There are many aspects of Christmas that, on reflection, make little sense. We are supposed to be secular-minded, rational and grown up in the way we apprehend the world around us. Richard Dawkins speaks for many when he draws a distinction between the ‘truth’ of scientific discourse and the ‘falsehoods’ perpetuated by religion which, as he tells us in The God Delusion, “teaches us that it is a virtue to be satisfied with not understanding” (Dawkins 2006).

The post Why Christmas should matter to us whether we are ‘religious’ or not appeared first on OUPblog.

Are Christians persecuted in America? For most of us this seems like a preposterous question; a question that could only be asked by someone ginning up anger with ulterior motives. No doubt some leaders do intentionally foster this persecution narrative for their own purposes, and it’s easy to dismiss the rhetoric as hyperbole or demagoguery, yet there are conservative Christians all across the country who genuinely believe they experience such persecution.

The post Persecuted Christians in America appeared first on OUPblog.

By Grant Macaskill

In the Christian calendar, today is Ascension, the day that marks the translation of Jesus from earth to heaven. While Christmas and Easter are widely celebrated, not just by those actively involved with the church, Ascension will pass unnoticed for most.

This is paralleled both in popular and academic theology or biblical studies: while the significance of the incarnation, and of the death and resurrection of Jesus are discussed at length in relation to salvation, less tends to be said about the Ascension. It is not entirely neglected, but it does not receive the attention that it deserves and its meaning is often limited to the Ascension of Jesus to a position of rule, to the throne of God. This, though, is to neglect some important further threads in the New Testament.

My own recent thinking on the Ascension has been influenced by the work of my colleague, David Moffitt, and by numerous conversations with him as we have taught together. He has highlighted the necessity of a bodily resurrection and Ascension within the logic of the book of Hebrews, precisely because of what Jesus is described as doing in heaven to effect salvation.

This epistle represents Jesus as fulfilling the role of a high priest in the heavenly temple on which the earthly one is patterned, enacting a decisive Yom Kippur for his people and performing acts of ritual cleansing for the heavenly sanctuary, using his own blood (see Hebrews 9). Only once he has completed this work does Jesus seat himself (Heb 10:12), prior to which he stands, as all priests do in the work of the temple (Heb 10:11).

For the author of Hebrews, then, the atonement is not completed with the death or even the resurrection of Jesus; it is completed by his work in heaven. Hence, it is important that “we have a great high priest who has gone through the heavens” (Heb 4:14). That underlies his basic and remarkable hope: that we can now draw near to the presence of God, without fear as sinners (Heb 10:19-22).

Hebrews is often seen as an oddity in the New Testament, with its high priestly representation of the atonement, but there are other texts that suggest the same conceptuality is operative, if tacit, more broadly in the New Testament. The description of Jesus as ‘exalted to the right hand of God’ in Acts 2:33, for example, is echoed in Stephen’s vision of heaven in Acts 7:55-56, but there Jesus is twice specified to be ‘standing’ in that position.

Interestingly, a similar emphasis is found in the description of Jesus in Revelation: he is the Lamb “standing” between the throne and heavenly entourage (Rev 5:5). This carries a different set of connotations than does “sitting”; it suggests active service. Once this is taken into account, the priestly imagery of Hebrews begins to appear less eccentric and must instead be taken seriously as an outworking of a common early Christian presentation of atonement, one rooted in Jewish conceptuality.

Alongside this emphasis on the priestly activity of Jesus made possible by the Ascension, another theme emerges in the New Testament: the connection between the Ascension and the gift of the Holy Spirit. The book of Acts, for example, effectively begins with the Ascension of Jesus into heaven (Acts 1:9). This event is linked within the narrative to the subsequent event of Pentecost, the Jewish Feast of Weeks on which the Spirit will be poured out.

Before he ascends, Jesus tells his disciples to wait in Jerusalem for this “promise of the Father” (1:4-5), later understood to be the fulfillment of Joel 2:28ff. This same link between the Ascension of Jesus and the giving of the Spirit is reflected also in Ephesians 4:8, where Psalm 68:18 is quoted and adapted: where, in the original form of the Psalm, God ascends on high in a royal procession and receives gifts from men, here Jesus ascends and gives gifts to men.

Contextually, in Ephesians, this gift (or “grace,” Eph 4:7) comprehensively governs the communal life and mission of the church, associated with the sacramental reality of baptism: “one Lord, one baptism, one Spirit.”

A similar emphasis, though one developed in different terms, is found in John 16:7, where the departure of Jesus is the necessary condition for the coming of the Spirit. In fact, while the Ascension is seldom mentioned in the Fourth Gospel, the bodily absence of Jesus from the community is presented as key to salvation, so that even the joy of the resurrection gives way to an awareness of Jesus’s impending departure.

Thus, in John 19:17, following the resurrection, Jesus tells Mary Magdalene not to cling to him and then directs her specifically to tell the other disciples that he is to ascend. John thereby emphasizes the Ascension and, importantly, he associates it with the coming of the Spirit, by whom God’s presence will be mediated.

This last point is, perhaps, the key to the place that the Ascension has within the theology of the New Testament: access to the presence of God. The priestly work of Jesus is represented in Hebrews as allowing free access to the presence of God in the heavenly temple and is accompanied by the exhortation: “Let us draw near [to God]” (Heb 10:19-22). The gift of the Spirit, meanwhile, is presented as “God’s empowering presence,” to borrow the title of Gordon Fee’s definitive study of the Spirit in Paul’s theology.

Both reflect a powerful theological conviction that the gift of salvation is nothing less than God himself. For those theologians, academic or not, who consider the New Testament to have a normative role in Christian theology, marking Ascension ought to demand reflection on the place that such a doctrine of presence has in their own work.

Grant Macaskill is Senior Lecturer in New Testament Studies at the University of St Andrews, Scotland. His book Union with Christ in the New Testament was published by Oxford University Press (2013).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Ascension and atonement in the New Testament appeared first on OUPblog.

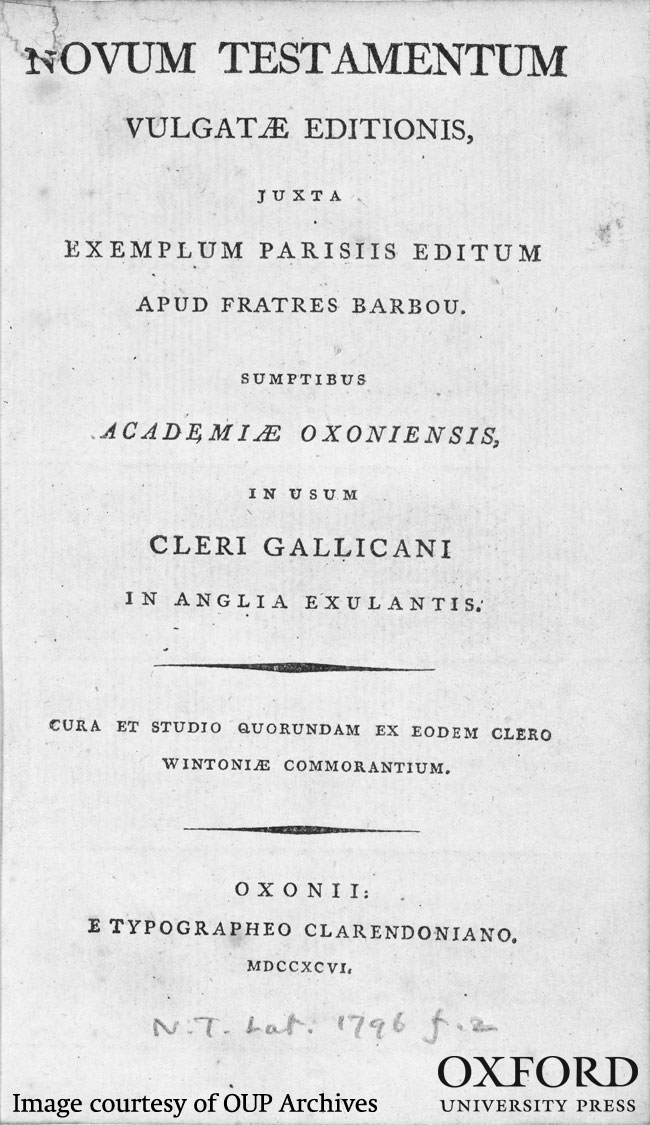

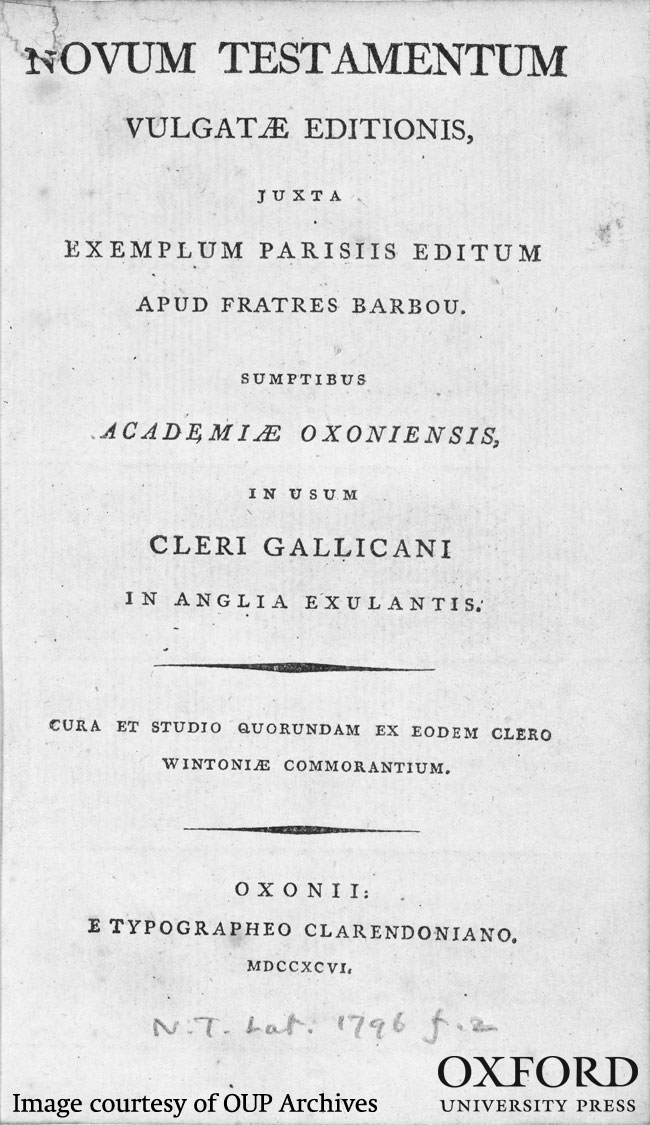

By Simon Eliot

With the French Revolution creating a wave of exiles, the Press responded with a very uncharacteristic publication. This was a ‘Latin Testament of the Vulgate Translation’ for emigrant French clergy living in England after the Revolution. In 1796, the Learned (not the Bible) side of the Press issued Novum Testamentum Vulgatae Editionis: Juxta Exemplum Parisiis Editum apud Fratres Barbou. The title page went on to declare that it had been printed at the University of Oxford for the use of French clerics who were exiled in England. This edition was based, as the title makes clear, on editions published by the Barbou brothers, which had been printed at Paris from the mid-eighteenth century onwards. This particular edition had been overseen by a number of French priests ‘living in Winchester’. The reference is to the King’s House in Winchester which, until the government converted it into barracks in 1796, was home to around 600 exiled French clergy; these were later re-housed in Reading and in Thame in the Thames valley.

A total of some 4,000 copies of this edition were printed: “That 2,000 Copies of the Lat. Vulgate Testament (besides the additional 2,000 printed by order of the Marquis of Buckingham) be forwarded to the Bishop of St . Pol de Leon to be distributed under his direction … and the remainder sold at two shillings each.”

A total of some 4,000 copies of this edition were printed: “That 2,000 Copies of the Lat. Vulgate Testament (besides the additional 2,000 printed by order of the Marquis of Buckingham) be forwarded to the Bishop of St . Pol de Leon to be distributed under his direction … and the remainder sold at two shillings each.”

Though partly an exercise in charity, it was clearly anticipated that this New Testament might also be considered a commercial proposition. The published volume appears to be a particular form of duodecimo (strictly 12o in 6s, half-sheet imposition; the paper carried a watermarked date of ‘1794’) of 473 pages with a four-page preface by the Bishop addressed to ‘Meritissime Domine Vice-Cancellarie’, in which he expressed his gratitude to the University of Oxford for its support. At the end of the text there is a brief chronological table of New Testament events, followed by an ‘Index Geographicus’. A final unnumbered leaf carries a list of errata (29 in all) which reflected a rather different approach to that adopted by the Bible Side of the Press when issuing its editions of the King James Version of the New Testament. The latter were subjected to rigorous proof reading and re-reading in order to ensure that the word of God was as free from errors as was humanly possible. This edition of a Latin text, produced in extraordinary circumstances for the consumption of mostly foreign readers, was clearly a very different kettle of fish. Additionally, in printing this edition on the Learned Side rather than the Bible Side of the Press, the Delegates culturally quarantined the production of the Vulgate text and avoided any political or religious problems that might have arisen had the privileged side of the Press undertaken it. That the very peculiar and extreme circumstances which produced this anomaly were not to be repeated was made clear 99 year later when, it having been suggested in 1895 that the Press should produce a Roman Catholic Bible, the Delegates responded that they did not ‘think it desirable that such a work should be issued with the University Press Imprint’.

Later, as the threat from Napoleonic France increased, the Press recorded certain exceptional payments in its annual accounts. These accounts included many forms of overhead costs, some a constant feature of the Press’s outgoings, such as the cost of coals and firewood (£10.17.6 in 1800) or ‘taxes to Magdalen Parish’ (£8.16.0 in the same year). Others were temporary and related to the troubled times in which they were paid. The 1805-6 accounts list the payment of a ‘Militia Tax’ of 8s6d, which went up to 17s4d in the following year. Having missed the subsequent year, the Press paid two militia rates in 1808-9 amounting to £2-7-8. In 1812-3 the rate was £1-6-0, dropping to 13s in 1813-4 before vanishing from the accounts as the threat represented by Napoleon disappeared after the battle of Waterloo.

Simon Eliot is Professor of the History of the Book in the Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London. He is general editor of The History of Oxford University Press, and editor of its Volume II 1780-1896.

With access to extensive archives, The History of Oxford University Press is the first complete scholarly history of the Press, detailing its organization, publications, trade, and international development. Read previous blog posts about the history of Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: A Vulgate New Testament printed for the use of exiled French clergy, 1796. (Bodleian, N.T.Lat. 1796 f.2, 159 x 96mm). From the History of Oxford University Press. Courtesy of OUP Archives. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post The Press stands firm against the French Revolution and Napoleon appeared first on OUPblog.

A total of some 4,000 copies of this edition were printed: “That 2,000 Copies of the Lat. Vulgate Testament (besides the additional 2,000 printed by order of the Marquis of Buckingham) be forwarded to the Bishop of St . Pol de Leon to be distributed under his direction … and the remainder sold at two shillings each.”

A total of some 4,000 copies of this edition were printed: “That 2,000 Copies of the Lat. Vulgate Testament (besides the additional 2,000 printed by order of the Marquis of Buckingham) be forwarded to the Bishop of St . Pol de Leon to be distributed under his direction … and the remainder sold at two shillings each.”