Mary Pope Osborne's Shadow of the Shark was published in 2015 as part of the best-selling Magic Tree House series. Osborne's Thanksgiving on Thursday did not fare well, here, at American Indians in Children's literature. Her Shadow of the Shark is just as bad. I tweeted as I read it, on September 15, 2016, made the tweets into a Storify (inserting comments between the tweets), and used the copy/paste function to paste the Storify here.

- Her name... doesn't it call to mind Disney's Pocahontas?!

- These goofy hyphenated Indian-sounding names (oh dang, I used a hyphen, too) are dreadful. So many writers come up with names like these for characters. But heck. A little research, please! Osborne could have looked for someone who speaks one of the Mayan languages, and found out what their word is for jaguar, and used that, right? Or a translation of it, from that language into English? Maybe Osborne thinks there's no Mayan people around? Surely, though.... doesn't she listen to, or read, national news? Like this story?

-

By: Debbie Reese,

on 7/21/2016

By: Debbie Reese,

on 7/21/2016

Blog: American Indians in Children's Literature (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Lane Smith, Pub Year 2015, There is a Tribe of Kids, Return to Augie Hobble, Add a tagA reader who was following the conversations about Lane Smith's There Is A Tribe of Kids wrote to ask me if I'd read his Return to Augie Hobble. Here's the synopsis:

Augie Hobble lives in a fairy tale―or at least Fairy Tale Place, the down-on-its-luck amusement park managed by his father. Yet his life is turning into a nightmare: he's failed creative arts and has to take summer school, the girl he has a crush on won't acknowledge him, and Hogg Wills and the school bullies won't leave him alone. Worse, a succession of mysterious, possibly paranormal, events have him convinced that he's turning into a werewolf. At least Augie has his notebook and his best friend Britt to confide in―until the unthinkable happens and Augie's life is turned upside down, and those mysterious, possibly paranormal, events take on a different meaning.

The synopsis doesn't say, but as I started reading about the book, I learned that it is set in New Mexico, which could (for me) be a plus. It could be a plus for kids in New Mexico, too, including Native kids.

But, the person who wrote to me told me that Return to Augie Hobble has some Native content in it, so I started reading the book itself, wondering what I'd find.

Scattered throughout are illustrations of one kind of another, all done by Smith. In chapter four, the main character, Augie, is out after dark in the woods nearby and has a fight with a wolf-like creature. The next morning Augie feels like his face has tiny splinters on it. He uses his moms razor to shave them off. As the illustration on the next page tells us, he's got bits of toilet paper on his chin and neck because he's nicked himself with that razor.

Augie gets to work early, so is sitting in the break area reading a comic, waiting for his shift to start. Moze, another employee arrives. Augie gets up, but (p. 68-69):He [Moze] pushes me back down. He calls me an Indian. I ask why and he says cause my face is under "Heap big TP." I say that doesn't even make sense so he hits me in the arm and says, "Teeeee Peeeeeee. Toilet paper, twerp." He goes, "Woo, woo, woo," and does a lame version of an Indian dance with an imaginary tomahawk. I say that's not very PC. He says "PC, Mac, who cares?" and hits me again.

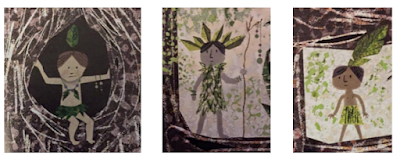

Interesting, isn't it? Let's look at that passage, in light of the discussions of his There Is a Tribe of Kids. The discussions are about some of the illustrations in the final pages of the book. Here's three:

Some wonder if Smith meant to depict kids playing Indian. Some say these kids aren't playing Indian. Smith hasn't responded (as far as I know) to any of the discussions. Some wonder if--as he drew the illustrations--he was aware that they could be interpreted as kids playing Indian. That wondering presumes that he is aware of the decades long critical writings of stereotyping, and in this case, stereotyping of Native peoples.

With Return to Augie Hobble, we know--without a doubt--that he does, in fact, know about issues of stereotyping.

How should we interpret that passage in Return to Augie Hobble?

Amongst the recent threads in writers' networks, is that if a writer is going to create a character who stereotypes someone, there ought to be some way (preferably immediately) for a reader to discern that it is a stereotype. One method is to have a bad-guy-character make the stereotypical remarks, because with them being delivered by a bad-guy, readers know they're not-good-remarks.

Does Smith do that successfully? I'll copy that passage here, for convenience (so you don't have to scroll back up):He pushes me back down. He calls me an Indian. I ask why and he says cause my face is under "Heap big TP." I say that doesn't even make sense so he hits me in the arm and says, "Teeeee Peeeeeee. Toilet paper, twerp." He goes, "Woo, woo, woo," and does a lame version of an Indian dance with an imaginary tomahawk. I say that's not very PC. He says "PC, Mac, who cares?" and hits me again.

In the passage above, it is Moze (a bad guy character) who is speaking. From "hits me again" the narrative leaves this whole Indian thing behind as they talk about other things.

I find the passage confusing. It feels like there's something missing between "Toilet paper, twerp." and "He goes, "woo, woo, woo," and does a lame version of an Indian dance with an imaginary tomahawk." What do you think? Is something missing there?

Confusion aside, I think the passage doesn't do what, I assume, Smith meant it to do. Moze is delivering remarks in that humorous style Smith is praised for using. Will kids pick up on his message (assuming he meant to use Moze to teach kids that dancing around that way is not ok)? Or, does his "PC, Mac" get in the way of that understanding? With "PC, Mac" the focus is on computers, not stereotypes. That kind of word play is a big reason people like Smith's writing.

Back when I taught children's literature at the University of Illinois, I selected Smith's The True Story of the Three Little Pigs as a required reading. It is a terrific way to teach kids about differing points of view. When I think about that book, I know that Smith understands different points of view and how they matter.

I think it fair to say Lane Smith is a master at conveying the importance of that all important point of view. As his Augie Hobble tells us, he's aware of problems with the ways that Native peoples are depicted. That is part of why I find his There Is a Tribe of Kids disappointing.

What are you thoughts? Knowing he is aware of issues of stereotyping, what do you make of what he did in There Is a Tribe of Kids? And, does what he did in Augie Hobble work?

__________

From time to time I curate a set of links about a particular book or discussion. I'm doing that below, for There Is a Tribe of Kids. The links are arranged chronologically by date on which they were posted/published. If you know of ones I ought to add, please let me know. I will insert it below (as you'll see, I'm noting the date on which I add it to the list in parenthesis).

Sam Bloom's Reviewing While White: There Is a Tribe of Kids posted on July 8, 2016 (added to this list on July 21, 2016).

Debbie Reese's Reading While White reviews Lane Smith's THERE IS A TRIBE OF KIDS posted on July 9, 2016 (added to this list on July 21, 2016).

Debbie Reese's Lane Smith's new picture book: THERE IS A TRIBE OF KIDS (plus a response to Rosanne Parry) posted on July 14, 2016 (added to this list on July 21, 2016).

Roxanne Feldman's A Tribe of Kindred Souls: A Closer Look at a Double Spread in Lane Smith's THERE IS A TRIBE OF KIDS posted on July 17, 2016 (added to this list on July 21, 2016).

Roger Sutton's Tribal Trials posted on July 18, 2016 (added to this list on July 21, 2016).

Elizabeth Bird's There Is a Tribe of Kids: The Current Debate posted on July 19, 2016 (added to this list on July 21, 2016).0 Comments on Does Lane Smith's RETURN TO AUGIE HOBBLE tell us anything about his THERE IS A TRIBE OF KIDS? as of 7/21/2016 12:35:00 PMAdd a Comment By: Debbie Reese,

on 3/16/2016

By: Debbie Reese,

on 3/16/2016

Blog: American Indians in Children's Literature (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Joseph Bruchac, recommended, Tribal Nation: Abenaki, Reviewer: Beverly Slapin, Pub Year 2015, The Hunter's Promise, Add a tagEditor's Note: Beverly Slapin submitted this review essay of Joseph Bruchac's The Hunter's Promise. It may not be used elsewhere without her written permission. All rights reserved. Copyright 2016. Slapin is currently the publisher/editor of De Colores: The Raza Experience in Books for Children.~~~~~Bruchac, Joseph (Abenaki), The Hunter’s Promise: An Abenaki Tale, illustrated by Bill Farnsworth. Wisdom Tales (2015), kindergarten-upWithout didacticism or stated “morals,” Indigenous traditional stories often portray some of the Original Instructions given by the Creator, and children (and other listeners as well), depending on their own levels of understanding, may slowly come to know the stories and their embedded lessons.Bruchac’s own retelling of the “Moose Wife” story, traditionally told by the Wabanaki and Haudenosaunee peoples of what is now known as the Northeastern US and Canada, is a deep story that maintains its important teaching elements in this accessible children’s picture book.Here, a young hunter travels alone to winter camp to bring back moose meat and skins. Lonely and wishing for companionship, he finds the presence of someone who, unseen, has provided for his needs: in the lodge a fire is burning, food has been cooked, meat has been hung on drying racks and hide has been prepared for drying. On the seventh day, a mysterious woman appears, but is silent. The two stay together all winter and, when spring arrives and the hunter leaves for his village, the woman says only, “promise to remember me.”As the story continues, young readers will intuit some things that may not make “sense.” Why does the hunter travel alone to and from winter camp? Why doesn’t the woman return with the hunter to the village? Why do their children grow up so quickly? Why does she ask only that the hunter promise to remember her? Who is she really? The story’s end is deeply satisfying and will evoke questions and answers, as well as ideas about how this old story may have connections to contemporary issues involving respect for all life.Farnsworth’s heavily saturated oil paintings, with fall settings on a palette of mostly oranges and browns; and winter settings in mostly blues and whites, evoke the seasons in the forested mountains and closely follow Bruchac’s narrative. Cultural details of housing, weapons, transportation and clothing are also well done. The canoes, for instance, are accurately built (with the outside of the birch bark on the inside); and the women’s clothing display designs of quillwork and shell rather than beadwork (which would have been the mark of a later time).That having been said, it would have been helpful to see representations of individual characteristics and emotion in facial expressions here. While Farnsworth’s illustrations aptly convey the “long ago” in Bruchac’s tale, this lack of delineation evokes an eerie, ghost-like presence that may create an unnecessary distance between young readers and the Indian characters.Bruchac’s narrative is circular, a technique that might be unfamiliar with some young listeners and readers who will initially interpret the story literally as something “only” about loyalty and trust in human familial relationships; how these ethics encompass the kinship of humans to all things in the natural world might come at another time. I would encourage classroom teachers, librarians and other adults who work with young people to allow them to sit with this story. They’ll probably “get” it—if not at the first reading, then later on.And I would save Bruchac’s helpful Author’s Note for afterthe story, maybe even days or weeks later:It’s long been understood among the Wabanaki…that a bond exists between the hunter and those animals whose lives he must take for his people to survive. It is more than just the relationship between predator and prey. When the animal people give themselves to us, we must take only what we need and return thanks to their spirits. Otherwise, the balance will be broken. Everything suffers when human beings fail to show respect for the great family of life.—Beverly Slapin0 Comments on Beverly Slapin's Review of Bruchac's THE HUNTER'S PROMISE: AN ABENAKI TALE as of 1/1/1900Add a Comment By: Debbie Reese,

on 2/25/2016

By: Debbie Reese,

on 2/25/2016

Blog: American Indians in Children's Literature (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Pub Year 2015, Debbie--have you seen, not reviewed, A Choctaw Pony Survivor, Dream a Pony Wake a Spirit: The Story of Buster, Sarah Dickson Silver, Add a tagSarah Dickson Silver's Dream a Pony: Wake a Spirit: The Story of Buster, a Choctaw Pony Survivor, is on my to-read list this year. Published in 2015 by Luminare Press, here's the synopsis:

In the Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory, in the year 1900, friendships between children of white “intruders” and their Choctaw and Chickasaw schoolmates had to cross a deep cultural divide. It was also a time when public ignorance could make a mockery of the ambitions of a boy with dwarfism and a place where children had to grow up fast. Trouble begins when a beautiful wild stallion, a supposed man killer, is rescued by two adventurous young brothers. When the stallion is identified as a rare Choctaw horse, the question of who should own him threatens to destroy cherished friendships. Then a courageous decision by a young boy allows the ancient spirit of Buster, their Choctaw Pony survivor, to live on for future generations to love and respect.

If I am able to read it, I'll be back with a review.0 Comments on Debbie--have you seen... Sarah Dickson Silver's DREAM A PONY, WAKE A SPIRIT: THE STORY OF BUSTER: A CHOCTAW PONY SURVIVOR as of 2/25/2016 12:21:00 PMAdd a Comment By: Debbie Reese,

on 1/15/2016

By: Debbie Reese,

on 1/15/2016

Blog: American Indians in Children's Literature (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: not recommended, Talasi, Pub Year 2015, Ellen S. Cromwell, Add a tagEarlier this month I received a review copy of Talasi, A Story of Tenderness and Love. Written by Ellen S. Cromwell and illustrated by Desiree Sterbini, it purports to be about a Hopi child. The author is not Native.

Here's some of my notes:

Page 6

Talasi is the little girl's name, which, the author tells us "comes from corn tassel flowers that surround her pueblo home in Arizona."

I think readers are meant to think that her name may be a Hopi name. Let's pause, though, and think about that. The word tassel is an English word. The Hopi have their own language, and likely have a word for tassel. Wouldn't the child's name reflect that word rather than the English one?

As regular readers of American Indians in Children's Literature know, my grandfather is Hopi. I've been to Hopi. Homes on the mesas aren't surrounded by corn fields. The mesas are, so maybe that is what the author means, but written as-is, it reminds me more of farms in the midwest where homes are surrounded by corn fields.

Page 7

There's an error about materials used to build homes. The text says that "dwellings" (that word, by the way, sounds like an anthropologist, not a storyteller) are made from "adobe stone and clay." That ought to be "dried bricks and adobe clay" as stated in the "About the Hopis" at the end of the book.

We read that the best part of "multi-level living" is that Talasi can climb up and down a ladder. Sounds odd to me... let's think about a child in the midwest living in a two-story house. Is that child likely to say going up and down the stairs is the best thing about living in that multi-level home? I doubt it. Presenting that activity as a favorite thing for Talasi to do sounds very much like an outsider's imaginings of what life is like for a Hopi child. I suppose it is possible, but, not likely.

Page 10

The illustration shows Talasi and her grandmother, who sits in a rocking chair. The wall behind them has a six-paned glass window... which strikes me as an inconsistency. So does Talasi lying on the floor. It reminds me of a modern day house (again, in the Midwest) more than it does a Hopi home at one of the mesas. It also makes me wonder about the time period for this story.

On that page Talasi's grandmother tells her that she's going to move to a new home and that she'll go to a school to learn things that she (the grandmother) can no longer teach her. This foreshadows what is to come: Talasi's grandmother is going to die and upon her death, Talasi and her mom are going to move away to a city.

Page 14-15

On this page we have a double paged spread showing a city with tall buildings and bright lights. I wonder if it is Phoenix? And again I wonder about the time period for the story.

Page 16

Talasi goes to school but feels out of place. The text says that there are things to play with, but "no Katsina dolls to comfort her." Reading that, I hit the pause button. This, again, feels very much like an outsider voice. A "Katsina doll" isn't a plaything in the way that sentence suggests.

Page 18

Talasi brings a Katsina doll into the classroom. She wants to share it, and a story about it. I find that page especially troubling. It makes me wonder if Cromwell and Sterbini submitted this project to the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office. The acknowledgements page in the front of the book thanks Stewart B. Koyiyumptewa, the archivist at HCPO, for his "generous attention." His name there suggests that he endorsed Cromwell's book, but "generous attention" gives me pause. Given the care with which the HCPO protects Hopi culture from appropriation and misrepresentation, I doubt that HCPO approved what I see on page 18.

That said, the way that Talasi tells that story sounds--again--very much like an adult who is an outsider rather than how a Hopi child would speak.***I have too many concerns about the content of Talasi, A Story of Tenderness and Love. If I hear from any of the people in the Acknowledgements, telling me that they do recommend it, I'll be back to say so.0 Comments on Ellen S. Cromwell's TALASI, A STORY OF TENDERNESS AND LOVE as of 1/1/1900Add a Comment By: Debbie Reese,

on 1/5/2016

By: Debbie Reese,

on 1/5/2016

Blog: American Indians in Children's Literature (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: not recommended, Stephanie Shaw, Pub Year 2015, The Legend of the Beaver's Tail, Add a tagToday's post is one that walks you (readers of AICL) through my evaluation process (what I do) when I pick up a book that is put forth as a Native "legend."

The focus of today's post? The Legend of the Beaver's Tail "as told by" Stephanie Shaw, with illustrations by Gijsbert van Frankenhuyzen. It was published in 2015 by Sleeping Bear Press. As the note above the cover indicates, I do not recommend it.

First comment

See the word "legend" in the title? The word "legend" is often used to describe Native stories. It is one of those catch-all words that should be used in a universal way (applied to all peoples stories) but isn't.

Let's pause here. I'd like you to think about all the Bible legends you've read in the children's picture book format. Can't think of one? You're not alone. Most of the stories from the bible are not treated as "legends."

If you look up the definition of legend, you'll find the word is used to describe an old story. You're not likely to find "sacred" as part of that definition. Bible stories are old, but they don't get categorized as legends because they're sacred to the people who tell them.

Native stories are as sacred to Native people as Christian stories are to Christians. I view the selective use of "legend" as the outcome of a long history of Christians putting Native people forward as "other" to Christianity, with Christianity as THE religion that matters. Those "other" religions aren't religions at all in that Christian point of view. Instead, they're less-than, primitive, superstitious, quaint... You get the point.

So--when I see "legend" used to describe a Native story, I wonder if the person telling that story (or retelling it) is aware of the bias that drives that person to use the word "legend."

Second comment

Who is this "legend" supposed to be about? Who tells it? The front cover doesn't tell us. Neither does the back cover. On the copyright page, we read this summary:"Vain Beaver is inordinately proud of his silky tail, to the point where he alienates his fellow woodland creatures with his boasting. When it is flattened in an accident (of his own making), he learns to value its new shape and seeks to make amends with his friends. Based on an Ojibwe legend." --Provided by publisher.

Let's consider that last line: "Based on an Ojibwe legend." A lot of those "based on" books for children--the ones about Native people--draw from more than one Native nation's stories. A good example are the ones by Paul Owen Lewis. He used stories from more than one nation to come up with Frog Girl and Storm Boy. On his website, you can read that"Storm Boy follows the rich mythic traditions of the Haida, Tlingit, and other Native peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast..."

Those are distinct nations with their own stories. If you look at his books, they look like they are Native stories, but are they? If they combine aspects of more than one tribal nation? My answer: No. Let's look just at two that Lewis listed: the Haida and the Tlingit. In the US (in Alaska) there is the Central Council of the Tlingit & Haida Indian Tribes. At their website, you read that they're "two separate and distinct people" and there's also the Yakutat Tlingit Tribe (their direct website is down), also in Alaska. And in Canada, there's the Haida Nation.

The difference in the books Lewis does and Shaw's story is that he names several nations and she names one (Ojibwe). Does that make a difference? Maybe... let's keep on with this evaluation process.

Third comment

Who is Stephanie Shaw? Is she Native? With the "as told by" on the cover, do we have a story being told by a tribal member? At her website, I see that she lives in Oregon, but there is no mention of any Native heritage or working with Native populations or attending Native events... Nothing. None of her other books are about Native people. I assume then, that she is not Native. I wonder what prompted her to do this book?

As some of you know, I do not insist that a writer be Native in order to write Native stories. As I discussed elsewhere, I prefer Native writers, but I also think that a person who is not Native can write a Native story, and do it well--if they are careful with their research. Wondering about Shaw's research leads to my fourth comment.

Fourth Comment

What does Shaw say about her sources? Have you read Betsy Hearne's article, Cite the Source, Reducing Cultural Chaos in Picture Books, published in School Library Journal in 1993? An excellent article, it was a call for better source notes. It includes a "source note countdown" that can help reviewers evaluate a source note. The worst kind of note is nonexistent. It is #5 in Hearne's countdown. The best kind is #1, "the model source note."

So... let's look at the notes in Shaw's book.

There is a page in the back of the book titled "The Ojibwe People and Legends." Beneath it is a bibliography. Let's start with the note about Ojibwe people. The first paragraph tells us about various spellings of Ojibwe. The second paragraph is this:Legends are an important part of Ojibwe culture. They are stories passed from one generation to the next, usually through oral storytelling. They are sometimes meant just for fun and entertainment. Other times they are used to teach a lesson about behavior. In a legend such as The Legend of the Beaver's Tail, we learn about how pride and boastful behavior can drive friends away. We also learn how sharing among friends can build a community.

It starts with that word (legend). I've already said a lot about it, but I invite you to read that paragraph, with Christianity in mind. Some of what we read in the Bible are stories about behavior. Can you think of a picture book that presents one of those stories as a legend?

Now let's look at the bibliography.

It consists of eleven items. Seven of them are about beavers. I assume Shaw and perhaps her illustrator, Gijsbert van Frankenhuyzen, used those items for information about beavers. The other four (two books and two websites), I assume, are sources for what she provides about Ojibwe people. Let's take a look.

She lists Joseph Bruchac and Michael J. Caduto's Native American Stories published in 1991 by Fulcrum. It doesn't have an Ojibwe story about beaver. Shaw also lists Michael G. Johnson and Richard Hook's Encyclopedia of Native Tribes of North America published in 2007 by Firefly Books. I don't know that book, but from what I can see, it doesn't have a story about beaver in it.

She lists First People--the Legends. "How the Beaver Got His Tail." Accessed December 11, 2012, at www.firstpeople.us/FP-Html-Legends/HowTheBeaverGotHisTail-Ojibwa.html. I've been to that site before--and cringed. You're invited to "Click on my little kachina friends" to see what has recently been added to the site. Yikes! "Little kachina friends" is way over the line. Think of it like this: "Click on my little Catholic saint friends below..." instead. Feel uneasy? That's how I feel as I read "my little kachina friends." I wonder who wrote "my little kachina friends"? We don't know who owns, manages, or writes the content of that "First People" site. They use the word "we" a lot but who is "we" anyway?! They've got a section called "our favorite artists that paint Native Americans" --- but the ones they list aren't Native artists. Unless you're doing a study of appropriation, I think this site is one to stay away from. She also lists Native Languages of the Americas, a site maintained by Orrin Lewis and Laura Redish. Though we do know who runs that site, its content is unreliable. Like the First People site, I've looked it over before and found it lacking. According to the site, Lewis is Cherokee and not as involved with the content as he once was. Redish is not Native. I don't see any Ojibwe stories there, either.

Maybe the bibliography isn't one that Shaw developed. Maybe that page was put together by someone at the publishing house. Either way, it is troubling to see what gets listed in a book, as information to pass along to children.

Applying Hearne's countdown, I think Shaw's notes are at the not-good end of the scale:4. The background-as-source-note. Better than nothing but still close to useless, this note gives some general information on the culture from which a picture-book folktale is drawn. It's important to know about traditions, but that's a background note, not a source note. In some ways, it's worse than no note at all because it's deceptive. It looks like a source note, so we let it slide by. Some notes (variation 4A) even manage to tell the history of a tale but avoid citing the book or books from which the tale was adapted. Others (variation 4B) declare that the picture-book author heard many stories from his/her grandmother/grandfather, but beg the question of where he/she heard/read this particular story. Implication is a sneaky and highly suspicious maneuver. Source notes, once and for all, tell sources. How can we know what's been adapted without being able to track down the author/artist's source?

Fifth comment

I imagine you're wondering, "well, what about the story itself?" The answer? It doesn't matter. Shaw may have told what some think is a terrific story, but without the information to support that story, it doesn't matter. It is introducing or affirming the chaos Hearne wrote about in her article.

Conclusion: Not recommended

If you care about providing young people with authentic or accurate stories about Native people, this one won't work.

0 Comments on Stephanie Shaw's THE LEGEND OF THE BEAVER'S TAIL as of 1/1/1900Add a Comment