By Elvin Lim

When a nation chooses to celebrate the date of its birth is a decision of paramount significance. Indeed, it is a decision of unparalleled importance for the world’s “First New Nation,” the United States, because it was the first nation to self-consciously write itself into existence with a written Constitution. But a stubborn fact stands out here. This new nation was created in 1787, and the Fourth of July that Americans celebrate today occurred on a different summer eleven years before.

The united States (capitalization, as can be found in the Declaration of Independence, is advised) declared themselves independent on 4 July 1776, but the nation was not yet to be. An act of severance did not a nation make. These united States would only become the United States when the idea of a collective We the People was negotiated and formally set on parchment in the sweltering summer of 1787. This means that while every American celebrates the revolution against government every July 4th, pro-government liberals do not quite have an equivalent red-letter day to celebrate and to mark the equally auspicious revolution in favor of government that transpired in 1787. Perhaps this is why the United States remains exceptional among all developed countries in her half-hearted attitude toward positive liberty, the welfare state, and government regulation on the one hand, and her seeming addiction to guns, individual rights, and negative liberty, on the other. In part because the nation’s greatest national holiday was selected to commemorate severance and not consolidation, (at least half of) America remains frozen in the euphoric tide of the 1770s rather than the more pragmatic, nation-building impulse of the 1780s.

The Fourth of July was only Act One of the creation of the American republic. In the interim years before the nation’s elders (the imprecise but popular nomenclature is “founders”) came together again—this time not to address the curse of the royal yolk, but to discuss the more mundane post-revolutionary crises of interstate conflict especially in matters of trade and debt repayment—the states came to realize that the threat to liberty comes not always from on high by way of royal governors, but also sideways courtesy of newfound friends. In the mid-1780s, George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and their compatriots came together to design a more perfect union: a union with the power to lay and collect taxes, to raise and support armies, and an executive to wage war. This was Act Two, or the Second American Founding.

Custom and the convenience of having a bank holiday during the summer when the kids are out of school has hidden the reality of the Two Foundings. We now refer to a single founding, and a set of founders, but this does great injustice to the rich experiential tapestry that helped forge the United States. It denies the very substantive philosophic reasons for why one half of America is so convinced that liberty consists in rejecting government, but one half also thinks that flogging that dead horse with the King long slain seems needlessly self-defeating. As Turgot, the Abbé de Mably, put it in a letter to Dr. Richard Price in 1778, “by striving to prevent imaginary dangers, they have created real ones.” To many Europeans, that the citizens of United States have devoted so much energy—waging even a Civil War—against its own central government and fortifying themselves against it indicates a revolutionary nation in arrested development; a self-contradictory denial that the government of We the People is of, by, and for us.

The United States is thoroughly and still vividly ensconced in the original dilemma of civil society today, whether liberty is best achieved with government or without it. Conservatives and liberals are each so sure that they are the true inheritors of the “founding” because they can point to, respectively, the principles of the First and the Second Foundings to corroborate their account of history. And they will continue to do so for as long as the sacred texts of each of the Two Foundings, the Declaration and the Constitution, stand side by side, seemingly at peace with the other, but in effect in mutual tension.

This Fourth of July, Americans should not despair that the country seems so fundamentally divided on issues from healthcare to Iraq. For if to love is divine, to quarrel is American; and we have been having at it for over two centuries.

Elvin Lim is Associate Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and is the author of The Lovers’ Quarrel: The Two Foundings and American Political Development and The Anti-Intellectual Presidency. He blogs at www.elvinlim.com and his column on politics appears on the OUPblog regularly.

Elvin Lim is Associate Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and is the author of The Lovers’ Quarrel: The Two Foundings and American Political Development and The Anti-Intellectual Presidency. He blogs at www.elvinlim.com and his column on politics appears on the OUPblog regularly.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post 1776, the First Founding, and America’s past in the present appeared first on OUPblog.

.

.

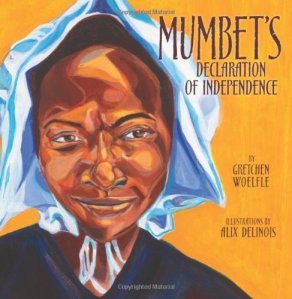

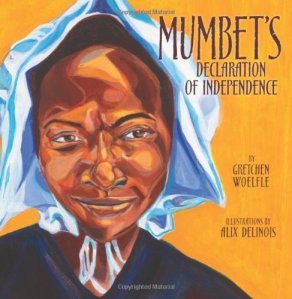

Mumbet’s Declaration of Independence

by Gretchen Woelfle & Alix Delinois, illustrator

Carolrhoda Books 2/01/2014

978-0-7613-6589-1

Age 7 to 9 32 pages

.

“All men are born free and equal.” Everybody knows about the Founding Fathers and the Declaration of Independence in 1776. But the founders weren’t the only ones who believed that everyone had a right to freedom. Mumbet, a Massachusetts slave believed it too. She longed o be free, but how? Would anyone help her in her fight for freedom? Could she win against her owner, the richest man in town? Mumbet was determined to try. Mumbet’s Declaration of Independence tells her story for the first time in a picture book biography, and her brave actions set a milestone on the road toward ending slavery in the United States.”

Opening

“Mumbet didn’t have a last name because she was a slave. She didn’t even have an official first name. Folks called her Bett or Betty. Children called her Mom Bett or Mumbet. Others weren’t so kind.”

The Story

The year is 1776 and the United States begins its fight for freedom from the rule of the British by declaring on paper their Declaration of Independence. Mumbet is a slave owned by the richest man in town—the one who is usually the most powerful in town. Colonel John Ashley lived in Massachusetts and owed many businesses. He might have been kind, but his wife was definitely a cruel woman when it came to her husband’s slaves. Mumbet worked for Mrs. Ashley, usually in her kitchen. Mumbet hated that another human owned her, as wouldn’t you or I. She knew servants and hired hands could leave a cruel employer, but Mumbet had no recourse—she’s is property.

As the founding fathers gathered to write the Declaration of Independence, which started the seven-year war against the British, Mumbet served refreshments and tried to listen. The men were against British taxes and feared losing all their rights under British rule. As Mumbet listened, she heard one man say,

“He [the King of England] would make us slaves.”

And,

“Mankind in a state of Nature are equal, free, and independent . . .

God and Nature have made us free.”

After seven years of war against England, and freedom won, the town held a meeting to introduce The Massachusetts Constitution in 1780. It declared,

“All men are born free and equal.”

Mumbet wondered if that meant her. She approached Theodore Sedgwick, a young lawyer who helped draft the Declaration of Independence, and asked him to represent her in a fight for her personal freedom under the new Massachusetts law. He accepted. Mr. Sedgwick reminded the judge and jury that no law existed in Massachusetts making slaves legal and the new constitution now made them illegal. Would the judge and jury agree with Mr. Sedgwick and grant Mumbet her freedom—and the freedom of all slaves in Massachusetts in the process?

Review

Mumbet’s story, a true story, is an unusual biography in that I don’t recall hearing about this woman in any history class, not even American History. Mumbet had strength unseen except on rare occasions. To take your master to court to demand your freedom was a crazy idea. Even white women were still considered their husband’s chattel, why would a slave be above that. How was Mumbet going to convince a jury—not of her peers—and a judge—most likely friends with the richest man in town—that she deserved her freedoms for the same reason as the men deserved theirs from Britain? The new Massachusetts Constitution was not that old and here is this slave trying to gain her freedom, yet she is property. This must have caused some laughter, smirking, and hate. I find this story truly moving. Her new name became Elizabeth Freeman, a most deserved last name.

Mumbet’s clear and succinctly written story tells of an amazing, intelligent, and courageous woman who dared stand up for her rights when no one ever considered her to have rights. She entered a paternal courtroom, a jury not of her peers, and a town overflowing with curious citizens not all of which could have been happy Mumbet wanted freedom. It was probably more hostile, considering ever man probably stood to lose his slaves if Mumbet were successful. That makes Mumbet one of the strongest woman to have ever lived in the United States.

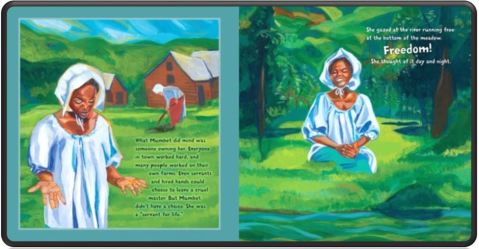

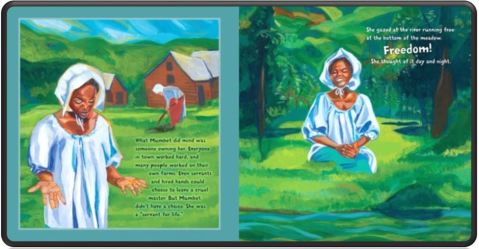

The illustrations are profoundly beautiful with deep rich colors. Even the end pages have an elegance to them. Alix Delinois represented that time in America accurately, with facial expressions that must have matched the frustration felt by most citizens, as the founding fathers wrote the Declaration of Independence. Mrs. Ashley’s cruelty is shockingly visible, immediately making you feel empathy for Mumbet and her daughter. For people sincerely wanting freedom and respect from the British, some were capable of much harm to others.

Thankfully, someone thought to write down Mumbet’s story giving the author great accounts of Mumbet’s life and challenges before, during, and after that day in court. After the story are two pages of author notes. They tell of the help the author received from Catharine Maria Sedgwick, Theodore Sedgwick’s daughter. Catharine wrote Mumbet’s story as it happened, leaving accurate historical documents from which this story was written. These notes are fascinating.Teachers would do well to keep Mumbet’s Declaration of Independence as an adjunct history lesson. It is a story not told in most history classes. Gretchen Woelfle’s impeccable research and storytelling skills gives us a story of slavery not well known in the very country in which it happened—until now. Mumbet’s Declaration of Independence should fascinate kids and adults alike.

MUMBET’S DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE. Text copyright © 2014 by Gretchen Woelfle. Illustrations copyright © 2014 by Alix Delinois. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Carolrhoda Books, Minneapolis, MN.

Buy a copy of Mumbet’s Declaration of Independence at Amazon —B&N—iTunes—Book Depository—Carolrhoda Books—at your local bookstore.

—B&N—iTunes—Book Depository—Carolrhoda Books—at your local bookstore.

.

Learn more about Mumbet’s Declaration of Independence HERE.

Meet the author, Gretchen Woelfle, at her website: http://www.gretchenwoelfle.com/

Meet the illustrator, Alix Delinois, at his website: http://alixdelinois.com/home.html

Find more books a the Carolrhoda Books blog: http://carolrhoda.blogspot.com/

Carolrhoda Books is a division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. https://www.lernerbooks.com/

.

Also by Gretchen Woelfle

Write On, Mercy!: The Secret Life of Mercy Otis Warren

All the World’s a Stage: A Novel in Five Acts

The Wind at Work: An Activity Guide to Windmills

Also by Alix Delinois

Eight Days: A Story of Haiti

Muhammad Ali: The People’s Champion

.

.

Filed under:

6 Stars TOP BOOK,

Children's Books,

Favorites,

Historical Fiction,

Library Donated Books,

NonFiction,

Picture Book,

Top 10 of 2014 Tagged:

1776,

Alix Delinois,

American Revolutionary War,

Carolrhoda Books,

children's book reviews,

Declaration of Independence,

freedom,

Gretchen Woelfle,

Lerner Publishing Group,

Massachusetts Constitution of 1780,

slavery

By Elvin Lim

Yesterday was Independence Day, we correctly note. But most Americans do not merely think of July 4 as a day for celebrating Independence. We are told, especially by the Tea Partying crowd, that we are celebrating the birth of a nation. Not quite.

Independence, the liberation of the 13 original colonies form British rule, did not create a nation any more than a teenager leaving home becomes an adult. Far from it, even the Declaration of Independence (which incidentally, was not signed on July 4, but in August), did not even refer to the “United States” as a proper noun, but instead, registered the “unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America.” And that was all we were in 1776 – a collection of states with no common mission, linked fate, or general government. This was the understanding of the the Franco-American treaties of 1778, which referred to the “United States of North America.”

America was not America until it was, well, constituted. The United States of America was born after the 9th State ratified the US Constitution, and Congress certified the same on September 13, 1788. So we should by all means celebrate the 4th, but confusing Independence with the birth of a nation has serious constitutional-interpretive implications. If the two are the same, then the Declaration’s commitment to negative liberty — freedom from government — gets conflated with the Constitution’s commitment to positive liberty — its charge to the federal government to “secure the Blessings of Liberty.” The fact of the matter is that government was a thing to be feared in 1776. Government, or so the revolutionaries argued, was tyrannical, distant, and brutish. But it was precisely a turnaround in sentiment in the years leading up to 1789 — the decade of confederal republican anarchy — that the States came around to the conclusion that government was not so much to be feared than it was needed. This fundamental reversal of opinion is conveniently elided in Tea-Party characterizations of the American founding.

It is no wonder that politicians can get American history so wrong if we ourselves — 84 percent, according to the National Constitution Center’s poll in 1997 — actually believe that the phrase “all men are created equal” are in the Constitution. Actually, quite the opposite. Those inspirational words in the Declaration of Independence have absolutely zero constitutional weight, and they cannot be adduced as legal arguments in any Court in the nation.

Nations are not built by collective fear. Jealousy is a fine republican sentiment, especially if it is directed against monarchy, but it is surely less of a virtue when directed against a government constituted by We the People unless jealousy against oneself is not a self-defeating thing. What remains a virtuous sentiment, in monarchies or in republics, however, is fellow-feeling, a collective identification with the “general Welfare.” America can move in the direction of “a more perfect Union” only if citizens can come to accept that the Declaration of Independence was the prelude to the major act, and not the culminating act in itself. At the very least, we could get an extra federal holiday in September.

In celebration of the New York Public Library’s centennial festival weekend, game designer Jane McGonigal has crafted the “Find the Future” scavenger hunt.

500 players will join the “Write All Night” event on May 20th. Inside the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, they will use laptops and smartphones to find 100 objects from the library’s collection of treasures and perform a related-writing challenge.

The video embedded above features a promo clip for the event; it seems to mimic The Da Vinci Code‘s film trailer. If you want to participate, just answer this question: “In the year 2021, I will become the first person to __________.” Submit your answer before 11:59 PM Pacific Time on April 21st.

continued…

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

Dennis Baron is Professor of English and Linguistics at the University of Illinois. His book, A Better Pencil: Readers, Writers, and the Digital Revolution, looks at the evolution of communication technology, from pencils to pixels. In this post, also posted on Baron’s personal blog The Web of Language, he explains how digital archaeology has revealed Thomas Jefferson’s revisions of the Declaration of Independence. Read his previous posts here.

Jefferson on the two-dollar bill

In a list of the colonies’ grievances against King George III Jefferson wrote, “he has incited treasonable insurrections of our fellow-subjects, with the allurements of forfeiture and confiscation of our property.” But the future president, whose image now graces the two-dollar bill, must have realized right away that “fellow-subjects” was the language of monarchy, not democracy, because “while the ink was still wet” Jefferson took out “subjects” and put in “citizens.”

In a eureka moment, a document expert at the Library of Congress examining the rough draft late at night suddenly noticed that there seemed to be something written under the word citizens. It was no Da Vinci code or treasure map, but Jefferson’s original wording, soon uncovered using a technique called “hyperspectral imaging,” a kind of digital archeology that lets us view the different layers of a text. The rough draft of the Declaration was digitally photographed using different wavelengths of the visible and invisible spectrum. Comparing and blending the different images revealed the word that Jefferson wrote, then rubbed out and wrote over.

Above: Jefferson’s rough draft reads, “he has incited treasonable insurrections of our fellow-citizens”; followed by a detail of “fellow-citizens” with underwriting visible in ordinary light. Below: a series of hyperspectral images made by the Library of Congress showing that Jefferson’s initial impulse was to write “fellow-subjects.” [Hi-res images of the rough draft are available at the Library of Congress website.] Elsewhere in the draft Jefferson doesn’t hesitate to cross out and squeeze words and even whole lines in as necessary, but in this case he manages to fit his emendation neatly into the same space as the word it replaces.

0 Comments on Revising Our Freedom as of 1/1/1900

Posted on 7/6/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Constitution,

Politics,

Current Events,

American History,

A-Featured,

Glenn Beck,

independence,

Declaration of Independence,

Sean Hannity,

bonfires,

declaration,

July 4,

"John Adams",

negative liberty,

positive liberty,

illuminations,

1780s,

1770s,

1789,

liberties,

Add a tag

Elvin Lim is Assistant Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and author of The Anti-intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com. See Lim’s previous OUPblogs here.

Americans celebrate Independence Day on July 4, the day the words of the Declaration of Independence were set on parchment. John Adams had famously predicted that this day “ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.” Because these celebrations have become annual rituals, we have stopped thinking about exactly what it is we are celebrating.

For a glaring fact stares at us in the face. The Declaration of Independence has absolutely no legal or constitutional status. Presidents and journalists alike appropriate the principles it articulated in their rhetorical flourishes, but for all its symbolic power, the Declaration cannot be quoted by a judge on the Supreme Court to justify an opinion.

A National Day ought to commemorate what it is to be American, and the truth is, the Declaration may well have been the necessary, though certainly not the sufficient part of what made America America. In 1776, the Continental Congress severed our ties to the British crown. That was only a negative act which did not positively define who we were. That positive definition would only come in 1789, when “We the People” would constitute the American nation.

Two hundred years after the fact, Americans commemorate the events of the 1770s and the 1780s as if they were the same decade. But (in order to understand the strive in our contemporary politics) it is important to recall that the 1770s (and the Declaration) and the 1780s (and the Constitution) represented two opposite world-views. The revolutionary generation and the Founding generation were not always on the same page.

The Declaration, ultimately, was an act to guarantee our negative liberties. (Independence = freedom from.) It was a revolutionary act by “one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another.” The revolutionary generation thought, contrary to what most modern liberals believe, that government was evil. The less of it we had to endure, the better.

The Constitution, in contrast, was an act to guarantee our positive liberties or our freedom to do certain things. The American People came together “in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity.” The Founding generation, chastened by the inadequacies of the Continental Congress, came to see government in more benign terms. Contrary to Glenn Beck, 1789 was the culmination of a collective call for more government, not less. By 1789, memories of government as a source of evil had receded into the background, while promises of government as a force to do good hovered in the foreground.

The Declaration and Constitution are not of a piece, but are in fact the book-ends of the American ideological spectrum, presenting two competing visions of government; whether it is the so

I've posted several times in the past on picture books about the American Revolution (Selene Castrovilla's

By the Sword and Upon Secrecy, Anne Rockwell's

They Called Her Molly Pitcher, and several versions of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's

The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere). And yet, I continue to get requests for more!

New Jersey teachers, especially, have a keen interest in this topic, and not just because it's required in the Core Content Curriculum standards. New Jersey is known as the Garden State, but ask any 4th grader in the state for a second claim to fame, and they'll tell you that New Jersey is also called

The Crossroads of the Revolution. Situated between the strategic colonial cities of New York and Philadelphia, New Jersey witnessed over 100 battles during the War for Independence, as many battles as all other colonies combined.

Lynne Cheney's

When Washington Crossed the Delaware: A Wintertime Story for Young Patriots tells how an event in Trenton, New Jersey would later be called a turning point in the War for Independenc. Readers are provided just enough historical context to set the scene for Washington’s bold attack on Trenton. With his army depleted to just ten percent of its original strength and half his troops’ enlistments about to expire, General George Washington is desperate for a victory. The hope of the new nation rests upon an impossible winter attack on an intimidating foe who has already crushed the Americans in New York and chased them across New Jersey and the Delaware River itself. The rich text and saturated illustrations recount the battles of Trenton as well as Princeton, and accurately depict the resounding effect that these two victories had upon the morale of the Continental Army. Cheney's book is filled not only with beautiful illustrations, but also with numerous quotations from those who lived the events described within the book's covers.

A great extension for this book? Let students pretend that they're colonial soldiers under Washington's command and have them write letters "home" explaining why they're continuing to fight. (An interesting note: following the Batlle of Trenton, the majority of enlistments in Washington's army were up. When the soldiers were promised additional pay, not one stepped forward. Washington then appealed to their loyalty to a noble cause, and then, and only then, because of their trust in and respect for their general, did the men step forward).

1 Comments on Crossroads of the Revolution, last added: 2/22/2010

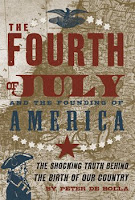

Was July 1 really America's Independence Day? Peter de Bolla, writing in The Fourth of July, offers a very different version of America's actual birthday:

Was July 1 really America's Independence Day? Peter de Bolla, writing in The Fourth of July, offers a very different version of America's actual birthday:

"Many of those present recognized that by the end of Monday, July 1, 1776, the resolution was fait accompli. This was certainly the view of of the man who is said to have cast the first vote for independence, Josiah Bartlett, a physician from New Hampshire. He had written from Philadelphia to John Langdon on 1 July: 'The affair of Independency has been the day determined in a Committe of the Whole; by next post I expect you will receive a formal declaration of the reasons . . .' So a case could be mounted for proposing 1 July as the significant punctual moment, especially given the fact that notwithstanding the secrecy which surrounded the deliberations of the Committee of the whole, it would appear that the entire city was aware what was happening."

In a new paperback edition released this month, author and historian Peter de Bolla explores the ritual and mythology of American Independence Day. The Fourth of July and the Founding of America traces the the holiday's history, from 1776 through the Civil War, the Cold War and the present.

In a new paperback edition released this month, author and historian Peter de Bolla explores the ritual and mythology of American Independence Day. The Fourth of July and the Founding of America traces the the holiday's history, from 1776 through the Civil War, the Cold War and the present.

Book Editor Colette Bancroft of the St. Petersburg Times takes note: "With July 4 coming up, a new book looks at the nation's past. The Fourth of July and the Founding of America: The Shocking Truth Behind the Birth of Our Country (Overlook) by Peter de Bolla is a historian's take on what the holiday really represents. Think it commemorates the day the Declaration of Independence was signed? Think again!"

Greetings, guys, and Happy Fourth of July.

OK, the Fourth is actually tomorrow, but we're closed then, so I'll do it today. Are any of you going to see some good fireworks? Where will you go? Where are the best fireworks in your area?

We're celebrating our independence this weekend, not only from England but from all forms of tyranny and oppression. Sure, our country's not perfect, but we have a lot of freedoms that many places in world don't. One of them is the right to read. Dictators don't like it when their people

can read and

are free to read. It undermines their ability to oppress.

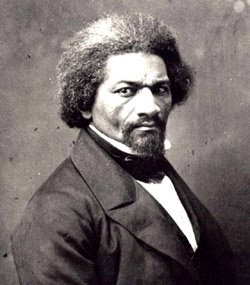

Frederick Douglas certainly knew it. He told a story about how his master's wife started teaching him to read. The master made her stop because reading would make "unfit" to be a slave. He'd learn new things and become "unsatisfied" with his life. And it was true. Frederick Douglas continued to learn anyway, eventually found his freedom, and became a nationally-famous speaker against slavery.

READING IS IMPORTANT, GUYS! Don't ever forget it.

Enough talk--let's put this into practice. Here are a couple of really good books for the Fourth or any time:

DK Eyewitness Books--American Revolution

The cover says, "Discover how a few brave patriots battled a great empire." It's true. The American Revolution was an amazing story--a nation of farmers and shopkeepers, a country that was just a strip of land between the mountains and the sea, took on and beat the greatest military power in the world. Of course, we had some help with people like

LaFayette and

countries like France, but, still, we came awfully close to losing and it's amazing that we won. This book, like all the

DK Eyewitness books, gives you lots of good pictures, interesting facts, and makes a good introduction to this fascinating story.

The Journey of the One and Only Declaration of Independence by Judith St. George

What a story!! Can you believe we still have the original Declaration? A piece of parchment over 200 years old? It's amazing to think of that--especially when I often can't find the piece of paper I printed 30 minutes ago! The original document of the Declaration of Independence is on display in Washington D. C. but it went through a lot to get there--it had to sneaked away from the British (twice!!), shrank in the hot and humid Washington summers, endured years of chimney and cigar smoke, and was both neglected and fought over many times before finding a place in its permanent display. This book told me a very exciting story that I never knew about. Judith St. George (who wrote the award-winning book

So You Want to Be President?) for making history come alive and interesting and fun to read. And Will Hillenbrand's great illustrations really add to the story.

Enjoy the weekend. Liberty forever!

Carl and Bill

Back home in Canberra the prime minister is making this historic apology on behalf of the people of Australia:

Today we honour the Indigenous peoples of this land, the oldest continuing cultures in human history.

We reflect on their past mistreatment.

We reflect in particular on the mistreatment of those who were Stolen Generations—this blemished chapter in our nation’s history.

The time has now come for the nation to turn a new page in Australia’s history by righting the wrongs of the past and so moving forward with confidence to the future.

We apologise for the laws and policies of successive Parliaments and governments that have inflicted profound grief, suffering and loss on these our fellow Australians.

We apologise especially for the removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families, their communities and their country.

For the pain, suffering and hurt of these Stolen Generations, their descendants and for their families left behind, we say sorry.

To the mothers and the fathers, the brothers and the sisters, for the breaking up of families and communities, we say sorry.

And for the indignity and degradation thus inflicted on a proud people and a proud culture, we say sorry.

We the Parliament of Australia respectfully request that this apology be received in the spirit in which it is offered as part of the healing of the nation.

For the future we take heart; resolving that this new page in the history of our great continent can now be written.

We today take this first step by acknowledging the past and laying claim to a future that embraces all Australians.

A future where this Parliament resolves that the injustices of the past must never, never happen again.

A future where we harness the determination of all Australians, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, to close the gap that lies between us in life expectancy, educational achievement and economic opportunity.

A future where we embrace the possibility of new solutions to enduring problems where old approaches have failed.

A future based on mutual respect, mutual resolve and mutual responsibility.

A future where all Australians, whatever their origins, are truly equal partners, with equal opportunities and with an equal stake in shaping the next chapter in the history of this great country, Australia.

Today I am proud to be Australian.

Sometimes it really sucks to be so far from home . . .

Elvin Lim is Associate Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and is the author of The Lovers’ Quarrel: The Two Foundings and American Political Development and The Anti-Intellectual Presidency. He blogs at www.elvinlim.com and his column on politics appears on the OUPblog regularly.

I read the Scarlett Stockings Spy when I teach the Revolutionary War. It also works wonders to help teach figurative langauge devices such as onomotapoeia, similes, and metaphors. What a good story. I'll have to check out a few of the other ones. I love teaching history!