After serving his country in Desert Storm, artist Andrew Robinson attended The Savannah College of Art and Design in the early 90′s. He bounced around the south-eastern states for a while before settling on the west coast in sunny Pasadena, CA. His early comics work first appeared in popular anthologies such as Dark Horse Presents, and Negative Burn.

In the late 90′s he created the critically acclaimed independent comic, Dusty Star, and started to get high profile cover work for DC Comics on titles such as Hawkman, and Starman.

He’s had a resurgence in his comics work of late, with a multitude of new cover illustrations in recent years for Marvel, DC, and Dark Horse, just to name a few. In addition to that, he illustrated the fully painted, award winning graphic novel, The Fifth Beatle: The Brian Epstein Story, which is set to be a major motion picture, soon.

To keep up with the latest news, and artwork by Andrew Robinson, you can go to his blog here.

For more comics related art, you can follow me on my website comicstavern.com - Andy Yates

We’re continuing our discussion of what is a book today with some historical perspective. The excerpt below by Andrew Robinson from The Book: A Global History gives some interesting insight into how the art of writing began.

Without writing, there would be no recording, no history, and of course no books. The creation of writing permitted the command of a ruler and his seal to extend far beyond his sight and voice, and even to survive his death. If the Rosetta Stone did not exist, for example, the world would be virtually unaware of the nondescript Egyptian king Ptolemy V Epiphanes, whose priests promulgated his decree upon the stone in three scripts: hieroglyphic, demotic, and (Greek) alphabetic.

How did writing begin? The favoured explanation, until the Enlightenment in the 18th century, was divine origin. Today, many—probably most—scholars accept that the earliest writing evolved from accountancy, though it is puzzling that such accounts are little in evidence in the surviving writing of ancient Egypt, India, China, and Central America (which does not preclude commercial record-keeping on perishable materials such as bamboo in these early civilizations). In other words, some time in the late 4th millennium bc, in the cities of Sumer in Mesopotamia, the ‘cradle of civilization’, the complexity of trade and administration reached a point where it outstripped the power of memory among the governing elite. To record transactions in an indisputable, permanent form became essential.

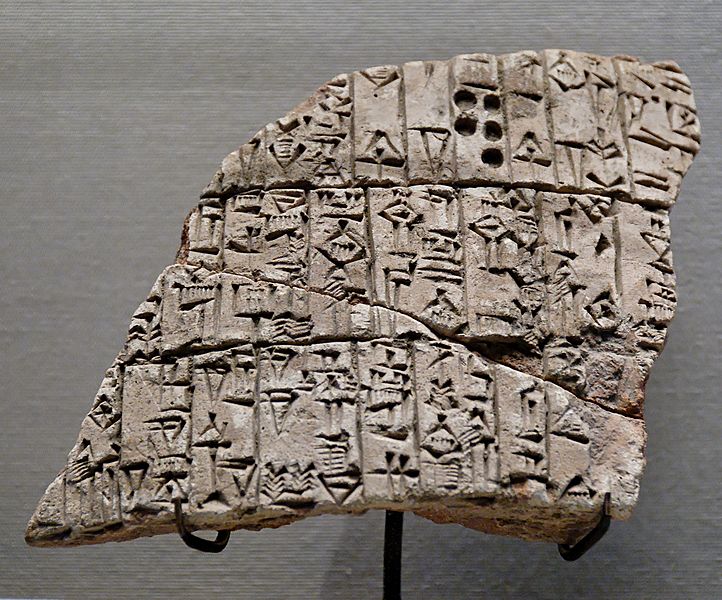

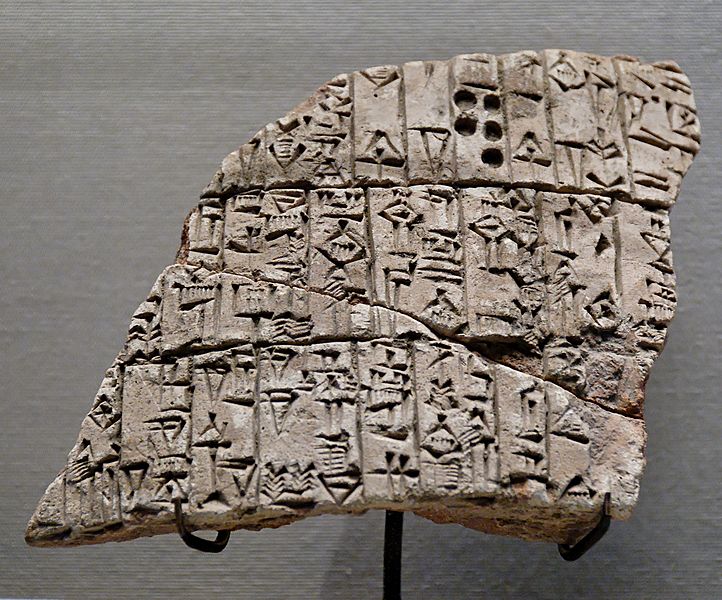

Fragment of an inscripted clay cone of Urukagina (or Uruinimgina), lugal (prince) of Lagash. circa 2350 BC. terracotta. Musée du Louvre. Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Some scholars believe that a conscious search for a solution to this problem by an unknown Sumerian individual in the city of Uruk (biblical Erech), c .3300 bc, produced writing. Others posit that writing was the work of a group, presumably of clever administrators and merchants. Still others think it was not an invention at all, but an accidental discovery. Many regard it as the result of evolution over a long period, rather than a flash of inspiration. One particularly well-aired theory holds that writing grew out of a long-standing counting system of clay ‘tokens’. Such ‘tokens’—varying from simple, plain discs to more complex, incised shapes whose exact purpose is unknown—have been found in many Middle Eastern archaeological sites, and have been dated from 8000 to 1500 bc. The substitution of two-dimensional symbols in clay for these three dimensional tokens was a first step towards writing, according to this theory. One major difficulty is that the ‘tokens’ continued to exist long after the emergence of Sumerian cuneiform writing; another is that a two-dimensional symbol on a clay tablet might be thought to be a less, not a more, advanced concept than a three-dimensional clay ‘token’. It seems more likely that ‘tokens’ accompanied the emergence of writing, rather than giving rise to writing.

Apart from the ‘tokens’, numerous examples exist of what might be termed ‘proto-writing’. They include the Ice Age symbols found in caves in southern France, which are probably 20,000 years old. A cave at Pech Merle, in the Lot, contains a lively Ice Age graffiti to showing a stenciled hand and a pattern of red dots. This may simply mean: ‘I was here, with my animals’—or perhaps the symbolism is deeper. Other prehistoric images show animals such as horses, a stag’s head, and bison, overlaid with signs; and notched bones have been found that apparently served as lunar calendars.

‘Proto-writing’ is not writing in the full sense of the word. A scholar of writing, the Sinologist John DeFrancis , has defined ‘full’ writing as a ‘system of graphic symbols that can be used to convey any and all thought’—a concise and influential definition. According to this, ‘proto-writing’ would include, in addition to Ice Age cave symbols and Middle Eastern clay ‘tokens’, the Pictish symbol stones and tallies such as the fascinating knotted Inca quipus, but also contemporary sign systems such as international transportation symbols, highway code signs, computer icons, and mathematical and musical notation. None of these ancient or modern systems is capable of expressing ‘any and all thought’, but each is good at specialized communication (DeFrancis, Visible Speech, 4).

Andrew Robinson is the author of some 25 books in the arts and sciences including Writing and Script: A Very Short Introduction and Cracking the Egyptian Code: The Revolutionary Life of Jean-François Champollion. He is a contributor to The Book: A Global History, edited by Michael F. Suarez, S.J. and H. R. Woudhuysen.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only humanities articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post How did writing begin? appeared first on OUPblog.

Where do geniuses come from? What makes a genius? Are all geniuses interesting people? Who’s more amazing, Shakespeare, Darwin or Einstein?

There are many questions about genius, and in his newest book, Sudden Genius? The Gradual Path to Creative Breakthroughs, Andrew Robinson answers all these and more.

About Sudden Genius

Click here to view the embedded video.

A Q&A with Andrew Robinson

Click here to view the embedded video.

Andrew Robinson was Literary Editor of The Times Higher Education Supplement from 1994-2006. His latest book is Sudden Genius? The Gradual Path to Creative Breakthroughs. He has written many other books including biographies of Albert Einstein, the film director Satyajit Ray, the writer Rabindranath Tagore, and the archaeologist Michael Ventris. He is also the author of Writing and Script: A Very Short Introduction, and Genius: A Very Short Introduction (forthcoming Spring 2011). You can read his previous OUPblog posts here (2009) and here (2010).

By Andrew Robinson

In the early 21st century, talent appears to be on the increase, genius on the decrease. More scientists, writers, composers, and artists than ever before earn a living from their creative output. During the 20th century, performance standards and records continually improved in all fields—from music and singing to chess and sports. But where is the Darwin or the Einstein, the Mozart or the Beethoven, the Chekhov or the Shaw, the Cézanne or the Picasso or the Cartier-Bresson of today? In the cinema, the youngest of the arts, there is a growing feeling that the giants—directors such as Charles Chaplin, Akira Kurosawa, Satyajit Ray, Jean Renoir, and Orson Welles—have departed the scene, leaving behind the merely talented. Even in popular music, genius of the quality of Louis Armstrong, The Beatles, or Jimi Hendrix, seems to be a thing of the past. Of course, it may be that the geniuses of our time have yet to be recognized—a process that can take many decades after the death of a genius—but sadly this seems unlikely, at least to me.

In saying this, I know I am in danger of falling into a mindset mentioned by the great 19th-century South American explorer and polymath Alexander von Humboldt, ‘the Albert Einstein of his day’ (writes a recent biographer), in volume two of his five-volume survey Cosmos. ‘Weak minds complacently believe that in their own age humanity has reached the culminating point of intellectual progress,’ wrote Humboldt in the middle of the century, ‘forgetting that by the internal connection existing among all the natural phenomena, in proportion as we advance, the field to be traversed acquires additional extension, and that it is bounded by a horizon which incessantly recedes before the eyes of the inquirer.’ Humboldt was right. But his explorer’s image surely also implies that as knowledge continues to advance, an individual will have the time to investigate a smaller and smaller proportion of the horizon with each passing generation, because the field will continually expand. So, if ‘genius’ requires breadth of knowledge, a synoptic vision—as it seems to—then it would appear to become harder to achieve as knowledge advances.

The ever-increasing professionalization and specialisation of education and domains, especially in the sciences, is undeniable. The breadth of experience that feeds genius is harder to achieve today than in the 19th century, if not downright impossible. Had Darwin been required to do a PhD in the biology of barnacles, and then joined a university life sciences department, it is difficult to imagine his having the varied experiences and exposure to different disciplines that led to his discovery of natural selection. If the teenaged Van Gogh had gone straight to an art academy in Paris, instead of spending years working for an art dealer, trying to become a pastor, and self-tutoring himself in art while dwelling among poor Dutch peasants, would we have his late efflorescence of great painting?

A second reason for the diminution of genius appears to be the ever-increasing commercialisation of the arts, manifested in the cult of celebrity. True originality takes time—at least ten years, as I show in my book Sudden Genius?—to come to fruition; and the results may well take further time to find their audience and market. Few beginning artists, or scientists, will be fortunate enough to enjoy financial support, like Darwin and Van Gogh, over such an extended period. It is much less challenging, and more remunerative, to make a career by producing imitative, sensational, or repetitious work, like Andy Warhol, or any number of professional scientists who, as Einstein remarked, ‘take a board of wood, look for its thinnest part, and drill a great number of holes when the drilling is easy.’

Thirdly, if less obviously, our expectations of modern genius have become more sophisticated and discriminating since the time of the 19th-century Romantic movement