By David Rothery

There’s a Patrick Moore-sized hole in the world of astronomy and planetary science that is unlikely ever to be exactly filled. He presented “The Sky at Night,” a monthly BBC TV astronomy programme, from 1957 until his death. This brought him celebrity, and the books that he wrote for the amateur enthusiast were bought or borrowed in vast numbers from public libraries for half a century — including by myself as a schoolboy. Patrick was the mainstay of the BBC’s Apollo Moon-landing coverage that those of us of a certain age will never forget, and there can be few amateur or professional astronomers who grew up in the UK without having been influenced by him. Tributes posted on the Internet show that he was known and admired beyond these shores too. They also attest to Patrick’s extraordinary generosity, exemplified by numerous accounts of how he replied to letters from strangers (of whom in the early 1970s I was one) or took time to chat after his lectures.

Patrick served with distinction and under age as a navigator with Bomber Command during the war. I believe (on the basis of dark hints made during late night conversations) that he also spent time on special operations in occupied Poland, where his youth and assumed Irish identity afforded him a plausible (but surely high-risk) cover story. An encounter with what he referred to as ‘a working concentration camp’ led to his lifelong professed dislike of Germans (“apart from Werner von Braun, the only good German I ever met”).

After the war, Patrick became a school teacher and also very active in the British Astronomical Association notably in its lunar section on account of his painstaking and careful observations of the Moon, some of which were to prove useful for both the American and Soviet lunar missions. He became a friend of the science fiction visionary Arthur C. Clarke, with whom he shared the authorship of Asteroid (2005) sold in aid of Sri Lankan tsunami relief.

I first met Patrick when we were speakers at a meeting to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the discovery of Neptune, so that must have been 1996. He spoke about Neptune itself, and I about its main satellite Triton. Afterwards he was kind enough to remark that he had read my book (Satellites of the Outer Planets). Our first joint TV appearance was “Live from Mars,” an Open University TV programme on a Saturday morning in 1997 when NASA’s Mars Pathfinder landed, allowing us to broadcast the first new pictures from the surface of Mars for nearly 20 years. I became an occasional guest on “The Sky at Night” more recently, which led to a friendship, as with so many of his guests. The programme was usually recorded at Patrick’s home in Selsey, and Patrick delighted to put his guests up overnight, rather than send them to a nearby hotel. That was a cue for an impressively-laden supper table, copious quantities of lubricant, and entertaining — if sometimes outrageous — conversation. Patrick had a wry sense of humour, and would self-parody his supposed extreme views. However, I think he was being serious when, or several occasions, he styled a certain recent US President as “a dangerous lunatic”.

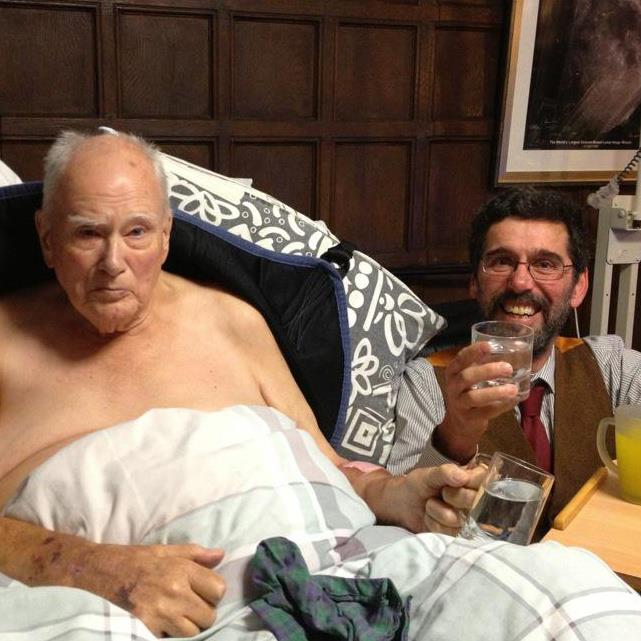

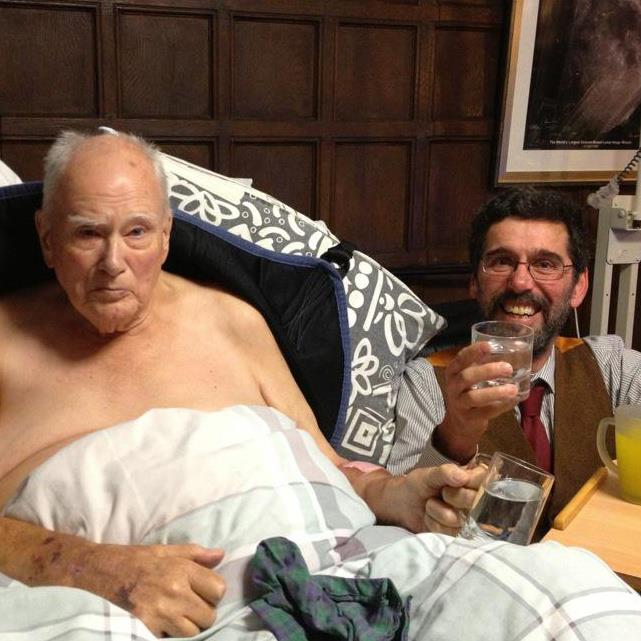

I witnessed Patrick’s mobility decline from walking sticks, to zimmer frame, to wheelchair. His once famously rapid speech became slurry, but his mind and monocle-assisted eyesight stayed sharp. Co-presenters assumed larger and large roles on “The Sky at Night,” but Patrick was always there as the pivotal host. I last saw him less than three weeks before his death, when I guested on what was to prove his last “Sky at Night.” He was drowsy at first, but his intellect soon kicked in. He steered our discussion as ably as of old, and we were treated to a vintage Patrick moment of scepticism “When someone gives me a cupful of lunar water, then I’ll admit I was wrong.”

I lingered afterwards for a chat — inevitably partly about cats. Noticing the time, Patrick ordered a gin and tonic for each of us, and was soon involved in good-natured banter with his carer about why she would not let him have a second. He encouraged me to write a book about Mercury, and kindly agreed to write the foreword if I did. That’s an offer that I shall no longer be able to take him up on, but wherever you are, Patrick, I hope someone’s brought you that cupful of lunar water by now.

Sir Patrick Moore

4 March 1923 – 9 December 2012

Patrick Moore with David Rothery earlier this year.

David Rothery is a Senior Lecturer in Earth Sciences at the Open University UK, where he chairs a course on planetary science and the search for life. He is the author of Planets: A Very Short Introduction.

Image credit: Image is the personal property of David Rothery. Used with permission. Do not reproduce without explicit permission of David Rothery.

The post In memoriam: Patrick Moore appeared first on OUPblog.

By Sydney Beveridge

While Irish eyes are smiling on St. Patrick’s Day, many Finns are already celebrating St. Urho’s Day. The holiday was first celebrated in Minnesota on March 16th, which happens to be just before St. Patrick’s Day.

While Irish eyes are smiling on St. Patrick’s Day, many Finns are already celebrating St. Urho’s Day. The holiday was first celebrated in Minnesota on March 16th, which happens to be just before St. Patrick’s Day.

It honors the legendary Urho, the patron saint of vineyard workers. As the story goes, he saved the grape crop from a grasshopper infestation with his horrible breath as he yelled, “Heinäsirkka, heinäsirkka, mene täältä hiiteen!” (Grasshopper, grasshopper, go away!)

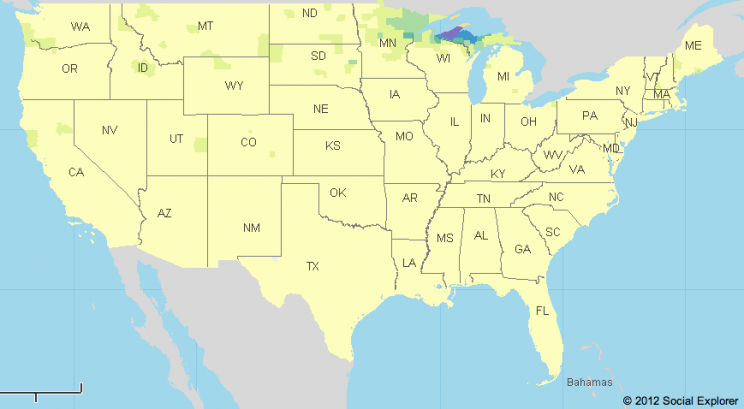

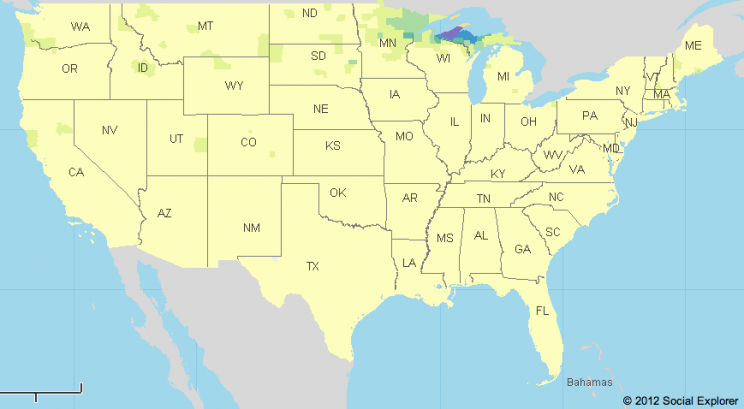

Soon after the first St. Urho’s Day was celebrated, the 1960 census reported that there were 240,827 people in the US born in Finland, representing 0.1 percent of the total population.

Over 15 percent of them resided in Minnesota, where St. Urho celebrations first originated.

According to the 2010 American Community Survey, there are now 647,697 residents of Finnish ancestry, making up about 0.2 percent of the total population.

Some St. Urho’s Day revelers dress up as grasshoppers and grapes to celebrate. As you can see, Finns are especially concentrated in northern Minnesota and Wisconsin. Explore the map to see where you should plan your next St. Urho’s Day outing, or if you are a grasshopper, where to avoid.

Map of Finnish Residents in the US (2006-10 Census)

Happy St. Urho’s Day from Social Explorer!

Sydney Beveridge is the Media and Content Editor for Social Explorer, where she works on the blog, curriculum materials, how-to-videos, social media outreach, presentations and strategic planning. She is a graduate of Swarthmore College and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

By S. J. Connolly

The approach of St Patrick’s day brings to mind once again the ambivalent relationship that historians have with festivals and anniversaries. On the one hand they are our bread and butter. Regular commemorations are what keep the past alive in the public mind. And big anniversaries, like 1989 for historians of the French Revolution, or 2009 for historians of Darwinism, can provide the occasion of conferences, exhibitions, publishers’ contracts, and even invitations to appear on television. On the other hand, historians are trained to look behind supposed traditional observances for the discontinuities and inventions they conceal. They also see it as an important part of their role to point up the gaps between myth, whether popular or official, and what actually happened. All this tends to cast them in the role of spoilsport. When the emphasis is on commemoration, who wants a curmudgeon in the corner pointing out that Britain’s Glorious Revolution was really an evasive compromise that evades the great issues of political principle that were at stake, or that William Wallace was not really Scottish?

Where Ireland is concerned, these issues are all the more familiar, because there anniversaries retain a political significance that elsewhere they have largely lost. In 1991 the Irish government was attacked for its failure to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the rising of 1916. Later in the decade, with republican violence in Northern Ireland suspended and the economy booming, there was a greater willingness to embrace a frankly nationalist version of the Irish past. Events to mark the sesquicentenary of the outbreak of the Great Famine of 1845-51 got stridently under way in 1995, with a renewed emphasis on the crisis, not as a natural disaster, but as a wrong done to the Irish people. Next came the even more enthusiastic celebrations accorded to the rebellion of 1798, presented as a time when Catholic and Protestant supposedly united behind shared national and democratic goals, and hence as a blueprint for post-ceasefire Ireland.

Since then, the urge to commemorate has abated somewhat. The centenary of the act of union (2000) was a muted affair, while the anniversary of Robert Emmett’s insurrection in 1803 was perhaps a victim of the overkill of 1998. Today, however, we can see, looming ahead of us like icebergs out of the fog, a succession of further centenaries to which we will have to find an appropriate response: 1912, when Ulster Protestants, through the mobilization of the Ulster Volunteer Force, took command of their own destiny but also set Ireland on the road to civil war; 1916, the actual centenary (as opposed to the questionable seventy-fifth anniversary) of the Easter Rising; 1920 and 1922, the foundation of two states within a divided Ireland.

Against this uninspiring background St Patrick’s day stands out as a more benign event. Ireland’s patron saint, it is true, has not always been an uncontentious figure. Over several centuries ecclesiastical historians engaged in a frankly partisan debate over whether what Patrick had established was a faithful part of papal Christianity or a proto-Protestant church independent of the authority and doctrinal errors of Rome. Today, in a more secular age, these controversies are largely forgotten. Instead 17 March provides the occasion for a good natured round of parading, celebration and the flourishing of shamrocks and shillelaghs, whose observance extends well beyond Ireland itself. Indeed it is one of the curious features of the event that it is in Washington, rather than Dublin, that senior members of the Irish government are generally to be found on their country’s national day.

Perhaps the most interesting recent developments in the history of St Patrick’s Day have taken place in Belfast. 17 March,

While Irish eyes are smiling on St. Patrick’s Day, many Finns are already celebrating St. Urho’s Day. The holiday was first celebrated in Minnesota on March 16th, which happens to be just before St. Patrick’s Day.

While Irish eyes are smiling on St. Patrick’s Day, many Finns are already celebrating St. Urho’s Day. The holiday was first celebrated in Minnesota on March 16th, which happens to be just before St. Patrick’s Day.