new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: cognitive psychology, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 10 of 10

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: cognitive psychology in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Emily Gorney,

on 4/15/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

problem solving,

self-help,

cognitive psychology,

*Featured,

Developmental Psychology,

Psychology & Neuroscience,

Arnaud Chevallier,

Strategic Thinking in Complex Problem Solving,

Books,

Personal Development,

Data,

research,

Add a tag

Solving complex problems requires, among other things, gathering information, interpreting it, and drawing conclusions. Doing so, it is easy to tend to operate on the assumption that the more information, the better. However, we would be better advised to favor quality over quantity, leaving out peripheral information to focus on the critical one.

The post Looking for information: How to focus on quality, not quantity appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Emily Gorney,

on 3/18/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

foster care,

orphan,

cognitive psychology,

international adoption,

Institutional care,

child-welfare,

emotional neglect,

Rebecca Compton,

Books,

adoption,

Social Work,

*Featured,

Psychology & Neuroscience,

Adoption Beyond Borders,

adoptive parent,

parenting,

Add a tag

More than 70 years ago, psychologist Rene Spitz first described the detrimental effects of emotional neglect on children raised in institutions, and yet, today, over 7 million children are estimated to live in orphanages around the world. In many countries, particularly in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, the rate of institutionalization of poor, orphaned, and neglected children has actually increased in recent years, according to UNICEF.

The post The consequences of neglect appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Emily Gorney,

on 11/27/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

brain,

genetic engineering,

neuroscience,

cognitive psychology,

biotechnology,

*Featured,

Science & Medicine,

Psychology & Neuroscience,

Francisco Mora,

Art Aesthetics and the Brain,

Camilo Jose Cela Conde,

Joseph P. Huston,

Luigi F. Agnati,

Marcos Nadal,

neuroculture,

Add a tag

Are we at the birth of a new culture in the western world? Are we on the verge of a new way of thinking? Both humanistic and scientific thinkers suggest as much.

The post Is neuroculture a new cultural revolution? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Franca Driessen,

on 9/20/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

computer science,

cognition,

cognitive psychology,

*Featured,

computation,

philosophy of science,

Arts & Humanities,

John Searle,

Gualtiero Piccinini,

hilary putnam,

ian hinckfuss,

neal anderson,

physical computation,

Books,

Philosophy,

computer,

Add a tag

Once again, searching for unconventional computing methods as well as for a neurocomputational theory of cognition requires knowing what does and does not count as computing. A question that may appear of purely philosophical interest — which physical systems perform which computations — shows up at the cutting edge of computer technology as well as neuroscience.

The post The philosophical computer store appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Helena Palmer,

on 8/1/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Philosophy,

Memory,

consciousness,

mind,

prejudice,

cognitive psychology,

Bias,

Conscious Mind,

*Featured,

cognitive science,

Working Memory,

Psychology & Neuroscience,

cognitive control,

Arts & Humanities,

Cognitive Philosophy,

conscious thought,

Implicit Attitudes Test,

Peter Carruthers,

Philosophical Thought,

The Centered Mind,

Unconscious thought,

Add a tag

Influenced by the discoveries of cognitive science, many of us will now accept that much of our mental life is unconscious. There are subliminal perceptions, implicit attitudes and beliefs, inferences that take place tacitly outside of our awareness, and much more.

The post Who’s in charge anyway? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Ella Sharp,

on 3/19/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

q&a,

neuroscience,

consciousness,

cognitive psychology,

*Featured,

Science & Medicine,

Psychology & Neuroscience,

Behavioral Methods in Consciousness Research,

Morten Overgaard,

neuropsychology,

Add a tag

Why are we conscious? How can it be that physical processes in the brain seem to be accompanied with subjective experience? As technology has advanced, psychologists and neuroscientists have been able to observe brain activity. But with an explosion in experiments, methods, and measurements, there has also been great confusion.

The post Morten Overgaard on consciousness appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Meredith Sneddon,

on 8/21/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

computing,

cognitive psychology,

*Featured,

Science & Medicine,

Psychology & Neuroscience,

visual processing,

Experimental vision,

Li Zhaoping,

Understanding vision,

Books,

Data,

vision,

Theory,

models,

Add a tag

About half a century ago, an MIT professor set up a summer project for students to write a computer programme that can “see” or interpret objects in photographs. Why not! After all, seeing must be some smart manipulation of image data that can be implemented in an algorithm, and so should be a good practice for smart students. Decades passed, we still have not fully reached the aim of that summer student project, and a worldwide computer vision community has been born.

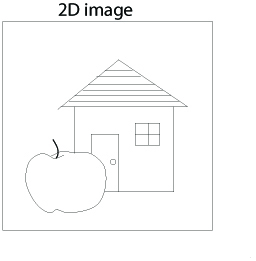

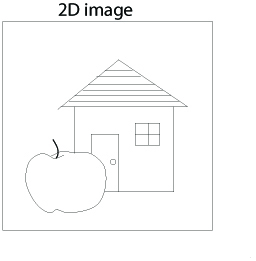

We think of being “smart” as including the intellectual ability to do advanced mathematics, complex computer programming, and similar feats. It was shocking to realise that this is often insufficient for recognising objects such as those in the following image.

Image credit: Fig 5.51 from Li Zhaoping,

Understanding Vision: Theory Models, and Data

Can you devise a computer code to “see” the apple from the black-and-white pixel values? A pre-school child could of course see the apple easily with her brain (using her eyes as cameras), despite lacking advanced maths or programming skills. It turns out that one of the most difficult issues is a chicken-and-egg problem: to see the apple it helps to first pick out the image pixels for this apple, and to pick out these pixels it helps to see the apple first.

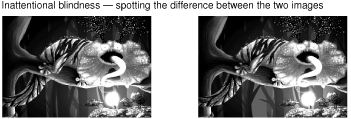

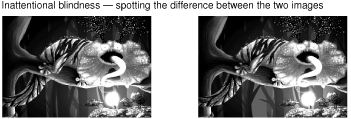

A more recent shocking discovery about vision in our brain is that we are blind to almost everything in front of us. “What? I see things crystal-clearly in front of my eyes!” you may protest. However, can you quickly tell the difference between the following two images?

Image credit: Alyssa Dayan, 2013 Fig. 1.6 from Li Zhaoping

Understanding Vision: Theory Models, and Data. Used with permission

It takes most people more than several seconds to see the (big) difference – but why so long? Our brain gives us the impression that we “have seen everything clearly”, and this impression is consistent with our ignorance of what we do not see. This makes us blind to our own blindness! How we survive in our world given our near-blindness is a long, and as yet incomplete, story, with a cast including powerful mechanisms of attention.

Being “smart” also includes the ability to use our conscious brain to reason and make logical deductions, using familiar rules and past experience. But what if most brain mechanisms for vision are subconscious and do not follow the rules or conform to the experience known to our conscious parts of the brain? Indeed, in humans, most of the brain areas responsible for visual processing are among the furthest from the frontal brain areas most responsible for our conscious thoughts and reasoning. No wonder the two examples above are so counter-intuitive! This explains why the most obvious near-blindness was discovered only a decade ago despite centuries of scientific investigation of vision.

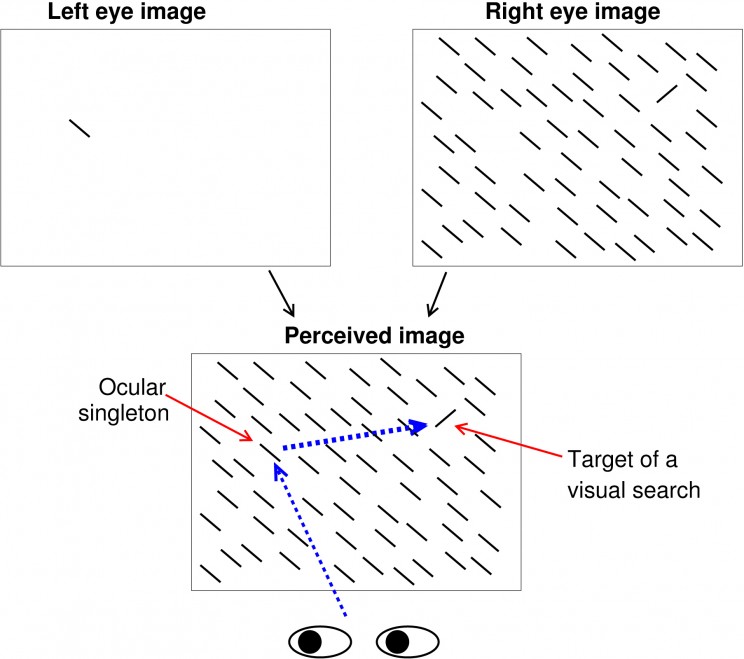

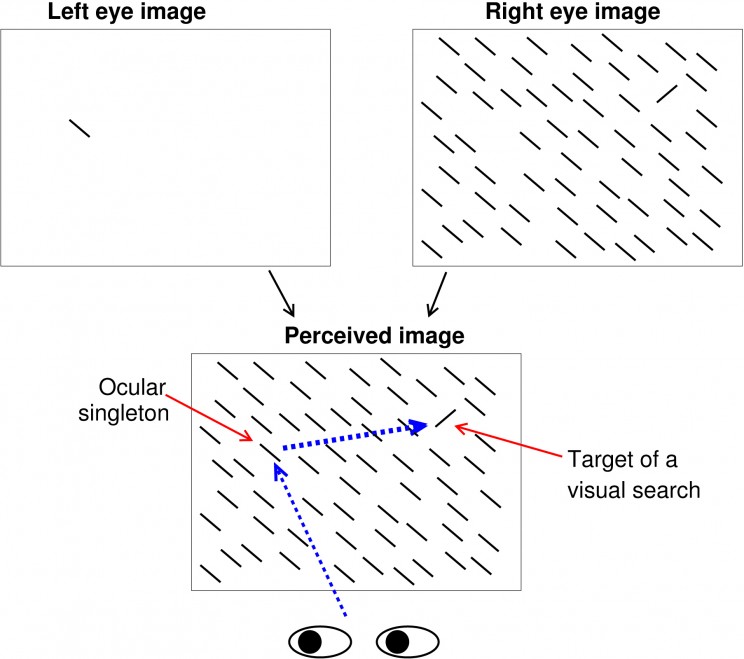

Another counter-intuitive finding, discovered only six years ago, is that our attention or gaze can be attracted by something we are blind to. In our experience, only objects that appear highly distinctive from their surroundings attract our gaze automatically. For example, a lone-red flower in a field of green leaves does so, except if we are colour-blind. Our impression that gaze capture occurs only to highly distinctive features turns out to be wrong. In the following figure, a viewer perceives an image which is a superposition of two images, one shown to each of the two eyes using the equivalent of spectacles for watching 3D movies.

Image credit: Fig 5.9 from Li Zhaoping,

Understanding Vision: Theory Models, and Data

To the viewer, it is as if the perceived image (containing only the bars but not the arrows) is shown simultaneously to both eyes. The uniquely tilted bar appears most distinctive from the background. In contrast, the ocular singleton appears identical to all the other background bars, i.e. we are blind to its distinctiveness. Nevertheless, the ocular singleton often attracts attention more strongly than the orientation singleton (so that the first gaze shift is more frequently directed to the ocular rather than the orientation singleton) even when the viewer is told to find the latter as soon as possible and ignore all distractions. This is as if this ocular singleton is uniquely coloured and distracting like the lone-red flower in a green field, except that we are “colour-blind” to it. Many vision scientists find this hard to believe without experiencing it themselves.

Are these counter-intuitive visual phenomena too alien to our “smart”, intuitive, and conscious brain to comprehend? In studying vision, are we like Earthlings trying to comprehend Martians? Landing on Mars rather than glimpsing it from afar can help the Earthlings. However, are the conscious parts of our brain too “smart” and too partial to “dumb” down suitably to the less conscious parts of our brain? Are we ill-equipped to understand vision because we are such “smart” visual animals possessing too many conscious pre-conceptions about vision? (At least we will be impartial in studying, say, electric sensing in electric fish.) Being aware of our difficulties is the first step to overcoming them – then we can truly be smart rather than smarting at our incompetence.

Headline image credit: Beautiful woman eye with long eyelashes. © RyanKing999 via iStockphoto.

The post Are we too “smart” to understand how we see? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Charley,

on 7/17/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Memory,

rubin,

cash,

elderly,

dementia,

Johnny Cash,

Social Work,

cognitive psychology,

Frailty,

*Featured,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

Psychology & Neuroscience,

Rick Rubin,

Cretien van Campen,

Mark Romanek,

Books,

creativity,

Add a tag

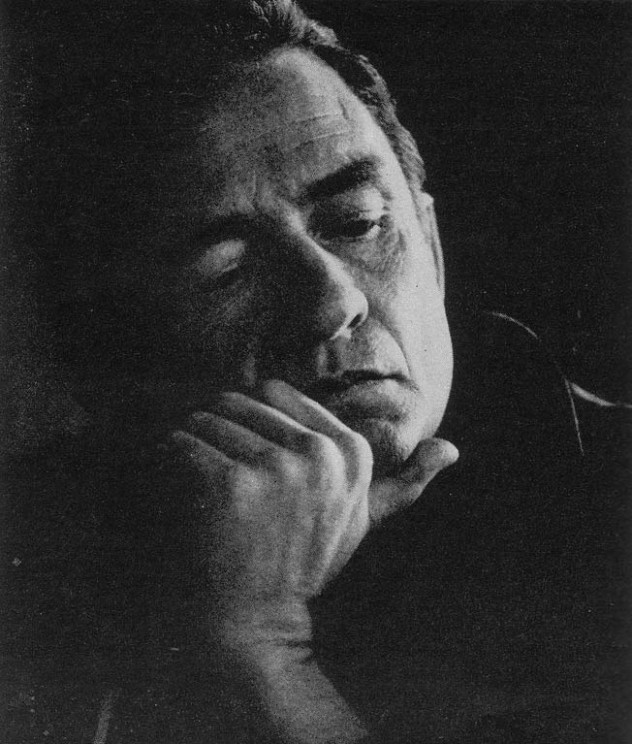

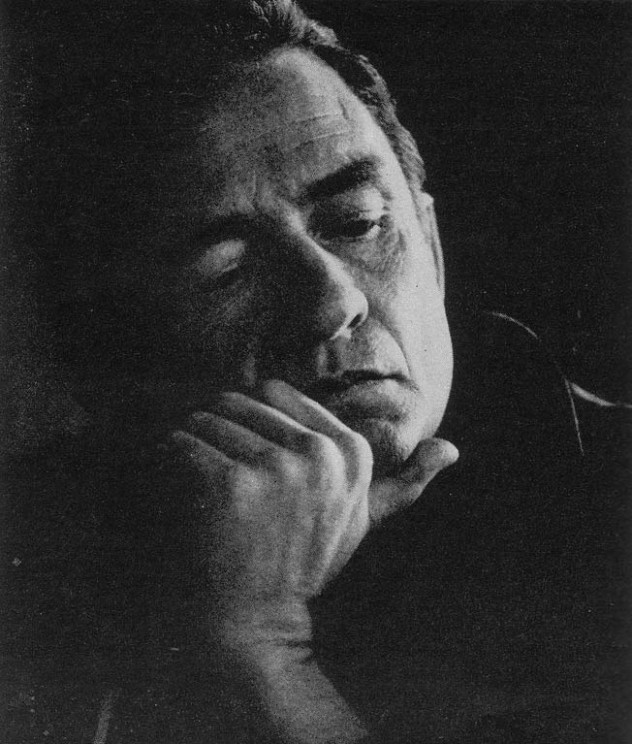

By Cretien van Campen

Frail older people are more oftentimes considered a burden for society, than not. They are perceived to require intensive care that can be expensive while producing nothing contributory to society. The collective image is that frail older people are ‘useless’. In my opinion, we do not endeavor to ‘use’ them or know how to release productivity in them.

Around the age of 70, the extremely frail wheelchair bound musician Johnny Cash made the music video ‘Hurt’ with the help of film director Mark Romanek and producer Rick Rubin. The video was a tremendous success, receiving abundant critical acclaim and becoming a favorite with many for all time. The song was taken from a series of albums, the ‘American Recordings’, Cash created in his frailest period, selling millions of copies. The albums have been regarded as outstanding contributions to American culture and many people have found strength, joy and solace in his recordings.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Cash was no exception. He was not the only frail older person who flourished in his last years. The painter Henri Matisse, the music conductor Herbert von Karajan, and others reached creative summits in the last seasons of their lives. Also non-artists like sawmill worker Lester Potts became a creative painter in his later years when he was suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. In other types of dementia, such as frontotemporal dementia, creativity can be released as well.

The case of Cash also is an example of what is needed to release creative productivity in a frail older person — and what has to be avoided. In his last years Cash suffered from several complex diseases and physical limitations, a long and sad process which biographer Robert Hilburn has described with compassion and in detail. Cash was successively diagnosed among others with Parkinson’s disease, Shy-Drager syndrome, and double pneumonia. These contributed to hospital admissions several times a year and receiving prescriptions in quantities that greatly impacted the long time Dexedrine (speed) addict. (Cash had been addicted during his career as a touring artist.)

By the end of the twentieth century Cash was in forlorn condition, exhausting himself in a mixture of drugs and over-extended tours. Of deeper emotional consequence, his records did not sell the numbers they once had. His musical career was considered by many to be over by the time he was approached by producer Rick Rubin. In retrospect Rubin gave Cash two ingredients that supported his creative productivity: mental reminiscences and physical exercises.

In elongated sessions at home Rubin and Cash played old and new music, evoking reminiscences with musical roots and connecting them with the music of younger generations, which created new flourish and renewed hunger for music in Cash. He transformed from an older musician playing golden oldies into an interpreter of contemporary songs with vision, re-honing his craft. Mentally, he returned from living in the past to living in the present and creating new interpretations, which revived a sense of direction to his life. He connected to younger generations and inspired them with his interpretations as he mutually was inspired by their music.

Not only in the mental and spiritual domains did he regain strength, but also in the physical domain. Rubin engaged a befriended physiotherapist. Physical exercises got Cash out of his wheelchair and walking independently again, while simultaneously bringing back feeling in his fingers to play the guitar with agility. By exercising his body, energy returned and he was able to sustain longer recording sessions, his most valued passion.

Rubin is an artist, not a doctor. He did not cure Cash. Instead he gave a man whose health was rapidly declining renewed opportunities and stimuli to thrive and find meaning in his life. Cash often said that all he wanted was to make music. The music gave him the will to survive, and to fight the diseases.

Although the medical records of Cash are confidential, reports from his family share indications that he was overmedicated. According to his son, his father would have lived longer and produced more songs and recordings if the medication had been decreased – something his physiotherapist pleaded for several times after another hospital admission.

Returning home after this hospital stay, every inch of his body appeared unduly medicated. As well meaning of his professional caregivers were in prescribing such pill-induced treatments, he actually lived in a medical cage, and his brilliant mind suffered. Fortunately some of his family members and friends understood he needed physical, mental, and spiritual space to flourish. They helped in opening that cage with recovered mental and physical strength and he eloquently delivered to us some of the most heart-provoking songs in the history of music.

Cretien van Campen is a Dutch author, scientific researcher and lecturer in social science and fine arts. He is the founder of Synesthetics Netherlands and is affiliated with the Netherlands Institute for Social Research and Windesheim University of Applied Sciences. He is best known for his work on synesthesia in art, including historical reviews of how artists have used synesthetic perceptions to produce art, and studies of perceived quality of life, in particular of how older people with health problems perceive their living conditions in the context of health and social care services. He is the author of The Proust Effect: The Senses as Doorways to Lost Memories.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Johnny Cash 1969, Photograph by Joe Baldwin. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Frailty and creativity appeared first on OUPblog.

By: KatherineS,

on 4/3/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

beach,

Memory,

senses,

dementia,

Nursing Homes,

cognitive psychology,

synesthesia,

*Featured,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

Psychology & Neuroscience,

care homes,

Cretien van Campen,

Sense Memories,

Snoezelen,

multisensory,

multisensory,

vreugdehof,

campen,

‘beach,

Add a tag

By Cretien van Campen

Would you take a person with dementia to the beach?

This might not really be an idea you would think of. There are several possible constraints: difficulty with travel, for example, being one. And what if, having succeeded in getting the dementia sufferer there and back, the next day you asked if they enjoyed their day out and he or she just stared at you with a confused gaze as if to ask, ‘what are you talking about?’

If you think it makes little sense to take persons with dementia to the beach, it will surprise you that a nursing home in Amsterdam has built a Beach room. In this room, residents can enjoy the feeling of sitting in the sun with their bare feet in the sand. The room is designed to improve the well-being of these residents. The garden room at the centre of the home has recently been converted into a true ‘beach room’, complete with sand and a ‘sun’ which can be adjusted in intensity and heat output. A summer breeze blows occasionally and the sounds of waves and seagulls can be heard. The décor on the walls is several metres high, giving those in the room the impression that they are looking out over the sea. There are five or six chairs in the room where the older residents can sit. There are also areas of wooden decking on which wheelchairs can be parked. The designers have even managed to replicate the impression of sea air.

Multisensory ‘Beach room’ in the Vreugdehof care centre, Amsterdam.

Visits to the beach room appear to have calming and inspiring effects on residents of the nursing home. One male resident used to go to the beach often in the past and now, after initially protesting when his daughter collected him from his bedroom, feels calm and content in the beach room. His dementia hinders us from asking him whether he remembers anything from the past, but there does appear to be a moment of recognition of a familiar setting when he is in there.

Evidence is building through studies into the sensorial aspects of memorizing and reminiscing by frail older persons in nursing and residential homes. Several experimental studies have noted the positive effects of sense memories on the subjective well-being of frail older persons. For instance, one study showed that participants of a life review course including sensory materials had significantly fewer depressive complaints and felt more in control of their lives than the control group who had watched a film.

The Beach Room is an example of a multisensory room that emanates from a specific sensorial approach to dementia. The ‘Snoezelen’ approach was initiated in the Netherlands in the late 1970s. The word ‘Snoezelen’ is a combination of two Dutch words: ‘doezelen’ (to doze) and ‘snuffelen’ (to sniff ). Snoezelen takes place in a specially equipped room where the nature, quantity, arrangement, and intensity of stimulation by touch, smells, sounds and light are controlled. The aim of these multisensory interventions is to find a balance between relaxation and activity in a safe environment. Snoezelen has become very popular in nursing homes: around 75% of homes in the Netherlands, for example, have a room set aside for snoezelen activities.

On request by health care institutions, artists have taken up the challenge to design multisensory rooms or redesign the multisensory space of wards (e.g. distinguished by smells) and procedures (cooking and eating together instead of individual microwave dinners). Besides a few scientific evaluations, most evidence is actually acquired from collaborations of artists and health professionals at the moment. The senses are often a better way of communicating with people affected by deep dementia. Like the way that novelist Marcel Proust opened the joys of his childhood memories with the flavour of a Madeleine cake dipped in linden-blossom tea, these artistic health projects open windows to a variety of ways of using sensorial materials to reach unreachable people.

So, would you take a person with dementia to the beach? Yes, take them to the beach! It can evoke Proust effects and enhance their joy and well-being. Although, we still do not know what the Proust effect does inside the minds of people with dementia, we can oftentimes observe the result as an enhanced state of calmness with perhaps a little smile on their face. People with dementia who have lost so much of their quality of life can still experience moments of joy and serenity through their sense memories.

Cretien van Campen is a Dutch author, scientific researcher and lecturer in social science and fine arts. He is the founder of Synesthetics Netherlands and is affiliated with the Netherlands Institute for Social Research and Windesheim University of Applied Sciences. He is best known for his work on synesthesia in art, including historical reviews of how artists have used synesthetic perceptions to produce art, and studies of perceived quality of life, in particular of how older people with health problems perceive their living conditions in the context of health and social care services. He is the author of The Proust Effect: The Senses as Doorways to Lost Memories.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: Multisensory ‘Beach room’ in the Vreugdehof care centre, Amsterdam. Photo: Cor Mantel, with permission from Vreugdehof.

The post Dementia on the beach appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Nicola,

on 1/23/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Psychology,

evolution,

Anthropology,

homo sapiens,

Humanities,

cognitive psychology,

*Featured,

Science & Medicine,

frederick l coolidge,

homo heidelbergensis,

neanderthal,

linguistics,

homo,

wynn,

language history,

how to think like a neandertal,

neandertal speech,

paleoanthropology,

thomas wynn,

neandertal,

neandertal,

neandertals,

neandertals,

heidelbergensis,

sapiens,

Add a tag

By Thomas Wynn and Frederick L. Coolidge

Neandertal communication must have been different from modern language. To repeat a point made often in this book, Neandertals were not a stage of evolution that preceded modern humans. They were a distinct population that had a separate evolutionary history for several hundred thousand years, during which time they evolved a number of derived characteristics not shared with Homo sapiens sapiens. At the same time, a continent away, our ancestors were evolving as well. Undoubtedly both Neandertals and Homo sapiens sapiens continued to share many characteristics that each retained from their common ancestor, including characteristics of communication. To put it another way, the only features that we can confidently assign to both Neandertals and Homo sapiens sapiens are features inherited from Homo heidelbergensis. If Homo heidelbergensis communicated via modern style words and modern syntax, then we can safely attribute these to Neandertals as well. Most scholars find this highly unlikely, largely because Homo heidelbergensis brains were slightly smaller than ours and smaller than Neandertals’, but also because the archaeological record of Homo heidelbergensis is much less ‘modern’ than either ours or Neandertals’. Thus, we must conclude that Neandertal communication had evolved along its own path, and that this path may have been quite different from the one followed by our ancestors. The result must have been a difference far greater than the difference between Chinese and English, or indeed between any pair of human languages. Specifying just how Neandertal communication differed from ours may be impossible, at least at our current level of understanding. But we can attempt to set out general features of Neandertal communication based on what we know from the comparative, fossil, and archaeological records.

As we have tried to show in previous chapters, the paleoanthropological record of Neandertals suggests that they relied heavily on two styles of thinking – expert cognition and embodied social cognition. These, at least, are the cognitive styles that best encompass what we know of Neandertal daily life. And they do carry implications for communication. Neandertals were expert stone knappers, relied on detailed knowledge of landscape, and a large body of hunting tactics. It is possible that all of this knowledge existed as alinguistic motor procedures learned through observation, failure, and repetition. We just think it unlikely. If an experienced knapper could focus the attention of a novice using words it would be easier to learn Levallois. Even more useful would be labels for features of the landscape, and perhaps even routes, enabling Neandertal hunters to refer to any location in their territories. Such labels would almost have been required if widely dispersed foraging groups needed to congregate at certain places (e.g., La Cotte). And most critical of all, in a natural selection sense, would be an ability to indicate a hunting tactic prior to execution. These labels must have been words of some kind. We suspect that Neandertal words were always embedded in a rich social and environmental context that included gesturing (e.g., pointing) and emotionally laden tones of voice, much as most human vocal communication is similarly embedded, a feature of communication probably inherited from Homo heidelbergensis.

At the risk of crawling even further out on a limb than the two of us usually go, we make the following suggestions about Neandertal communication:

1) Neandertals had speech. Their expanded Broca’s area in the brain, and their possession of a human FOXP2 gene both suggest this. Neandertal speech was probably based on a large (perhaps huge) vocabulary – words for places, routes, techniques, individuals, and emotions. We have shown that Neandertal expertise was large