By Philip Durkin

The obvious answer to ‘when is a book a tree?’ is ‘before it’s been made into a book’ – it doesn’t take a scientist to know that (most) paper comes from trees – but things get more complex when we turn our attention to etymology.

The word book itself has changed very little over the centuries. In Old English it had the form bōc, and it is of Germanic origin, related to for example Dutch boek, German Buch, or Gothic bōka. The meaning has remained fairly steady too: in Old English a bōc was a volume consisting of a series of written and/or illustrated pages bound together for ease of reading, or the text that was written in such a volume, or a blank notebook, or sometimes another sort of written document, such as a charter.

The argument for…

The pages of books in Anglo-Saxon times were made out of parchment (i.e. animal skin), not paper. But nonetheless a long-standing and still widely accepted etymology assumes that the Germanic base of book is related ultimately to the name of the beech tree. Explanations of the semantic connection have varied considerably. At one point, scholars generally focused on the practice of scratching runes (the early Germanic writing system) onto strips of wood, but more recent accounts have placed emphasis instead on the use of wooden writing tablets.

Words in other languages have followed this semantic development from ‘material for writing on’ to ‘writing, book’. One example is classical Latin liber meaning ‘book’ (which is the root of library). This is believed to have originally been a use of liber meaning ‘bark’, the bark of trees having, according to Roman tradition, been used in early times as a writing material. Compare also Sanskrit bhūrjá- (as masculine noun) ‘birch tree’, and (as feminine noun) ‘birch bark used for writing’.

The argument against…

This explanation has troubled some scholars. There are two main reasons for this. Firstly, the words for ‘book’ and ‘beech’ in the earliest recorded stages of various Germanic languages belong to different stem classes (which determine how they form their endings for grammatical case and number), and the word for ‘book’ shows a stem class that is often assumed to be more archaic than that shown by the word for ‘beech’.

Secondly, in Gothic (the language of the ancient Goths, preserved in important early manuscripts) bōka in the singular (usually) means ‘letter (of the alphabet)’. In the plural, Gothic bōkōs does also mean ‘(legal) document, book’, but some have argued that this reflects a later development, modelled on ancient Greek γράμμα (gramma) ‘letter, written mark’, also in the plural γράμματα (grammata) ‘letters, literature’ (this word ultimately gives modern English grammar), and also on classical Latin littera ‘letter of the alphabet, short piece of writing’, also in the plural litterae ‘document, text, book’ (this word ultimately gives modern English literature).

In light of these factors, some have suggested that book and its Germanic relatives may show a different origin, from the same Indo-European base as Sanskrit bhāga- ‘portion, lot, possession’ and Avestan baga ‘portion, lot, luck’. The hypothesis is that a word of this origin came to be used in Germanic for a piece of wood with runes (or a single rune) inscribed on it, used to cast lots (a practice described by the ancient historian Tacitus), then for the runic characters themselves, and hence for Greek and Latin letters, and eventually for texts and books containing these.

However, many scholars remain convinced that book and beech are ultimately related, and argue that the forms and meanings shown in the earliest written documents in the various Germanic languages already reflect the results of a long process of development in word form and meaning, which has obscured the original relationship between the word book and the name of the tree. For some more detail on this, and for references to some of the main discussions of the etymology of book, see the etymology section of the entry for book in OED Online.

This article first appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Philip Durkin is Deputy Chief Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, and the author of Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English.

Language matters. At Oxford Dictionaries, we are committed to bringing you the benefit of our language expertise to help you connect with your world.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post When is a book a tree? appeared first on OUPblog.

As the Amazon-Hachette debate has escalated this week, taking a notably funny turn on the Colbert Report, we’d like to share some funnier reflections on books and the purposes they serve. Here are a few selections from the Oxford Dictionary of Humorous Quotations, Fifth Edition.

“Book–what they make a movie out of for television”

–Leonard Louis Levinson 1904-74: Laurence J. Peter (ed) Quotations for our Time (1977)

“If you don’t find it in the Index, look very carefully through the entire catalogue.”

–Anonymous: in Consumer’s Guide, Sears, Roebuck and Co. (1897); Donald E. Knuth Sorting and Searching (1973)

“Books and harlots have their quarrels in public.”

–Walter Benjamin 1892-1940 German philosopher and critic: One Way Street (1928)

“My desire is … that mine adversary had written a book.”

–Bible: Job

“The covers of this book are too far apart.”

–Ambrose Bierce 1842-c.1914 American writer; C.H. Grattam Bitter Bierce (1929)

“When the [Supreme] Court moved to Washington in 1800, it was provided with no books, which probably explains the high quality of early opinions.”

–Robert H. Jackson 1892-1954 American lawyer: The Supreme Court in the American System of Government (1955)

“One man is as good as another until he has written a book.”

–Benjamin Jowett 1817-93 English classicist: Evelyn Abbott and Lewis Campbell (eds.) Life and Letters of Benjamin Jowett (1897)

“This is not a novel to be tossed aside lightly. It should be thrown with great force.”

–Dorothy Parker 1893-1967 American critic and humorist: R.E. Drennan Wit’s End (1973)

“A thick, old-fashioned heavy book with a clasp is the finest thing in the world to throw at a noisy cat.”

–Mark Twain 1835-1910 American writer: Alex Ayres The Wit and Wisdom of Mark Twain (1987)

“An index is a great leveller.”

–George Bernard Shaw 1856-1950 Irish dramatist: G.N. Knight Indexing (1979); attributed, perhaps apocryphal

“Digressions, incontestably, are the sunshine;–they are the life, the soul of reading;–take them out of this book for instance,–you might as well take the book along with them.”

–Laurence Sterne 1713-68 English novelist: Tristram Shandy (1759-67)

“In every first novel the hero is the author as Christ or Faust.”

–Oscar Wilde 1854-1900 Irish dramatist and poet: attributed

Writer, broadcaster, and wit Gyles Brandreth has completely revised Ned Sherrin’s classic collection of wisecracks, one-liners, and anecdotes. With over 1,000 new quotations throughout the media, it’s easy to find hilarious quotes on subjects ranging from Argument to Diets, from Computers to the Weather. Add sparkle to your speeches and presentations, or just enjoy a good laugh in the company of Oscar Wilde, Mark Twain, Joan Rivers, Kathy Lette, Frankie Boyle, and friends. Gyles Brandreth is a high profile comedian, writer, reporter on The One Show and keen participant in radio and TV quiz shows.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Bookcase. Public domain via Pixababy.

The post What is a book? (humour edition) appeared first on OUPblog.

We’re continuing our examination of what a book is this week, following the cultural debate the Amazon-Hachette dispute has set off, with something a little closer to our hearts. We’ve compiled a brief list of books that changed the lives of Oxford University Press staff. Please share your books in the comments below.

Jonathan Kroberger, Publicist:

Jonathan Kroberger, Publicist:

A Wrinkle In Time by Madeleine L’Engle

A Wrinkle In Time was the first book to change my life, the one that set me up for all the others that continue to do so. My parents read to me for as long as I can remember but this was the first book I found independently in the school library. It sounds cliché, but reading it felt absolutely like stumbling onto a place that was just my own. That feeling of reading as independence continues to be one of the main reasons I value reading as much as I do.

Annabel Daly, Senior Marketing Manager:

Gift from the Sea by Anne Morrow Lindbergh

This paragraph, while not necessarily my favourite, reminds me of why I love it and why it changed me:

And then, some morning in the second week, the mind wakes, comes to life again. Not in a city sense – no – but beach-wise. It begins to drift, to play, to turn over in gentle careless rolls like those lazy waves on the beach. One never knows what chance treasures these easy unconscious rollers might toss up, on the smooth white sand of the conscious mind; what perfectly rounded stone, what rare shell from the ocean floor. Perhaps a channelled whelk, a moon shell, or even an argonaut.

Ryan Curry, Assistant Marketing Manager:

An Actor Prepares by Constantin Stanislavski

When I was 14 years old, merely a freshman in high school, I had the opportunity to portray Jem Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird at the Barter Theater–the state theater of Virginia, located in the small town of Abingdon, Virginia where I grew up. As a child actor, I was assigned an adult actor who would serve as a mentor to me throughout the entirety of the run of the show: from costume fittings to the final bow. This mentor would be a leader, an older “brother” or “sister,” essentially someone to look up to. The week before we opened the show, my mentor (who was portraying Boo Radley), gave me the book An Actor Prepares by Constantin Stanislavski–a critical read to every actor’s beginning. I flew through the book. Every page. While I don’t act regularly anymore, I continue to reference this book and always prominently place it up front on my book shelf. Inside the front cover reads a note from my mentor that I will always cherish. It brings me to a place where I learned to be vulnerable and grow not only as an actor, but as an individual.

Trans Bodies, Trans Selves, edited by Laura Erickson-Schroth

Trans Bodies, Trans Selves, edited by Laura Erickson-Schroth

A revolutionary book was placed into my lap as one of my first projects here at Oxford University Press. A resource book to the transsexual community: Trans Bodies, Trans Selves edited by Laura Erickson-Schroth. As an out, gay male in his 20s, this book continues to considerably have a positive effect on me–the energy behind the scenes is palpable. The cast of characters who built the book, the amazing editor who pieced each intricate story together, and the wonderful teams who work to get the book out there: this title goes far beyond work, standing out to me personally. I understand this community and completely respect the impact it will have in the world. Having had the opportunity to attend the book’s launch party, I will always remember the tears of joy from contributors, guests, and friends. It reminded me that I am not alone in this endeavor. I am very excited to be a part of this book and look forward to see it take off once publishing.

Yasmin Spark, Digital Assistant:

The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison

The book that changed my life was The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison. The novel uses the protagonist to confront the complex internal mechanisms that young black women have to process as they deal with growing up in a society still dominated by state and institutional racism and the way this impacts their self-esteem. Not only was it fantastically written but it was the first empowering black female character I had ever come across. My mum passed it to me and I fully intend to pass it down to my daughters!

Barney Cox, Marketing Executive:

Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell

Describing David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas is a near-impossible task. The book is a series of stories set in six different periods — including Colonial Australia, a dystopian clone-filled Seoul, and a post-apocalyptic future of tribes and cannibals — each featuring a protagonist with a comet-shaped birthmark. The time periods could not feel more different from the other, but as you read more, the novel unfurls itself, slowly giving up its secrets, and you begin to realise how the stories and the lives within them are linked together across time and space. “Souls cross ages like clouds cross skies” is the central premise — and it’s a heart-breakingly beautiful one, the idea of lovers meeting again and again in different worlds and times, of people linked to each other across hundreds and thousands of years, or of having lived past lives they’re only dimly aware of. I haven’t done it justice in this description, but it’s just the tonic for whenever I might have a bad case of the existentialist blues. In one scene, a character angrily tells another that his life will only amount to “one drop in a limitless ocean”, to which the other replies “Yet, what is any ocean but a multitude of drops?” Enough said.

Hannah Charters, Senior Marketing Executive:

His Dark Materials trilogy by Philip Pullman

I always had a love of reading as a child, but the book (or set of books) which turned that love into a passion that formed my future choices (from a university degree in English Literature to my career path in publishing) was Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy. This set of three books (Northern Lights, The Subtle Knife, and The Amber Spyglass) is based in a universe where humans have dæmons, an animal-shaped being who represents the true inner-self, polar bears are armoured and can talk, and witches roam the skies. I got lost in these books that followed two children, Lyra and Will, through parallel worlds, discovering along with them what they learnt: about themselves, their world, and the people around them. I learnt more later, as I grew older, about the religious significances and literary undertones (much of the plot is influenced by John Milton’s Paradise Lost), furthering my love of the books, their characters, and the literary world they sat in.

Andy Allen, Marketing Manager:

Andy Allen, Marketing Manager:

The Beach by Alex Garland

When I read this book, I think I was looking for something to read on a long train journey or something and this just happened to be around. I think the fact that I was at a loose end after finishing university was perfect timing, as it contributed to me deciding to then go traveling around Southeast Asia for a few months. Even though it wasn’t the best book I have ever read it probably has been the most influential. (I didn’t find any secret beaches.)

The 4-Hour Work Week by Timothy Ferriss

While I haven’t read this book, the title alone has sold it to me, and if true, would actually be a life changer! Although I guess you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover; maybe I am a sucker for a get rich quick scheme.

Caitie-Jane Cook, Marketing Executive:

Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh

Growing up in Scotland, I felt a sense of distance when told that I would be studying English Literature as a core subject. Although “Scottish play” Macbeth had a pivotal role in the higher curriculum, I was disappointed there wasn’t anything closer to home, more ‘real’. When given free rein to select texts for my final-year portfolio, I was immediately drawn towards Trainspotting. Although sometimes brutal, I found Irvine Welsh’s representation of Mark Renton and friends’ experience of heroin addiction captivating and oddly charming. Most importantly, it was written primarily in Scots. I then went on to study English Language at university, taking special interest in the relative status of the Scots language and why it’s often dismissed as “slang”. I now recognise Welsh’s writing as the source of this linguistic fascination; Trainspotting made me realise that Scots is a language worthy of its own literature.

Ibrahim Siddo, Data Controller:

L’Étrange destin de Wangrin by Amadou Hampaté Bâ

I have selected this one because it’s basically one of the first books I read (I am sure it was over 15 years ago!). It’s about the fortunes (destiny) of an interpreter during the French West African colonial period who had to live between two ‘worlds’ and take/make difficult decisions/choices…

« Wangrin était filou, certes, mais son âme n’était pas insensible. Son cœur était habité par un intense volonté de gagner de l’argent par tous les moyens afin de satisfaire une convoitise innée, mais il n’était point dépourvu de bonté, de générosité et même de grandeur. Les pauvres et tous ceux auxquels ils étaient venus en aide dans le secret en savaient quelque chose. Son comportement, cynique envers les puissants et les favorisés de la fortune, ne manquait cependant jamais d’une certaine élégance. »

Kirsty Doole, Publicity Manager:

Kirsty Doole, Publicity Manager:

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë

Reading Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë when I was 16 is an experience that has stayed with me. Being 16 and a goth, I thought I understood it in a way that no one else ever had, ever. Of course, that was nonsense, but it was still the book that ignited my interest in Victorian novels — something that I went on to study at university — and it remains a firm favourite of mine. I love the characters, the multi-generational scope, and, of course, Emily’s powerful descriptions of the Yorkshire moors. Going back to it, as I do periodically, is like meeting up with an old friend again.

Alyssa Bender, Marketing Coordinator:

The Harry Potter series

Not necessarily one book that I’d say changed my life but seven: the Harry Potter series. I can single-handedly attribute my love of reading to these books. They turned me into a voracious reader and turned me on to so many other books over the years. As I grew up and the later books started coming out, they provided a fun online community as well as endless conversations and release parties with high school friends. Now, they are a source of nostalgia and are immensely enjoyable every time I return to them. I don’t think I would be the avid reader I am today without them.

Alana Podolsky, Associate Publicist:

1984 by George Orwell

When assigned George Orwell’s 1984 in ninth grade, I probably joined my fellow classmates in groans when the tome hit our desks. That quickly changed for me. I remember 1984 as the book that transformed me from a young reader interested only in plot and character to an adult reader that values art as politics and narrative construction. Orwell of course is brilliant, but 1984 went farther in teaching me that reading can be political and that through reading, you can experience the world.

Georgia Mierswa, Marketing Coordinator:

Brokeback Mountain by Annie Proulx

Regardless of its unassuming size, or its status as a “short story,” Annie Proulx’s Brokeback Mountain moved me beyond words. The surprise of this story, for me, was not that two cowboys fell in love; rather, that Proulx successfully paints a complex thirty-year-long relationship, one based on anger, guilt, and fear of being found out, in less than 60 pages. Their love is violent and pained: when they kiss, they draw blood. A hug turns into a wrestling match in which Jack’s knee connects with Ennis’ nose. These small moments speak volumes about their internal struggle—as trapped men in a prejudice place. When I reached Ennis’s final line, a quote as gut-wrenching and unrealized as their affair (“Jack, I swear—”), I was in tears. Brokeback Mountain is more honest about love, and the anguish of forbidden relationships, than any work I’ve ever read.

Jacqueline Baker, Senior Commissioning Editor, Literature:

Jacqueline Baker, Senior Commissioning Editor, Literature:

Mara and Dann by Doris Lessing

I picked up a copy of Doris Lessing’s Mara and Dann (first published in the UK in 1999) in a scuffed paperback edition sitting on the shelves of a holiday apartment in the hot and dry region of the Var in the south of France in the summer of 2005. I had packed books that I intended to read in my suitcase, but felt like something different and was perusing the resident bookcase. Mara and Dann, brother and sister, live at the southern end of all large land mass called Ifrik. It’s an imagined place set in a post-cataclysmic era and the reader has to piece together the background to their decision to flee from their home and family in the middle of the night. They find themselves in a poor rural village and join the general fight to survive the hardships of a life threatened by drought, wild animals, and hostility from the Rock People. Reading it in the south of France in the extreme arid heat and a foreboding sense of climate change hanging over me as the helicopters circled attempting to put out forest fires must have enhanced the impact of the book – Mara and Dann have to migrate north, away from the southern lands that are turning to dust. All sorts of odd things happen to them, in extremis, and they are separated at several points in the narrative. The odd bond between brother-sister is rather like that between Maggie Tulliver and her brother in George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss, but this time life is nightmarish and civilisation a half-remembered human state the only remaining traces of which – a few surviving books – are completely mysterious and undecipherable. The world is returned to its primitive state, but we know that we’re really in the future. It’s a dark, haunting book but there is an extraordinary relationship at its core. The mood and world of the book has stayed with me ever since.

Seth Bitter, Library Sales Associate:

The Lamp from the Warlock’s Tomb by John Bellairs

The first book that I can accurately recall having a profound impact on my life would have to be The Lamp from the Warlock’s Tomb by John Bellairs. I was already an avid reader by the time I came across it, but I was mostly reading the same books that my older siblings had read, and those that were available on our bookshelves at home. The discovery of John Bellairs and his gothic mysteries was one of the first independent steps I took. It gave me a section of the library to dart towards whenever we made our weekly trip, and the ghostly cover illustrations by Edward Gorey only helped to cement their place in my mind.

Alice Northover, Social Media Marketing Manager:

Animal Farm by George Orwell

I wasn’t a great reader as a child, despite my family’s ability to exhaust the local library or our weekly classroom trips to the school library. My childhood was filled with books that people thought I ought to read, whether classics like Black Beauty or the Babysitters Club series, but I never found any of those books appealing. There were certainly a few that touched me (how could you fail to cry at the end of Where the Red Fern Grows?), yet something kept turning me away. Perhaps the weight of expectations in those books left me cold — whether as school assignments, or gifts, or suggestions from kind librarians, or the creeping, patronizing tones of children’s authors I found in so many. Other children loved those books, so clearly I was the problem. So when I was assigned Animal Farm for summer reading at 12-years-old, students were supposed to hate it, to fail to understand it, to find it too advanced (they had a terrible way of introducing summer reading). I was supposed to identify with the other assignment, an insipid — if award-winning — book about some teenager envious of her cancer-stricken sister. Animal Farm was the first book, however, that truly challenged and engaged me. It spoke about systems of power, complex and contradictory people, societies in flux, and politics, real politics; about a world outside my claustrophobic suburbia. And George Orwell did not speak down to me (I doubt he thought 12-year-olds would be reading it in the first place); he expected me to think, to try to understand, and argue, and fight. And it was that expectation that drove me to books, more books, better books, books beyond the expectations of others. It made me a reader.

Which book hanged your life? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only humanities articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: A Wrinkle in Time. Trans Bodies, Trans Selves. The Beach. Wuthering Heights.

The post Which book changed your life? appeared first on OUPblog.

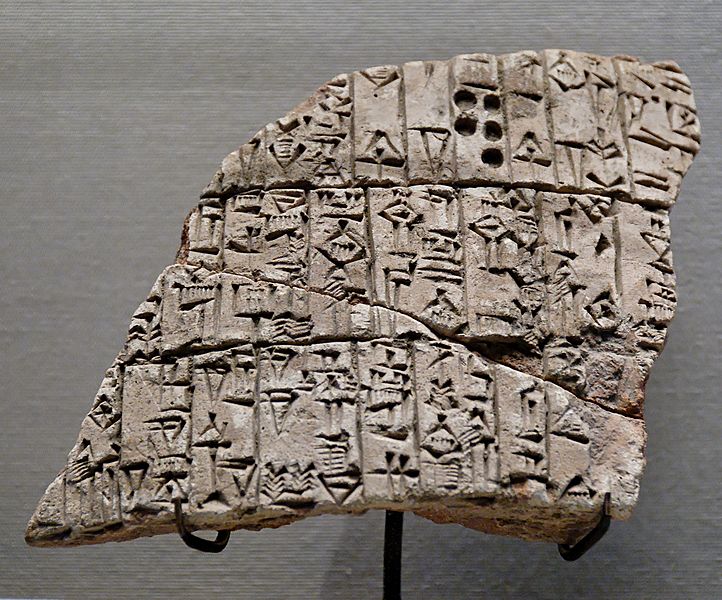

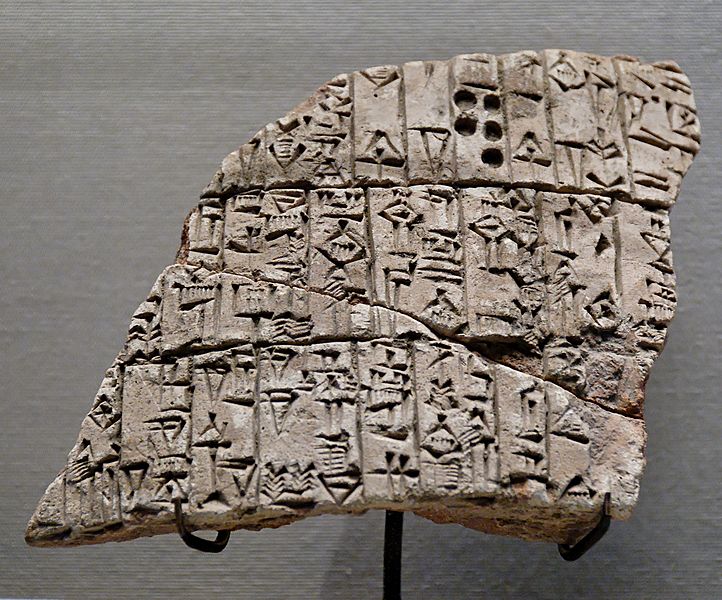

We’re continuing our discussion of what is a book today with some historical perspective. The excerpt below by Andrew Robinson from The Book: A Global History gives some interesting insight into how the art of writing began.

Without writing, there would be no recording, no history, and of course no books. The creation of writing permitted the command of a ruler and his seal to extend far beyond his sight and voice, and even to survive his death. If the Rosetta Stone did not exist, for example, the world would be virtually unaware of the nondescript Egyptian king Ptolemy V Epiphanes, whose priests promulgated his decree upon the stone in three scripts: hieroglyphic, demotic, and (Greek) alphabetic.

How did writing begin? The favoured explanation, until the Enlightenment in the 18th century, was divine origin. Today, many—probably most—scholars accept that the earliest writing evolved from accountancy, though it is puzzling that such accounts are little in evidence in the surviving writing of ancient Egypt, India, China, and Central America (which does not preclude commercial record-keeping on perishable materials such as bamboo in these early civilizations). In other words, some time in the late 4th millennium bc, in the cities of Sumer in Mesopotamia, the ‘cradle of civilization’, the complexity of trade and administration reached a point where it outstripped the power of memory among the governing elite. To record transactions in an indisputable, permanent form became essential.

Fragment of an inscripted clay cone of Urukagina (or Uruinimgina), lugal (prince) of Lagash. circa 2350 BC. terracotta. Musée du Louvre. Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Some scholars believe that a conscious search for a solution to this problem by an unknown Sumerian individual in the city of Uruk (biblical Erech), c .3300 bc, produced writing. Others posit that writing was the work of a group, presumably of clever administrators and merchants. Still others think it was not an invention at all, but an accidental discovery. Many regard it as the result of evolution over a long period, rather than a flash of inspiration. One particularly well-aired theory holds that writing grew out of a long-standing counting system of clay ‘tokens’. Such ‘tokens’—varying from simple, plain discs to more complex, incised shapes whose exact purpose is unknown—have been found in many Middle Eastern archaeological sites, and have been dated from 8000 to 1500 bc. The substitution of two-dimensional symbols in clay for these three dimensional tokens was a first step towards writing, according to this theory. One major difficulty is that the ‘tokens’ continued to exist long after the emergence of Sumerian cuneiform writing; another is that a two-dimensional symbol on a clay tablet might be thought to be a less, not a more, advanced concept than a three-dimensional clay ‘token’. It seems more likely that ‘tokens’ accompanied the emergence of writing, rather than giving rise to writing.

Apart from the ‘tokens’, numerous examples exist of what might be termed ‘proto-writing’. They include the Ice Age symbols found in caves in southern France, which are probably 20,000 years old. A cave at Pech Merle, in the Lot, contains a lively Ice Age graffiti to showing a stenciled hand and a pattern of red dots. This may simply mean: ‘I was here, with my animals’—or perhaps the symbolism is deeper. Other prehistoric images show animals such as horses, a stag’s head, and bison, overlaid with signs; and notched bones have been found that apparently served as lunar calendars.

‘Proto-writing’ is not writing in the full sense of the word. A scholar of writing, the Sinologist John DeFrancis , has defined ‘full’ writing as a ‘system of graphic symbols that can be used to convey any and all thought’—a concise and influential definition. According to this, ‘proto-writing’ would include, in addition to Ice Age cave symbols and Middle Eastern clay ‘tokens’, the Pictish symbol stones and tallies such as the fascinating knotted Inca quipus, but also contemporary sign systems such as international transportation symbols, highway code signs, computer icons, and mathematical and musical notation. None of these ancient or modern systems is capable of expressing ‘any and all thought’, but each is good at specialized communication (DeFrancis, Visible Speech, 4).

Andrew Robinson is the author of some 25 books in the arts and sciences including Writing and Script: A Very Short Introduction and Cracking the Egyptian Code: The Revolutionary Life of Jean-François Champollion. He is a contributor to The Book: A Global History, edited by Michael F. Suarez, S.J. and H. R. Woudhuysen.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only humanities articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post How did writing begin? appeared first on OUPblog.

In recent weeks, a trade dispute between Amazon and Hachette has been making headlines across the world. But discussion at our book-laden coffee tables and computer screens has not been limited to contract terms and inventory, but what books mean to us as publishers, booksellers, authors, and readers. So we thought this would be an excellent time to share some ideas on books from some of the greatest minds in our culture. Please share your personal thoughts in the comments below.

“A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us.”

–Franz Kafka, 1883-1924, Czech novelist

“A good book is the precious life-blood of a master spirit.”

–John Milton, 1608-74, English poet

“Books can not be killed by fire. People die, but books never die. No man and no force can abolish memory … In this war, we know, books are weapons. And it is a part of your dedication always to make them weapons for man’s freedom.”

–Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1882-1945, American Democratic statesman, 32nd President of the US 1933-45, and husband of Eleanor Roosevelt, ‘Message to the Booksellers of America 6 May 1942, in Publishers Weekly 9 May 1942

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live.”

–Joan Didion, 1934-, American writer, The White Album (1979)

“Some books are undeservedly forgotten; none are undeservedly remembered.”

–W.H. Auden, 1907-73, English poet

“Choose an author as you choose a friend.”

–Wentworth Dillon, Lord Roscommon, c. 1633-85, Irish poet and critic, Essay on Translated Verse (1684) l. 96

“No furniture is so charming as books.”

–Sydney Smith, 1771-1845, English essayist

“All books are either dreams or swords,

You can cut, or you can drug, with words.”

–Amy Lowell, 1874-1925, American poet, ‘Sword Blades and Poppy Seed’ (1914)

“Only connect! … Only connect the prose and the passion, and both will be exalted, and human love will be seen at its height.”

–E.M. Forster, 1879-1970, English novelist, Howard’s End (1910), ch. 22

“A good book is the best of friends, the same to-day and for ever.”

–Martin Tupper, 1810-89, English writer

“Some books are to be tasted, others to be swallowed, and some few to be chewed and digested.”

–Francis Bacon, 1561-1626, English courtier

“There is more treasure in books than in all the pirates’ loot on Treasure Island.”

–Walt Disney, 1901-66, American film producer

“There is no book so bad that some good cannot be got out of it.”

–Pliny the Elder, AD 23-79, Roman senator

“I hate books; they only teach us to talk about things we know nothing about.”

–Jean-Jacques Rousseau, 1712-78, French philosopher

“All books are divisible into two classes, the books of the hour, and the books of all time.”

–John Ruskin, 1819-1900, English critic

Ever since the first edition of the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations published over 70 years ago, this bestselling book has remained unrivalled in its coverage of quotations both past and present. Drawing on Oxford’s dictionary research program and unique language monitoring, over 700 new quotations have been added to this eighth edition from authors ranging from St Joan of Arc and Coco Chanel to Albrecht Durer and Thomas Jefferson.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post What is a book? appeared first on OUPblog.

Jonathan Kroberger, Publicist:

Jonathan Kroberger, Publicist:

Trans Bodies, Trans Selves, edited by Laura Erickson-Schroth

Trans Bodies, Trans Selves, edited by Laura Erickson-Schroth

Andy Allen, Marketing Manager:

Andy Allen, Marketing Manager:

Kirsty Doole, Publicity Manager:

Kirsty Doole, Publicity Manager:

Jacqueline Baker, Senior Commissioning Editor, Literature:

Jacqueline Baker, Senior Commissioning Editor, Literature: