September is Pain Awareness Month. In order to raise awareness of the issues surrounding pain and pain management in the world today, we’ve taken a look back at pain throughout history and compiled a list of the eight most interesting things we learned about pain from The Story of Pain: From Prayer to Painkillers by Joanna Bourke.

- In the past, pain was most often described as an independent entity. In this way, pain was described as something separate from the physical body that might be able to be fought off while keeping the self intact.

- In India and Asia some descriptions of varying degrees of pain involved animals. Some examples include “bear headaches,” that resemble the heavy steps of a bear, “musk deer headaches” like the galloping of a running dear, and “woodpecker headaches” as if pounding into the bark of a tree.

- In the late twentieth century, children’s sensitivity to pain was debated. There were major differences in the beliefs of how children experienced pain. 91 % of pediatricians believing that by the age of two a child experienced pain similarly to adults, compared with 77% of family practitioners, and only 59% of surgeons.

- It had long been observed that, in the heat of battle, even severe wounds may not be felt. In the words of the principal surgeon to the Royal Naval Hospital at Deal, writing in 1816, seamen and soldiers whose limbs he had to amputate because of gunshot wounds “uniformly acknowledged at the time of their being wounded, they were scarcely sensible of the circumstance, till informed of the extent of their misfortune by the inability of moving their limb.”

- Prior to 1846, surgeons conducted their work without the help of effective anesthetics such as ether or chloroform. They were required to be “men of iron … and indomitable nerve” who would not be “disturbed by the cries and contortions of the sufferer.”

- Concerns about medical cruelty reached almost hysterical levels in the latter decades of the nineteenth century, largely as a consequence of public concern about the practice of vivisection (which was, in itself, a response to shifts in the discourse of pain more widely). It seemed self-evident to many critics of the medical profession that scientists trained in vivisection would develop a callous attitude towards other vulnerable life forms.

- In the 19th century it was believed that pain was a necessary process in curing an ailment. In the case of teething infants, lancing their gums or bleeding them with leeches were painful treatments used to reduce inflammation and purge the infant-body of its toxins.

- John Bonica, an anesthetist and chronic pain suffer himself established the first international symposium on pain research and therapy in 1973, which resulted in the founding of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP).

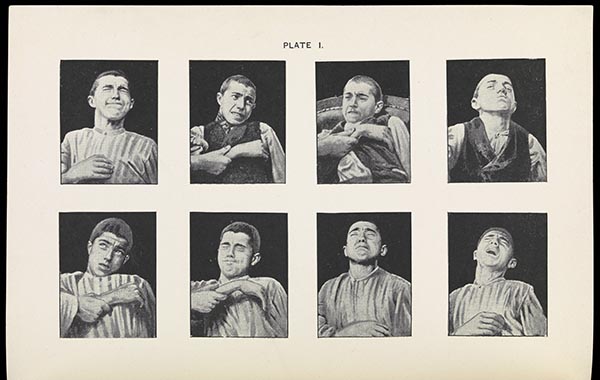

Featured image credit: The Physiognamy of Pain, from Angelo Mosso, Fear (1896), trans. E. Lough and F. Kiesow (New York: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1896), 202, in the Wellcome Collection, L0072188. Used with permission.

The post Eight facts on the history of pain management appeared first on OUPblog.

Pain is a universal experience. Throughout time, everyone knows what it feels like to be in pain — whether it’s a scraped knee, toothache, migraine, or heart attack. Although the feeling of pain may remain the same, the ways in which it was described, treated, and interpreted in the 18th and 19th centuries varies greatly from the ways we regard pain today. The below slideshow of images from The Story of Pain: From Prayer to Painkillers by Joanna Burke will take you on a journey of pain through time.

-

The Cholic

She feels like her waist is being constrained by a rope that is being tightened to an unbearable extent by demons. Other devils prod her with spears and pitchforks. The painting on the wall behind her shows a woman over-indulging in alcohol. Coloured etching by George Cruikshank, after Captain Frederick Maryyat, 1819, in the Wellcome Collection, V0010874. Figure 3.2 Page 64.

-

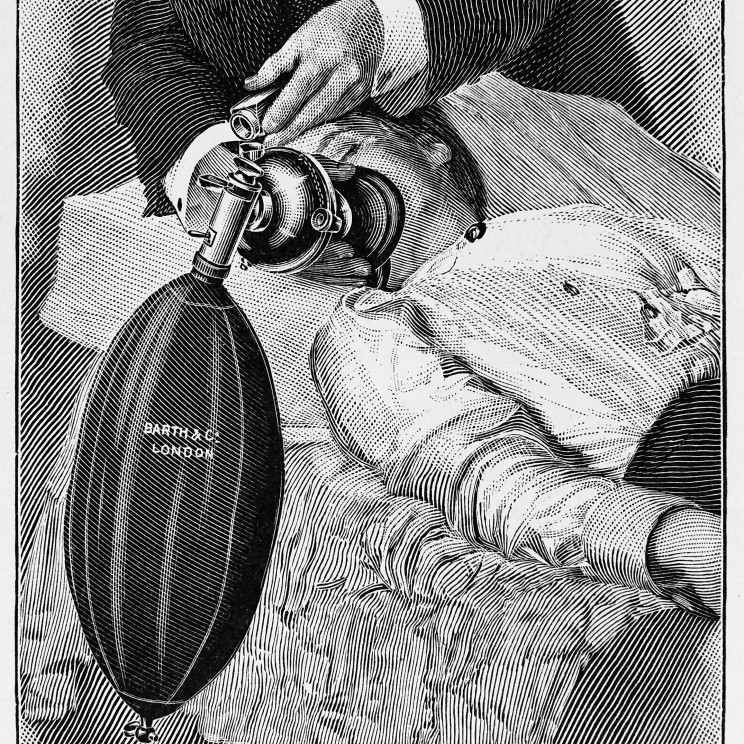

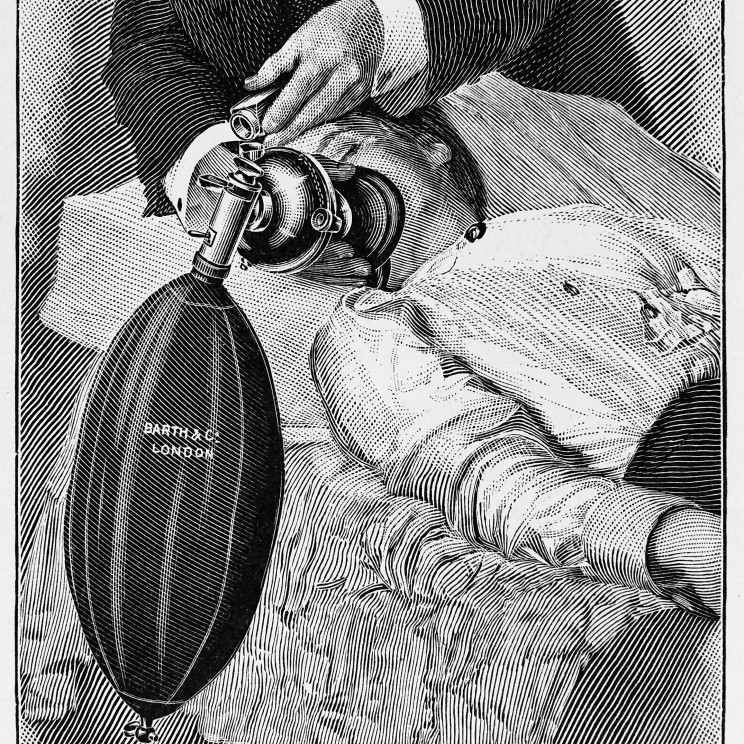

Administration of nitrous oxide

The administration of nitrous oxide and ether by means of the wide-bore modification of Clover’s ether inhaler and nitrous oxide stopcock, from Frederic W. Hewitt, Anaesthetics and their Administration (London: Macmillan & Co., 1912), 583, in the Wellcome Collection, M0009691. Figure 9.3 Page 283.

-

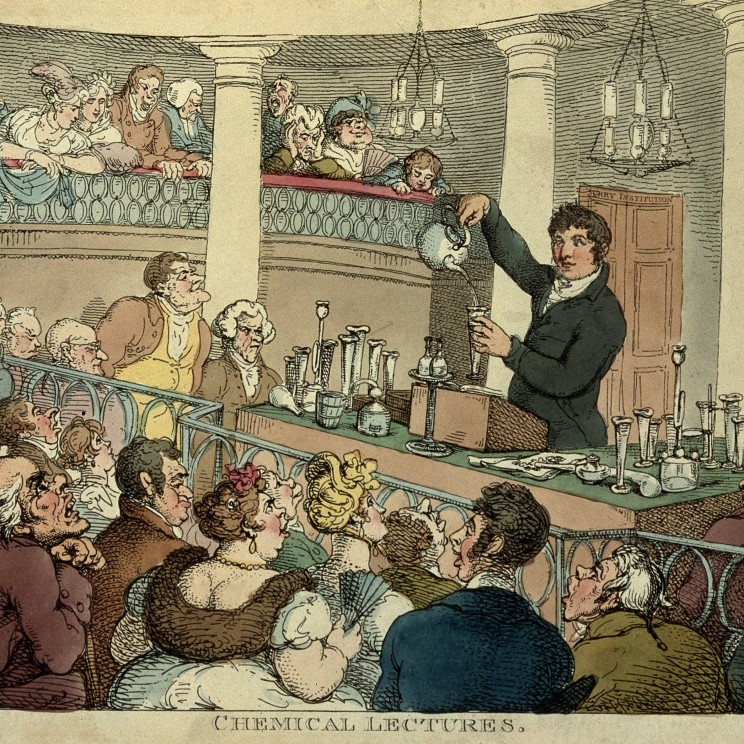

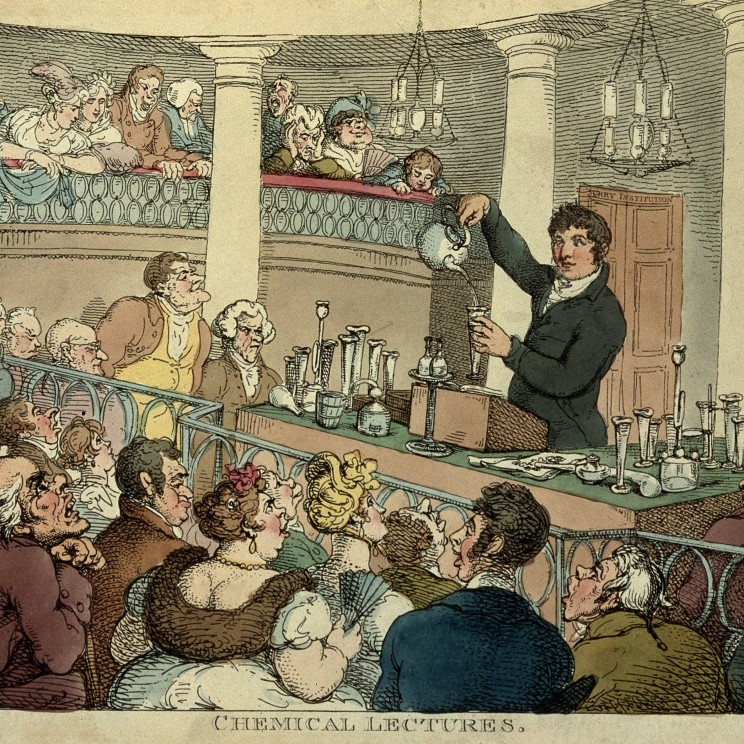

Chemical Lecture

Thomas Rowlandson, “A chemical lecture by Humphrey Davy at the Surrey Institute”, colour etching, 1809, in the Wellcome Collection, L0006722. Figure 9.1 Page 274.

-

Surgeon attending to a wound

Oil painting by Johan Joseph Horemans of an interior with surgeon attending to a wound in a man’s side, 18th cent., in the Wellcome Collection, L0010649. Figure 8.2 Page 234.

-

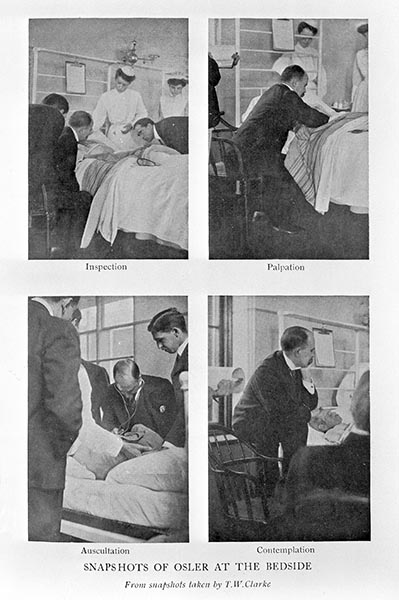

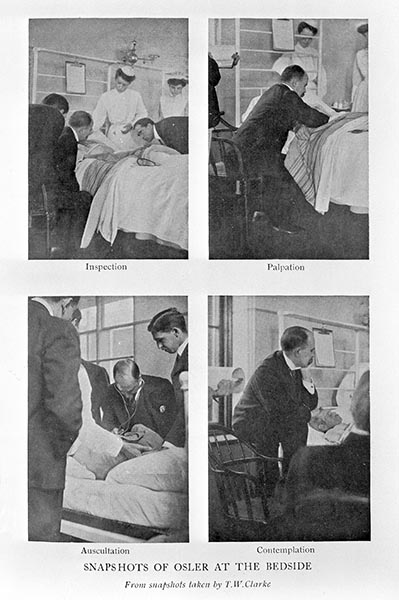

William Osler at bedside of patients

1925, from William Cushing, The Life of Sir William Osler (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1925), 552, in the Wellcome Collection, L0004900. Figure 8.4. Page 259.

-

The process of bleeding

A surgeon bleeding the arm of a young woman, as she is comforted by another woman. Coloured etching by Thomas Rowlandson, c. 1784, in the Wellcome Collection, L0005745. Figure 8.1, Page 233.

-

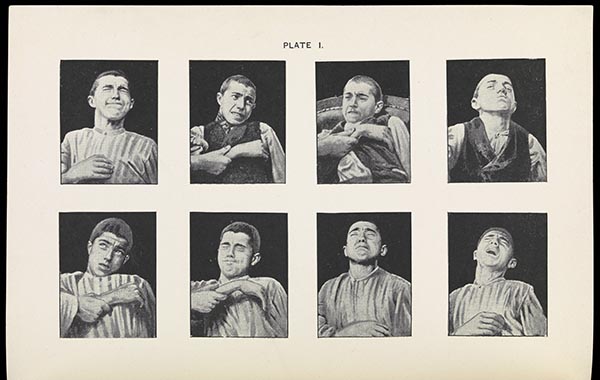

The Physiognomy of Pain

Fear (1896), trans. E. Lough and F. Kiesow (New York: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1896), 202, in the Wellcome Collection, L0072188. Figure 6.3 Page 171.

-

The Morning Prayer

Advertisement card of Dr Jayne’s Tonic, Vermifuge, Carminative Balsam, and Sanative Pills. R. Epp. c 1890s, in the Welcome Collection, L0041194 Figure 4.3. Page 116.

-

Origin of Gout

Gout (caused by excessive alcohol consumption) is portrayed as a burning pain, inflicted by a demon with red-hot pincers. The blackbird is a harbinger of worse to come. Coloured etching after Henry William Bunbury, c. 1780s-1800, in the Wellcome Collection, V0010848. Figure 3.3 Page 66.

Featured image credit: The unconscious man is nothing more than a passive on which little demons equipped with surgical instruments can operate. “The Effect of Chloroform on the Human Body”, watercolour by Richard Tennant Cooper, c. 1912, in the Wellcome Collection, V0017053. Used with permission.

The post The story of pain in pictures appeared first on OUPblog.

By Mark Johnson

The prevalence of chronic pain in the general adult population worldwide may be as high as 30%. Yet pain is not seen as a major health care problem by politicians, probably because people do not die of pain, although many people die in pain. Chronic pain challenges our traditional beliefs about the process of diagnosis, treatment, and cure, with over 40% of individuals reporting inadequate management of chronic pain. Chronic pain is an enigma.

We have all experienced pain and we know with certainty when we have it. Yet, we may doubt others who tell us that they are in pain especially if their pain has a vague or uncertain diagnosis and is not responding to conventional treatment. The medical management of pain evolved from the view that pain is a symptom of pathology and diagnosis, and treatment of pathology will relieve pain. This approach usually works well for pains associated with recent tissue damage (acute pain) but starts to fall apart when pain becomes chronic. This is because the link between pain and tissue damage (pathology) is not quite as strong as we are led to believe. For example, soldiers seriously injured in battle often report no pain for some time after the injury occurred. The link between pathology and chronic pain is particularly variable. In fact chronic pain may uncouple from the pathology that caused the pain in the first place. In essence, pain can become a disease entity in its own right.

Life experiences teach us that pain warns of tissue damage and we adapt our behaviours to avoid pain accordingly. Body parts often become “sensitive” in the presence of tissue damage so that non-painful activities become painful. Pain makes us avoid things that may hinder tissue healing so we learn to “fear” walking on a twisted ankle for example, because it provokes pain. Sensitivity associated with pathology results from the nervous system amplifying input from the site of tissue damage increasing the input to the pain producing brain — no brain, no pain. Pain resulting from sensitivity within the nervous system fades over time as tissue heals, although occasionally the nervous system remains in a persistent sensitive state despite tissue having healed. The consequence is chronic pain that has uncoupled from the original tissue damage. Pain of this nature has limited usefulness and is detrimental to well-being and reflects a dysfunctional pain system.

In such circumstances medical tests may fail to detect appreciable pathology, diagnosis may become vague, and treatment uncertain and unsuccessful. Practitioners may start to doubt the legitimacy of the person’s pain and believe that the pain is “psychogenic” (fake). This is entirely irrational because it is impossible to prove or disprove that a person is in pain, because pain is a subjective phenomenon with no objective way of measuring. The only way to gain insight into a person’s personal pain experience is through their self-report — pain is whatever the patients says it is. If a person reports that they are experiencing pain, they should be believed.

Knowledge that pain may persist without appreciable tissue damage has shifted the focus of management strategies for chronic pain that advocate progressive return to and continuation of normal activities despite the presence of pain. The challenge for the practitioner is balancing advice about under-activity, leading to disability, with over-activity leading to further pain and harm. The challenge for the patient is being able to accept and commit to a pain management plan that encourages undertaking activities in the presence of pain, because this is counterintuitive to life experiences that have taught us to avoid pain because it warns of harm. Accepting that total resolution of pain may be unlikely and committing to integrating a painful body into normal life has been shown to have a positive impact on suffering and long-term disability. In fact inactivity is a risk factor for the development of long-term pain, suffering and disability. Easy explanations of the factors contributing to chronic pain to promote a benign view of chronic pain can help individuals to change the way they think and behave about their pain. Pain management plans offering advice about the risk of harm of daily activities and self-management techniques to find solutions for pain flare ups, medication use, sleep disturbances, depression, anger, and relationship problems are becoming available.

Exercise regimes aim to get individuals to return to normal activities through stretching, strengthening, and cardiovascular fitness with the focus on progressive return to activities. Manual therapies such as massage of soft tissue and mobilization and manipulation of joints, and electrophysical agents such as transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), acupuncture, low level laser therapy, and ultrasound, are all part of the multidisciplinary pain management team’s toolkit. Clinical experience suggests that these non-pharmacological interventions are beneficial and popular with patients, although the findings of clinical research have been inconsistent. This is due to the complex nature of administering some of the interventions where optimal technique (dose) is not known.

So the puzzle of chronic pain is being unravelled with the realization that a reliance on diagnosis and treatment of pathology causing pain may not be the most effective way to help patients. We need a multidisciplinary model of care that is flexible enough to shift in emphasis from a biopsychosocial model in the acute phase to a “sociopsychobio” model in the chronic phase.

Mark Johnson is Professor of Pain and Analgesia at Leeds Metropolitan University in the UK. He is author of Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS): Research to support clinical practice.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: Doctor talking with a patient by National Cancer Institute. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Unravelling the enigma of chronic pain and its treatment appeared first on OUPblog.

With the WHO Executive Board recently adopting the resolution ‘Strengthening of palliative care as a component of integrated treatment within the continuum of care’, which is to be referred to the World Health Assembly for ratification in May, Nathan Cherny puts the current global situation in perspective and lays out the next steps needed in this crucial campaign to end suffering to millions.

By Nathan Cherny

In the curious trail that has been my life thus far, some would say that there was a certain inevitability that I would end up working for cancer patients’ right to access medication for adequate relief of their suffering. As a medical student I suffered terrible cancer-related pain from a thoracotomy to remove lung metastases for testicular cancer. As an oncologist and palliative care physician in the Middle East, my current work allows me to look after both Israeli and Palestinian patients. My profession has also taken me to caring for many “medical tourists” from Eastern Europe as well as foreign workers from Thailand, India, Nepal, and the Philippines. Oh, and I was born on Human Rights Day, 10 December 1958!

I hate pain. I am appalled by the global scope of untreated and unrelieved cancer pain. At the initiative of its Palliative Care Working Group, the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) has taken this on board as a global priority issue. ESMO facilitated the first comprehensive study to evaluate the barriers to pain relief in Europe, which highlighted the distressing situation in many Eastern European counties.

Nathan Cherny

In follow-up, a large collaborative group was formed for an even more ambitious study. The Global Opioid Policy Initiative (GOPI) combined the work and talents of ESMO, the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC), the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC), the Pain and Policies Study Group (PPSG) of the University of Wisconsin, and the World Health Organization (WHO), and 17 other leading oncology and palliative care societies worldwide.

The GOPI studied opioid availability and accessibility for cancer patients in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, Latin America, and the Caribbean. The results were published in a special supplement of the Annals of Oncology in December 2013. The seven manuscripts in the special issue highlighted the global problem of excessively restrictive regulations regarding the prescribing and dispensing of opioids — ‘catastrophe born out of good intentions’.

In order to prevent abuse and diversion, most patients with genuine need to relieve severe cancer pain cannot access the appropriate medication. Millions of people around the world end their lives racked in pain, harming not only the patients but also their families who bear witness to this torturous tragedy.

On 23 January 2014, the WHO Executive Board adopted a stand-alone resolution on palliative care which will be referred to the World Health Assembly for ratification in May 2014. This is great news for all those campaigning to improve access to medication to end suffering to millions. There is still much to be done on this long, winding road, yet we can still be proud. Thanks to our united efforts and the evidence provided by the GOPI data, our voices are being heard.

Overregulation of opioids is not the only problem impeding global relief of cancer pain. In many places around the world there is major need to: educate clinicians in the assessment and management of pain; educate the public regarding the effectiveness and safety of opioid analgesia in the management of cancer pain; and secure supplies of affordable medications.

The next steps: The GOPI Collaborative Group is now writing to Ministers of Health in the many countries where we have identified major over-regulation with a 10 point plan to help redress the problem, covering education, restrictions, limits, professional standards, monitoring, and prescription.

Tell us what actions you can take to incorporate these next steps in your country. Can you contact your Ministry of Health? What could be inspirational for others to know? We make more noise if we all shout together.

Nathan Cherny was the Chair of the ESMO Palliative Care Working Group since 2008 and has been a member of the working group since its inception in 1999. He was the main driving force in the creation of the ESMO Designated Centre of Integrated Oncology and Palliative Care Programme which was launched in 2003 and last year had its 10th Anniversary. Nathan also wrote the ESMO 2003 Position Paper: ESMO Policy on Supportive and Palliative Care. Watch the Advocacy in Action 2013 video on: Palliative Care & Quality Of Life Care: Redefining Palliative Care.

Opioid availability and accessibility for the relief of cancer pain in Africa, Asia, India, the Middle East, Latin America and the Caribbean: Final Report of the International Collaborative Project was published as an Annals of Oncology supplement in December 2013.

Annals of Oncology is a multidisciplinary journal that publishes articles addressing medical oncology, surgery, radiotherapy, paediatric oncology, basic research and the comprehensive management of patients with malignant diseases. Follow them on Twitter at @Annals_Oncology.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Photo of Nathan Cherny, via ESMO; (2) GOPI banner, via Global Opioid Policy Initiative/ESMO

The post Global Opioid Access: WHO accelerates the pace, but we still need to do more appeared first on OUPblog.