new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: monarchy, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 7 of 7

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: monarchy in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: KatherineS,

on 9/11/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

democracy,

American Revolution,

slavery,

anniversary,

VSI,

rights,

British,

citizens,

Very Short Introductions,

monarchy,

*Featured,

magna carta,

VSI online,

Arts & Humanities,

Habeas Corpus,

10 things you need to know,

Nicholas Vincent,

Add a tag

This year marks the 800th anniversary of one of the most famous documents in history, the Magna Carta. Nicholas Vincent, author of Magna Carta: A Very Short Introduction , tells us 10 things everyone should know about the Magna Carta.

The post 10 things you need to know about the Magna Carta appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Hannah Paget,

on 3/23/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

myth,

death,

British,

Tower of london,

Henry VIII,

tudor,

tudor history,

queen Elizabeth,

British history,

monarchy,

*Featured,

Queen Elizabeth I,

Spanish Armada,

UKpophistory,

Earl of Essex,

Elizabeth I and Her Circle,

English history,

Katherine Carey,

Katherine Howard,

Susan Doran,

Books,

History,

Add a tag

On 25 February 1603, Queen Elizabeth I’ s cousin and friend - Katherine Howard, the countess of Nottingham - died. Although Katherine had been ill for some time, her death hit the queen very hard; indeed one observer wrote that she took the loss ‘muche more heavyly’ than did Katherine’s husband, the Charles, Earl of Nottingham. The queen’s grief was unsurprising, for Elizabeth had known the countess longer than almost anyone else alive at that time.

The post The death of a friend: Queen Elizabeth I, bereavement, and grief appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Mark Myers,

on 6/10/2014

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

children,

History,

guys,

humor,

monty python,

royalty,

Kings,

monarchy,

It Made Me Laugh,

royals,

Add a tag

I read an interesting article about Spanish royalty this week and it got me thinking about monarchies. The article specifically mentioned the king’s 8 year-old granddaughter who was soon to become a princess. She won’t rule yet, but there have been many examples in history of children leading countries. Have you ever thought about that? I think of my kids when they were eight and would be very concerned about the consequences of them having absolute power. Worse yet, what would I have done as a reigning monarch at seven? (Or now, for that matter)

It happened all over the globe! Seriously, did any of their subjects think these good ideas?

Henry III assumed the throne of England when he was nine.

Puyi became Emperor of China when he was two years-old.

Ivan VI became the Czar of Russia at two months old

Alfonso VIII was named King of Spain the day he was born.

2 Kings 22-23 tells us of Josiah, who became King of Judah at eight.

According to Dennis the Constitutional Peasant, subjects lived in a dictatorship – “a self-perpetuating autocracy in which the working class…” Before he was repressed, Dennis was reminding us that peasants had no choice in who became their king. Sounds vaguely familiar, but I’m not political, so I will move on.

I know all of these children had advisors, but do you wonder what laws were transcribed inside the inner walls of the castle? Some might have been enacted, most were probably transcribed, agreed upon in the ruler’s presence, then discarded knowing the little king wouldn’t remember after his nap.

Edicts like these come to mind:

“The mere mention of peas, green beans, or brussel sprouts will be cause for eight lashes!”

“If I call for a toy and it is not handed to me in less than 10 seconds, the entire court shall have to walk like frogs for a day!”

“Bed time is when I fall asleep on my throne and not a moment before!”

For most child rulers, there would have been a whole legal treatise for passing gas. In fact, it would have been so overwhelming and encompassing that given the proper historical context, it could have replaced the Magna Carta as the defining law of the modern world.

We have rules in our house. You probably think that since I have all girls, our parental charter hasn’t needed gas addendums. You would be wrong. In fact, the doctor where my youngest is being treated completely shot any control over our gas emission laws with one simple, medical edict, “Gas is good.” In his opinion, it is more advantageous for the body to expel gas than hold it in. In the immortal words of Dr. Shrek, “Better out than in, I always say.”

Huh? So now, any hope we have of spending time in the absence of foul clouds is ruined. Our patient is the queen right now subscribes to the good doctor’s manner of treatment…when it suits her. We peasants bow down, joining in when nature calls under threat of law. All of us except mother, who is medically unhealthy, but socially proper. Even the doctor’s advice can’t woo her to the dark side.

In the absence of a real point to this post, I leave you with two thoughts:

1. Gas is good.

2. “Strange women, lying in ponds distributing swords is no basis for government!”

Filed under:

It Made Me Laugh

By: ChloeF,

on 9/6/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

VSI,

Europe,

Very Short Introductions,

French Revolution,

revolutions,

monarchy,

guillotine,

Reign of Terror,

bloody,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Robespierre,

1793,

french republic,

French Revolutionary Wars,

william doyle,

Add a tag

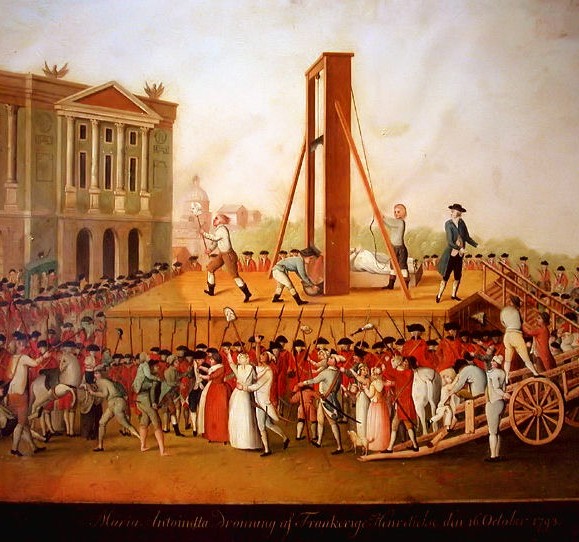

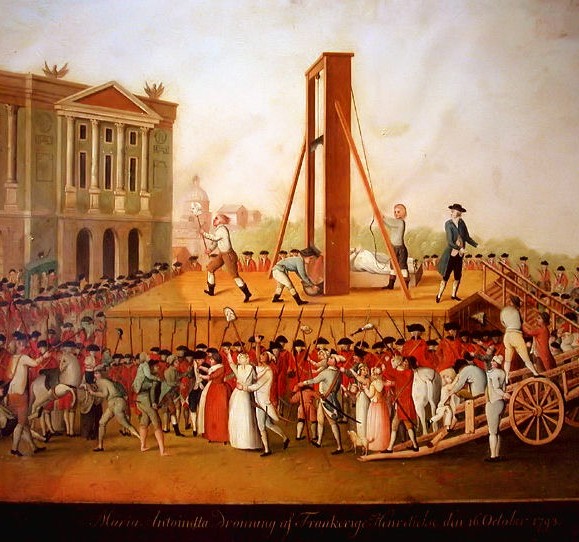

By William Doyle

Two hundred and twenty years ago this week, 5 September 1793, saw the official beginning of the Terror in the French Revolution. Ever since that time, it is very largely what the French Revolution has been remembered for. When people think about it, they picture the guillotine in the middle of Paris, surrounded by baying mobs, ruthlessly chopping off the heads of the king, the queen, and innumerable aristocrats for months on end in the name of liberty, equality, and fraternity. It was social and political revenge in action. The gory drama of it has proved an irresistible background to writers of fiction, whether Charles Dickens’s Tale of Two Cities, or Baroness Orczy’s Scarlet Pimpernel novels, or many other depictions on stage and screen. It is probably more from these, rather than more sober historians, that the English-speaking idea of the French Revolution is derived.

Unquestionably the Terror was bloody. Over 16,000 people were officially condemned to death, as many again or more probably lost their lives in less official ways, and tens of thousands were imprisoned as suspects, many of them dying in prison rather than under the blade of the guillotine. But the French Revolution did not begin with Terror, and nobody planned it in advance. Robespierre, so often (and quite wrongly) regarded as its architect, was a vocal opponent of capital punishment when the Revolution began. But revolutions, simply because they aim to destroy what went before, create enemies. In France there were probably far more losers than winners, and not all of those who lost were prepared to accept their fate. So from the start there were growing numbers of counter-revolutionaries, dreaming of overturning the new order. How were they to be dealt with?

After three years of increasing polarisation, it was decided to force everybody to choose by launching a war. In war nobody can opt out: you are on our side or on theirs, and if you’re on theirs, you’re a traitor. If the war goes badly, it becomes increasingly tempting to blame it on treason, and to crack down on everybody suspected of it. By the first quarter of 1793, the war was going badly. The first proven traitor to suffer official punishment was the king himself, overthrown in August 1792 and executed the following January. After that the new republic found itself on the defensive against most of Europe. The measures it took to organise the war effort, including conscripting young men for the armies, provoked widespread rebellion throughout the country. By the summer huge stretches of the western countryside were out of control, and major cities of the south were denouncing the tyranny of Paris. When news came in early September that Toulon, the great Mediterranean naval base, had surrendered to the British, the populace of Paris mobbed the ruling Convention and forced it to declare Terror the order of the day. It seemed the only way to defeat the republic’s internal enemies.

Many of the instruments of Terror were already in place. A revolutionary tribunal had been established in March, and the guillotine had first been used a year earlier, designed as a reliable, fast, and humane way of executing criminals. Now they were systematically turned against rebels. Most victims of the Terror died in the provinces, after forces loyal to the Convention recaptured centres of resistance. This was mopping up a civil war. The vast majority of them were not aristocrats, but ordinary people caught up in conflicts that they could not avoid. Naturally, however, it was high profile victims who caught the eye, especially when, in the early summer of 1794, political justice was centralised in Paris. Often called the ‘great’ Terror, these last few months actually represented an attempt to bring the process under control. By then people were so sickened by the bloodshed (for unlike hanging, decapitation did shed a lot of blood) that the main site of execution was moved to the suburbs. The emergency was in fact over, and repression had done its work. The fortunes of war had also turned, and French armies were winning again. So everybody was looking for ways to end an episode of which the republic was becoming increasingly ashamed. Eventually a scapegoat was found, Robespierre, who had too often stood up to defend the increasingly indefensible.

Terror had built up slowly, and the proclamation of 5 September 1793 merely confirmed what was already happening. But it ended quite suddenly in July 1794, when it was possible to pin the blame shared by many on one incautiously vocal figure and a handful of his henchmen. But however ruthlessly, Terror had saved the republic from overthrow. Nor should we forget that other combatant states at the time resorted to repression of their own. In 1798, 30,000 people died in the great Irish rebellion, in a population only a sixth that of France. The British monarchy could be every bit as ruthless as the French republic, when it had to be.

William Doyle, Professor of History, University of Bristol and author of The French Revolution: A Very Short Introduction and Aristocracy: A Very Short Introduction. Read Professor Doyle’s post on aristocracy here.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: (1) Execution of Marie Antoinette in 1793, [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons; (2) “Enemies of the people” headed for the guillotine during The Reign of Terror [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons

The post The Reign of Terror appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 2/11/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

constitution,

Japan,

emperor,

Asia,

This Day in History,

Emperor Meiji,

monarchy,

*Featured,

higher education,

chiefly,

this day in world history,

Constitution of Japan,

constitutional monarchy,

Itō Hirobumi,

the Diet,

meiji,

“enlightened,

mutsuhito,

promulgating,

Add a tag

This Day in World History

February 11, 1889

Emperor Meiji Issues New Constitution of Japan

On February 11, 1889, Japan’s Emperor Meiji furthered his plan to modernize and westernize his nation by promulgating a new constitution. The new plan of government created a western-style two-house parliament, called the Diet, and a constitutional monarchy — though one with a Japanese character.

On February 11, 1889, Japan’s Emperor Meiji furthered his plan to modernize and westernize his nation by promulgating a new constitution. The new plan of government created a western-style two-house parliament, called the Diet, and a constitutional monarchy — though one with a Japanese character.

When Prince Mutsuhito became emperor and took the ruling name Meiji (“enlightened ruler”) in 1867, he was determined to break with his late father’s traditionalist policies and embrace western ways. He took several steps in this direction. Along with creating a public school system and enacting land reforms, the Meiji emperor created government ministries.

The crowning governmental reform was the new constitution, which embraced the idea of citizen participation — though no plebiscite was held to give the public a voice in the document either as a whole or in detail. The emperor declared that the new constitution arose from his desire “to promote the welfare of, and to give development to the moral and intellectual faculties of Our beloved subjects.”

The constitution was modeled chiefly on the Prussian constitution, a fairly conservative document that subjected parliamentary rule to the power of the monarchy. Thus, the Meiji constitution began by declaring the emperor to be sovereign and “sacred and inviolable.” The emperor was named commander of the armed forces and given the power to declare war or make peace without needing to consult with the Diet.

The constitution was chiefly written by Itō Hirobumi, one of the elder statesmen who effectively ran the Japanese government. Itō and his colleagues assumed that they would be chiefly responsible for running the government and making policy and the emperor would not become involved except occasionally.

The Meiji constitution remained in force in Japan until after World War II, when a new constitution creating a stronger parliamentary system was adopted.

“This Day in World History” is brought to you by USA Higher Education.

You can subscribe to these posts via RSS or receive them by email.

By: Kirsty,

on 4/28/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

UK,

Current Events,

England,

marriage,

weddings,

royalty,

queen,

William,

elizabeth I,

monarchy,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

royal wedding,

will and kate,

kate middleton,

helen berry,

the castrato and his wife,

wills and kate,

Add a tag

By Helen Berry

The purpose of British royalty is for people to look at them. Successful monarchs throughout history have understood this basic necessity and exploited it. Elizabeth I failed to marry, and thus denied her subjects the greatest of all opportunities for royal spectacle. However, she made up for it with a queenly progress around England. As the house guest of the local gentry and nobility, she cleverly deferred upon her hosts the expense of providing bed, breakfast and lavish entertainment for her vast entourage, in return for getting up close and personal with her royal personage. It was not enough to be queen: she had to be seen to be queen. Not many monarchs pursued such an energetic itinerary or bothered to visit the farther-flung corners of their realm again (unless they proved fractious and started a rebellion). But then, most of Elizabeth’s successors over the next two hundred years were men, who could demonstrate their iconic status and personal authority, if need be, upon the battlefield (which was no mere theory: as every schoolboy or girl ought to know, George II was the last monarch to British lead troops in battle).

Towards the end of the seventeenth century, improvements in print technology and increasing freedom of the press provided a new way for British people to look at their king or queen. The rise of a mass media in Britain was made possible by the lapse of the Press Act in 1695 (the last concerted attempt by the government to censor newspapers). The Constitutional Settlement of 1689 had determined that Divine Right was not the source of the king’s authority, rather, the consent of the people through parliament. So, during the next century, from the very moment that the monarchy had started to become divested of actual power, royal-watching through the press increasingly became a spectator sport. Essentially harmless, the diverting obsession with celebrity royals proved the proverbial wisdom inherited from ancient Rome that ‘beer and circuses’ were a great way to keep people happy, and thus avoid the need to engage them with the complex and unpleasant realpolitik of the day.

It was during the long reign of George III (1760-1820) that newspapers truly started to become agents of mass propaganda for the monarchy as figureheads of that elusive concept: British national identity. The reporting of royal births, marriages and deaths became a staple of journalistic interest. Royal households had always been subject to the gaze of courtiers, politicians and visiting dignitaries, but via the press, this lack of privacy now became magnified, with public curiosity extending to the details of what royal brides wore on their wedding days. George III made the somewhat unromantic declaration to his Council in July 1761: ‘I am come to Resolution to demand in Marriage Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg Strelitz’. She was a woman ‘distinguished by every eminent Virtue and amiable Endowment’, a Protestant princess from an aristocratic German house who spoke no English before her wedding, but no matter: she was of royal blood and from ‘an illustrious Line’.

The first blow-by-blow media account of the making of a royal bride ensued, starting with the employment of 300 men to fit up the king’s yacht in Deptford to fetch Charlotte from across the Channel. Over the course of the summer in an atmosphere of anticipation at seeing their future Queen, London printsellers began cashing in, with pin-up portraits of the Princess ‘done from a Miniature’ at two shillings a time. Negotiations towards the contract of marriage were followed closely by the newsreading public during August and were concluded mid-month to general satisfaction. Finally, after two weeks of wearisome travel, on September 7th, the Princess arrived at Harwich. The St. Jam

By: Kirsty,

on 5/5/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Literature,

constitution,

UK,

Politics,

Current Events,

election,

A-Featured,

OWC,

Early Bird,

English Constitution,

walter bagehot,

bagehot,

monarchy,

Add a tag

Britain is going to the polls today for what is shaping up to be one of the closest general elections in recent years. The is even a possibility of a hung parliament, with no party winning an overall majority – we can only wait to see what Friday morning brings us. Today, though, I have this short excerpt from The English Constitution by Walter Bagehot. Written in 1867, it is generally accepted to be the best account of the history and working of the British political system ever written. As arguments raged in mid-Victorian Britain about giving the working man the vote, and democracies overseas were pitched into despotism and civil war, Bagehot took a long, cool look at the ‘dignified’ and ‘efficient’ elements which made the English system the envy of the world. The English Constitution was also the inaugural non-fiction book on the week on the Oxford World’s Classics Twitter.

‘On all great subjects,’ says Mr Mill, ‘much remains to be said,’ and of none is this more true, than of the English Constitution. The literature which has accumulated upon it is huge. But an observer who looks at the living reality will wonder at the contrast to the paper description. He will see in the life much which is not in the books; and he will not find in the rough practice many refinements of the literary theory.

It was natural––perhaps inevitable––that such an undergrowth of irrelevant ideas should gather round the British Constitution. Language is the tradition of nations; each generation describes what it sees, but it uses words transmitted from the past. When a great entity like the British Constitution has continued in connected outward sameness, but hidden inner change, for many ages, every generation inherits a series of inapt words––of maxims once true, but of which the truth is ceasing or has ceased. As a man’s family go on muttering in his maturity incorrect phrases derived from a just observation of his early youth, so, in the full activity of an historical constitution, its subjects repeat phrases true in the time of their fathers, and inculcated by those fathers, but now true no longer. Or, if I may say so, an ancient and ever-altering constitution is like an old man who still wears with attached fondness clothes in the fashion of his youth: what you see of him is the same; what you do not see is wholly altered.

There are two descriptions of the English Constitution which have exercised immense influence, but which are erroneous. First, it is laid down as a principle of the English polity, that in it the legislative, the executive, and the judicial powers, are quite divided,––that each is entrusted to a separate person or set of persons––that no one of these can at all interfere with the work of the other. There has been much eloquence expended in explaining how the rough genius of the English people, even in the middle ages, when it was especially rude, carried into life and practice that elaborate division of functions which philosophers had suggested on paper, but which they had hardly hoped to see except on paper.

Secondly, it is insisted, that the peculiar excellence of the British Constitution lies in a balanced union of three powers. It is said that the monarchical element, the aristocratic element, and the democratic element, have each a share in the supreme sovereignty, and that the assent of all three is necessary to the action of that sovereignty. Kings, lords, and commons, by this theory, are alleged to be not only the outward form, but the inner moving essence, the vitality of the constitution. A great theory, called the theory of ‘Checks and Balances,’ pervades an immense part of politica

Well. You warned this would be coming. :) I smiled when I read the title…

I know you can relate!

But does the mother of a child ruler have that authority? I know several kids who would immediately yell, “off with her head!”

i love the edicts that have been issued in the kingdom and the wisdom that flows from within )

I would love to wield power like that. What a warped kingdom.