The first collected edition of Shakespeare's plays printed in 1623 - known as the First Folio - has a rich history. It is estimated that around 700 or 750 copies were printed, and today we know the whereabouts of over 230. They exist in some form or another, often incomplete or a combination of different copies melded together, in libraries and personal collections all over the world.

The post Copies of Shakespeare’s First Folio around the world [map] appeared first on OUPblog.

Two hundred years ago last Friday the owner of the London Times, John Walter II, is said to have surprised a room full of printers who were preparing hand presses for the production of that day’s paper. He showed them an already completed copy of the paper and announced, “The Times is already printed – by steam.” The paper had been printed the night before on a steam-driven press, and without their labor. Walter anticipated and tried to mediate the shock and unrest with which this news was met by the now-idled printers. It was one of many scenes of change and conflict in early industrialization where the hand was replaced by the machine. Similar scenes of hand labor versus steam entered into cultural memory from Romantic poetry about framebreaking Luddites to John Henry’s hand-hammering race against the steam drill.

There were many reasons to celebrate the advent of the steam press in 1814, as well as reasons to worry about it. Steam printing brought the cost of printing down, increased the number of possible impressions per day by four times, and, in a way, we might say that it helped “democratize” access to information. That day, the Times proclaimed that the introduction of steam was the “greatest improvement” to printing since its very invention. Further down that page, which itself was “taken off last night by a mechanical apparatus,” we read why the hand press printers might have been concerned: “after the letters are placed by the compositors… little more remains for man to do, than to attend upon, and watch this unconscious agent in its operations.”

Moments of technological change do indeed put people out of work. My father, who worked at the Buffalo News for nearly his entire career, often told me about layoffs or fears of layoffs coming with the development of new computerized presses, print processes, and dwindling markets for print. But the narrative of the hand versus the machine, or of the movement from the hand to the machine, obscures a truth about labor, especially information labor. Forms of human labor are replaced (and often quantifiably reduced), but they are also rearranged, creating new forms of work and social relations around them. We would do well to avoid the assumption that no one worked the steam press once hand presses went mostly idle. As information, production, and circulation becomes more technologically abstracted from the hands of workers, there is an increased tendency to assume that no labor is behind it.

Two hundred years after the morning when the promise of faster, cheaper, and more accessible print created uncertainty among the workers who produced it, I am writing to you using an Apple Computer made by workers in Shenzhen, China with metals mined all over the global South. The software I am using to accomplish this task was likely written and maintained by programmers in India managed by consultants in the United States. You are likely reading this on a similar device. Information has been transmitted between us via networks of wires, servers, cable lines, and wireless routers, all with their own histories of people who labor. If you clicked over here from Facebook, a worker in a cubicle in Manilla may have glanced over this link among thousands of others while trying to filter out content that violates the social network’s terms of service. Technical laborers, paid highly or almost nothing at all, and working under a range of conditions, are silently mediating this moment of exchange between us. Though they may no longer be hand-pressed, the surfaces on which we read and write are never too distant from the hands of information workers.

Like research in book history and print culture studies, the common appearance of a worker’s hand in Google Books reminds us that, despite radical changes in technology over centuries, texts are material objects and are negotiated by numerous people for diverse purposes, only some of which we would call “reading” proper. The hand pulling the lever of a hand press and the hand turning pages in scanner may be representative of two poles on a two-century timeline, but, for me, they suggest many more continuities between early print and contemporary digital cultures than ruptures. John Walter II’s proclamation on 28 November 1814 was not a turn away from a Romantic past of artisanal labor toward a bleak and mechanized future. Rather, it was an early moment in an ongoing struggle to create and circulate words and images to ever more people while also sustaining the lives of those who produce them. Instead of assuming, two hundred years on, that we have been on a trajectory away from the hand, we must continue looking for and asking about the conditions of the hand in the machine.

Headline image credit: Hand of Google, by Unknown CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The hand and the machine appeared first on OUPblog.

We’re continuing our discussion of what is a book today with some historical perspective. The excerpt below by Andrew Robinson from The Book: A Global History gives some interesting insight into how the art of writing began.

Without writing, there would be no recording, no history, and of course no books. The creation of writing permitted the command of a ruler and his seal to extend far beyond his sight and voice, and even to survive his death. If the Rosetta Stone did not exist, for example, the world would be virtually unaware of the nondescript Egyptian king Ptolemy V Epiphanes, whose priests promulgated his decree upon the stone in three scripts: hieroglyphic, demotic, and (Greek) alphabetic.

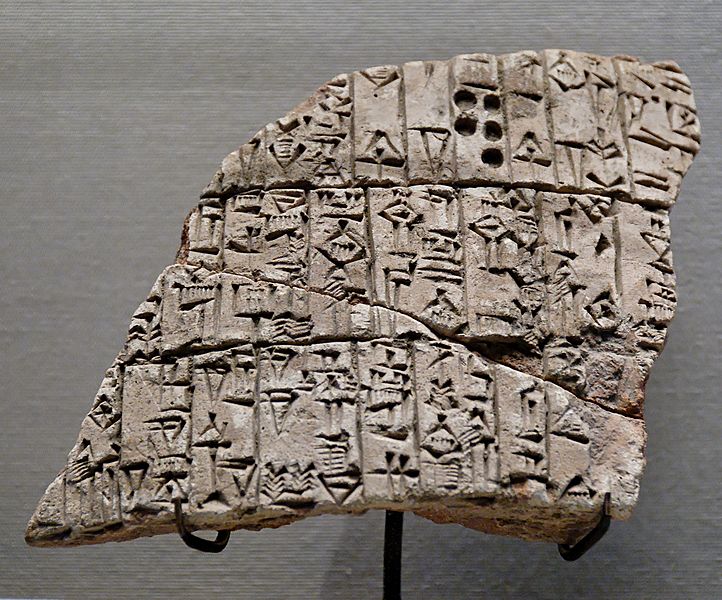

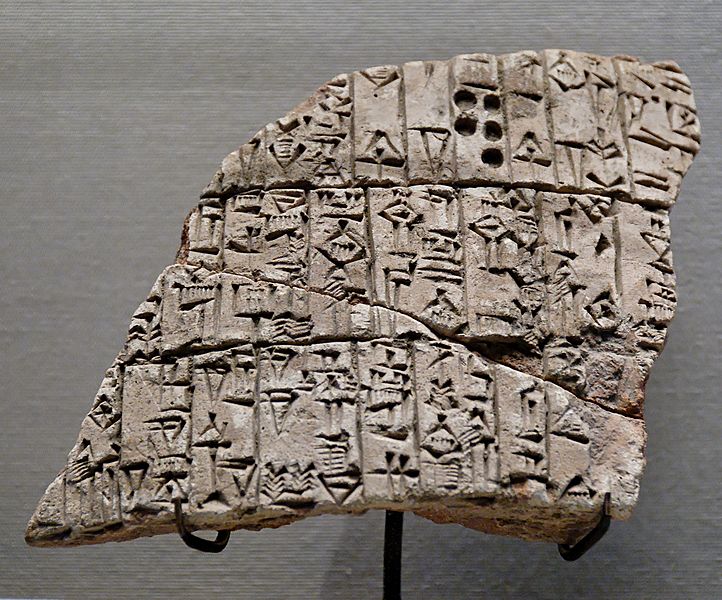

How did writing begin? The favoured explanation, until the Enlightenment in the 18th century, was divine origin. Today, many—probably most—scholars accept that the earliest writing evolved from accountancy, though it is puzzling that such accounts are little in evidence in the surviving writing of ancient Egypt, India, China, and Central America (which does not preclude commercial record-keeping on perishable materials such as bamboo in these early civilizations). In other words, some time in the late 4th millennium bc, in the cities of Sumer in Mesopotamia, the ‘cradle of civilization’, the complexity of trade and administration reached a point where it outstripped the power of memory among the governing elite. To record transactions in an indisputable, permanent form became essential.

Fragment of an inscripted clay cone of Urukagina (or Uruinimgina), lugal (prince) of Lagash. circa 2350 BC. terracotta. Musée du Louvre. Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Some scholars believe that a conscious search for a solution to this problem by an unknown Sumerian individual in the city of Uruk (biblical Erech), c .3300 bc, produced writing. Others posit that writing was the work of a group, presumably of clever administrators and merchants. Still others think it was not an invention at all, but an accidental discovery. Many regard it as the result of evolution over a long period, rather than a flash of inspiration. One particularly well-aired theory holds that writing grew out of a long-standing counting system of clay ‘tokens’. Such ‘tokens’—varying from simple, plain discs to more complex, incised shapes whose exact purpose is unknown—have been found in many Middle Eastern archaeological sites, and have been dated from 8000 to 1500 bc. The substitution of two-dimensional symbols in clay for these three dimensional tokens was a first step towards writing, according to this theory. One major difficulty is that the ‘tokens’ continued to exist long after the emergence of Sumerian cuneiform writing; another is that a two-dimensional symbol on a clay tablet might be thought to be a less, not a more, advanced concept than a three-dimensional clay ‘token’. It seems more likely that ‘tokens’ accompanied the emergence of writing, rather than giving rise to writing.

Apart from the ‘tokens’, numerous examples exist of what might be termed ‘proto-writing’. They include the Ice Age symbols found in caves in southern France, which are probably 20,000 years old. A cave at Pech Merle, in the Lot, contains a lively Ice Age graffiti to showing a stenciled hand and a pattern of red dots. This may simply mean: ‘I was here, with my animals’—or perhaps the symbolism is deeper. Other prehistoric images show animals such as horses, a stag’s head, and bison, overlaid with signs; and notched bones have been found that apparently served as lunar calendars.

‘Proto-writing’ is not writing in the full sense of the word. A scholar of writing, the Sinologist John DeFrancis , has defined ‘full’ writing as a ‘system of graphic symbols that can be used to convey any and all thought’—a concise and influential definition. According to this, ‘proto-writing’ would include, in addition to Ice Age cave symbols and Middle Eastern clay ‘tokens’, the Pictish symbol stones and tallies such as the fascinating knotted Inca quipus, but also contemporary sign systems such as international transportation symbols, highway code signs, computer icons, and mathematical and musical notation. None of these ancient or modern systems is capable of expressing ‘any and all thought’, but each is good at specialized communication (DeFrancis, Visible Speech, 4).

Andrew Robinson is the author of some 25 books in the arts and sciences including Writing and Script: A Very Short Introduction and Cracking the Egyptian Code: The Revolutionary Life of Jean-François Champollion. He is a contributor to The Book: A Global History, edited by Michael F. Suarez, S.J. and H. R. Woudhuysen.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only humanities articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post How did writing begin? appeared first on OUPblog.

From ancient times to the creation of eBooks, books have a long and vast history that spans the globe. Although a book may only seem like a collection of pages with words, they are also an art form that have survived for centuries. In honor of National Library Week, we couldn’t think of a more fitting book to share than The Book: A Global History. The slideshow below highlights the fascinating evolution of the book.

-

Origin of the alphabet

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/195-Origin-of-the-Alphabet.jpg

The proto-Sinaitic theory of the origin of the alphabet. Line drawing by Chartwell Illustrators.

-

Illustrations of runic stones

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/148-Runic-Stones.jpg

Illustrations of runic stones from the Danish scholar Carl Rafn’s ‘Runic Inscriptions in which the Western Countries are Alluded to’, in Mémoires de la Société Royale des Antiquaires du Nord, 1848–9 (Copenhagen, 1852); the variety of languages is notable. Private collection.

-

Composing frame

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/89-composing-frame.jpg

A composing frame with two sets of cases of type: the upper case lies at a steeper angle than the lower case. By permission of Oxford University Press.

-

Cuneiform signs

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/192-cuneiform.jpg

Some cuneiform (wedge-shaped) signs, showing the pictographic form (c .3000 BC ), an early cuneiform representation (c. 2400 BC ), and the late Assyrian form ( c .650 BC ), now turned through 90 degrees, with the meaning. Line drawing by Chartwell Illustrators.

-

Modern casebound Book

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/181-Modern-Casebound-Book.jpg

Diagram of the structural features of a modern casebound book ready for casing in (adapted from Gaskell, NI ). Line drawing by Chartwell Illustrators.

-

East Asian book forms

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/158-East-Asian-books.jpg

Traditional East Asian book forms. A (top): scroll binding: 18 th -century printed Buddhist sutra (Japan). B (2 nd from top): pleated binding, 17 th -century printed Buddhist sutra (Japan). C (3 rd from top left): butterfly binding: 16th -century Buddhist MS (Japan). D (3 rd from top right): butterf19ly binding: contemporary printed book bound in traditional style (China). E (bottom left): wrapped back binding with original printed title label: 17th-century printed book (China). F (bottom centre): thread binding: 18th-century printed book (China). G (bottom right): protective folding case, MS title label: early 20th century (China). © J. S. Edgren

-

Medieval European bookbinding

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/180-Europen-Bookbinding.jpg

The basic structural features of a European bookbinding in the medieval and hand press periods. Line drawing by Chartwell Illustrators.

-

Pica italic matrices

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/88-John-Fells.jpg

A box of John Fell’s pica italic matrices, with some steel punches for larger capitals beneath them. By permission of Oxford University Press

In celebration of National Library Week we’re giving away 10 copies of The Book: A Global History, edited by Michael F. Suarez, S.J. and H.R. Woudhuysen. Learn more and enter for a chance to win.

Michael F. Suarez, S.J. and H. R. Woudhuysen are the authors of The Book: A Global History. Michael F. Suarez S.J. is Professor and Director of the Rare Book School at the University of Virginia. H. R. Woudhuysen is Rector of Lincoln College, Oxford.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only humanities articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A bookish slideshow appeared first on OUPblog.