings now make a much larger contribution to household income than in the past. However married men do not work less now on average than they did in the 1970s. This is intriguing because it suggests there is something important missing in economic explanations of the rise in labor supply of married women over the same period.

One possibility is that what we are seeing here are the aggregate effects of bargaining between spouses. This is plausible because there was a substantial narrowing of the male-female wage gap over the period. The ratio of women’s to men’s average wages; starting from about 0.57 in the 1964-1974 period, rose rapidly to 0.78 in the early 1990s. Even if we smooth out the fluctuations, the graph shows an average ratio of 0.75 in the 1990s, compared to 0.57 in the early 1970s.

The closing of the male-female wage gap suggests a relative improvement in the economic status of non-married women compared to non-married men. According to bargaining models of the household, we should expect to see a better deal for wives—control over a larger share of household resources – because they don’t need marriage as much as they used to. We should see that the share of household wealth spent on the wife increases relative to that spent on the husband.

Bargaining models of household behavior are rare in macroeconomics. Instead, the standard assumption is that households behave as if they were maximizing a fixed utility function. Known as the “unitary” model of the household, a basic implication is that when a good A becomes more expensive relative to another good B, the ratio of A to B that the household consumes should decline. When women’s wages rose relative to men’s, that increased the cost of wives’ leisure relative to that of husbands. The ratio of husbands’ leisure time to that of wives should therefore have increased.

In the bargaining model there is an additional potential effect on leisure: as the share of wealth the household spends on the wife increases, it should spend more on the wife’s leisure. Therefore the ratio of husband’s to wife’s leisure could increase or decrease, depending on the responsiveness of the bargaining solution to changes in the relative status of the spouses as singles.

To measure the change in relative leisure requires data on unpaid work, such as time spent on grocery shopping and chores around the house. The American Time-Use Survey is an important source for 2003 and later, and there also exist precursor surveys that can be used for some earlier years. The main limitation of these surveys is that they sample individuals, not couples, so one cannot measure the leisure ratio of individual households. Instead measurement consists of the average leisure of wives compared to that of husbands. The paper also shows the results of controlling for age and education. Overall, the message is clear; the relative leisure of married couples was essentially the same in 2003 as in 1975, about 1.05.

One can explain the stability of the leisure ratio through bargaining; the wife gets a higher share of the marriage’s resources when her wage increases, and this offsets the rise in the price of her leisure. This raises a set of essentially quantitative questions: Suppose that marital bargaining really did determine labor supply how big are the mistakes one would make in predicting labor supply by using a model without bargaining? To provide answers, I design a mathematical model of marriage and bargaining to resemble as closely as possible the ‘representative agent’ of canonical macro models. I use the model to measure the impact on labor supply of the closing of the gender wage gap, as well as other shocks, such as improvements to home -production technology.

People in the model use their share of household’s resources to buy themselves leisure and private consumption. They also allocate time to unpaid labor at home to produce a public consumption good that both spouses can enjoy together. We can therefore calibrate the model to exactly match the average time-allocation patterns observed in American time-use data. The calibrated model can then be used to compare the effects of the economic shocks in the bargaining and unitary models.

The results show that the rising of women’s wages can generate simultaneously the observed increase in married women’s paid work and the relative stability of that of the husbands. Bargaining is critical however; the unitary model, if calibrated to match the 1970s generates far too much of an increase in the wife’s paid labor, and far too large a decline in that of the men; in both cases, the prediction error is on the order of 2-3 weekly hours, about 10% of per-capita labor supply. In terms of aggregate labor, the error is much smaller because these sex-specific errors largely offset each other.

The bottom line therefore is that if, as is often the case, the research question does not require us to distinguish between the labor of different household or spouse types, then it may be reasonable to ignore bargaining between spouses. However if we need to understand the allocation of time across men and women, then models with bargaining have a lot to contribute.

John Knowles is a professor of economics at the University of Southampton. He was born in the UK and schooled in Canada, Spain and the Bahamas. After completing his PhD at the University of Rochester (NY, USA) in 1998, he taught at the University of Pennsylvania, and returned to the UK in 2008. His current research focuses on using mathematical models to analyze trends in marriage and unmarried birth rates in the US and Europe. He is the author of the paper ‘Why are Married Men Working So Much? An Aggregate Analysis of Intra-Household Bargaining and Labour Supply’, published in The Review of Economics Studies.

The Review of Economic Studies aims to encourage research in theoretical and applied economics, especially by young economists. It is widely recognised as one of the core top-five economics journals, with a reputation for publishing path-breaking papers, and is essential reading for economists.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

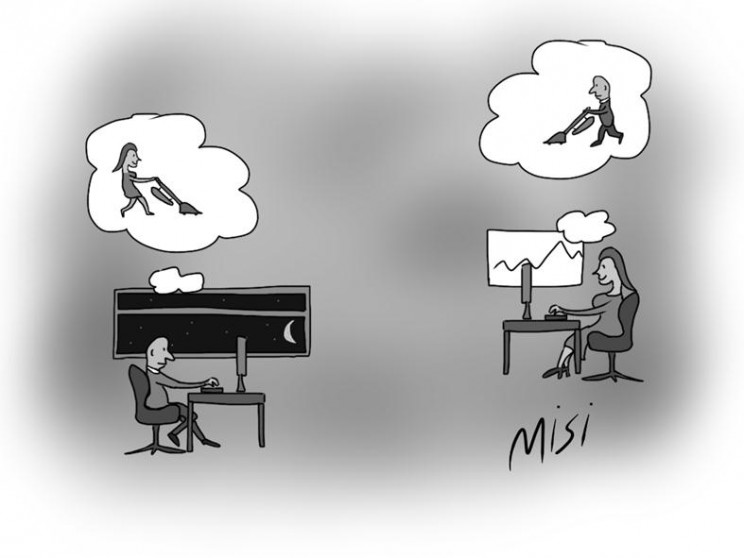

Image credit: Illustration by Mike Irtl. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post Why are married men working so much? appeared first on OUPblog.