by Deren Hansen

There's an entire set of words and phrases which have come down to us from Latin that we're slowly losing because a knowledge of ancient languages is no longer a hallmark of a good education. Even

Harry Potter hasn't been able to resurrect more than a few spell phrases from that dead language.

It's unfortunate because some ideas are best expressed in other languages. For example,

sine qua non is a Latin legal term that we must translate into the more awkward, "without which it could not be."

Sine qua non, captures the notion of something so necessary it's definitional.

I thought of that phrase when in a comment on

Non-character Antagonists and Conflict, Anne Gallagher said:

Sometimes I think dealing with internal conflict makes a better story. Character driven narrative rather than plot driven.

I'm also under the impression (in my genre I should clarify -- romance) there ALWAYS needs to be internal conflict for either the hero or heroine. One must always be conflicted by love.

Anne is right: internal conflict is the

sine qua non of story.

Some of you, particularly if you equate internal conflict with navel gazing or whiny teenagers, may roll your eyes at that assertion. You may say, for example, that your story is about action and plot and your characters neither want nor need to take time off from dodging bullets to inventory their feelings.

I understand your objection, but answer this question: what's the common wisdom about characters and flaws?

If you said (thought) something along the lines of flawed = good (i.e., relatable and interesting), perfect = bad (i.e., boring or self-indulgent), you've been paying attention. (And if your answer includes, "Mary Sue," give your self bonus points).

So why do we like flawed characters?

Is it because they allow us to feel superior?

No. It's simply that flaws produce internal conflict. That's what people really mean when they say they find flawed characters more compelling than perfect ones.

Internal conflict gives us greater insight into character. There's nothing to learn from a perfect character: if we can't compare and contrast the thought processes that early in the character's development lead to failure and later to success, we can't apply any lessons to our own behavior.

Internal conflict also creates a greater degree of verisimilitude (because who among us doesn't have a seething mass of contradictions swimming around in their brain case).

Internal conflict and the expression of character flaws arises from uncertainty. If your characters are certain about how to resolve the problem, you don't have a story you have an instruction manual.

Ergo, conflict is the

sine qua non of story.

That said, stories where conflicts at different levels reflect and reinforce each other are the most interesting because their resolution can be the most satisfying.

Deren Hansen is the author of the Dunlith Hill Writers Guides. Learn more at dunlithhill.com.

The biggest problem I have in planning a plot–still, after all these years–is that I am too nice to my characters. I can’t imagine the horrible things that need to happen, without a big struggle.

Listen up: What is the worst thing that could happen to your character? It MUST happen at the climax of the story. You can’t wimp out and make it easy on him/her. It must be totally and utterly horrible.

When your character walks through the doorway to Failure, your plot really gets going.

Of course, I mean that within the context of your story. You may have a pastel palette for this story, so the absolute worst thing might be if Jill has to clean her room. Or, you may have a palette with deep colors, including black. Jill must face the death of her best friend and she has to choose to take her place or not. Or, worse, Jill may face a life-sentence in a horrible jail, a living hell.

Whatever it is, the character MUST be faced with the worst.

Then, you can work backwards from there and create a series of scenes that lead up to that. At every step, things MUST get worse.

I also try to pair that with an internal character issue: the climax is the point where the internal and external story arcs come together. The resolution of that climax turns on some internal change in the character. The “absolute worst” thing for the character to face is determined by the internal arc. What would challenge something fundamental in your character? Jill want more than anything to gain her mother’s approval; but when her best friend is threatened, Jill goes against her mother’s commands to save her friend. She is now thinking independently.

Why is this so hard for us to do? Why are we peacemakers?

How do you overcome our “tea party” mentality so you can be brutal to your characters?

Debut Novelist Prunes her Rosebush

Introduced first in 2007, debut children’s authors have formed a cooperative effort to market their books. I featured Revision Stories from the Classes of 2k8, 2k9, 2k11 and this year, the feature returns for the Class of 2k12.

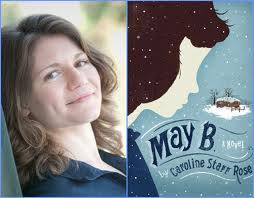

Guest post by Caroline Starr Rose, author of MAY B., MG, January 2012

Caroline Starr Rose, author of May B.

My first-round edits arrived with a four-page letter attached. In it my editor praised my writing (“This story is like a prize rosebush that needs just a bit of pruning!”) and pointed to some “thorns” that needed work.

(From Darcy: Ha! Notice Caroline’s last name.)

- More external conflict to go with all the internal business

MAY B. takes place on the 1870s Kansas frontier. Throughout much of the story, my protagonist fights to survive a blizzard. Nice external conflict, right? But much of the story is internal. There’s little dialogue, for one thing; May spends most of the story alone. She wrestles with memories of her inadequacy in school, and in her abandonment goes through stages of confusion, anger, fear and despair. But without some other tangible challenge, the story was lacking. My editor gave me a few ideas, and I latched onto one: a wolf that could terrify, challenge, and ultimately mirror my protagonist’s struggles.

- Whiny protagonist — don’t let your audience lose compassion!

I find it hard to stick with a book with a whiny character. To learn that May sometimes slipped into overkill was exactly what I didn’t want and exactly what the story didn’t need. As MAY B. is divided into three sections, my editor suggested I let May get her complaints out in the first two parts, but the third needed to be about growth, resolve, and moving forward. This advice provided a good way for me to watch my character’s progression and to temper her outbursts. Once May’s taken charge of her situation, there could be moments of doubt, but she couldn’t fall back into old behaviors. She had to push ahead.

- Ending = Deus Ex Machina

For those of you unfamiliar with this term, here’s the definition:

- (in ancient Greek and Roman drama) a god introduced into a play to resolve the entanglements of the plot.

- any artificial or improbable device resolving the difficulties of a plot.

My original ending was contrived. It just didn’t work. In order to change this, I had to weave bits into the beginning of the story to make the ending more plausible, and I had to be okay with leaving the outcome/redemption of one character, Mr. Oblinger, open ended. This was hard, as I really believed in his motives (even if they didn’t play out as he anticipated), but in keeping with an ending that wasn’t “artificial or improbable”, there was no room for this.

Tying the Revision Process Together

Throughout the revision