new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Plot Points, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 6 of 6

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Plot Points in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

Matthew Jockers, a University of Nebraska English professor, thinks that there are about six or seven basic plot shapes to any novel.

Jockers came to this conclusion through “microanalysis,” the process of analyzing texts using computers and mapping the shape of the plot in various works of fiction. On his blog he analyzes James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as an example to demonstrate his logic and process. Check it out:

In addition to this mathematical approach, I also employed good old subjective evaluation. The tool suggested six or seven, but this number (six, seven) would be rather useless if the resulting shapes did not make any sense to those of us who actually read the books. So, I looked at a lot of plots; everything from two to twenty.

You can check out a video of Jockers’ describing his digital text mining process here. (Via VICE.)

By:

Darcy Pattison,

on 7/22/2014

Blog:

Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

novel,

scene,

plotting,

write,

revise,

action,

Novel Revision,

plot points,

off-stage,

Add a tag

The ALIENS have landed!

"amusing. . .engaging, accessible," says Publisher's Weekly

|

|

|

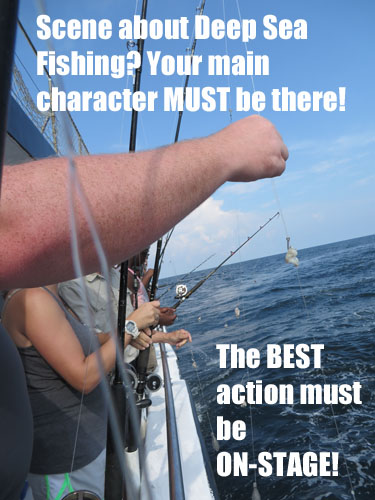

Here’s a common problem that I see in first drafts: the main action has happened off-stage.

Think about Scarlett O’Hara and the other southern women sitting at home waiting; in an attempt to avenge his wife, Frank and the Ku Klux Klan raid the shanty town whereupon Frank is shot dead. But the raid takes place off-stage.

Or, think about times when a weaker character stays home, while the adventurous character is off doing something. Sports stories are hard when the POV character is watching the on-field action.

This can be a real trap for children’s novels if an older sibling or parent is doing something fun/exciting/scary/etc off stage.

Another challenging situation is when a bully is planning something and the POV victim is just trying to avoid that.

Or, maybe you’ve planned a great scene, and the main character is present, but you don’t write that scene. Instead, what you write is something like this: “The next morning, Elise lay in bed and went over the previous night in her head.”

No. That doesn’t work!

Does this always need to be changed? No. But it’s a major problem and challenge as you revise. Here are some tips.

Recognize the problem. As you write the first draft and revise it, you should be evaluating the scenes. Ask: Who hurts the most in this scene. It should almost always be the main character. If it’s someone else, why isn’t THAT character the hero/ine of the story?

Put the POV Character in the action. When you find a scene where the main action is off-stage, look for ways to rethink the plot and scenes and put the main character in the thick of the action. It’s why Captain Kirk leaves the Enterprise and goes down to the planet over and over and over. Really? No Captain would be allowed to jeopardize his life that much and give over the control of the ship to a junior officer. It’s unrealistic–but great storytelling.

Make the story about how the off-stage action affects the POV character. In Gone with the Wind, Frank and the other men go off to avenge Scarlett’s honor, but the POV stays firmly with Scarlett. It’s about her growing realization of what the men have gone off to do, the opinion of the other women, and eventually the women’s reactions when the men come back. This is a risky way to write a scene, because the real stuff happens off stage; but it can work if you keep the focus right.

Write the scene. If your character is just thinking about what happened last night, it’s a simple fix. Write the @#$@#$@# scene! Sometime this happens when the author is afraid of the emotions in a powerful scene; the author avoids writing that scene and tries to jump forward in time. It never works. You must write the scene that you fear. you must write the exciting scene because your reader demands it; that is the exact reason why they come to your story. Don’t cheat them out of the emotionally experience.

Lately I’ve been having a hard time finishing books. Not because the writing is bad, or the stories don’t have developed characters, or even interesting plots. The problem is the stories don’t grip me and I’m not compelled to pick them up again to see what happens next.

With so many distractions in life – television, facebook, cooking classes – it’s easy to put a book down and stop reading. This is a reality we all must face. So, how do we keep our readers hooked? How do we make it impossible for them to put the story down?

Of course there are a lot of possible answers to that question, but the one I want to talk about today is The Gap.

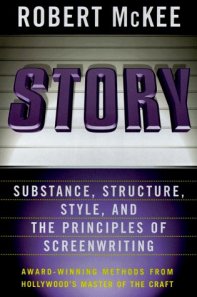

The Gap is a concept coined by Robert McKee in his craft book STORY, wherein he argues that we read because we want to see characters presented with situations that “pry open a gap” in their lives. He describes the Gap as a moment in a character’s life when the world acts in a way that surprises them. It’s a revelation and/or situation in which the character’s landscape operates outside of what they knew was possible.

For example, a tornado headed straight for your character’s house is a gap in their life. Normal life has been interrupted by mother nature and now your character must act. But a gap can also be as small as the “cool kids” deciding to talk to your character at school. It’s any event that tilts your character’s landscape in a new way and presents your character with new opportunities and obstacles. At least, on the surface that’s what a Gap is.

But let’s talk about how to maximize the Gap and make your stories un-put-downable!

McKee describes the Gap this way:

“The protagonist seeks an object of desire beyond his reach. Consciously or unconsciously he chooses to take a particular action, motivated by the thought or feeling that this act will cause the world to react in a way that will be a positive step toward achieving his desire. From his subjective POV the action he has chosen seems minimal, conservative, yet sufficient to effect the reaction he wants. But the moment he takes action, the objective realm of his inner life, personal relationships, or extra-personal world, or a combination of these, react in a way that’s more powerful or different than he expected … his action provokes forces of antagonism that open up the gap between his subjective expectation and the objective result, between what he thought would happen when he took his action and what in fact does happen … The gap is the point where the subjective and objective realms collide, the difference between anticipation and result, between the world as the character perceived it before acting and the truth he discovers in action.” (McKee, Story)

“The protagonist seeks an object of desire beyond his reach. Consciously or unconsciously he chooses to take a particular action, motivated by the thought or feeling that this act will cause the world to react in a way that will be a positive step toward achieving his desire. From his subjective POV the action he has chosen seems minimal, conservative, yet sufficient to effect the reaction he wants. But the moment he takes action, the objective realm of his inner life, personal relationships, or extra-personal world, or a combination of these, react in a way that’s more powerful or different than he expected … his action provokes forces of antagonism that open up the gap between his subjective expectation and the objective result, between what he thought would happen when he took his action and what in fact does happen … The gap is the point where the subjective and objective realms collide, the difference between anticipation and result, between the world as the character perceived it before acting and the truth he discovers in action.” (McKee, Story)

Creating a Gap for your characters isn’t as simple as throwing obstacles in the character’s way and hoping for drama. A compelling Gap will present your character with a situation that demands they make a difficult choice. This choice should be one that isn’t easy to run away from. I should “trap” your character and not allow them to return to their normal way of life. This is the space in which characters grow. It’s the space in which plot becomes so intoxicating your reader cannot put the book down.

Why? Because we want to see what choice the character will make. And, we want to see the consequences of their actions.

McKee goes on to say that:

“Once the gap in reality splits open, the character, being willful and having capacity, senses or realizes that he cannot get what he wants in a minimal, conservative way. He must gather himself and struggle through the gap to take a second action. This next action is something the character would not have wanted to do in the first case because it not only demands more willpower and forces him to dig more deeply into his human capacity, but most important the second action puts him at risk. He now stands to lose in order to gain.” (McKee, Story)

Okay, let’s look at an example to help illustrate this idea.

One of my favorite examples of a compelling Gap is in the reaping scene in The Hunger Games. As writers we have a lot of choices to make in our novels. Hunger Games author, Susan Collins, could have chosen to have Katniss’s name pulled out of the reaping basket. This would have presented a Gap in Katniss’s life. She would be presented with the choice of accepting the challenge of the games or running away and putting her family in danger. But Susan Collins makes the Gap even more intense and unimaginable for Katniss. Instead of pulling Katniss’s name from the reaping basket, her sister Primm’s name is pulled. Now the world has really opened up and torn a Gap in Katniss’s life. The world has truly acted in a way she did not see coming.

The Gap forces Katniss to choose between staying alive and watching her sister go off to die, or choosing to volunteer in her sister’s place and fight to the death. Neither decision is a good one. If you were forced to put the book down at that moment, before Katniss made her decision, don’t you think you would be itching to get back to reading? YES! Of course you want to see what choice she will make. This is the stuff of great drama!

Another great example of Gaps is the movie Sunshine. This is a lesser known sci-fi film directed by Danny Boyle and written by Alex Garland. Every action, decision, and plot point in this movie has a consequence that forces the characters to face a new Gap. The film follows the crew of ICARUS 2, a spaceship flying toward Earth’s dying sun in hopes of “rebooting” it with a nuclear bomb. ICARUS 1 failed its mission in the past and ICARUS 2 is Earth’s last and final hope before the planet dies from lack of sunshine. The first gap in the film comes when ICARUS 2 receives a distress signal from ICARUS 1. The crew is now forced to make a choice. Do they alter their course to intercept ICARUS 1 and get a second “payload” bomb to help re-boot the sun, thus allowing them two chances for mission success, or do they stay on course and gamble that the one payload they have is enough? It’s not an easy decision. Both choices have consequences. As a reader we want to see what they will do!

Another great example of Gaps is the movie Sunshine. This is a lesser known sci-fi film directed by Danny Boyle and written by Alex Garland. Every action, decision, and plot point in this movie has a consequence that forces the characters to face a new Gap. The film follows the crew of ICARUS 2, a spaceship flying toward Earth’s dying sun in hopes of “rebooting” it with a nuclear bomb. ICARUS 1 failed its mission in the past and ICARUS 2 is Earth’s last and final hope before the planet dies from lack of sunshine. The first gap in the film comes when ICARUS 2 receives a distress signal from ICARUS 1. The crew is now forced to make a choice. Do they alter their course to intercept ICARUS 1 and get a second “payload” bomb to help re-boot the sun, thus allowing them two chances for mission success, or do they stay on course and gamble that the one payload they have is enough? It’s not an easy decision. Both choices have consequences. As a reader we want to see what they will do!

The brilliant thing about Sunshine is that each Gap has consequences that lead the characters to a second Gap, and then a third. In Sunshine these Gaps aren’t simple issues of survival. Instead these decisions force the characters to make choices that challenge what it means to be human, how far they are willing to go, and what is an appropriate sacrifice for the greater good. I love the film because it isn’t plot and action for the sake of plot and action. Every action opens a Gap in the character’s world and forces them to react in ways they never thought possible. (Note: I’ve been deliberately vague here, in case you want to watch this movie – which you should!)

I realize both of these examples come from high-stakes adventure stories. Let me give you an example of a Gap that isn’t “life or death” in nature:

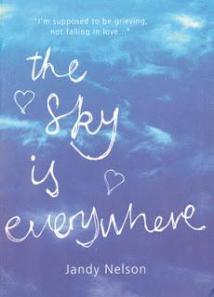

In Jandy Nelson’s young adult novel, The Sky Is Everywhere, teenage protagonist Lennie is dealing with the death of her older sister, Bailey. There’s a wonderful Gap when Lennie is hanging out with her sister’s boyfriend Toby. The two are chatting about Bailey, remembering her, and then they look at each other and — BAM! — Toby kisses Lennie. However, the gap comes in the moment when Lennie realizes she likes kissing her sister’s boyfriend! Suddenly the world has acted in a way outside of all that Lennie thought possible. And even more exciting, now she has to decide what she’s going to do about it.

In Jandy Nelson’s young adult novel, The Sky Is Everywhere, teenage protagonist Lennie is dealing with the death of her older sister, Bailey. There’s a wonderful Gap when Lennie is hanging out with her sister’s boyfriend Toby. The two are chatting about Bailey, remembering her, and then they look at each other and — BAM! — Toby kisses Lennie. However, the gap comes in the moment when Lennie realizes she likes kissing her sister’s boyfriend! Suddenly the world has acted in a way outside of all that Lennie thought possible. And even more exciting, now she has to decide what she’s going to do about it.

So, how can you apply the concept of The Gap to your work?

Ask yourself these questions about your book:

- Within the scope of your story, what Gaps have been presented in your protagonist’s life?

- How is your character challenged and incited to act by those Gaps?

- How has the Gap brought into question what your character believes, wants, and thinks is possible?

- What are the consequences of the choice your character makes when presented with a Gap? Does that choice move the story forward and take your character to the next Gap in the story? If not, does the Gap need to be changed so it challenges your character in stronger way?

- What does your character learn about herself as a result of the choices she makes when presented with those Gaps?

It’s one thing to throw obstacles, problems, and action at your character, but that doesn’t make the story compelling on its own. We often hear the phrase “torture your characters,” but that’s not what captures your reader’s attention. It’s the moral questions imbedded within the choices they must make that allows your reader to peek through the words on the page and see what makes us human. It’s those choices and the subsequent consequences that compel readers to picking the book up, again and again, to see what will happen next.

Want to learn more about The Gap?

Please Read:

- Story by Robert McKee, specifically pages 147 to 149.

- McKee also talks about the Gap on pages: 154-157, 177-180, 208, 270-271, 311-312, 362.

- These page numbers are based on the 1997, hardcover, It Books edition.

Lately I’ve been having a hard time finishing books. Not because the writing is bad, or the stories don’t have developed characters, or even interesting plots. The problem is the stories don’t grip me and I’m not compelled to pick them up again to see what happens next.

With so many distractions in life – television, facebook, cooking classes – it’s easy to put a book down and stop reading. This is a reality we all must face. So, how do we keep our readers hooked? How do we make it impossible for them to put the story down?

Of course there are a lot of possible answers to that question, but the one I want to talk about today is The Gap.

The Gap is a concept coined by Robert McKee in his craft book STORY, wherein he argues that we read because we want to see characters presented with situations that “pry open a gap” in their lives. He describes the Gap as a moment in a character’s life when the world acts in a way that surprises them. It’s a revelation and/or situation in which the character’s landscape operates outside of what they knew was possible.

For example, a tornado headed straight for your character’s house is a gap in their life. Normal life has been interrupted by mother nature and now your character must act. But a gap can also be as small as the “cool kids” deciding to talk to your character at school. It’s any event that tilts your character’s landscape in a new way and presents your character with new opportunities and obstacles. At least, on the surface that’s what a Gap is.

But let’s talk about how to maximize the Gap and make your stories un-put-downable!

McKee describes the Gap this way:

“The protagonist seeks an object of desire beyond his reach. Consciously or unconsciously he chooses to take a particular action, motivated by the thought or feeling that this act will cause the world to react in a way that will be a positive step toward achieving his desire. From his subjective POV the action he has chosen seems minimal, conservative, yet sufficient to effect the reaction he wants. But the moment he takes action, the objective realm of his inner life, personal relationships, or extra-personal world, or a combination of these, react in a way that’s more powerful or different than he expected … his action provokes forces of antagonism that open up the gap between his subjective expectation and the objective result, between what he thought would happen when he took his action and what in fact does happen … The gap is the point where the subjective and objective realms collide, the difference between anticipation and result, between the world as the character perceived it before acting and the truth he discovers in action.” (McKee, Story)

“The protagonist seeks an object of desire beyond his reach. Consciously or unconsciously he chooses to take a particular action, motivated by the thought or feeling that this act will cause the world to react in a way that will be a positive step toward achieving his desire. From his subjective POV the action he has chosen seems minimal, conservative, yet sufficient to effect the reaction he wants. But the moment he takes action, the objective realm of his inner life, personal relationships, or extra-personal world, or a combination of these, react in a way that’s more powerful or different than he expected … his action provokes forces of antagonism that open up the gap between his subjective expectation and the objective result, between what he thought would happen when he took his action and what in fact does happen … The gap is the point where the subjective and objective realms collide, the difference between anticipation and result, between the world as the character perceived it before acting and the truth he discovers in action.” (McKee, Story)

Creating a Gap for your characters isn’t as simple as throwing obstacles in the character’s way and hoping for drama. A compelling Gap will present your character with a situation that demands they make a difficult choice. This choice should be one that isn’t easy to run away from. I should “trap” your character and not allow them to return to their normal way of life. This is the space in which characters grow. It’s the space in which plot becomes so intoxicating your reader cannot put the book down.

Why? Because we want to see what choice the character will make. And, we want to see the consequences of their actions.

McKee goes on to say that:

“Once the gap in reality splits open, the character, being willful and having capacity, senses or realizes that he cannot get what he wants in a minimal, conservative way. He must gather himself and struggle through the gap to take a second action. This next action is something the character would not have wanted to do in the first case because it not only demands more willpower and forces him to dig more deeply into his human capacity, but most important the second action puts him at risk. He now stands to lose in order to gain.” (McKee, Story)

Okay, let’s look at an example to help illustrate this idea.

One of my favorite examples of a compelling Gap is in the reaping scene in The Hunger Games. As writers we have a lot of choices to make in our novels. Hunger Games author, Susan Collins, could have chosen to have Katniss’s name pulled out of the reaping basket. This would have presented a Gap in Katniss’s life. She would be presented with the choice of accepting the challenge of the games or running away and putting her family in danger. But Susan Collins makes the Gap even more intense and unimaginable for Katniss. Instead of pulling Katniss’s name from the reaping basket, her sister Primm’s name is pulled. Now the world has really opened up and torn a Gap in Katniss’s life. The world has truly acted in a way she did not see coming.

The Gap forces Katniss to choose between staying alive and watching her sister go off to die, or choosing to volunteer in her sister’s place and fight to the death. Neither decision is a good one. If you were forced to put the book down at that moment, before Katniss made her decision, don’t you think you would be itching to get back to reading? YES! Of course you want to see what choice she will make. This is the stuff of great drama!

Another great example of Gaps is the movie Sunshine. This is a lesser known sci-fi film directed by Danny Boyle and written by Alex Garland. Every action, decision, and plot point in this movie has a consequence that forces the characters to face a new Gap. The film follows the crew of ICARUS 2, a spaceship flying toward Earth’s dying sun in hopes of “rebooting” it with a nuclear bomb. ICARUS 1 failed its mission in the past and ICARUS 2 is Earth’s last and final hope before the planet dies from lack of sunshine. The first gap in the film comes when ICARUS 2 receives a distress signal from ICARUS 1. The crew is now forced to make a choice. Do they alter their course to intercept ICARUS 1 and get a second “payload” bomb to help re-boot the sun, thus allowing them two chances for mission success, or do they stay on course and gamble that the one payload they have is enough? It’s not an easy decision. Both choices have consequences. As a reader we want to see what they will do!

Another great example of Gaps is the movie Sunshine. This is a lesser known sci-fi film directed by Danny Boyle and written by Alex Garland. Every action, decision, and plot point in this movie has a consequence that forces the characters to face a new Gap. The film follows the crew of ICARUS 2, a spaceship flying toward Earth’s dying sun in hopes of “rebooting” it with a nuclear bomb. ICARUS 1 failed its mission in the past and ICARUS 2 is Earth’s last and final hope before the planet dies from lack of sunshine. The first gap in the film comes when ICARUS 2 receives a distress signal from ICARUS 1. The crew is now forced to make a choice. Do they alter their course to intercept ICARUS 1 and get a second “payload” bomb to help re-boot the sun, thus allowing them two chances for mission success, or do they stay on course and gamble that the one payload they have is enough? It’s not an easy decision. Both choices have consequences. As a reader we want to see what they will do!

The brilliant thing about Sunshine is that each Gap has consequences that lead the characters to a second Gap, and then a third. In Sunshine these Gaps aren’t simple issues of survival. Instead these decisions force the characters to make choices that challenge what it means to be human, how far they are willing to go, and what is an appropriate sacrifice for the greater good. I love the film because it isn’t plot and action for the sake of plot and action. Every action opens a Gap in the character’s world and forces them to react in ways they never thought possible. (Note: I’ve been deliberately vague here, in case you want to watch this movie – which you should!)

I realize both of these examples come from high-stakes adventure stories. Let me give you an example of a Gap that isn’t “life or death” in nature:

In Jandy Nelson’s young adult novel, The Sky Is Everywhere, teenage protagonist Lennie is dealing with the death of her older sister, Bailey. There’s a wonderful Gap when Lennie is hanging out with her sister’s boyfriend Toby. The two are chatting about Bailey, remembering her, and then they look at each other and — BAM! — Toby kisses Lennie. However, the gap comes in the moment when Lennie realizes she likes kissing her sister’s boyfriend! Suddenly the world has acted in a way outside of all that Lennie thought possible. And even more exciting, now she has to decide what she’s going to do about it.

In Jandy Nelson’s young adult novel, The Sky Is Everywhere, teenage protagonist Lennie is dealing with the death of her older sister, Bailey. There’s a wonderful Gap when Lennie is hanging out with her sister’s boyfriend Toby. The two are chatting about Bailey, remembering her, and then they look at each other and — BAM! — Toby kisses Lennie. However, the gap comes in the moment when Lennie realizes she likes kissing her sister’s boyfriend! Suddenly the world has acted in a way outside of all that Lennie thought possible. And even more exciting, now she has to decide what she’s going to do about it.

So, how can you apply the concept of The Gap to your work?

Ask yourself these questions about your book:

- Within the scope of your story, what Gaps have been presented in your protagonist’s life?

- How is your character challenged and incited to act by those Gaps?

- How has the Gap brought into question what your character believes, wants, and thinks is possible?

- What are the consequences of the choice your character makes when presented with a Gap? Does that choice move the story forward and take your character to the next Gap in the story? If not, does the Gap need to be changed so it challenges your character in stronger way?

- What does your character learn about herself as a result of the choices she makes when presented with those Gaps?

It’s one thing to throw obstacles, problems, and action at your character, but that doesn’t make the story compelling on its own. We often hear the phrase “torture your characters,” but that’s not what captures your reader’s attention. It’s the moral questions imbedded within the choices they must make that allows your reader to peek through the words on the page and see what makes us human. It’s those choices and the subsequent consequences that compel readers to picking the book up, again and again, to see what will happen next.

Want to learn more about The Gap?

Please Read:

- Story by Robert McKee, specifically pages 147 to 149.

- McKee also talks about the Gap on pages: 154-157, 177-180, 208, 270-271, 311-312, 362.

- These page numbers are based on the 1997, hardcover, It Books edition.

Wired has a great interview with Joss Whedon. It's very long, but a great read if you're a fan of his, or interested in his thoughts on writing, characters, and plot. Here's the part that I want to talk about though, it's about characters and their motivations:

"...everybody is here for a reason and they deserve, while they’re on film, or on the page, for people to know what it is, even if we don’t like it."Reading this made me feel good because it's something I've always tried to do with both my characters and my plot. I think it's important that in any scene you write, you should be able to turn to each character there and ask "Why are you here?" and they should have an answer. Whether the reason is personal, "I'm here because I love him." or not, "This is my English class, I have to be here." they should be there for some reason that has to do with THEM, and not your plot. If I ask and my character answers, "I'm here because you need me to overhear this argument so that later I can use that info to solve the mystery." then, in my opinion, I've failed to make him three-dimensional, he's merely a plot device in the shape of a person.

Every character, whether they're the main character or one who pops in for one scene, should have a full life, regardless of how much we see of it. When people appear only to prove a point, or drop a clue, or to tell us something about the main character, the whole world of your story feels a little less real.

Achieving this can be tricky. You don't want a minor character to walk into a scene and say, "I'm here because this is my English class, where I'm supposed to be, and I just noticed that your hair looks different." Subtlety is key. This is one of those things where the reason doesn't always have to be spelled out on the page, but YOU need to know it. When you know why a character is there, it shows in your writing, and scenes feel more real.

When it comes to plot points, I always check that all the characters involved are there for a reason, and not because I NEED them to be there in order for the story to move forward. Without that reason -- personal or practical, things can feel "too convenient" or false. You want those moments to feel inevitable, where your readers can almost see it coming, as they weave all the pieces together, and they think, oh no!, at the same time that they think, of course they would all end up in this place just as the bomb goes off, it couldn't be any other way.

Because that's the moment that really connects with the reader. That's where the emotional connection to the story comes in. When they can look back at everything each character has done, and know that this is exactly the way it has to be, because they understand why each character has done what they've done so far, and why they're there at that moment. Without that it's just another thing moving the plot along.

To the right of this post is a list of the 22 Steps in the Plot Series: How do I Plot a Novel, Memoir and Screenplay? (a few more coming soon complete the series)

To the right of this post is a list of the 22 Steps in the Plot Series: How do I Plot a Novel, Memoir and Screenplay? (a few more coming soon complete the series)

Now that I posted the directory of the YouTube series, I wish I started the list with the last one and encourage you work your way forward. Perhaps this will work as a strategy for the writer who never reaches the end, finishes, accomplishes her goals. Perhaps beginning at the end will help you stay true to the cause of writing your story.

Whether by conventional means and you begin at Step One or the unconventional way of beginning at Step 22, my intention is to provide you with a series of videos to guide you step-by-step through the plot elements that create a pleasing form, one that mirrors the universal story.

Benefits of watching the

Plot Series:

1) Become a better writer

Great post, thanks! I read Story a long time ago. I don’t remember the part about The Gap. I guess that means it’s time to read it again.

Thank you! You have saved my book.

I knew that I needed to ramp things up, but I wanted it to be relevant and meaningful.

I just wasn’t certain how to choose the escalation.

After I read your article, I knew immediately what I needed to do.

Thank you very, very much!

Kathy

Kathy! That’s fantastic. I love it when I have ah-ha moments like this!

I’ve been thinking about this in terms of the curiosity gap. You make the reader realize that they don’t know something, like how the character is going to react or get through the situation they’re in. The missing knowledge can even be something like not knowing what another character is thinking, as long as it doesn’t cross the line into being confusing.

LOL Sorry, following my train of thought there.

I love your train of thought MJ! Yes, sometimes the revelation is for the reader! And other times the revelation is for both the reader and the character. It all depends on the story situation and which is more appropriate.

[…] not going to say anything else about that because Ingrid does a fabulous job sharing Robert McKee’s […]

Hey Ingrid, I think I slightly disagree with you on your interpretation of the Gap. My understanding is that it isn’t so much what we throw at our characters. (If that’s what you’re saying.) Instead, when our character moves forward towards their ultimate desire/want (takes action, makes a decision) it’s the space between what they think will happen and what actually occurs. It’s that space (or gap) that keeps them from reaching their desire and forces them to up the ante to get what they want. Ex: my character is the understudy for the lead in the play. She hears that a big agent is going to be at the show. She puts laxatives in the lead’s drink to get her out of the way. The lead gets so sick though, that the play is canceled and my character doesn’t get on stage the way she planned. The Gap is between what she hoped would happen, she would get her big shot at acting… and what does happen, she’s stuck with no play at all. Now she has to still find a way to get noticed and she is a possible suspect for the laxatives. Maybe we are saying the same thing though. No?