new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: NGOs, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 7 of 7

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: NGOs in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Yasmin Coonjah,

on 9/13/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

Politics,

shipwreck,

globalization,

Amnesty International,

Greenpeace,

Social Sciences,

oecd,

*Featured,

NGOs,

A New History of Transnational Civil Society,

Auguste Godde,

International Shipwreck Society,

non governmental organisation,

Sebastian Palet,

The International,

transnational organizations,

Add a tag

The contemporary world features more than twenty thousand international NGOs in almost every field of human activity, including humanitarian assistance, environmental protection, human rights promotion, and technical standardization, amongst numerous other issues

The post A cautionary tale from the history of NGOs appeared first on OUPblog.

By: John Priest,

on 5/26/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Philosophy,

Iraq,

middle east,

human rights,

sexual abuse,

violence,

IS,

morality,

ISIS,

moral philosophy,

*Featured,

human rights abuse,

sharia,

NGOs,

Arts & Humanities,

Yazidi,

Daesh,

absuse,

Diana Tietjens Meyers,

Victims' Stories,

Victims' Stories and the Advancement of Human Rights,

Books,

ethics,

Add a tag

Mass sexual violence against women and girls is a constant in human history. One of these atrocities erupted in August 2014 in ISIS-occupied territory and persists to this day. Mainly targeting women and girls from the Yazidi religious minority, ISIS officially reinstituted sexual slavery.

The post Caring about human rights: the case of ISIS and Yazidi women appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kathleen Sargeant,

on 4/26/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Law,

Journals,

immigration,

Media,

social media,

human rights,

new media,

asylum seekers,

ACCORD,

*Featured,

oxford journals,

arab spring,

NGOs,

refugee status,

International Journal of Refugee Law,

Austrian Centre for Country of Origin Information,

E-evidence,

EASO,

European Asylum Support Office,

Guy Goodwin-Gil,

human rights documentation,

human rights reporting,

human rights violations,

IJRL,

international human rights community,

Jane McAdam,

new technologies,

refugee status determination,

Rosemary Byrne,

RSD,

UNHCR Refworld,

Add a tag

Information now moves at a much greater speed than migrants. In earlier eras, the arrival of refugees in flight was often the first indication that grave human rights abuses were underway in distant parts of the world.

The post Why hasn’t the rise of new media transformed refugee status determination? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Amelia Carruthers,

on 8/18/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

safety,

ethics,

Law,

china,

Politics,

India,

slavery,

regulation,

society,

manufacturing,

*Featured,

Bangladesh,

NGOs,

commercial law,

environmental law,

David Snyder,

Fair Trade Fashion,

International Transactions,

Labour Law,

Add a tag

Fire and collapse in Bangladeshi factories are no longer unexpected news, and sweatshop scandals are too familiar. Conflicting moral, legal, and political claims abound. But there have been positives, and promises of more. The best hope for progress may be in the power of individual contracts.

The post The new social contracts appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 5/28/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Economics,

ideas,

Current Affairs,

experience,

currie,

millennium development goals,

*Featured,

Business & Economics,

dfid,

tearing,

NGOs,

Bruce Currie-Alder,

Common problems,

development studies,

Foreign problems,

International Development,

Prospects,

Sovereign problems,

alder,

development”,

development’,

Add a tag

By Bruce Currie-Alder

Is thinking on international development pulling itself together or tearing itself apart? The phrase ‘international development’ can be problematic, embracing multiple meanings to those inside the business, but often meaningless to those outside of it.

On the surface, the Millennium Development Goals and debates towards a post-2015 agenda imply a move towards consensus. The past 60 years saw the development agenda embrace political independence, economic growth, human needs, sustainability, poverty reduction, and human capabilities. Each represented a particular understanding of what constitutes “development” and how to achieve it. Once dominated by economics and political science, the ideas and concepts used to explain development now draw on insights from across the natural and social sciences. Beyond academic debate, such ideas motivate real-life organizations and practitioners and shape their actions.

A female doctor with the International Medical Corps examines a woman patient at a mobile health clinic in Pakistan. Photo by DFID/Russell Watkins; UK Department for International Development. CC BY 2.0 via DFID Flickr

After interacting with over 90 writers over three years, I am convinced that thinking on development is tearing apart. Contemporary thinking comes from an increasingly diverse set of locations, with Beijing, New Delhi, and Rio de Janeiro challenging and enriching the ideas emanating from London, New York, and Paris. The rise of regional powers and localized approaches to development are reshaping our understanding of how human societies change over time. Fundamentally, the policy space for “international development” is tearing into three separate dialogues.

Sovereign problems concern the use of national wealth. All polities face real constraints in public finance and our societies face analogous challenges, such as: expanding access to and improving the quality of education and health, designing social protection to ensure a minimum wellbeing for everyone, or encouraging opportunities for entrepreneurs and minorities. Dialogue and action on sovereign problems involve national treasuries, political parties, and (mis)informed citizens. One can be inspired by experience abroad, but solutions must be tailored to fit within local cultural, political, and economic reality. This aspect of international development is growing.

Common problems concern international public goods. A sizable portion of our problems spill across borders and potential solutions require cooperation among different polities. Climate change, emergent diseases, and trade regimes surpass the ability of any one country and are affected by the choices made by others (indeed the nation-state is seldom the most useful unit of analysis). Common problems involve separate actors, ranging from municipalities and hospitals, to trade negotiators and the alphabet soup of international forums (IPCC, WHO, IFIs). After the rise of globalization, this aspect of international development is holding steady given the reality of a multi-polar world.

Foreign problems concern how to respond to troubled places abroad. Six decades of development saw substantial increases in life expectancy, human rights, and literacy. Yet there remains a stubborn set of poverty hotspots, ungoverned spaces, and fragile states where life continues to be nasty, brutish, and short. Dialogue and action involve foreign ministries, aid agencies, and NGOs. There are encouraging signs that this aspect of international development is in decline. The long-term trend witnessed a decrease in inter-state conflict and a dwindling list of low-income countries reliant on foreign aid. As such, the agenda is narrowing towards humanitarian relief, rural development, and state-building in remote locations.

This triad of sovereign-common-foreign offers one potential typology for the future evolution of thinking currently gathered under “international development”. Put more simply, when world leaders meet, the problems they discuss fit into the categories of mine-ours-theirs: those involving dialogue at home, those that require coordinated action across borders, and those related to hotspots beyond our borders.

In short, the label of “international development” has outlived its usefulness and is tearing apart in both academics and practice. For example, in the United Kingdom there is a tension between “development studies” focused on low-and-middle income countries, and “development sciences” applying technology to the needs of the poor. Meanwhile the range of organizations that engage in development has expanded, diversified, and coalesced into specialized communities. Once the exclusive purview of aid agencies and international organizations, there is an increasingly role for national treasuries, domestic charities, and diasporas in addressing different problems.

Looking forward, it seems likely that what is described as “international development” is destined to become a historic juncture, describing a period when we jumbled things together differently.

Bruce Currie-Alder is Regional Director, based in Cairo, with Canada’s International Development Research Centre (IDRC). He is an expert in natural resource management, and on the policies that govern public research funding and scientific cooperation with developing countries. His previous experience includes facilitating corporate strategy, contributing to Canada’s foreign policy, and work in the Mexican oil industry. He co-edited International Development: Ideas, Experience and Prospects (Oxford 2014) which traces the evolution of thinking about international development over sixty years. Currie-Alder holds a Master’s in Natural Resource Management from Simon Fraser University and a PhD in Public Policy from Carleton University.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Pulling together or tearing apart appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 3/12/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Law,

democracy,

Politics,

charity,

Current Affairs,

British,

charities,

lobbying,

UK politics,

social history,

trade unions,

*Featured,

campaigners,

NGOs,

matthew hilton,

the politics of expertise,

UK lobbying bill,

UK parliament,

kaihsu,

Add a tag

By Matthew Hilton

On 30 January 2014 the UK government’s lobbying bill received the Royal Assent. Know more formally known as the Transparency of Lobbying, Non-Party Campaigning and Trade Union Administration Act, it seeks to curb the excesses in election campaign expenditure, as well as restricting the influence of the trade unions.

However, as various groups pointed out throughout its controversial parliamentary journey, Part 2 of the legislation will also have implications for charities, voluntary societies and non-governmental organisations once it comes into effect. Specifically, in restricting the amount of expenditure that non-party political bodies can spend ahead of a general election, it will severely curtail their lobbying, campaigning and advocacy work that has been a standard feature of their activities for some decades.

Understandably the sector has not welcomed the Act. The problem is that the legislation conflates general political lobbying with campaigning for a specific cause that is central to the charitable mission of an organisation. Sector leaders have critiqued the Bill as ‘awful’, ‘an absolute mess’ and ‘a real threat to democracy’.

It is not difficult to see why. The impact of charities on legislation in Britain has been profound and the examples run into many hundreds of specific Acts of Parliament. To mention but a few, a whole range of environmental groups successfully lobbied for the Climate Change Act 2008. Homelessness charities such as Shelter and the Child Poverty Action Group fought a battle for many years that resulted in the Housing Act 1977. The 1969 abolition of the death penalty can be partly attributed to the National Campaign for the Abolition of Capital Punishment and two pieces of legislation in 1967, the Sexual Offences Act and the Abortion Act, were very much influenced by the work of the Homosexual Law Reform Society and the Abortion Law Reform Association.

The list could run on and on, but the impact of advocacy by charities on the policy process has become far more extensive than the straightforward lobbying of MPs. Charities have been key witnesses in Royal Commissions, for instance. From the 1944 Commission on Equal Pay Act through to the 1993 Commission on Criminal Justice, voluntary organisations contributed over a 1,000 written submissions. At Whitehall, they have sought a continued presence along the corridors of power in much the same manner as commercial lobbying firms. They have achieved much through the often hidden and usually imprecise, unquantifiable and unknowable interpersonal relationships fostered with key civil servants, both senior and junior.

In more recent years, charities have taken advantage of early day motions in the House of Commons. Once infrequently employed, by the first decade of the 21st century, there were on average 1,875 early day motions in each parliamentary session. The most notable have managed to secure over 300 signatures and it is here that the influence of charities is particularly apparent. The topics that obtain such general — and cross-party — support have tended to be in the fields of disability, drugs, rights, public health, the environment, and road safety; all subjects on which charities have been particularly effective campaigners.

Not all of these lobbying activities have been successful. Leaders of charities have often expressed their frustration at being unable to influence politicians who refuse to listen, else being outgunned and out-voiced by lobbyists with greater financial muscle supporting their work. But the important point is that charities have had to engage in the political arena and it is the norm for them to do so. To restrict these activities now — even if only in the year in the run-up to a general election — actually serves to turn back a dominant trend in democratic participation that has come increasingly to the fore in contemporary Britain.

Having explored the history of charities, voluntary organisations and NGOs, tracing their growing power, influence and support, we found was that rather than there having been a decline in democracy over the last few decades there has actually been substantial shifts in how politics takes place. While trade unions, political parties and traditional forms of association life have witnessed varying rates of decline, support for environmental groups, humanitarian agencies and a whole range of single-issue campaigning groups has actually increased. Whether these groups represent a better or worse form of political engagement is not really the issue. The point is that the public has chosen to support charities — and charitable activity in the political realm — because ordinary citizens have felt these organisations are better placed to articulate their concerns, interests and values. As such, charities, often working at the frontier of social and political reform, but often alongside governments and the public sector, have become a crucial feature of modern liberal democracy.

One might have expected a government supposedly eager to embrace the ‘Big Society’ particular keen to free these organisations from the bureaucracy of the modern state. But it is quite clear that the Coalition has held a highly skewed, and rather old fashioned, view of appropriate charitable activity. The Conservatives imagined a world of geographically-specific, community self-help groups that might pick up litter on the roadside in their spare time at the weekend and who would never imagine that their role might be, for instance, to demand that local government obtains sufficient resources to ensure that the public sector — acting on the behalf of all citizens and not just a select few — would continue to maintain and beautify the world around us. There are clearly very different views on what charity is and what it should do.

Indeed, it is remarkable that when government spokespeople did comment on the nature of the charitable sector, they were quick to condemn the work of the bigger organisations. Lord Wei, the ‘Big Society tsar’, even went so far as to criticise the larger charities for being ‘bureaucratic and unresponsive to citizens’. With such attitudes it is no wonder the Big Society soon lost any pretence of adherence from the many thousands of bodies connected to the National Council of Voluntary Organisation.

It is tempting to see the particular form the Conservatives hoped the Big Society would take as part and parcel of a policy agenda that is connected to the lobbying bill. That is, there has never been an embrace of charities by Cameron and his ministers as the solution to society’s – and the state’s – ills. Rather, in viewing these developments alongside the huge cuts in public sector funding (which often trickled down to national and community-based charities), there has actually been a sustained attack on the very nature of charity, or at least it has developed as a sector in recent decades. It is no wonder that many charity leaders and CEOs, feeling cut off at the knees by the slashes to their budgets and damaged by the sustained abuse in the press for their mistakenly inflated salaries, now feel the Lobbying Act is seeking to gag their voice as well.

Matthew Hilton is Professor of Social History at the University of Birmingham, and the author of The Politics of Expertise: How NGOs Shaped Modern Britain, along with James McKay, Nicholas Crowson and Jean-François Mouhot. Together they also compiled ‘A Historical Guide to NGOs in Britain: Charities, Civil Society and the Voluntary Sector since 1945′ (Palgrave, 2012). All the data contained in these two volumes, as well as that found above, is freely available on their project website.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Why the lobbying bill is a threat to the meaning of charity appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 1/23/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Current Affairs,

Nicaragua,

walmart,

farmers,

supermarket,

supermarkets,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Business & Economics,

American Journal of Agricultural Economics,

Hope Michelson,

NGOs,

small farmer,

Add a tag

By Hope Michelson

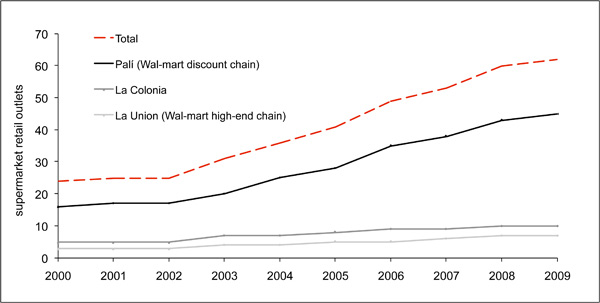

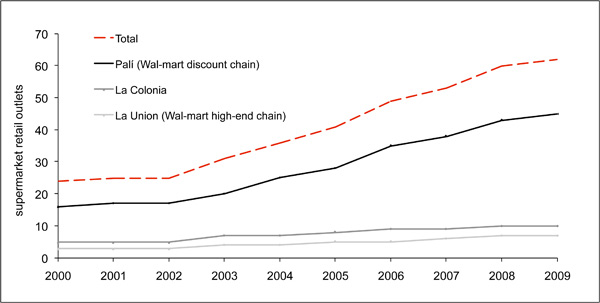

Walmart now has stores in more than fifteen developing countries in Central and South America, Asia and Africa. A glimpse at the scale of operations: Nicaragua, with a population of approximately six million, currently has 78 Walmart retail outlets with more on the way. That’s one store for every 75,000 Nicaraguans; in the United States there’s a Walmart store for every 69,000 people. The growth has been rapid; in the last seven years, the corporation has more than doubled the number of stores in Nicaragua (see accompanying graphs — Figure 1 from the paper).

When a supermarket chain like Walmart moves into a developing country it requires a steady supply of fresh fruits and vegetables largely sourced domestically. In developing countries where the majority of the poor rely on agriculture for their livelihood, this means that poor farmers are increasingly selling produce to and contracting directly with large corporations. In precisely this way, Walmart has begun to transform the domestic agricultural markets in Nicaragua over the past decade. This profound change has been met with both excitement and trepidation by governments and development organizations because the likely effects on poverty and inequality are not known, in particular:

- What existing assets or experience are required for a farmer to sell their produce to supermarkets?

- Do small farmers who sell their produce to supermarkets benefit from the relationship?

- What is the role of NGOs in facilitating small farmer relationships with supermarkets?

Supermarkets require that farmers meet standards related to production, post-harvest processing, and delivery; for example, the use of specific pesticides and fertilizers and the cleaning and packaging of vegetables. Moreover, supermarkets generally require farmers to guarantee production year round, which requires planning (sometimes across multiple farmers), irrigation and capital. These requirements can present significant challenges to small farmers with little capital and it is thought that such challenges could strongly effect which farmers sell produce to supermarkets.

Supermarkets require that farmers meet standards related to production, post-harvest processing, and delivery; for example, the use of specific pesticides and fertilizers and the cleaning and packaging of vegetables. Moreover, supermarkets generally require farmers to guarantee production year round, which requires planning (sometimes across multiple farmers), irrigation and capital. These requirements can present significant challenges to small farmers with little capital and it is thought that such challenges could strongly effect which farmers sell produce to supermarkets.

Generally, researchers have studied the inclusion of farmers in supply chains by measuring the income, assets and welfare of a group of farmers selling a crop to supermarkets (“suppliers”) with a similar group of farmers selling the same crop in traditional markets (“non-suppliers”). This research has provided important insights but has struggled with two persistent challenges.

First, because most existing studies rely on surveys of farmers living in the same area, we do not know how important farmer experience or assets such as farm machinery or irrigation, are for inclusion in supply chains in comparison to other farmer characteristics like community access to water or proximity to good roads.

Second, without measurements on supplier and non-supplier farmers over time it is difficult for a researcher to isolate the effect being a supplier has on the farmer. For example, if Walmart excels at choosing higher-ability farmers as suppliers, a study that just compared supplier and non-supplier incomes would overestimate the supermarket effect because Walmart’s high-ability farmers would earn more income even if they had not contracted with the supermarket.

With these two challenges in mind, I implemented a research project in Nicaragua in which I first identified all small farmers who had had a steady supply relationship with supermarkets for at least one year since 2000 (see accompanying graphs — Figure 2 from the paper). I also revisited 400 farmers not supplying supermarkets but living in areas where supermarkets were buying produce. My team and I surveyed farmers about their experiences over the past eight years: the markets where they had sold, the farming, land, and household assets they had owned. Since my study included farmers selling a variety of crops to supermarkets and measured how their assets, and supermarket relationships, changed in time, I was able to more rigorously address how these markets affected small farmers. The project was part of a collaboration between researchers Michigan State University, Cornell University, and the Nitlapan Institute in Managua.

Results

Farmer participation

Farmers located close to the primary road network and Nicaragua’s capital, Managua, where the major sorting and packing facility is located, and with conditions that allow them to farm year round were much more likely to be suppliers. Remarkably, this effect was much stronger than other farmer characteristics such as existing farm capital or experience.

Farmer welfare

Suppliers do benefit from selling their produce to supermarkets. The assets of farmers that sold to supermarkets for at least one year between 2000 and 2008 were 16% higher than for farmers that did not sell to supermarkets.

Suppliers do benefit from selling their produce to supermarkets. The assets of farmers that sold to supermarkets for at least one year between 2000 and 2008 were 16% higher than for farmers that did not sell to supermarkets.

One way to think of income is as a flow of financial resources based, in part, on a farmer’s assets. By statistically relating a change in assets to a change in income I find that a 16% increase in assets corresponds to an average increase in annual household income of about $200 — or 15% of the average 2007 income for the farmers I studied.

Our previous work discovered that supermarkets don’t pay farmers a higher mean price than traditional markets but they do offer a more stable price. This analysis suggests a reason that household assets – and thus income — increase among farmers who sell to supermarkets; shielded from price fluctuations in the traditional markets by the supermarket contract, farmers invest in agriculture, in some cases moving to year-round cultivation. Farmers finance these investments through higher and more stable incomes and new credit sources. Income increases are attributable not to higher average prices but likely to increased production quantities.

NGOs

NGOs have played an important role in small farmer access to supermarket supply chains all over the world. In Nicaragua, a USAID program funded NGOs to help small farmers sell to supermarkets. These NGOs established farmers’ cooperatives and provided technical assistance, contract negotiation, and financing. Do NGOs change farmer selection or outcomes? Do they choose farmers with less wealth or experience? Or do farmers working with NGOs benefit in a special way from supermarkets because of the services NGOs provide?

We find, on average, that NGO-assisted farmers start with similar productive assets and land as those who sell to supermarkets without NGO assistance. Nor do we find a special effect on the assets of NGO-assisted farmers. However, we do find that NGOs play a critical role in keeping farmers with little previous experience in vegetable production in the supply chain. Low-experience farmers who are not assisted by NGOs are more likely to drop out of the supply chain than those assisted by NGOs.

Conclusions

These findings offer grounds for optimism and also a measure of caution with respect to the effects of supermarkets operating in developing countries. Supermarket contracts improve farmer welfare, and the improvements are detectable in farmers’ assets. However, since being close to roads and having the ability to farm year round is so critical to inclusion in the supply chain, not all farmers will be afforded these opportunities. Moreover, because these trends are still nascent in Nicaragua and in many other parts of the developing world, it remains to be seen what the broader effects will be for the agricultural sector and development. For example, as NGOs invest in preparing more small farmers to supply supermarkets, the gains to farmers from joining supply chains may be lost to increased competition. Our results in Nicaragua suggest that, given the small number of supplier farmers, changes in rural poverty related to supermarket expansion will be modest, but how will these supply chains, and the benefits they represent for farmers, change over time? I am currently a part of a team studying Walmart supply chains in China, which will interrogate these questions on a much larger scale in the context of a global and rapidly expanding economy.

Hope Michelson is a postdoctoral fellow at Columbia University’s Earth Institute in the Tropical Agriculture and Rural Environment program. She completed her doctoral research in the Economics of Development in 2010 at Cornell University’s Department of Applied Economics. She is the author of “Small Farmers, NGOs, and a Walmart World: Welfare Effects of Supermarkets Operating in Nicaragua” in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics, which is available to read for free for a limited time.

The American Journal of Agricultural Economics provides a forum for creative and scholarly work on the economics of agriculture and food, natural resources and the environment, and rural and community development throughout the world.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: All images property of Hope Michelson. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post What happens when Walmart comes to Nicaragua? appeared first on OUPblog.

Supermarkets require that farmers meet standards related to production, post-harvest processing, and delivery; for example, the use of specific pesticides and fertilizers and the cleaning and packaging of vegetables. Moreover, supermarkets generally require farmers to guarantee production year round, which requires planning (sometimes across multiple farmers), irrigation and capital. These requirements can present significant challenges to small farmers with little capital and it is thought that such challenges could strongly effect which farmers sell produce to supermarkets.

Supermarkets require that farmers meet standards related to production, post-harvest processing, and delivery; for example, the use of specific pesticides and fertilizers and the cleaning and packaging of vegetables. Moreover, supermarkets generally require farmers to guarantee production year round, which requires planning (sometimes across multiple farmers), irrigation and capital. These requirements can present significant challenges to small farmers with little capital and it is thought that such challenges could strongly effect which farmers sell produce to supermarkets. Suppliers do benefit from selling their produce to supermarkets. The assets of farmers that sold to supermarkets for at least one year between 2000 and 2008 were 16% higher than for farmers that did not sell to supermarkets.

Suppliers do benefit from selling their produce to supermarkets. The assets of farmers that sold to supermarkets for at least one year between 2000 and 2008 were 16% higher than for farmers that did not sell to supermarkets.