Two hundred years ago, William Lawrence blew the roof off the Hunter Lecture Series at the Royal College of Surgeons by adding the word "biology" to the English language to discuss living physiology, behavior, and diversity as a matter of gunky chemistry and physics, sans super-added forces.

The post The true meaning of cell life and death appeared first on OUPblog.

As the popularity of creative nonfiction increases, the genre brings up an interesting debate: is every word supposed to be true? If events are recorded in a memoir, were they supposed to happen just that way? If a writer is investigating a true crime, is it okay for her to make up dialogue between the criminals if she gets really close to what was probably said? Recently, I read the book:

You Can't Make This Stuff Up by Lee Gutkind, who is the editor and founder of

Creative Nonfiction magazine. The book discusses what creative nonfiction is, provides popular examples done well, and instructs writers how to create a nonfiction piece.

Creative nonfiction is a nonfiction story that is told with fiction elements: dialogue, setting details, scenes, characterization (of real people), and so on.That's where the creative part is

supposed to come in--not in the facts but in HOW the facts are revealed.

Part one of Lee's book would be interesting to anyone who loves to read and discuss what they read. The author writes about some of the most infamous cases of writers who claimed to write a true, nonfiction account of their lives; when in all actuality, it was false—sometimes the entire story made up.

The account most people know about is James Frey and his book,

A Million Little Pieces, since Oprah chose it as one of her book club selections. Because of her recommendation, two million copies of his book sold, and Frey became a household name. Then it was discovered that most of his story was completely untrue. He did more than make up some dialogue or create a composite character for simplicity sake--Frey lied.

This is one of the extreme examples that Gutkind discusses in his book during the ethics section; but there are actually more writers (more than I realized!) that fudge the truth just a bit. But still, they claim that they write creative nonfiction. For example, David Sedaris admits that because he writes humor based on his life, that sometimes he must exaggerate or make up dialogue to get a laugh. Some of the funny lines in

Naked? Completely fabricated!

John Berendt made up dialogue and rearranged the story chronology in

Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil! Several people from Frank McCourt's home town claim that he didn't exactly tell the whole truth in

Angela's Ashes, and they state they've found over 100 discrepancies.

|

| A good example of the genre |

On his blog and in his book, Gutkind writes that he can accept some "exaggerating an event or situation, or compressing time periods, or creating composite characters" and that it "may possibly help a nonfiction writer make his or her point more effectively—although I believe this is only rarely truly necessary."

It’s a crucial decision for writers to make if they are going to tackle the genre: are they going to tell the truth without embellishments?

Personally, I was disappointed when reading this section of Lee's book--so many writers don't stick to the 100 percent truth. But then I thought maybe it's really difficult to do this--I don't write much in this genre, so maybe I don't know. I have written some essays, and I have included dialogue, and I think I have the dialogue right; but it's as I remember it--so who knows for sure?

How do you feel about this issue? How much of a creative nonfiction piece is it okay to "make up"? If you write memoir or creative nonfiction, do you create dialogue or make up characters, etc, to smooth transitions? As a reader, how do you trust the writer?

I started thinking that perhaps books should say on the cover: Based On a True Story--just like many movies do. . .

Margo L. Dill edits, blogs, writes, and teaches for WOW! Women On Writing. To view her upcoming classes in spring and summer (writing for children/teens, writing short fiction, writing a children's/YA novel), please visit the WOW! classroom: http://www.wow-womenonwriting.com/WOWclasses.html

Margo L. Dill edits, blogs, writes, and teaches for WOW! Women On Writing. To view her upcoming classes in spring and summer (writing for children/teens, writing short fiction, writing a children's/YA novel), please visit the WOW! classroom: http://www.wow-womenonwriting.com/WOWclasses.html

"No one better touch my cells!"

Oh, April, why have you flown by so quickly? It seems as though I was just settling into you and now we must say good-bye.

I did get a good amount reading in, though. I read A Breath of Eyre by Eve Marie Mont and Something Like Normal by Trish Doller (review pending).

I even finished reading Peter Pan (remember, Project Gutenberg is a goldmine for free public

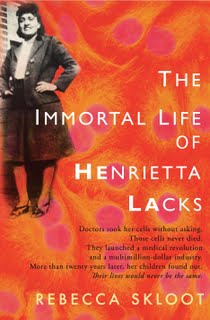

I'd never heard of Henrietta Lacks, pictured on the book cover, before I picked up Rebecca Skloot's wonderful book. Chances are, you haven't either. But you may have heard of HeLa cells or at the very least, information about medical research to find a polio vaccine or cure for cancer. In The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, you finally meet the women behind HeLa cells, “the first immortal cells ever grown in a laboratory,” as well as her family and key medical researchers.

The author first learned of HeLa when she was 16, and she soon grew fascinated by the story of Henrietta, an African-American woman, and her cells from a cervical cancer tumor. These cells have not only helped develop the polio vaccine and made important discoveries in fighting cancer, they've also led to advancements in gene mapping and in vitro fertilization.

What fascinated Skloot even more than HeLa cells and their contribution to scientific research is the story of Henrietta and her family. She was a poor Southern tobacco farmer who went to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland in the 1950s with cervical cancer. Doctors took a sample of her tumor without her knowledge or her family’s consent before she died.

The HeLa cells are still alive today and have multiplied into weighing more than 50 million metric tons—“as much as the Empire State Building.” Her family knew nothing about her cells being alive and helping modern medicine until the 1970s when doctors called her husband and children for research without informed consent.

By the time Skloot met Henrietta’s family members in the late 1990s and started interviewing them for her book, many of them, including her grown children, trusted no one, especially Caucasian reporters who wanted to know about Henrietta’s cancer cells. But because Skloot cared so much about Henrietta's story and knew it like her own, Henrietta's relatives started to trust her and share important information with her.

Besides introducing readers to Henrietta Lacks, her husband, and her children, Skloot skillfully informs readers about cell research and medical discoveries. Skloot also writes about the ethical issues, court cases, and laws surrounding these cells and other cell lines from patients, who didn’t realize that doctors were using them for research and making money from them. She takes a complex issue and writes about it so anyone can understand the science, medicine, and law. But more importantly, she intersperses the often heartbreaking personal story o

If there was a theme in what the many published writers said at the Austin SCBWI conference a couple weeks ago, it was that perseverance is an important part of their success.

Three of this year’s ALA winners were there — Jacqueline Kelly (The Evolution of Capurnia Tate), Marla Frazee and Liz Garton Scanlon (All the World illustrator and author) and Chris Barton (The Day-Glo Brothers) — and they all told tales of facing many rejections before publication and of pursuing their dreams of being published for years before making them a reality.

Kirby Larson, author of the 2007 Newbery Honor book Hattie Big Sky, said she received piles of rejection letters before her publishing career began. Finally, after many years of trying and taking a 10-day course that happened over her daughter’s birthday — what a sacrifice — she sold her first picture books. A few more followed, but then she didn’t sell anything for seven years. That’s when she tried a different type of writing and Hattie Big Sky was born.

Former editor and now full-time author Lisa Graff explained that for her last book, Umbrella Summer, she wrote 18 complete drafts.

Yesterday, this theme was reinforced in an article in the Los Angeles Times about non-fiction author Rebecca Skloot, whose The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks appeared on Amazon’s bestseller list immediately after the book debuted on Feb. 2. This was all after Skloot spent 10 years working on the book and went through three publishing houses, four editors and two agents.

All these writers shared something in common: They didn’t give up.

So, the motto for today: Never give up.

Write On!

0 Comments on Writers’ motto: Never give up as of 2/10/2010 1:32:00 PM

and I'm beginning with Katrina Kenison, who took a virtual walk with me this afternoon (we were on the phone; we live many states apart; I walked by this stream; I took a picture. Snap.). Katrina's newest book, The Gift of an Ordinary Day, came out this past fall and has been doing what thoughtful books do, over time—which is to say that it has been gaining momentum. Visit Katrina's web site. Watch the video she's made. Let her tell you about the life she has been living. You'll see why her book is touching so many lives, and why it's likely on its way to becoming a word-of-mouth bestseller.

and I'm beginning with Katrina Kenison, who took a virtual walk with me this afternoon (we were on the phone; we live many states apart; I walked by this stream; I took a picture. Snap.). Katrina's newest book, The Gift of an Ordinary Day, came out this past fall and has been doing what thoughtful books do, over time—which is to say that it has been gaining momentum. Visit Katrina's web site. Watch the video she's made. Let her tell you about the life she has been living. You'll see why her book is touching so many lives, and why it's likely on its way to becoming a word-of-mouth bestseller.

I'm moving next to Rebecca Skloot, whom I met years ago at Goucher College, when she was teaching, and her dad, Floyd, was teaching, and I was teaching—and it just went down like that: teachers teaching. Rebecca was talking even then about a book that she was writing, something, she kept saying, about the immortal cells of a woman named Henrietta Lacks. We talked about structure in the abstract back then, and over the next many years I either heard first-hand or read (on Rebecca's blog) about the journey she was taking with a book she so believed in that no amount of raised eyebrow on the part of ersatz publishers had the power to diminish. Rebecca had a story to tell. She had a story that defined her and defined us and had, she knew, to be told. She was in New York City writing, she was in her beat-up Honda driving, she was at a friend's farmhouse revising: Wherever she was, she was determined to get this story told.

You've heard of that Henrietta Lacks story in the meantime, right? You've heard Rebecca on ABC News, Rebecca on Fresh Air, Rebecca on All Things Considered. You've seen Rebecca in the pages of Oprah and let's not forget Rebecca three times in one week in the New York Times or Rebecca on her four-month book tour. We're talking about that Rebecca Skloot, my friends. The one who never stopped believing in her dream.

Finally, I am shouting out today on behalf of one of my very dearest friends, Alyson Hagy. We won a National Endowment for the Arts grant years ago. We started a correspondence. We're in touch, because I'm lucky, nearly every day, and Alyson has seen me through thick and thin, she has sent me her weather via email, she has cheered me through teaching because she's a teacher herself (the likes of whom Michael Ondaatje, Don DeLillo, Phillip Gourevitch, Joy Williams, and Edward Jones come to visit), and she has sent me early pages of her books to read because I so believe in her. Alyson's Ghosts of Wyoming came out a few days ago. It's already been featured, brilliantly, in the Boston Globe, The Believer, New West, and Denver Post, and do you want to know what Susan Salter Reynolds of the LA Times said about my friend Alyson this weekend? Do you?

Reynolds said this: These eight burnished stories confirm Hagy's importance in American literature; her seamless blending of landscape and lives, her very modern understanding of the vulnerability of kindness.

Yeah, baby. Oh, yeah.

Good questions. I think creative nonfiction, since it is based on our memories and perceptions, is always going to be partly fiction. That may be unintentional, but there are good reasons to intentionally alter truths, too. Like the example of exaggerating for humor. I've written creative nonfiction that is as close to the truth as I can get, but I've also written pieces that take several scenes and combine them into one, or take events out of order to make the story smoother. I like this quote from Pam Houston, who writes "fiction" but her stories seem mostly nonfiction: "Everything I write is 82% true."

Interesting discussion! I like how Ben Mezrich handled it in his book The Accidental Billionaires (the book they based the movie The Social Network on). He included an author's note in the beginning that said the book was a dramatic, narrative account based on dozens of interviews and hundreds of sources, and says that he uses literary techniques like re-created dialogue and scenes to move the story along. Because many of the conversations took place in different settings and over time, so he wanted to put them all together. So it's kind of like your movie disclaimer idea, and I liked that he was up front about it because the book is supposed to be nonfiction.

I feel nonfiction should be as true as possible, but I don't have the same expectations for memoir. I don't know why, but I guess it's because a good memoir is intimate. You get to see through a person's eyes and live through her flesh.

So I don't mind David Sedaris embellishing a bit in his stories--it's like a friend telling you what happened over dinner. There are those friends who tell a great story! And you often wonder if it's all completely true. But I think a book like The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks should be as accurate as possible because the author is uncovering an important scientific story about the start of the human cell cloning industry some sixty years ago, and involves an entire family over decades.

Those are just my feelings, and I don't know if they make sense or not. It makes you wonder if the person who invented the saying "Truth is stranger than fiction" wrote creative nonfiction!

Yes, I'd read before that David Sedaris has been known to "embellish" his work for humor's sake. And as one who frequently writes about the humorous goings on in my life, I think that's okay--as long as the gist of the event remains true. If you're making up an entire event, well, then, that's fiction and should be called such.

As for John Berendt, I was not okay with the way he manipulated the time line in his book. If he'd said, "based on true events", I wouldn't have minded so much. But he placed himself in the story AFTER certain events had transpired and he won awards as a non-fiction book.

I'm okay with a writer playing around with dialogue lines, but messing *with* events crosses the line.

I really enjoyed the questions you pose here, Margo. It is interesting that James Frey also claimed that he marketed his book originally as fiction and the publisher suggested they go memoir. I'm not sure if that's any truer than his memoir :)

Thanks for the insight here as I struggle with how (and if) to tell my life story.

Thanks for the comments, everyone. I do understand how hard it is to remember things factually--as in memoir or humor stories--we do the best we can according to our memory and as long as we aren't creating things like going to jail (I mean you just forgot you didn't go to jail?), I can see how the spirit of truth is there. And I agree books like Rebecca Skloot's should be as close to truth as humanly possible. I think my problem is 1. I'm naive 2. When I taught elementary school, we used to teach kids test taking skills. We told them that when answering true and false statements, if ANY PART of a statement was false, the ENTIRE STATEMENT was false. So. . .I guess that's where I am with all of this. I do think a disclaimer helps, somewhat.

Good discussion. I am reading one of Gutkind's other books right now, and exploring Creative nonfiction writing myself. I like what everyone else said. As close to true as is possible. When I read a supposed "creative" nonfiction book, I assume some dialogue or details are embellished, because unless you recorded those conversations, how could you possibly remember every word that was spoken!? I think if you get the gist of the scene correct, the feeling, and perhaps ask those people who are portrayed in the scene if you got it correct, then you're just about as close as you can get. Thanks for the post!

Humor writers get a certain amount of wiggle room, but if anyone else fudges dialogue or the timeline than it is fiction based on actual events. I don't care of you're John Berendt or Ben Mezrich. Maybe its because I came to this world via academia (history and archaeology/anthropology) but you do not fudge the date.