new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: galileo, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 7 of 7

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: galileo in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Joe Hitchcock,

on 6/16/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

NASA,

comet,

Europe,

galileo,

rosetta,

solar eclipse,

Galileo Galilei,

*Featured,

Physics & Chemistry,

Science & Medicine,

Churyumov-Gerasimenko,

European space agency,

Galileo’s visions,

Marco Piccolino,

Nicholas J. Wade,

Piercing the spheres of the heavens by eye and mind,

rosetta comet,

rosetta space program,

sun spots,

Add a tag

For some people, recent images of the Rosetta space program have been slightly disappointing. We expected to see the nucleus of the Churyumov-Gerasimenko comet as a brilliantly shining body. Instead, images from Rosetta are as black as a lump of coal. Galileo Galilei would be among those not to share this sense of disappointment.

The post From Galileo to Rosetta appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 4/25/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

OWC,

Oxford World's Classics,

Latin,

galileo,

Humanities,

italian literature,

*Featured,

Classics & Archaeology,

tasso,

classical studies,

court poetry,

Mark Davie,

the liberation of jerusalem,

torquato tasso,

tasso’s,

Poetry,

Literature,

classics,

Add a tag

By Mark Davie

Torquato Tasso, who died in Rome on 25 April 1595, desperately wanted to write a classic. The son of a successful court poet who had been brought up on the Latin classics, he had a lifelong ambition to write the epic poem which would do for counter-reformation Italy what Virgil’s Aeneid had done for imperial Rome. From his teenage years on, he worked on drafts of a poem on the first crusade which had ‘liberated’ Jerusalem from its Muslim rulers in 1099, a subject which he deemed appropriate for a Christian epic. His ambition reflected the climate in which he grew up: his formative years (he was born in 1544) saw a newly assertive orthodoxy both in literary theory (dominated by Aristotle’s Poetics, published in a Latin translation in 1536) and in religion (the Council of Trent, convened to meet the challenge of Luther’s revolt, was in session intermittently between 1545 and 1563). Those who saw Aristotle’s text as normative insisted that an epic must deal with a single historical theme in a uniformly elevated style, while the decrees emanating from Trent re-asserted the authority of the church and took an increasingly hard line against heresy. As he worked on his poem, Tasso was nervously anxious not to offend either of these constituencies.

The trouble was that his most immediate model – one whose influence he could not have ignored even if he had wanted to – was very far from conforming to the new orthodoxies. Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando furioso, a multilayered narrative loosely (very loosely) located in the historical setting of Charlemagne’s wars against the Moors in Spain, was published in 1532, and was written in more easy-going times. Ariosto could criticize the Italian rulers of his day, including the papacy, and introduce episodes into his poem which provocatively questioned conventional values, whether rational, social, or sexual, without worrying about the consequences. He could be equally casual about literary proprieties: his freewheeling poem indulged in constant romantic deviations from its main plot, such as it was, and its tone was teasingly elusive, always maintaining an ironic distance between the narrator and his subject-matter.

The trouble was that his most immediate model – one whose influence he could not have ignored even if he had wanted to – was very far from conforming to the new orthodoxies. Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando furioso, a multilayered narrative loosely (very loosely) located in the historical setting of Charlemagne’s wars against the Moors in Spain, was published in 1532, and was written in more easy-going times. Ariosto could criticize the Italian rulers of his day, including the papacy, and introduce episodes into his poem which provocatively questioned conventional values, whether rational, social, or sexual, without worrying about the consequences. He could be equally casual about literary proprieties: his freewheeling poem indulged in constant romantic deviations from its main plot, such as it was, and its tone was teasingly elusive, always maintaining an ironic distance between the narrator and his subject-matter.

The Orlando furioso was hardly a model for the poem Tasso set out to write; and yet it was hugely popular, and Tasso clearly read and admired it as much as anyone. So Tasso’s poem, as he reluctantly agreed to publish it in 1581 after 20 years of writing and rewriting, embodies the tension between his declared aim and the poem his instincts impelled him to write. It would be hard to argue that the Gerusalemme liberata (The Liberation of Jerusalem) is an unqualified success as a celebration of counter-reformation Christianity; instead it is something much more interesting, an expression of the inner contradictions of late sixteenth-century culture as they were felt by a sensitive – sometimes hyper-sensitive – and gifted poet.

Some of Tasso’s drafts had leaked out during the poem’s long gestation and had been published without his consent, so the poem was eagerly awaited, and it immediately had its devotees. Not everyone, however, was impressed. Among those who were not was Galileo, who wrote a series of acerbic notes on the poem some time before 1609. His criticisms are mostly on details of language and style, but in one revealing comment he compares Tasso’s poetic conceits to ostentatiously difficult dance steps, which are pleasing only if they are ‘carried through with supreme accomplishment, so that their gracefulness overrides their affectation’. Grazia versus affettazione: the terms are taken from Castiglione’s Book of the Courtier, that indispensable guide to Renaissance manners which decreed that the courtier’s accomplishments should be displayed with an appearance of effortless nonchalance. Tasso’s offence against courtly manners was that he tried too hard.

The Gerusalemme liberata is indeed full of unresolved tensions – between historical chronicle and romantic fantasy, sensuality and solemnity, the broad sweep of history and the playing out of individual passions. They are what bring the poem to life today, long after the crusades have lost their appeal as a topic for celebration. Galileo rebukes one of Tasso’s heroes for being too easily deflected from his duty by love: ‘Tancredi, you coward, a fine hero you are! You were the first to be chosen to answer Argante’s challenge, and then when you come face to face with him, instead of confronting him you stop to gaze on your lady love’. Tancredi does admittedly cut a rather ludicrous figure when he is transfixed by catching sight of Clorinda just as he is about to accept the Saracen champion’s challenge, but what Galileo didn’t realise was that the very vehemence of his indignation was a testimony to the effectiveness of Tasso’s writing. Plenty of poets wrote about how love mocks the pretentions of would-be heroes, but few dramatised it so effectively – and only Tasso could have written the scene, memorably set to music by Monteverdi, where Tancredi meets Clorinda in single combat, her identity (and her gender) concealed under a suit of armour, and recognises her only when he has mortally wounded her and he baptises her before she dies in his arms.

Galileo was wrong about Tasso’s poem. The very qualities which he deplored make it a classic which inspired poets from Spenser and Milton to Goethe and Byron, composers from Monteverdi to Rossini, and painters from Poussin to Delacroix, and which is still a compelling read today.

Mark Davie taught Italian at the Universities of Liverpool and Exeter. His interests focus particularly on the relation between learned and popular culture, and between Latin and the vernacular, in Italy in the Renaissance. In Oxford World’s Classics he has written the introduction and notes to Max Wickert’s translation of The Liberation of Jerusalem, and has translated (with William R. Shea) the Selected Writings of Galileo.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog. Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Statue of Torquato Tasso by Luigi Chiesa. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post How to write a classic appeared first on OUPblog.

By: KatherineS,

on 4/6/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

persecution,

galileo,

Galileo Galilei,

lichtenberg,

*Featured,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

Bertolt Brecht,

werner,

Arpan Banerjee,

History of Radiology,

Moses Swick,

radiology,

The Life of Galileo,

Werner Forssmann,

Wilhelm Röntgen,

forssmann,

swick,

by nfejza,

brecht’s,

Books,

History,

Add a tag

By Arpan Banerjee

Recently I had the good fortune to see an excellent production of Bertolt Brecht’s play The Life of Galileo at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre. Brecht has a tenuous connection with the medical profession; he registered in 1917 to attend a medical course in Munich and found himself drafted into the army, serving in a military VD clinic for a short while before the end of the war. Brecht’s main interest, however, was drama (in 1918 he wrote his first play Baal) and it was in this field that he made his lasting contribution.

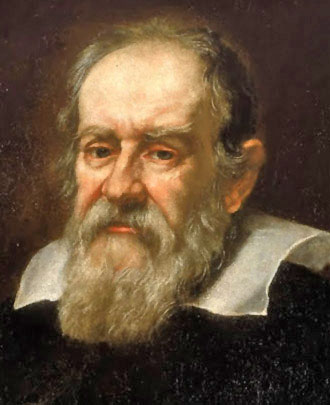

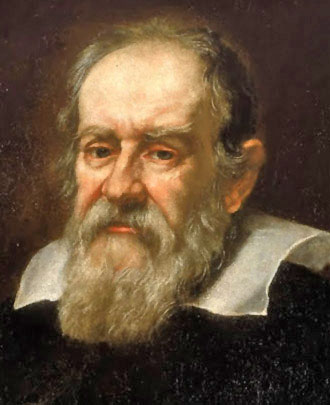

Galileo Galilei

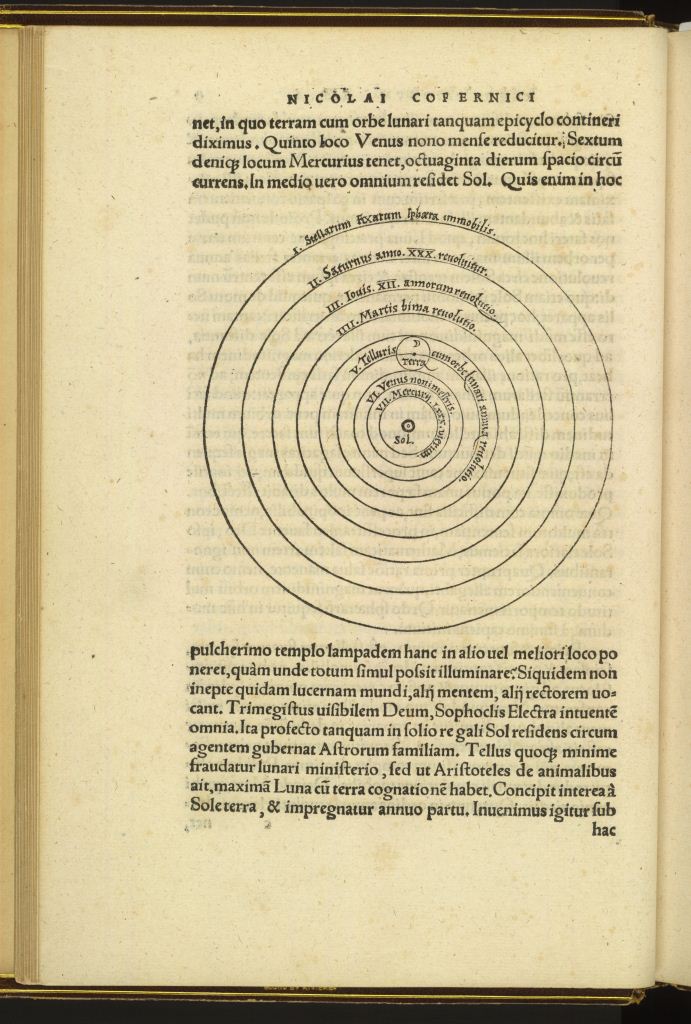

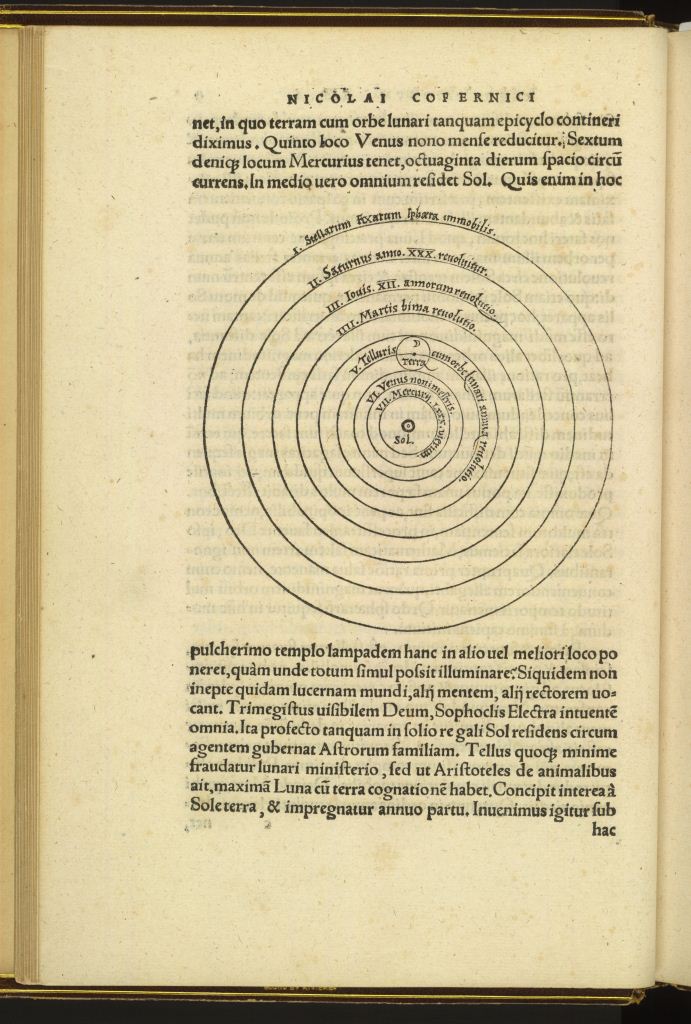

Galileo was persecuted by the Church and the established authorities for his scientific research. His major crime was using his telescope to confirm the Copernican model of the Sun being at the centre of the solar system with the earth revolving around it. This challenged the cultural consensus and the leaders of the day were not prepared to listen to scientific evidence which challenged old dogmas. Galileo was interrogated in the Vatican, tortured, and forced to retract his theories.

The medical profession has also seen more than its fair share of persecution. I will illustrate with two examples in the relatively new speciality of radiology. The people concerned were not radiologists as such but were conducting pioneering research in imaging. Wilhelm Rötgen, the German physicist who first discovered x-rays in 1895, did himself meet relatively few obstacles regarding the dissemination of his thoughts and findings. But Werner Forssmann, a physician from the small town of Eberswalde in Germany, was not so lucky. In 1929, it is claimed, Forsmann performed the procedure of catheterisation of the heart upon himself and incurred the wrath of his boss as a result. He was sacked and had to switch from a career in cardiology to urology.

Forssmann was to have the last laugh a quarter century later when he shared the 1956 Nobel Prize for his contribution to cardiac catheterisation. This is now a commonplace procedure worldwide.

Werner Forssmann

The next case concerns the plight of Moses Swick, an American urology intern who went to Germany in 1928 to work with Professor Lichtenberg in Berlin. Swick performed scientific studies of a new intravenous contrast agent which would enable visualisation of the renal tract. He and Professor Lichtenberg fell out about who should be given the accolade for the discovery; Lichtenberg stole the limelight and was invited to talk about intravenous urography at the American Urological Association Scientific meeting. For 35 years Swick worked as an urologist in New York until in 1966 it was realised that he had been the victim of injustice and his role in the discovery was belatedly recognised.

These stories are examples where justice prevailed in the end. There are several others which did not and still do not realise fair outcomes.

Arpan K Banerjee qualified in medicine from St Thomas’s Hospital Medical School in London, UK and trained in Radiology at Westminster Hospital and Guys and St Thomas’s Hospital. In 2012 he was appointed Chairman of the British Society for the History of Radiology of which he is a founder member and council member. In 2011 he was appointed to the scientific programme committee of the Royal College Of Radiologists, London. He is the author/co-author of six books including the recent The History of Radiology. Read his previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Galileo, public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Wilhelm Röntgen, by NFejza, CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Werner Forssmann nobel, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Persecution in medicine appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/8/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

shakespeare,

Geography,

renaissance,

mars,

John Donne,

astrology,

astronomy,

marlowe,

place of the year,

Copernicus,

john evelyn,

galileo,

Humanities,

POTY,

Social Sciences,

Kepler,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Middleton,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

OSEO,

Place of the Year 2012,

poty 2012,

Claude Mylon,

Francois de Verdus,

Gascoigne,

Girolamo Preti,

John Skelton,

Marilyn Deegan,

Robert Burton,

Samuel Sorbière,

Thomas Hobbes,

Thomas Stanley,

William Lilly,

Literature,

Add a tag

By Marilyn Deegan

The new discoveries of the Mars rover Curiosity have greatly excited the world in the last few weeks, and speculation was rife about whether some evidence of life has been found. (In actuality, Curiosity discovered complex chemistry, including organic compounds, in a Martian soil analysis.)

Why the excitement? Well, astronomy, cosmology, astrology, and all matters to do with the stars, the planets, the universe, and space have always fascinated humankind. Scientists, astrologers, soothsayers, and ordinary people look up to the heavenly bodies and wonder what is up there, how far away, whether there is life out there, and what influence these bodies have upon our lives and our fortunes. Were we born under a lucky star? Will our horoscope this week reveal our future? What is the composition of the planets?

Astronomy is one of the oldest natural sciences, but it was the invention of the telescope in the early 17th century that advanced astronomy into a science in the modern sense of the word. Throughout the course of the 16th and 17th centuries, Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, and others challenged the established Ptolemeic cosmology, and put forth the theory of a heliocentric solar system. The Church found a heliocentric universe impossible to accept because medieval Christian cosmology placed earth at the centre of the universe with the Empyrean sphere or Paradise at the outer edge of the circle; in this model, the moral universe and the physical universe are inextricably linked. (This is a model that is typified in Dante’s Divine Comedy.)

Authors from John Skelton (1460-1529) to John Evelyn (1620-1706) lived in this same period of great change and discovery, and we find a great deal of evidence in Renaissance writings to show that the myths, legends, and scientific discoveries around astronomy were a significant source of inspiration.

The planets are of course not just planets: they are also personifications of the Greek and Roman gods; Mars is a warlike planet, named after the god of war. Because of its red colour the Babylonians saw it as an aggressive planet and had special ceremonies on a Tuesday (Mars’ day; mardi in French) to ward off its baleful influence. We find much evidence of the warlike nature of Mars in writers of the period: Thomas Stanley’s 1646 translation Love Triumphant from A Dialogue Written in Italian by Girolamo Preti (1582-1626) is a verbal battle between Venus and her accompanying personifications (Love, Beauty, Adonis) and Mars (who was one of her lovers) and his cohort concerning the superior powers of love and war. Venus wins out over the warlike Mars: a familiar image of the period.

John Lyly’s play The Woman in the Moon (c.1590-1595) also personifies the planets and plays on the traditional notion that there is a man in the moon. Lyly’s use of the planets is thought to reflect the Elizabethan penchant for horoscope casting. The warlike Mars versus Venus trope is common throughout the period, and it appears in the works of Shakespeare, Marlowe, Middleton, Gascoigne, and most of their contemporaries. A search in the current Oxford Scholarly Editions Online collection for Mars and Venus reveals almost 300 examples. Many writers of the period also refer to astrological predictions; Shakespeare in Sonnet 14 says:

Not from the stars do I my judgement pluck,

And yet methinks I have astronomy,

But not to tell of good or evil luck,

Of plagues, of dearths, or seasons’ quality;

This is thought to be a response to Philip Sidney’s quote in ‘Astrophil and Stella’ (26):

Who oft fore-judge my after-following race,

By only those two starres in Stella’s face.

Thomas Powell (1608-1660) suggests astrological allusions in his poem ‘Olor Iscanus’:

What Planet rul’d your birth? what wittie star?

That you so like in Souls as Bodies are!

…

Teach the Star-gazers, and delight their Eyes,

Being fixt a Constellation in the Skyes.

While there is still much myth and metaphor pertaining to heavenly bodies in 17th century literature, there is increasing scientific discussion of the positions of the planets and their motions. To give just a few examples, Robert Burton’s 1620 Anatomy of Melancholy discusses the new heliocentric theories of the planets and suggests that the period of revolution of Mars around the sun is around three years (in actuality it is two years).

In his Paradoxes and Problemes of 1633, John Donne in Probleme X discusses the relative distances of the planets from the earth and quotes Kepler:

Why Venus starre onely doth cast a Shadowe?

Is it because it is neerer the earth? But they whose profession it is to see that nothing bee donne in heaven without theyr consent (as Kepler sayes in himselfe of all Astrologers) have bidd Mercury to bee nearer.

The editor’s note suggests that Donne is following the Ptolemaic geocentric system rather than the recently proposed heliocentric system. In his Devotions upon Emergent Occasions of 1623 Donne castigates those who imagine that there are other peopled worlds, saying:

Men that inhere upon Nature only, are so far from thinking, that there is anything singular in this world, as that they will scarce thinke, that this world it selfe is singular, but that every Planet, and every Starre, is another world like this; They finde reason to conceive, not onely a pluralitie in every Species in the world, but a pluralitie of worlds;

There are also a number of letters written in the 1650s and 1660s between Thomas Hobbes and Claude Mylon, Francois de Verdus, and Samuel Sorbière concerning the geometry of planetary motion.

William Lilly’s chapter on Mars in his Christian Astrology (1647), is a blend of the scientific and the metaphoric. He is correct that Mars orbits the sun in around two years ‘one yeer 321 dayes, or thereabouts’, and he lists in great detail the attributes of Mars: the plants, sicknesses, qualities associated with the planet. And he states that among the other planets, Venus is his only friend.

There are few areas of knowledge where myth, metaphor, and science are as continuously connected as that pertaining to space and the universe. Our origins, our meaning systems, and our destinies — whatever our religious beliefs — are bound up with this unimaginably large emptiness, furnished with distant bodies that show us their lights, lights which may have been extinguished in actuality millenia ago. Only death is more mysterious, and many of our beliefs about life and death are also bound up with the mysteries of the universe. That is why we remain so fascinated with Mars.

Marilyn Deegan is Professor Emerita in the Department of Digital Humanities at King’s College, University of London. She has published widely on textual editing and digital imaging. Her book publications include Digital Futures: Strategies for the Information Age (with Simon Tanner, 2002), Digital Preservation (edited volume, with Simon Tanner, 2006), Text Editing, Print and the Digital World (edited volume, with Kathryn Sutherland, 2008), and Transferred Illusions: Digital Technology and the Forms of Print (with Kathryn Sutherland, 2009). She is editor of the journal Literary and Linguistics Computing and has worked on numerous digitization projects in the arts and humanities. Read Marilyn’s blog post where she looks at the evolution of electronic publishing.

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO) is a major new publishing initiative from Oxford University Press. The launch content (as at September 2012) includes the complete text of more than 170 scholarly editions of material written between 1485 and 1660, including all of Shakespeare’s plays and the poetry of John Donne, opening up exciting new possibilities for research and comparison. The collection is set to grow into a massive virtual library, ultimately including the entirety of Oxford’s distinguished list of authoritative scholarly editions.

Oxford University Press’ annual Place of the Year, celebrating geographically interesting and inspiring places, coincides with its publication of Atlas of the World – the only atlas published annually — now in its 19th Edition. The Nineteenth Edition includes new census information, dozens of city maps, gorgeous satellite images of Earth, and a geographical glossary, once again offering exceptional value at a reasonable price. Read previous blog posts in our Place of the Year series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Written in the stars appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 9/7/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

professor,

Dante,

philosopher,

galileo,

Humanities,

italian literature,

*Featured,

Physics & Chemistry,

Science & Medicine,

galileo’s,

Ariosto,

Commedia dell’Arte,

courtier,

Dialogue on the two chief world systems,

Gerusalemme Liberata,

John L. Heilbron,

Orlando Furioso,

Petrarch,

Tasso,

littérateur,

Literature,

Add a tag

By John L. Heilbron

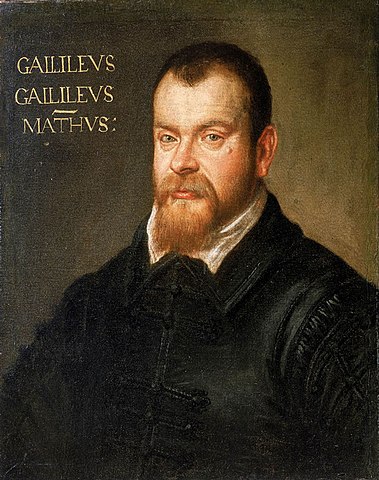

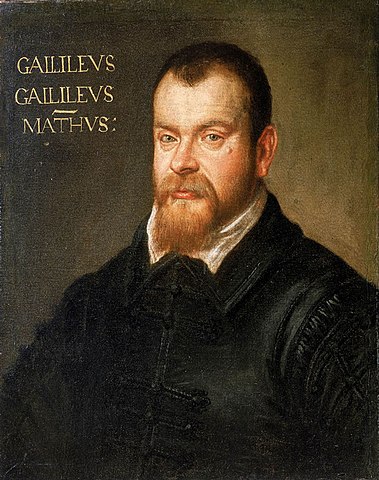

Galileo Galilei by Domenico Tintoretto, 1605-1607.

Galileo is not a fresh subject for a biography. Why then another? The character of the man, his discovery of new worlds, his fight with the Roman Catholic Church, and his scientific legacy have inspired many good books, thousands of articles, plays, pictures, exhibits, statues, a colossal tomb, and an entire museum. In all this, however, there was a chink.

Galileo cultivated an interest in Italian literature. He commented on the poetry of Petrarch and Dante and imitated the burlesques of Berni and Ruzzante. His special favorite was Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, which he prized for its balance of form, wit, and nonsense. His special dislike was Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata (The Liberation of Jerusalem), which violated his notions of heroic behavior and ordinary prosody. Galileo tried his hand at sonnets, sketched plots in the style of the Commedia dell’Arte, and delivered much of his science in dialogues.

The literary side of Galileo is not a discovery; a large specialist literature is devoted to it. But there is a gap in scholarship between the literary Galileo and the rest of him. How were his choices in science and literature complementary and reinforcing? What might be learned from his pronounced literary preferences about the unusual and creative features of his physics? How does Galileo’s praise of Ariosto and criticism of Tasso, on the one hand, parallel his embrace of Archimedes and rejection of Aristotle on the other?

Usually Galileo enters his biography already possessed of most of the convictions and concerns that prompted his discoveries and precipitated his troubles. One reason for endowing him with such precocity is that the documentation for his life before the age of 35 is relatively sparse. In contrast, a quantity of reliable information exists for his later life, after he had transformed a popular toy into an astronomical telescope and himself from a Venetian professor into a Florentine courtier (that happened in 1609/10 when he was 45). By paying attention to his early literary pursuits and associates, however, it is possible to tease out enough about his circumstances as a young man to give him a character different from the cantankerous star-gazer, abstract reasoner, and scientific martyr he became.

A quarrelsome philosopher, half-professor and half-courtier, whose discoveries refashioned the heavens and whose provocative use of them brought him into hopeless conflict with authority, is an attractive subject for portraiture. Add Galileo’s life-long engagement with imaginative writing and the would-be portraitist has his or her hands full. But the resultant picture, even if well-executed, would be a caricature. Galileo initially made his living and gained his reputation as a mathematician. Leave out his mathematics and you may have a compelling character, but not Galileo.

The mathematician and the littérateur have different ways of arguing. To fit together, one sometimes must give way. Galileo’s great polemical work, Dialogue on the two chief world systems, which misleadingly resembles a work of science, frequently privileges rhetoric over mathematics. When the scientific arguments are weakest, the two protagonists in the Dialogue who represent Galileo (his dead buddies Salviati and Sagredo) outdo one another in praising his contrivances and in twitting the third party to the discussions, the bumbling good-natured school philosopher Simplicio, for ignorance of geometry.

The mathematical inventions of the Dialogue that Galileo’s creatures noisily rate as unsurpassed marvels are precisely those that have given commentators the greatest difficulty. These inventions are extremely clever but evidently flawed if taken to be true of the world in which we live. Commentators tend either to interpret the cleverness as shrewd anticipations of later science or to condemn the shortfalls as just plain errors. From my point of view, these marvels should be interpreted as literary devices, conundrums, extravaganzas, inventions too good not to be true in some world if not in ours. They are hints at the form, not the completed ingredients, of a mathematical physics. Galileo’s old Dialogue and today’s Physical Review belong to different genres. Unfortunately, just as the Dialogue was not intended to meet the requirements of accuracy and verisimilitude of modern science journals, so the journals don’t reward the sort of wit and style with which Galileo brought together his literary aspirations, polemical agenda, and scientific insights.

John Heilbron is Professor of History and Vice Chancellor Emeritus of the University of California at Berkeley. One of the most distinguished historians of science, his books include Galileo, The Sun in the Church (a New York Times Notable Book) and The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

By: Alice,

on 2/13/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

planets,

This Day in History,

Europe,

copernicus,

martin luther,

Inquisition,

galileo,

Galileo Galilei,

Pope Urban VIII,

John Calvin,

*Featured,

Physics & Chemistry,

higher education,

Science & Medicine,

this day in world history,

Copernican theory,

Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems,

Nicolas Copernicus,

copernican,

galileo’s,

1633,

summoned,

Add a tag

This Day in World History

February 13, 1633

Galileo arrives in Rome for trial before Inquisition

Source: Library of Congress.

Sixty-nine years old, wracked by sciatica, weary of controversy, Galileo Galilei entered Rome on February 13, 1633. He had been summoned by Pope Urban VIII to an Inquisition investigating his

Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems. The charge was heresy. The cause was Galileo’s support of the Copernican theory that the planets, including Earth, revolved around the sun.

Nicolas Copernicus had published his heliocentric theory in 1543. His ideas were condemned by religious leaders — not only Catholic ones but also Protestants Martin Luther and John Calvin — because they contradicted the Bible. Slowly, though, astronomers began to accept the sun-centered universe.

Galileo’s own acceptance, forged in the 1590s, grew stronger in 1609, when he used a new invention, the telescope, to study the planets. Discovering that the Moon had craters, Jupiter was orbited by moons, and Venus had phases like the Moon, he rejected the accepted belief that the heavens were fixed, perfect, and revolving around Earth.

Church authorities, however, objected to a 1613 letter he wrote supporting the Copernican theory. At a hearing, he was told not to actively promote Copernican ideas. A document placed in the records of the proceeding went further, saying he was ordered never to discuss the theory in any way, but evidence suggests that Galileo’s understanding the document was planted after the meeting by enemies.

By the late 1620s, Galileo believed that Pope Urban would be more open to his ideas than earlier popes. He wrote the Dialogue as a conversation between a Copernican and an adherent of the Church’s geocentric theory, hoping to escape condemnation by presenting both views. The ploy failed, and he was summoned. The panel of cardinals decided to ban his book, force him to abjure Copernican ideas, and sentence him to imprisonment. A few months later, the old man was released to his home, where he lived until 1642.

“This Day in World History” is brought to you by USA Higher Education.

You can subscribe to these posts via RSS or receive them by email.

By: Lauren,

on 1/28/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Religion,

church,

christianity,

Europe,

catholic,

galileo,

*Featured,

john heilbron,

Philosophy,

pope,

Add a tag

By John Heilbron

What Galileo believed about providence, miracles, and salvation, is hard to say. It may not matter. Throughout his life he functioned as the good Catholic he claimed to be; and he received many benefits from the church before and after the affair that brought him to his knees before the Holy Inquisition in 1633.

First among these benefits was education. Galileo studied for a few years at the convent of Vallombrosa (a Benedictine order) near Florence. He loved the place and had entered his novitiate when his father removed him from the temptation. Later the Vallombrosans gave him his first important job teaching mathematics. He probably lived briefly at the Benedictine convent of Santa Giustina in Padua just after taking up a professorship at Venice’s university there in 1592. He may have taught at Santa Giustina and from its ranks recruited his most faithful disciple, Dom Benedetto Castelli.

The largest and ablest collection of mathematicians in Italy belonged to the Society of Jesus. When he started serious study of mathematics, Galileo sought and obtained the advice and approval of their leader, Father Christopher Clavius. He had to break off relations in 1606, when the Venetian state expelled the Jesuits from its territories. Galileo restored the connection soon after returning to Florence in 1610 as “Mathematician and Philosopher to the Grand Duke of Tuscany.” Again he had an urgent need for Clavius’ endorsement. The astonishing discoveries he had made in 1609/10 by turning his telescope on the heavens challenged credulity. By the end of 1610 he had the confirmation he wanted. Clavius’ group of mathematicians invited him to their headquarters in Rome to celebrate the “message from the stars,” as Galileo had entitled the book in which he had announced his discoveries, and to toast the messenger.

Galileo’s other benefits from the Church included the large salary he enjoyed as court mathematician and philosopher, which came from ecclesiastical revenues, and a papal pension for his son. The son declined on discovering that its beneficiary had to wear a tonsure, and Galileo, having no such reservation, took it himself. In the hope of relieving his chronic illnesses, he made pilgrimages to Loreto. To relieve himself of his two illegitimate daughters, he put them in a nunnery. When old and blind and confined to his villa, members of religious orders comforted and read to him. And throughout his life he had many friends, disciples, and patrons among ecclesiastics.

His late-in-life comforters were not Jesuits. Obliged to teach the physics of Aristotle, in which the earth stands still at the center of the world, they could not endorse the Copernican system, which Galileo believed his discoveries proved. That did not stop them from becoming experts in telescopic astronomy. Galileo did not like the competition and attacked the Jesuits unfairly. That was a mistake. They did not help him when he ran into an order of priests who did not like mathematics. These were the Dominicans, who ran the machinery of the Inquisition.

Some of their firebrands preached that since Copernican notions conflicted with Joshua’s order to the sun to stand still, they might be heretical. Galileo hurried to Rome in 1615 to clear himself and Copernicanism. Early in 1616 the Inquisition found that Copernicanism was contrary to scripture and philosophically absurd; the Congregation of the Index thereupon banned Copernicus’ masterpiece pending correction and other works altogether; but it did not mention Galileo. Instead, on papal orders, the chief theologian of the Inquisition, the Jesuit Cardinal (now Saint) Robert Bellarmine, summoned Galileo to hear the decree of the Index and to receive, in private, a personal injunction not to teach or hold the Copernican theory in any way whatsoever.

Galileo obeyed this instruction unti

The trouble was that his most immediate model – one whose influence he could not have ignored even if he had wanted to – was very far from conforming to the new orthodoxies. Ludovico Ariosto’s

The trouble was that his most immediate model – one whose influence he could not have ignored even if he had wanted to – was very far from conforming to the new orthodoxies. Ludovico Ariosto’s