|

-

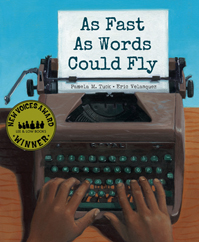

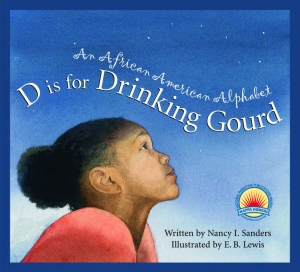

D is for Drinking Gourd: An African American Alphabet Author: Nancy I. Sanders Illustrator: E. B. Lewis Publisher: Sleeping Bear Press Book’s Website: www.DrinkingGourdAlphabet.wordpress.com

Mini Interview

Q. What is a typical writing day like for you? A. Over the years, my writing schedule has reflected the seasons in my life. When I first started writing, I had a newborn and a two-year old. When I was busy caring for the boys during the day, I was constantly brainstorming ideas. When I put them down for their naps, I’d sit down to write. Now I have the luxury of writing from the moment I get up until my husband, Jeff, comes home from teaching fourth grade in a public elementary school. Both our sons are grown and gone and live nearby. So I can be found writing some days from 6:00 a.m. until 6:00 p.m. It’s a writer’s dream come true! I keep pinching myself to make sure it’s real, but know as new phases and stages of life come by, new writing schedules will appear.

Every other week or so I have writing groups that meet in my home, so I’m usually writing four full days a week. Before breakfast, I work on little projects such as submitting my current book for state reading lists and awards. After breakfast, I work all morning on my current major project, which over the years has usually been a book deadline. After lunch, I work on short writing projects such as magazine articles, social networking, marketing, new book proposals, and writing for my church.

Q. Where do you write? A. Now that our sons are grown, I have the luxury of writing all over the house! I remember those early years of writing on a card table on our porch or on a desk squeezed in the corner of our bedroom. I guess those memories help me appreciate all the space I can write in today!

In our office, there are three desks. Two of them are my writing desks. One desk is where my desktop is. The other desk is where my laptop is. Each desk has research books, file folders, and notes on a major writing project I’m currently working on.

I split half my computer time between my desktop and my laptop. Alternating between the two helps keep my eyestrain and wrist strain to a minimum. Also, I carry my laptop out to my couch/recliner where I can type with our two writing buddies, our kittens Sandman and Pitterpat, napping next to me. A

By: Bianca Schulze,

on 2/10/2012

Blog: The Children's Book Review

( Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Ages 4-8, Ages 9-12, Picture Books, Book Lists, Black History Month, Civil Rights, African American, featured, Kadir Nelson, James E. Ransome, Ntozake Shange, Kelly Starling Lyons, Shane W. Evans, Daniel Minter, Diane Dillon, Leo Dillon, Rod Brown, Taye Diggs, Cultural Wisdom, Jessie Carney Smith, Lean’tin Bracks, Margaree King Mitchell, Patricia C. McKissack, Add a tag

By Nicki Richesin, The Children’s Book Review

Published: February 11, 2012

In celebration of African American History month, I discovered some especially moving books to share with The Children’s Book Review. Fighting for justice and equality through solidarity and courage, these books uncover the truth of the African American experience whether it’s during the time of the Civil War, Reconstruction, the Civil Rights Movement or even today.

By Kadir Nelson

In truly stunning paintings, Nelson follows the trajectory of the African-American experience in all of its harrowing and haunting glory. Beginning with slavery and ending with the civil rights movement, he gently describes the events to enlighten and as he explains in his gentle prologue, “make some things known before they’re gone for good.” You’ll find more details on Nelson’s remarkable book in these two stories from NPR and The New York Times and additional notes from the publisher. (Ages 8-11. Publisher: HarperCollins)

By Margaree King Mitchell; illustrated by James E. Ransome

It’s almost incredible to recall that Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong were not allowed as audience members in many of the theaters where they performed sold-out, standing-room-only shows. In Mitchell’s story, a small-town woman with a magnificent voice decides to bring her granddaughter along on tour. Although they are harassed, refused service and even payment from one stage manager, Grandmama keeps singing to inspire and bring people together with courage and the power of her conviction. (Ages 5-9. Publisher: HarperCollins)

By Shane W. Evans

In this eloquent book by Shane W. Evans, author of Underground, he recounts the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. His bold illustrations depict families as they make their way to the Lincoln

By: Lauren,

on 9/30/2011

Blog: OUPblog

( Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

memorial, mlk, *Featured, bunker hill, making slavery history, margot minardi, monument, monument’s—limitations, bunker, US, controversy, civil rights, Martin Luther King, Add a tag

By Margot Minardi

The new Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial in Washington, DC, attracted criticism from an unlikely corner recently when poet Maya Angelou complained that one of the inscriptions made the civil rights leader seem like an “arrogant twit.” In a sermon on “The Drum Major Instinct,” delivered two months before

If you have been under a rock the last few months, let me help you escape. The Help is an entertaining, eye-opening, jaw-dropping novel about the lives of one young woman who is white, 23 years old, and in a southern protocol prison, and how two maids, "the help," helped her escape.

The Help is about two extraordinary black maids, trying to make a living and trying to survive working for pennies for an array of fussy, social-climbing, vindictive white women. Before they know it they are authors and creating quite a stir in the town of Jackson, Mississippi. Didn't live during 1962? Not a problem. You will get this book.

ENDERS' Rating: *****

Kathryn's Website

By: Lauren,

on 5/16/2011

Blog: OUPblog

( Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

American Experience, Freedom Riders, Raymond Arsenault, bloody sunday, *Featured, freedom rides, racial justice, ray arsenault, whites only, ku klux klan, slave market, PBS, US, civil rights, oprah, birmingham, bus, violence, African American Studies, documentary, KKK, massacre, college students, scottsboro, NAACP, Add a tag

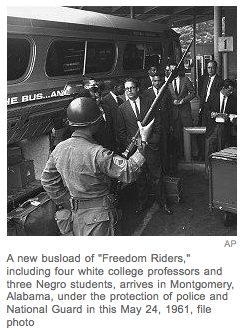

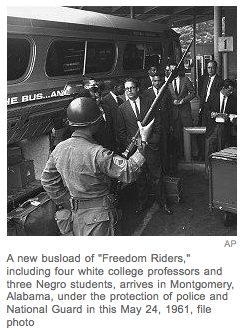

Raymond Arsenault was just 19 years old when he started researching the 1961 Freedom Rides. He became so interested in the topic, he dedicated 10 years of his life to telling the stories of the Riders—brave men and women who fought for equality. Arsenault’s book, Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, is tied to the much-anticipated PBS/American Experience documentary “Freedom Riders,” which premiers on May 16th.

In honor of the Freedom Rides 50th anniversary, American Experience has invited 40 college students to join original Freedom Riders in retracing the 1961 Rides from Washington, DC to New Orleans, LA. (Itinerary, Rider bios, videos and more are available here.) Arsenault is along for the ride, and has agreed to provide regular dispatches from the bus. You can also follow on Twitter, #PBSbus.

Day 6–May 13: Nashville, TN, to Birmingham, AL

Day 6 started with a torrential downpour–the first bad weather of the trip–that prevented us from walking around the Fisk campus and touring Jubilee Hall and the chapel. So we headed south for Birmingham, passing through Giles County, the birthplace of the Ku Klux Klan, and by Decatur, AL, the site of the 1932 Scottsboro trial. We arrived in Birmingham in time for lunch at the Alabama Power Company building, a corporate fortress symbolic of the “new” Birmingham. We spent the afternoon at the magnificent Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, where we were met by Freedom Riders Jim Zwerg and Catherine Burks Brooks, and by Odessa Woolfolk, the guiding force behind the Institute in its early years. Catherine treated the students to a rollicking memoir of her life in Birmingham, and Odessa followed with a moving account of her years as a teacher in Birmingham and a discussion of the role of women in the civil rights movement. Odessa is always wonderful, but she was particularly warm and humane today. We then went across the street for a tour of the 16th Street Baptist Church, the site of the September 1963 bombing that killed the “four little girls.”

The rest of the afternoon was dedicated to a tour of the Institute; there is never enough time to do justice to the Institute’s civil rights timeline, but this visit was much too brief, I am afraid. Seeing the Freedom Rider section with the Riders, especially Jim Zwerg and Charles Person who had searing experiences in Birmingham in 1961, was highly emotional for me, for them, and for the students. As soon as the Institute closed, we retired to the community room for a memorable barbecue feast catered by Dreamland Barbecue, the best in the business. We then went back across the street to 16th Street for a freedom song concert in the sanctuary. The voices o

By: Lauren,

on 5/13/2011

Blog: OUPblog

( Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

whites only, arsenault, riders, rides, raymond, anniston, seigenthaler, American Experience, Freedom Riders, Raymond Arsenault, *Featured, freedom rides, racial justice, ray arsenault, sweet home alabama, vanderbuilt, PBS, US, civil rights, oprah, nashville, bus, violence, African American Studies, documentary, college students, Add a tag

Raymond Arsenault was just 19 years old when he started researching the 1961 Freedom Rides. He became so interested in the topic, he dedicated 10 years of his life to telling the stories of the Riders—brave men and women who fought for equality. Arsenault’s book, Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, is tied to the much-anticipated PBS/American Experience documentary “Freedom Riders,” which premiers on May 16th.

In honor of the Freedom Rides 50th anniversary, American Experience has invited 40 college students to join original Freedom Riders in retracing the 1961 Rides from Washington, DC to New Orleans, LA. (Itinerary, Rider bios, videos and more are available here.) Arsenault is along for the ride, and has agreed to provide regular dispatches from the bus. You can also follow on Twitter, #PBSbus.

Day 5–May 12: Anniston, AL, to Nashville, TN

Our fifth day on the road started with the dedication of two murals in Anniston, at the old Greyhound and Trailways stations. I worked with the local committee on the text, and I was pleased with the results. In the past, there was nothing to signify that anything historic had happened at these sites. The turnout of both blacks and whites was gratifying and perhaps a sign that Anniston has begun the healing process of confonting its dark past. The students seemed intrigued by the whole scene, including the media blitz. We then boarded the bus and traveled six miles to the site of the bus burning; we talked with the only local resident who was there in 1961 and with the designer of a proposed Freedom Rider park that will be built on the site, which now boasts only a small historic marker. I have mixed feelings about the park, but perhaps the plan will be refined to a less Disneyesque form. It was quite a scene at the site, but we eventually pulled ourselves away for the long drive to Nashville.

Our first stop in Nashville was the civil rights room of the public library, the holder of one of the nation’s great civil rights collections. Rip Patton gave a moving account of his life as a Nashville student activist. We then traveled across town to the John Seigenthaler First Amendment Center at Vanderbilt University, where John Seigenthaler talked with the students for a spellbinding hour. He focused on his experiences with the Kennedy brothers and his sense of the evolution of their civil rights consciousness. As always, he was captivating and gracious, and full of truth-telling wit. We gave the students the night off to experience the music scene in Nashville, while I and the Freedom Riders participated in a Q and A session following a screening of the PBS film. The theater was packed, and the response was very enthusiastic. It was great to see this in Nashville, a hallowed site essential to the Freedom Rider saga and the wider freedom struggle. On to Fisk this morning before journeying south to Birmingham and “sweet home Alabama.”

Raymond Arsenault is the John Hope Franklin Professor of Southern History and and Director of Graduate Studies for the Florida Studies Program at the University of South Florida, St. Petersburg. You can watch his discussion with dire

By: Lauren,

on 5/12/2011

Blog: OUPblog

( Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

PBS, US, civil rights, oprah, Martin Luther King, bus, violence, African American Studies, documentary, KKK, college students, 1961, coretta scott, American Experience, Freedom Riders, Raymond Arsenault, *Featured, freedom rides, racial justice, ray arsenault, whites only, arsenault, riders, rides, raymond, anniston, augusta, Add a tag

Raymond Arsenault was just 19 years old when he started researching the 1961 Freedom Rides. He became so interested in the topic, he dedicated 10 years of his life to telling the stories of the Riders—brave men and women who fought for equality. Arsenault’s book, Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, is tied to the much-anticipated PBS/American Experience documentary “Freedom Riders,” which premiers on May 16th.

In honor of the Freedom Rides 50th anniversary, American Experience has invited 40 college students to join original Freedom Riders in retracing the 1961 Rides from Washington, DC to New Orleans, LA. (Itinerary, Rider bios, videos and more are available here.) Arsenault is along for the ride, and has agreed to provide regular dispatches from the bus. You can also follow on Twitter, #PBSbus.

Day 4–May 11: Augusta, GA, to Anniston, AL

As we left Augusta, I gave a brief lecture on Augusta’s cultural, political, and racial history–emphasizing several of the region’s most colorful and infamous characters, notably Tom Watson and J. B. Stoner. Then we settled in for the long bus ride from Augusta to Atlanta, a journey that the students soon turned into a musical and creative extravaganza featuring new renditions of freedom songs, original rap songs, a poetry slam–all dedicated to the original Freedom Riders. These kids are quite remarkable.

In Atlanta, our first stop was the King Center, where we were met by Freedom Riders Bernard Lafayette and Charles Person. Bernard gave a fascinating impromptu lecture on the history of the Center and his experiences working with Coretta King. We spent a few minutes at the grave sight and reflecting pool before entering the newly restored Ebenezer Baptist Church. The church was hauntingly beautiful, especially so as we listened to a tape of an MLK sermon and a following hymn. The kids were riveted.

Our next stop was Morehouse College, King’s alma mater, where we were greeted by a large crowd organized by the Georgia Humanities Council. After lunch and my brief keynote address, the gathering, which included 10 Freedom Riders, broke into small groups for hour-long discussions relating the Freedom Rides to contemporary issues. Moving testimonials and a long standing ovation for the Riders punctuated the event. Later in the afternoon, we headed for Alabama and Anniston, taking the old highway, Route 78, just as the CORE Freedom Riders had on Mother’s Day morning, May 14, in 1961. However, unlike 1961’s brutal events, our reception in Anniston, orchestrated by a downown redevelopment group known as the Spirit of Anniston, could not have been more cordial. A large interracial group that included the mayor, city council members, and a black state representative joined us for dinner before accompanying us to the Anniston Public Library for a program highlighted by the viewing of a photography exhibit, “Courage Under Fire.” The May 14, 1961 photographs of Joe Postiglione were searing, and their public display marks a new departure in Anniston, a community that until recently seemed determined to bury the uglier aspects of its past. The whole scene at the library was deeply emotional, almost surreal at times. The climax was a confessional speech b

By: Lauren,

on 5/10/2011

Blog: OUPblog

( Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

PBS, US, civil rights, oprah, bus, violence, African American Studies, documentary, greensboro, college students, 1961, American Experience, Freedom Riders, Raymond Arsenault, *Featured, freedom rides, racial justice, ray arsenault, whites only, arsenault, riders, lunch counter, lynchburg, Add a tag

Raymond Arsenault was just 19 years old when he started researching the 1961 Freedom Rides. He became so interested in the topic, he dedicated 10 years of his life to telling the stories of the Riders—brave men and women who fought for equality. Arsenault’s book, Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, is tied to the much-anticipated PBS/American Experience documentary “Freedom Riders,” which premiers on May 16th.

In honor of the Freedom Rides 50th anniversary, American Experience has invited 40 college students to join original Freedom Riders in retracing the 1961 Rides from Washington, DC to New Orleans, LA. (Itinerary, Rider bios, videos and more are available here.) Arsenault is along for the ride, and has agreed to provide regular dispatches from the bus. You can also follow on Twitter, #PBSbus.

Day 1-May 8: Washington to Lynchburg,VA

Glorious first day. Student riders are a marvel–bright and engaged. Began with group photo in front of old Greyhound station in DC, where the 1961 Freedom Ride originated. On to Fredericksburg and a warm welcome at the University of Mary Washington, where James Farmer spent his last 14 years. One of the student riders, Charles Lee is a UMW student. Second stop at Virginia Union in Richmond, where the 1961 Riders spent their first night. Greeted by VU Freedom Rider Reginald Green, charming man who as a young man sang doo-wop with his good friend Marvin Gaye. Third stop in Petersburg, where former Freedom Rider Dion Diamond and Petersburg native led a walking tour of a town suffering from urban blight; drove by Bethany Baptist, where the 1961 Riders held their first mass meeting. On to Farmville and the Robert Russa Moton Museum, formerly Moton High School, the site of the famous 1951 black student strike led by Barbara Johns; our student riders were spellbound by a panel discussion featuring 2 of the students involved in the 1951 strike and later in the struggle against Massive Resistance in Farmville and Prince Edward County, where white supremacist leaders closed the public schools from 1959 to 1964. On to Lynchburg, where the 1961 Freedom Riders spent their third night on the road and where we ended a long but fascinating first day. Heade for Danville, Greensboro, High Point, and Charlotte this morning. Buses are a rollin’!!!

Day 2-May 9: Lynchburg, VA, to Charlotte, NC

The second day of the Student Freedom Ride was full of surprises. We left Lynchburg early in the morning bound for Charlotte. We passed through Danville, once a major site of civil rights protests, where the 1961 Freedom Riders encountered their first opposition and experienced their first small victory–convincing a white station manager to relent and let three white Riders eat a “colored only” lunch counter.

Our first stop was in Greensboro, where we toured the new International Civil Rights museum, located in the famous Woolworth’s–site of the February 1, 1960 sit-in. This was my first visit to the museum, even though I was one of the historical consul

By: Lauren,

on 5/10/2011

Blog: OUPblog

( Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

PBS, US, civil rights, oprah, bus, violence, African American Studies, documentary, Freedom Riders, Raymond Arsenault, *Featured, freedom rides, Audio & Podcasts, racial justice, ray arsenault, whites only, arsenault, riders, Add a tag

This article and audio component was produced by Adam Phillips of Voice of America.

The American South was a segregated society 50 years ago. In 1960, the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed racial segregation in restaurants and bus terminals serving interstate travel, but African-Americans who tried to sit in the “whites only” section risked injury or even death at the hands of white mobs. In May of 1961, groups of black and white civil rights activists set out together to change all that.

[See post to listen to audio]

They called themselves “Freedom Riders.” An integrated group of young civil rights activists decided to confront the racist practices in the Deep South, by travelling together by bus from Washington D.C. to New Orleans, Louisiana. Raymond Arsenault documents their trip in “Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice.” He says many elder civil rights leaders denounced their strategy as a dangerous provocation that would set back the cause.

“But the members of the Congress of Racial Equality that came up with this idea, the young activists, were absolutely determined that they were going to force the issue, that they had to fight for ‘freedom now,’ not ‘freedom later,’ [and] that someone had to take the struggle out of the courtroom and into the streets, even if it meant for death for some of them. They were willing to die to make this point,” said Arsenault.

The group boarded a Greyhound bus in Washington on May 4. They planned to stop and organize others along the way until they reached their destination on May 17. Like Martin Luther King, Jr. and other prominent civil rights activists of the day, the Freedom Riders were trained in the techniques of non-violent direct action developed by the Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi. Arsenault says that for some of them, non-violence was a deeply held philosophy. For others, it was a tactic to win public support for their struggle. The group boarded a Greyhound bus in Washington on May 4. They planned to stop and organize others along the way until they reached their destination on May 17. Like Martin Luther King, Jr. and other prominent civil rights activists of the day, the Freedom Riders were trained in the techniques of non-violent direct action developed by the Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi. Arsenault says that for some of them, non-violence was a deeply held philosophy. For others, it was a tactic to win public support for their struggle.

“Part of what they did was they dressed very well, almost like they were going to church and they were absolutely committed to not striking back and being polite, and to contrast their behavior with what they saw as the white thugs who might very well attack them, and of course did,” added Arsenault.

The Freedom Riders were taunted – and attacked – throughout the South. John Lewis, now a U.S. Congressman, was badly beaten in South Carolina. Worse trouble awaited the Freedom Riders in Birmingham, Alabama, where white supremacists beat the Riders with clubs and chains while police looked on. In Anniston, Alabama, a mob surrounded the bus, slashed its tires, and firebombed it on a lone stretch of highway outside of town.

In interviews culled from “Freedom Riders“, a new PBS documentary tied to Arsenault’s book, several of the Riders recall how they narrowly escaped death.

“I can’t tell you if I walked off if I walked off the bus or crawled off, or someone pulled me off,” said one woman.

“When I got off the bus, a man came up to me, and I am coughing and strangling and he said ‘Boy, are you alright?’ And I nodded, and the next thing I knew I was on the ground. He had hit me with a baseball bat,

Carole Boston Weatherford is the vibrant author of some of the best children’s books exploring African-American history. I met Carole a year ago after she flew up from North Carolina to come visit our school library. As a snowstorm barreled in that day, we had to change our schedule at the last minute. Carole mastered the situation with grace and verve, adjusting each of her three sessions to relate perfectly to the age group. She recited poems to the youngest; she had children participating by chanting, jingling bells and tapping a triangle. They left the library joyous and inspired. Carole Boston Weatherford is the vibrant author of some of the best children’s books exploring African-American history. I met Carole a year ago after she flew up from North Carolina to come visit our school library. As a snowstorm barreled in that day, we had to change our schedule at the last minute. Carole mastered the situation with grace and verve, adjusting each of her three sessions to relate perfectly to the age group. She recited poems to the youngest; she had children participating by chanting, jingling bells and tapping a triangle. They left the library joyous and inspired.

Image via Wikipedia

With the fourth and fifth-graders, she discussed Freedom on the Menu: The Greensboro Sit-Ins and presented a sensitive and nuanced look at Jim Crow as it still existed when she was a child in Baltimore. She showed a photograph of the park where she and her family were not allowed to go. The students were solemn and spellbound. Carole Boston Weatherford knows how to make history real to children.

One of my favorite read-alouds for Black History Month, is Freedom on the Menu (Dial, 2004), which works well with ages 6-10. Told from the point of view of eight-year-old Connie, the story takes readers to the Woolsworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, NC. Connie and her mother often stop there for a soda after shopping downtown. Connie would like to sit down and have a banana split instead, but can’t; only whites may sit at the counter. “All over town signs told Mama and me where we could and couldn’t go,” Connie lamented. Lagarrigue’s somber, impressionistic paintings show the hateful Jim Crow signs that warp the community. Changes are in the air, though, as the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. comes to town. Connie sees her older siblings become politically involved and join in the lunch counter sit-ins. As the protests spread through the South, laws change. Six months later, Connie gets to savor her banana split at the counter, and it tastes like so sweet — like freedom. The author’s note about the 1960 Greensboro sit-ins provides additional information that will help young people understand the Civil Rights movement. See Weatherford’s web site for lesson plans inspired by this exemplary picture book.

And don’t miss these treasures …

For older children:

The Beatitudes: From Slavery to Civil Rights. illus. by Tim Ladwig. Eerdmans, 2009. Ages 7-12. Anyone looking for a picture book to illustrate the role of faith in helping people survive and eventually overcome tragedy should take a look at this beautiful book. While the religious tone might be too heavy for some people, there is a place for a book that fosters faith in God and respect for all.

Birmingham, 1963. Wordsong, 2007.

View Next 25 Posts

|

[…] In this series, I’ve looked at: Integrating reading, writing, speaking, and listening in grades K-1 Integrating reading, writing, speaking, and listening in grades 2-3 […]