new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Dialogue, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 50 of 123

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Dialogue in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

Today we welcome one of the founding members of #WeNeedDiverseBooks to the blog. Author Stacey Lee shares some great tips for writing delicious dialogue...though I have to disagree with her on one thing: I LOVE plotting! Thank you, Stacey, for making us all hungry for some Ben & Jerry's!

The Word on Dialogue (Read If You Like Ice Cream): A Craft of Writing Post by Stacey Lee

Of all the elements that make up a book, every writer has one that, like a favorite toy, is just more fun to play with. One of my critique partners loves writing internal monologue, while another goes bananas over world building. Everyone has her thing. (Except for plotting. No one really likes plotting.) My thing is dialogue.

Dialogue is to story what peanut butter is to Ben & Jerry’s Chubby Hubby ice cream – the magic ingredient that makes the whole tub disappear in one sitting. Those little bits of peanutty goodness keep you wanting just one more taste, one more delicious chapter. Dialogue breaks up the monotony of what would otherwise be a pint of boring vanilla.

Dialogue also helps flesh out each character’s personality. We should learn a lot about someone by what they say and how they say it. Last, dialogue moves forward plot. Consider this example from the Princess Bride:

Westley: “Hear this now, I will always come for you.”

Buttercup: “But how can you be sure?”

Westley: “This is true love. You think this happens every day?”

These simple lines tell us a lot about Westley. He’s romantic, heroic, and he has a sense of humor. The plot also progresses. We know that Westley will come for Buttercup, and anticipate that reunion.

Now that I’ve impressed you with the importance of dialogue, here are my five hot tips for working with it.

1.

Give information via dialogue. Because dialogue is such a multi-tasker, better to give information via dialogue than through narration. If you find you have paragraph upon paragraph of text, try transforming it into dialogue. You get bonus points if you break up dialogue with action or internal monologue. Back to that container of Chubby Hubby, no one wants to eat a full tub of only peanut butter. Unless of course you’re on a bad date and need an excuse not to talk. Not that this has ever happened.

Here’s an example of transforming narration to dialogue using the characters from my novel

UNDER A PAINTED SKY, which is narrated by the main character, Samantha.

Narration:

We study a handsome firearm with a sharp nose, lying on the chair. The grocer Mr. Trask kept one just like it in a cigar box by his register. I never even held one before, but maybe Annamae has. I just hope I won’t shoot myself in the foot.

Transformed to dialogue interspersed with action and internal monologue:

I point to the firearm. “That’s a Colt Dragoon.” Mr. Trask the grocer kept one just like it in a cigar box by his register.

Annamae frowns. “You know how to shoot that?”

“Only how not to shoot my foot.”

Better, right? The story becomes more active with the dialogue, we get a sense of Samantha and Annamae’s personalities, and we are more likely to remember this information than if it came in the middle of a text heavy paragraph.

2.

Cut dialogue tags where possible. Let the action and context show you who is speaking. Dialogue tags can overwhelm a scene, and disrupt the flow of the narrative. In the above example, no dialogue tags are used. The reader knows who is speaking because of where dialogue is placed, or even because of particular speech patterns. Back in the old days, the books we read used dialogue tags, and so that’s how we thought it was done. Thankfully, styles have changed for the better.

3.

Give every character his or her own unique way of speaking. This could be through dialect, word choice, speech length, slang, etc. A common beginner’s writing mistake is when everyone comes out sounding exactly alike. The pattern of speech should reflect the character’s personalities. Are they confident or shy? What is their sense of humor – dry, cheesy? Are they optimists, or pessimists? Idealists? A good writer will be able to convey who is speaking simply by how they speak.

Let’s do a mini exercise. Say a character needs to use the bathroom. How would the following characters express this need? I will do the first two, and you do the last.

Yoda: “A leak, I must take.”

Princess Leia: “I happen to like nice bathrooms.”

Han Solo:

Darth Vadar:

4.

Make every word count. It is possible to overdo dialogue. No one likes to listen to long, boring speech. Readers do not need to know every word your character says, just the important ones. SCBWI Executive Director Lin Oliver once said, “Dialogue should be the conversations you would want to eavesdrop on, not the things you tune out.”

5.

Sound natural. The goal is to approximate speech you hear in real life. You don’t have to use full and complete sentences, and sometimes your dialogue may not even be grammatically correct (e.g., see Yoda example in #3). But the more realistic your dialogue sounds, the less you risk your readers being pulled out of the story. If you struggling with dialogue, write for content first, then edit so that it sounds natural.

Stacey puts down her pen. “Now let’s all have some Chubby Hubby together!”

About the Author:

Debut author

Stacey Lee is a fourth generation Chinese-American whose people came to California during the heydays of the cowboys. She believes she still has a bit of cowboy dust in her soul. A native of southern California, she graduated from UCLA then got her law degree at UC Davis King Hall. She plays classical piano, raises children, and writes YA fiction. As a

founding member of the grassroots #WeNeedDiverseBooks movement, Stacey is a highly vocal participant in a discussion that is making waves within the publishing industry. As their legal liaison, she has participated in and/or moderated diversity panels across the country.

Website |

Twitter |

Goodreads About the Book:

Missouri, 1849: Samantha dreams of moving back to New York to be a professional musician--not an easy thing if you're a girl, and harder still if you're Chinese. But a tragic accident dashes any hopes of fulfilling her dream, and instead, leaves her fearing for her life. With the help of a runaway slave named Annamae, Samantha flees town for the unknown frontier. But life on the Oregon Trail is unsafe for two girls, so they disguise themselves as Sammy and Andy, two boys headed for the California gold rush.

Sammy and Andy forge a powerful bond as they each search for a link to their past, and struggle to avoid any unwanted attention. But when they cross paths with a band of cowboys, the light-hearted troupe turn out to be unexpected allies. With the law closing in on them and new setbacks coming each day, the girls quickly learn that there are not many places to hide on the open trail.

An unforgettable story of friendship and sacrifice--perfect for fans of Code Name Verity.Amazon |

Indiebound |

Goodreads -- posted by Susan Sipal,

@HP4Writers

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote here about dialogue tags, the little bits in a piece of writing that indicate someone has spoken. Author Martyn V. Halm discusses some additional ways to deal with said and tagging in WRITING: Dialogue and the 'Said' Rule.

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote here about dialogue tags, the little bits in a piece of writing that indicate someone has spoken. Author Martyn V. Halm discusses some additional ways to deal with said and tagging in WRITING: Dialogue and the 'Said' Rule.

Also, in The Seven Deadly Sins of Dialogue, pay particular attention to Item 2, Impossible Verbing.

I caught both these articles at a Writer Unboxed Facebook discussion, by the way.

I was working on an edit this morning and it reminded me of a small writing issue that I see way too often in manuscripts. Now, some people have called me very strict when it comes to dialogue formatting, and I’d agree. I have very low tolerance for excessive dialogue tags, too much gesture/action clogging up scene, improper formatting, and fancy “said” synonyms or adverbs. What I’m about to discuss here is another one of my pet peeves. The good news is, it has a very intuitive fix, which you can begin to implement as soon as you’re aware of the issue.

This week we’re talking about proper formatting for interruptions and trailing off in dialogue. Let’s first look at examples of this done the wrong way:

I began to say, “You just never let me finish any…” when Mom interrupted me.

“That’s because there’s nothing you can say,” she moaned. “What you’ve done is so…so…” She trailed off.

Here we find both an interruption and a trailing off description (with a bonus fancy “said” synonym). We also find, and I hope this popped out at you, a lot of excess description of pretty obvious stuff. This dialogue is currently bogged down in logistic. Instead, it should really move quickly and fly off the page.

The good news is, you can accomplish that with punctuation that exists for just this purpose.

To create an interruption that everyone will recognize as such, use an em-dash where you want to end the dialogue. You create an em-dash by typing two hyphens, and most word processing programs will tie them automatically into the longer dash.

To indicate a person trialing off from their train of thought, whether in speech or narration, use an ellipse. You create one by typing three periods in a row with no space before and sometimes a space after. If there’s a pause within a sentence…like this, you don’t need a space after. If there’s a pause between sentences, use a space… And that’s really all there is.

Now we can use both of these punctuation tools to revamp the example:

“You just never let me finish any–”

“That’s because there’s nothing to say. What you’ve done is so…so…”

You’ve cut the whole “I began to say” business, and the “Mom interrupted me” because it’s all right there in the punctuation. Wham, bam, thank you, ma’am!

By: scriberess,

on 2/22/2015

Blog:

A. PLAYWRIGHT'S RAMBLINGS

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Fish in the Water,

thoughts on playwriting,

writing,

theatre,

dialogue,

entertainment,

playwriting,

Larry David,

editing process,

play characters,

Add a tag

Sitting down in front of the computer, chin in hand and thinking about playwriting. Again. Note the word, "thinking" but not the actual act of taking fingers to keyboard and producing some worthwhile dialogue. Still further delayed the process by going over finished plays and assessing whether they need fixing or editing, something I'm prone to do in both my writing and painting. Frequently, the end result is ruining any progress on whatever project I'm "fixing."

I'm an inordinate "fixer" of all my artistic undertakings, which really don't require further adjusting. Recently, I applied what I swore were the absolute final strokes to a black and white painting first started three years ago, which has been "fixed" over the years. Perhaps this will be the reality and then again, who knows.

In as far as my plays are concerned, some have been altered to the point where all objectivity has been lost as to the strongest version. Most often, the changes are relegated to small dialogue adjustments or altering what appears to me to be a weak a scene. In the end, a decision has to be made which version is the best version to submit, followed by a period of self-doubt and whether my plays are actually produce-able. Perhaps this is a common pattern with writers in general in that the selection of the right words is paramount to the whole story line. In as far as dialogue is concerned, the character has to utter words and phrases that suit her/his mannerisms, personality and mien and therein lies the challenge.

Although the actual act of submitting plays is a positive move, there is also the self-doubt that creeps in waiting for updates on their fate. Negative thoughts like:

- perhaps the wrong version was sent - whatever that is

- maybe I don't have what it takes to be a "real" playwright

- given the volume of experienced and produced playwrights, many of whom are familiar names to

the public and within the theatre community, do my literary gems stand a chance?

And so the uncertainty continues but something drives me to persevere. The possibility, whatever the odds that there is a theatre "out there" somewhere that will see something special in my plays is enough to keep me going and press on. Meanwhile, some fine tuning of the dialogue and changes to the story arc is required to Dead Writes. Really.

P.S.: just read that Larry David's new play, "Fish In the Dark" is a big hit on Broadway. It should only happen to me! Mazel-tov, Larry...or Mr. David. Good to note that good comedy will always draw a crowd.

Guest post

by author Rayne Hall

Here thirteen techniques professional writers use to make their dialogue sharp, realistic and entertaining.

1. To make fiction dialogue exciting, use questions. Questions hook the reader's interest more than statements. Let the characters talk in questions as much as possible.

Examples

“What do you want?”

“Why are you doing this?”

“Where are we going?”

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

2. To make dialogue sizzling, let characters answer questions with questions. This hints at evasion, power struggles or secrets. Each time a question is answered with another question, the tension rises.

Example 1 – Wife and Husband

“Do you still love me?”

“Why are you asking?”

“Do you still truly love me?”

“Are you suddenly doubting my love?”

“Why don’t you tell me that you still love me?”

“Do we have to talk about this now?”

“Why aren’t you answering my question?”

“What do you want me to say?”

Example 2: Police Officer and Suspect

“Where were you between ten and eleven last night?”

“Why do you want to know?”

“Where were you between ten and eleven last night?”

“Where should I have been?”

“Why don’t you tell me where you were?”

“Are you accusing me of something?”

“Do you have something to hide?”

“What makes you think I have something to hide?”

3. Let the characters do something while they talk. Give them a job, a task, an assignment, whether it's washing the dishes, mending the garden shed or cracking a safe.

4. To make fiction dialogue vivid, write it as tightly as possible, cutting superfluous words. Great fiction dialogue is less wordy than real-life conversations. One-liners have great impact.

5. To make fiction dialogue sound real, use short sentences. Real life dialogue often rambles on in long sentences, but fictional dialogue comes across as more real if the sentences are short.

6. Use tags (he said, she asked, he replied) only when they're needed for clarity of who's talking. If the characters are busy doing things, then you can simply write their spoken sentences before or after the action, and it’s clear who’s talking.

Examples:

Elsa turned the tap off. “What now?”

Ben tightened his grip on the gun. “Give me the money.”

7. Use short words for tags: he said, she asked, he yelled, she screamed. Avoid long words that draw attention to themselves: he expostulated, she interrogated.

8. Avoid adding adverbs to the tags. Instead of ‘he said loudly’ write ‘he shouted’, instead of ‘she said irritably’ write ‘she snapped’, instead of ‘he said furiously’ write ‘he yelled’, instead of ‘she said quietly’ write ‘she muttered’. Better still, let the dialogue it self imply how something is said: “I’ve had enough, you bastard!” is clear; you don’t need to add ‘he said angrily’.

9. Add body language – posture, facial expression, movements -, especially for the non-PoV character. This contributes clarity and meaning without the need for tags.

Examples:

“I don’t like this.” John scratched his ear. “Do we have to go through with it?”

Bill leant forward. “Tell me more.”

Jane twisted her necklace in her fingers. “What if someone sees us?”

Fred glanced at his watch. “Time to go.”

10. Hint at dishonesty or secrets by showing body language that contradicts what the character says. Use this technique sparingly.

Examples:

“No need to hurry.” Mary drummed her fingers on the table.

Mary glanced at her watch. “Take all the time you need.”

“I can wait,” Mary assured him. Her feet jiggled and bounced.

11. Frequent cusswords can make a character appear unintelligent, so use them sparingly, if at all. You may want to reserve them for a minor character who is not overly bright, or for a character who has the weaker arguments in a confrontation and is losing his cool.

12. Consider the person's level of education. A high-school dropout uses a different vocabulary than a PhD graduate. How ‘educated’ is this character’s speech?

13. Characters don't talk the way their authors do. Think of each character’s key personality traits.

How would a person with these characteristics talk? What kind of speech patterns reflect this personality?

Examples:

A self-centred person probably uses the words ‘I’, ‘my’ and ‘me’ a lot.

A timid person may preface requests and statements with an apology: “I'm sorry to bother you. I wonder if it's possible to...” “I'm probably wrong, but...”

An insecure person may use ‘maybe’, ‘perhaps’.

A bossy person may phrase many sentences as a command. “Take a taxi.” “Call me tomorrow.”

A status-seeking person may name-drop and mention status symbols at every opportunity “Last week, the duchess told me...” “When I parked my Porsche...”

A pompous person may speak in multi-syllabic words.

Which of these techniques are you already using in your fiction? Which are new?

I look forward to your comments. If you have questions, ask and I will reply.

Rayne Hall has published more than fifty books in several languages under several pen names with several publishers in several genres, mostly fantasy, horror, and non-fiction. She is the author of the bestselling Writer's Craft series and editor of the Ten Tales short story anthologies.

Having lived in Germany, China, Mongolia and Nepal, she has now settled in a small dilapidated town of former Victorian grandeur on the south coast of England where she enjoys reading, gardening and long walks along the seashore. She shares her home with a black cat adopted from the cat shelter. Sulu likes to lie on the desk and snuggle into Rayne's arms when she's writing.

By:

Carmela Martino and 5 other authors,

on 1/28/2015

Blog:

Teaching Authors

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Carmela Martino,

Writing Workout,

Sherry Shahan,

Wednesday Writing Workout,

humor,

Characterization,

exercise,

dialogue,

writing exercise,

Add a tag

As a follow-up to last Friday's

Guest TeachingAuthor Interview with Sherry Shahan, I'm repeating the

Wednesday Writing Workout she shared with us in

July 2014. After reading this post, I'm sure you'll want to enter for a chance to win a copy of Sherry's

Skin and Bones (A. Whitman), if you haven't already entered the contest.

Sherry's young adult novel is a quirky story set in an eating disorder unit of a metropolitan hospital. The main character “Bones” is a male teen with anorexia. He falls desperately in love with an aspiring ballerina who becomes his next deadly addiction.

The novel was inspired by a short story Sherry wrote years ago, “Iris and Jim.” It appeared in print eight times worldwide. Her agent kept encouraging her to expand “Iris and Jim” into a novel. Easy for her to say!

* * *

Wednesday Writing Workout

Tell It Sideways

by Sherry Shahan

During the first draft of

Skin and Bones I stumbled over a number of unexpected obstacles. How could I give a character an idiosyncratic tone without sounding flippant?

Eating disorders are serious, and in too many instances, life-threatening.

Sometimes I sprinkled facts into farcical narration. Other times statistics emerged through dialogue between prominent characters—either in an argument or by using humor. Either way, creating quirky characters felt more organic when their traits were slipped in sideways instead of straight on.

There are endless ways to introduce a character, such as telling the reader about personality:

"Mrs. Freeman could never be brought to admit herself wrong on any point." — Flannery O'Connor, "Good Country People."

Or by detailing a character’s appearance:

"The baker wore a white apron that looked like a smock. Straps cut under his arms, went around in back and then to the front again, where they were secured under his heavy waist ." —Raymond Carver "A Small, Good Thing"

The art of creating fully realized characters is often a challenge to new writers of fiction. As a longtime teacher I’ve noticed:

1.) Writers who use short cuts, such a clichés, which produce cardboard or stereotypical characters.

2.) Writers who stubbornly pattern the main character after themselves in a way that’s unrealistic.

3.) Writers who are so involved in working out a complicated plot that their characters don’t receive enough attention.

In Skin and Bones I let readers get to know my characters though humorous dialogue. This technique works best when characters have opposing viewpoints.

Consider the following scene. (Note: Lard is a compulsive over-eater; Bones is anorexic.)

“I’ll never buy food shot up with hormones when I own a restaurant,” Lard said. “Chicken nuggets sound healthy enough, but they have more than three dozen ingredients—not a lot of chicken in a nugget.”

Bones put on rubber gloves in case he’d have to touch something with calories. “Can’t we talk about something else?”

“That’s the wrong attitude, man. Don’t you want to get over this shit?”

“Not at this particular moment, since it’s almost lunch and my jaw still hurts from breakfast.”

Lard shook his head. “I’m glad I don’t live inside your skin.”

“It’d be a little crowded.”

Exercise #1: Choose a scene from a work-in-progress where a new character is introduced. (Or choose one from an existing novel.) Write a paragraph about the character without using physical descriptions. Repeat for a secondary character.

Exercise #2: Give each character a strong opinion about a subject. Do Nice Girls Really Finish Last? Should Fried Food Come With a Warning? Make sure your characters have opposing positions. Next, write a paragraph from each person’s viewpoint.

Exercise #3: Using the differing viewpoints, compose a scene with humorous dialogue. Try not to be funny just for humor’s sake. See if you can weave in a piece

of factual information (Lard’s stats. about Chicken Nuggets), along with a unique character trait (Bones wearing gloves to keep from absorbing calories through his skin.)

Creating realistic, natural-sounding dialogue in writing can be a difficult task for writers. Dialogue may come off as rigid and artificial. The most useful tool for creating an air of humanism in a character’s dialogue is the interjection.

An interjection is a noun (more of a sound) that stands alone in a sentence and is designed to convey the emotion of the speaker or narrator. By “stands alone,” we mean to say that an interjection is not grammatically connected to the sentence in which it is used.

Interjections are used by authors to add an element of realism to their prose, as humans often use interjections heavily within their everyday speech. Interjections are often followed by an exclamation mark, leading people to refer to them as “exclamations.”

Examples of interjections are:

“Ouch!” and “Wow!” or even “Cheers!” or "Huh?" or "Uh..."

“Wow! Your new car rocks!”

This sentence illustrates the function of an interjection. “Wow,” being the interjection, stands completely on its own, not connected to the subsequent sentence by anything other than context. As you can see, it is followed by an exclamation mark, adding excitement to the quote. You can imagine the character saying this with widened eyes and an excited tone while commenting on the massive spoon at which he is looking.

Compare this to saying, “That car rocks.”

The latter sentence is lifeless and conveys no emotion to the reader whatsoever. Interjections have the unique ability of being able to stand as sentences all on their own.

The exclamation “Whatever!” and "Shut up!"—often heard as a teenager storms out of a room—is an example of an interjection functioning as a one-word sentence.

Uh, so yeah, this section is about,um, filled pauses.

Another form of interjection that is useful for adding a humanistic element to dialogue is called the filled pause. These are used by people in, uh, well, a lot of spoken sentences. They are not necessarily “words” per se, but rather sounds that people make during pauses in speech.

The filled pause can be used to convey such character traits and emotions as nervousness, stupidity, indifference, or impatience. All an author must do is think about the sounds they themselves or others would make while in those situations. Imagine a nervous teenager asking out the prettiest girl in his high school, if you will.

“Hey, uh, Sylvia? I, um, was wondering if, uh, you would go to, like, a movie with me, or like whatever.”

Poor Patrick here has unwittingly used seven filled pauses in his attempt to ask Sylvia on a date. The filled pauses serve to efficiently convey his gut-wrenching nervousness.

Sylvia’s response? “Wow! Patrick! Of course!”

“Ha! Johnson, come over here and check out this photo!”

Using interjections and filled pauses may be effectively inserted within dialogue.

“I, uh, wouldn’t mind a job, but um, I can only work on weekends?”

Interjections are an excellent way of expressing emotion within the dialogue of your prose, but you must be careful not to overuse them. Used sparingly and appropriately, interjections can breathe a true sense of humanity into your character, giving them the sort of personality that readers can connect with on a deeper level. Take poor Patrick, for example; by the end of his painful plea, didn’t you feel at least a bit sorry for him? If you did, it’s thanks to the interjections.

Short List of Interjections

- Aha

- Boo

- Crud

- Dang

- Eew

- Gosh

- Goodness

- Ha

- Oh

- Oops

- Oh no

- Ouch

- Rats

- Shoot

- Uh-oh

- Uh-huh

- Ugh

- Yikes

- Yuck

Seven tools to help your dialogue be realistic, but still interesting.

http://www.writersdigest.com/online-editor/the-7-tools-of-dialogue

Don't believe everything you're told about writing dialogue.

http://www.jeshays.com/?p=662

By:

Carmela Martino and 5 other authors,

on 7/30/2014

Blog:

Teaching Authors

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

humor,

Characterization,

dialogue,

Vermont College of Fine Arts,

Carmela Martino,

Writing Workout,

Sherry Shahan,

Wednesday Writing Workout,

UCLA Extension Writers Program,

Add a tag

Today's

Wednesday Writing Workout comes to us courtesy of the talented

Sherry Shahan. Sherry and I first met virtually, when she joined the

New Year/New Novel (NYNN) Yahoo group I started back in 2009. I love the photo she sent for today's post--it personifies her willingness to do the tough research sometimes required for the stories she writes. As she says

on her website, she has:

"ridden on horseback into Africa’s Maasailand, hiked through a leech-infested rain forest in Australia, shivered inside a dogsled for the first part of the famed 1,049 mile Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race in Alaska, rode-the-foam on a long-board in Hawaii, and spun around dance floors in Havana, Cuba."

Her new young adult novel

Skin and Bones (A. Whitman) is a quirky story set in an eating disorder unit of a metropolitan hospital. The main character “Bones” is a male teen with anorexia. He falls desperately in love with an aspiring ballerina who becomes his next deadly addiction.

The novel was inspired by a short story Sherry wrote years ago, “Iris and Jim.” It appeared in print eight times worldwide. Her agent kept encouraging her to expand “Iris and Jim” into a novel. Easy for her to say!

* * *

Wednesday Writing Workout

Tell It Sideways

by Sherry Shahan

During the first draft of

Skin and Bones I stumbled over a number of unexpected obstacles. How could I give a character an idiosyncratic tone without sounding flippant?

Eating disorders are serious, and in too many instances, life-threatening.

Sometimes I sprinkled facts into farcical narration. Other times statistics emerged through dialogue between prominent characters—either in an argument or by using humor. Either way, creating quirky characters felt more organic when their traits were slipped in sideways instead of straight on.

There are endless ways to introduce a character, such as telling the reader about personality:

"Mrs. Freeman could never be brought to admit herself wrong on any point." — Flannery O'Connor, "Good Country People."

Or by detailing a character’s appearance:

"The baker wore a white apron that looked like a smock. Straps cut under his arms, went around in back and then to the front again, where they were secured under his heavy waist ." —Raymond Carver "A Small, Good Thing"

The art of creating fully realized characters is often a challenge to new writers of fiction. As a longtime teacher I’ve noticed:

1.) Writers who use short cuts, such a clichés, which produce cardboard or stereotypical characters.

2.) Writers who stubbornly pattern the main character after themselves in a way that’s unrealistic.

3.) Writers who are so involved in working out a complicated plot that their characters don’t receive enough attention.

In Skin and Bones I let readers get to know my characters though humorous dialogue. This technique works best when characters have opposing viewpoints.

Consider the following scene. (Note: Lard is a compulsive over-eater; Bones is anorexic.)

“I’ll never buy food shot up with hormones when I own a restaurant,” Lard said. “Chicken nuggets sound healthy enough, but they have more than three dozen ingredients—not a lot of chicken in a nugget.”

Bones put on rubber gloves in case he’d have to touch something with calories. “Can’t we talk about something else?”

“That’s the wrong attitude, man. Don’t you want to get over this shit?”

“Not at this particular moment, since it’s almost lunch and my jaw still hurts from breakfast.”

Lard shook his head. “I’m glad I don’t live inside your skin.”

“It’d be a little crowded.”

Exercise #1: Choose a scene from a work-in-progress where a new character is introduced. (Or choose one from an existing novel.) Write a paragraph about the character without using physical descriptions. Repeat for a secondary character.

Exercise #2: Give each character a strong opinion about a subject. Do Nice Girls Really Finish Last? Should Fried Food Come With a Warning? Make sure your characters have opposing positions. Next, write a paragraph from each person’s viewpoint.

Exercise #3: Using the differing viewpoints, compose a scene with humorous dialogue. Try not to be funny just for humor’s sake. See if you can weave in a piece

of factual information (Lard’s stats. about Chicken Nuggets), along with a unique character trait (Bones wearing gloves to keep from absorbing calories through his skin.)

I hope these exercises help you think about characterization in a less conventional way. Thanks for letting me stop by!

Sherry

www.SherryShahan.comThank you, Sherry, for this terrific Wednesday Writing Workout! Readers, if you give these exercises a try, do let us know how they work for you.

Happy writing!

Carmela

Today I'm happy to share a guest Wednesday Writing Workout from the amazing Kym Brunner, who is celebrating the release of not one, but TWO, novels this summer.

When I met Kym at an SCBWI-IL conference a few years back, I couldn't get over her enthusiasm and energy. I had no idea how she found time to write, given that she was a busy mom with a full-time teaching job (teaching middle-schoolers, no less!).

According to her bio, Kym's method of creating a manuscript is a four-step process: write, procrastinate, sleep, repeat. She's addicted to Tazo chai tea, going to the movies, and reality TV. When she's not reading or writing, Kym teaches seventh grade full time. She lives in Arlington Heights, Illinois with her family and two trusty writing companions, a pair of Shih Tzus named Sophie and Kahlua.

Kym's debut novel,

Wanted: Dead or In Love (Merit Press), was released last month. Here's the intriguing synopsis:Impulsive high school senior Monroe Baker is on probation for a recent crime, but strives to stay out of trouble by working as a flapper at her father's Roaring 20's dinner show theater. When she cuts herself on one of the spent bullets from her father's gangster memorabilia collection, she unwittingly awakens Bonnie Parker's spirit, who begins speaking to Monroe from inside her head.

Later that evening, Monroe shows the slugs to Jack, a boy she meets at a party. He unknowingly becomes infected by Clyde, who soon commits a crime using Jack's body. The teens learn that they have less than twenty-four hours to ditch the criminals or they'll share their bodies with the deadly outlaws indefinitely.

And here's the blurb for her second novel,

One Smart Cookie (Omnific Publishing), which came out July 15:

Sixteen year old Sophie Dumbrowski, is an adorably inept teen living above her family-owned Polish bakery with her man-hungry mother and her spirit-conjuring grandmother, who together, are determined to find Sophie the perfect boyfriend.

Sixteen year old Sophie Dumbrowski, is an adorably inept teen living above her family-owned Polish bakery with her man-hungry mother and her spirit-conjuring grandmother, who together, are determined to find Sophie the perfect boyfriend.

But when Sophie meets two hot guys on the same day, she wonders if this a blessing or a curse. And is Sophie's inability to choose part of the reason the bakery business is failing miserably? The three generations of women need to use their heads, along with their hearts, to figure things out...before it's too late.

Today Kym shares a terrific

Wednesday Writing Workout on dialogue.

Wednesday Writing Workout:

SHH! DIALOGUE SECRETS YOU DON’T WANT TO MISS!

by Kym Brunner

Quick! After a person’s appearance, what’s the first thing you notice when you meet someone? If you’re like most of us, it’s what comes out of their mouths. First impressions and all that. But when you read, you can’t see the characters, so your first impressions are made based on what the characters say, not how they look.

Simple concept, right? Not so simple to deliver.

SO…HOW DO YOU MAKE YOUR CHARACTER MAKE A GOOD FIRST IMPRESSION?

Give them something to say that’s:

- Believable

- Fits their personality

- Consistent, yet unexpected

- Short and natural

1) Believable DialogueHow do you know if it’s believable or not? Put on your walking shoes and get out your notebook! Head to the spot where the prototype of your character would go. Need to write teens talking together at lunch? Go to a fast-food restaurant near a high school. Want to know what couples say when they’re on a date? Head to a movie theater early and go see the latest romantic comedy. You get the idea.

***HINT: LISTEN AND TAKE GOOD NOTES. I promise you’ll forget the words and how they said them if you don’t.

2

2) Dialogue that fits the character’s personality

There’s a famous writing cliché that says a reader should be able to read a line of dialogue and know who the character is without the identifying dialogue tag.

The key is being the character when you write his or her lines. Imagine YOU are the sensitive butcher who is very observant (seriously, picture yourself looking out of the eyes of the butcher with your hands on a raw steak) and then write his or her lines. Better yet, listen to a butcher talk to customers and/or interview one to ask his top three concerns about his job. You might be surprised to learn what those things are…and so might your reader.

***HINT: SWITCH INTO THE MINDS of all of your characters (even the minor ones) as you write to create words that only THEY would say.

3) Consistent, yet unexpected? Huh?Your job is to make sure your characters are real, that they speak the truth (or not, depending on who they are). In real life, characters might keep their thoughts to themselves. Not so in fiction. Characters that are pushed to the brink must speak out––to a best friend, to the cabbie, to the offending party, to the police.

Yes, we want dialogue to be authentic, but it IS a story and it does need to intrigue your readers. So let them speak their mind and propel the story ahead by providing interesting thoughts for your readers to mull over.

***HINT: TO KEEP PACING ON TRACK, use frequent dialogue to break up paragraphs of exposition.

4) Short and NaturalCut to the chase. No one likes listening to boring blowhards, so don’t let your characters be “one of those people.” Remember tuning out a boring teacher? That’s what didactic dialogue and info dumps feels like to your readers. Only include information that’s absolutely necessary for the story’s sake and skip the rest. You might need to know the backstory, but keep it to yourself.

***HINT: READ ALL DIALOGUE OUT LOUD. Change voices to the way you imagine the characters interacting and it’ll feel more “real.” If you’re bored with the conversation, so is your reader. If it doesn't sound the way a person really talks, cut it or revise it. Listen to real people and you’ll notice most of us talk in short sentences with breaks for others to add commentary.

So there you have it. Write dialogue that’s believable, fits the characters, necessary, and natural and your readers will come back for more!

*****

Hopefully you’ll find authentic dialogue galore in

Wanted: Dead or In Love, which features two alternating POVs––one from Monroe (a modern-day teen who becomes possessed internally by the infamous Bonnie Parker), and the other from Clyde Barrow himself (who works hard to take over the body of Jack Hale, a teen male).

And if cultural humor is more your style, you’ll get a helping of Polish spirits along with a bounty of teen angst in

One Smart Cookie.

Kym BrunnerThanks so much, Kym! Readers, let us know if you try any of these techniques. Meanwhile, if you'd like to connect with Kym, you can do so via her

website,

Facebook, Twitter, and

Goodreads. And if you'd like a taste of

Wanted: Dead or In Love, here's the book trailer:

Happy writing (and reading!)

Carmela

By:

Angela Ackerman,

on 7/7/2014

Blog:

The Bookshelf Muse

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Uncategorized,

lessons,

Characters,

Dialogue,

Description,

fear,

Character Traits,

Emotion,

Flaws,

Add a tag

One of the struggles that comes with writing is when a character feels vulnerable and so tries to hide their emotions as a result. Fear of emotional pain, a lack of trust in others, instinct, or protecting one’s reputation are all reasons he or she might repress what’s going on inside them. After all, people do this in real life, and so it makes sense that our characters will too. Protecting oneself from feeling exposed is as normal as it gets.

One of the struggles that comes with writing is when a character feels vulnerable and so tries to hide their emotions as a result. Fear of emotional pain, a lack of trust in others, instinct, or protecting one’s reputation are all reasons he or she might repress what’s going on inside them. After all, people do this in real life, and so it makes sense that our characters will too. Protecting oneself from feeling exposed is as normal as it gets.

But where does that leave writers who STILL have to show these hidden emotions to the reader (and possibly other characters in the scene)?

The answer is a “TELL”– a subtle, bodily response or micro gesture that a character has little or no control over.

No matter how hard we try, our bodies are emotional mirrors, and can give our true feelings away. We can force hands to unknot, fake nonchalance, smile when we don’t mean it and lie as needed. However, to the trained eye, TELLS will leak through: a rushed voice. An off-pitch laugh. Hands that fiddle and smooth. Self-soothing touches to comfort. Sweating.

For a story to have emotional range, our characters will naturally hide what they feel at some point, and when they do, the writer must be ready. Readers will be primed for an emotional response by the scene’s build up, and will be on the lookout for a character’s body language cues and tells.

Here is a list of possible TELLS that will convey to readers that more is going on with your Protagonist than it seems:

- A voice that breaks, drops or raises in pitch; a change in speech patterns

- Micro hesitations (delayed speech, throat clearing, slow reaction time) showing a lack of commitment

- A forced smile, laugh or verbally agreeing/disagreeing in a way that does not seem genuine

- Cancelling gestures (smiling but stepping back; saying No but reaching out, etc.)

- Hands that fiddle with items, clothing and jewellery

- Stiff posture and movements; remaining TOO still and composed

- Rushing (the flight instinct kicking in) or making excuses to leave or avoid a situation

- A lack of eye contact; purposefully ignoring someone or something

- Closed body posture (body shielding, arms crossing chest, using the hair to hide the face, etc.)

- Sweating or trembling, a tautness in the muscles or jaw line

- Smaller gestures of the emotion ‘leaking out’ (see The Emotion Thesaurus for ideas that match each emotion)

- Growing inanimate and contributing less to conversation

- Verbal responses that seem to have double meanings; sarcasm

- Attempting to intimidate others into dropping a subject

Overreacting to something said or done in jest

- Increasing one’s personal space ( withdrawing from a group, sitting alone, etc.)

- Tightness around the eyes or mouth (belying the strain of keeping emotion under wraps)

- Hiding one’s hands in some way

Sometimes a writer can let the character’s true thoughts leak out and this can help show the reader what’s really being felt. But this only works if the character happens to be the Point Of View Character. The rest of the time, it comes down to micro body language and body tells that are hard, if not impossible, to control.

Have you used any of these tells to show the reader or other characters in the scene that something is wrong? What tells do you notice most in real life as you read the body language of those around you? (These real life interactions can be gold mines for fresh body language cues to apply to your characters!)

TIP: For more inspiration on body language that will convey specific emotions, flip through The Emotion Thesaurus.

TIP 2.0: Becca has a great post on Hidden Emotions as well, and how “Acting Normal” might be the go-to expressive that gets hidden emotions across to the reader, while potentially leaving other characters in the dark.

The post Hidden Emotions: How To Tell Readers What Characters Don’t Want To Show appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS.

The following is the second in a two part, guest blog post from Eleanore D. Trupkiewicz, whose short story, “Poetry by Keats,” took home the grand prize in WD’s 14th Annual Short Short Story Competition. You can read more about Trupkiewicz in the July/August 2014 issue of Writer’s Digest and in an exclusive extended interview with her online. In this post, Trupkiewicz follows up on her discussion of dialogue with an impassioned plea: stick to said.

* * * * *

Welcome back! Part I of this two-part post talked about two key aspects of writing dialogue. First, dialogue isn’t usually the place to use complete sentences because most people in everyday conversations speak in phrases and single words. Second, effective dialogue takes correct punctuation so the reader doesn’t get yanked out of the story by a poorly punctuated exchange.

Remember, the goal in writing fiction is to keep the reader engaged in the story. But don’t give up on writing to spend the rest of your life doing something easier, like finding the Holy Grail, just yet. There’s one more key aspect that makes dialogue effective for fiction writers.

Problem: The Great He Said/She Opined Debate

In Part I, I mentioned learning from my grade school English teacher about complete sentences. Another subject she covered in that class was the importance of using synonyms and avoiding repetition.

To this day, that discussion drives me absolutely crazy.

Thousands of budding writers all over the world heard those words and deduced that they would be penalized if they repeated the word said in any work of fiction they ever wrote. So they dutifully found thesauruses and started looking up other words to use.

I’d like to submit that thousands of budding writers have been misled. Here’s my take:

Stop!

Do not touch your thesaurus to find another word that means said.

The attribution said is fine. In fact, when readers are skimming along through a novel at warp speed, the word said is just like a punctuation mark—it doesn’t even register in readers’ minds (unless used incorrectly, and it would be hard to do that).

But if you draw attention to the mechanics of your story with dialogue like this, you’re guaranteed to lose your reader in total frustration:

“Luke,” she opined, “I need you.”

“Raina,” he implored, “I know you think you do, but—”

“No!” she wailed. “Please!”

Luke shouted, “You don’t know what you’re talking about!”

“You’re being so mean to me,” Raina wept.

With an exchange like that one, you might as well run screaming out of the book straight at the reader, waving a neon sign that says: HEY, DON’T FORGET THAT THIS IS ONLY A WORK OF FICTION AND THESE CHARACTERS AREN’T REAL!!!

Why would you nail yourself into your own proverbial coffin like that?

Here’s my advice. Don’t reach for the thesaurus this time. Leave it right where it is on your shelf. You might never need it again.

Instead, if you need an attribution, use said. If you must use something different for the occasional question, you could throw in “asked” for variety, but not too often.

An even better way to use attributions in dialogue is to use a beat of action instead, like this:

“I just don’t know anymore.” Mary folded her arms. “I think I’m afraid of you.”

Harry sighed. “I’m sorry.” He shook his head. “I’m not very good at this.”

That way, you know who’s talking, and you’ve even worked action and character traits into the conversation. It makes for a seamless read.

Two final thoughts:

First, dialogue cannot be smiled, laughed, giggled, or sighed. Therefore, this example is incorrect:

“Don’t tickle me!” she giggled.

You can’t giggle spoken words. You can’t laugh them or sigh them or smile them, either. (I dare you to try it. If it works for you, write me and let me know. We could be on to something.)

Of course, if you’re using said exclusively, then that won’t be a problem.

Second, let’s talk adverbs. If a writer can be convinced to use said instead of other synonyms, then he or she becomes really tempted to reach for an adverb to tell how the character said something, like this:

“I don’t want to see you again,” Lily said tonelessly.

“You don’t mean that,” Jack said desperately.

“You’re an idiot,” Lily said angrily.

The problem with using adverbs is that they’re always telling to your reader. (Remember that old maxim, “Show, don’t tell”?)

An occasional adverb won’t kill your work, but adverbs all over the place mean weak writing, or that you don’t trust your dialogue to stand without a qualifier. It’s like you’re stopping the movie (the story playing through the reader’s mind) for a second to say, “Oh, but wait, you need to know that Lily said that last phrase angrily. That’s important. Okay, roll tape.”

Why rely on a telling adverb when you could find a better way to show the reader what’s going on in the scene or inside the characters? Try something like this:

Lily turned away and crossed her arms. “I don’t want to see you again.”

“You don’t mean that.” Jack pushed to his feet in a rush.

She glared at him. “You’re an idiot.”

Beats of action reveal character emotions and set the stage far more effectively than an overdose of adverbs ever will.

Conclusion

While a challenge to write, dialogue doesn’t have to be something you dread every time you sit down to your work-in-progress (or WIP). The most effective dialogue is the conversations that readers can imagine your characters speaking, without all the clutter and distractions of synonymous attributions, overused adverbs, and incorrect punctuation.

When in doubt, cut and paste only the dialogue out of your WIP and create one script for each character. Then invite some friends (ones who don’t already think you’re crazy because you walk around mumbling to yourself about your WIP, if you still have any of those) over for dessert or appetizers sometime. Hand out the scripts, assign each person a part, and then sit back and listen. Was a line of dialogue so complicated it made the reader stumble? Do you hear places where the conversation sounds stilted and too formal, or where it sounds too informal for the scene? Does an exchange sound sappy when spoken aloud? Are there words you can cut out to tighten the flow?

And don’t give up your writing to search for the Holy Grail. While the search would be less frustrating sometimes, writing dialogue no longer has to look demonic to you. You know what to do!

Questions

In your current WIP, what sticking points and challenges do you find about writing dialogue? Is a character’s voice giving you trouble? Do you worry you’re overusing an attribution? Do you have a totally opposite opinion about adverbs? The rule about writing fiction is that there really aren’t many hard-and-fast rules, so don’t hesitate to share!

* * * * *

Eleanore D. Trupkiewicz is an author, poet, blogger, book reviewer, and freelance editor and proofreader. She writes full-length thrillers as well as short stories, flash fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction. Her blogs are Engraved: All About Writing (http://eleanoretrupkiewicz.blogspot.com) and Daily Poetry Prompts (http://dailypoetryprompts.blogspot.com) and you can find her on one of her websites at www.eleanoretrupkiewicz.com or Refiner’s Fire Editing (www.refinersfireediting.com). Follow her on Twitter: @ETrupkiewicz. She lives and writes in Colorado with cats, chocolate, and assorted houseplants in various stages of demise.

The following is a guest blog post from Eleanore D. Trupkiewicz, whose short story, “Poetry by Keats,” took home the grand prize in WD’s 14th Annual Short Short Story Competition. You can read more about Trupkiewicz in the July/August 2014 issue of Writer’s Digest and in an exclusive extended interview with her online. In this post, Trupkiewicz details the importance of creating realistic dialogue and punctuating dialogue properly in order to keep the reader invested. Even the slightest of errors can draw the reader out of the story.

To read the second part of this post, check back at the beginning of next week, where she’ll tackle “said” and other attributions.

* * * * *

If the devil’s in the details, that makes dialogue for fiction writers one of the most demonic elements of a story or novel. Just thinking about it makes me want to shut down my laptop and take up another career. Something less taxing, like dedicating the rest of my life to finding the Holy Grail.

Think about it. It couldn’t possibly be any more frustrating a career choice.

On the other hand, without dialogue to break up the monotony, stories get wordy and dull. Paragraph after paragraph of description or action eventually bores a reader into throwing the book against the wall and declaring a moratorium on any future reading.

Which is a death sentence for authors.

The goal, instead, is to engage the reader so he/she never even entertains the possibility of tossing aside the book.

Here’s a quick-reference guide to writing effective dialogue in fiction.

Problem: What About Complete Sentences?

When I close my eyes, I can see my middle school English teacher, in a black broomstick skirt and print blouse, as she stressed the importance of “always writing in complete sentences.”

Any student hoping for a glowing report card would’ve taken the edict to heart. I started writing short stories in which the dialogue between characters read something like this:

“Good morning, James. It’s nice to see you again.”

“Thank you, Lisa, you as well. How have you been?”

“I’ve been very well lately, thank you, and you?”

Yawn.

Who talks like that?

Unless you’re writing dialogue in complete sentences for one character in your work of fiction, perhaps to emphasize a cultural difference or a high-class upbringing, few people really talk that way. What worked for Jane Austen in Pride and Prejudice isn’t going to fly with today’s readers.

Now what?

I’ll let you in on a secret. You’re going to have to disappoint your grade school English teacher.

Try an experiment. Go to a public place and eavesdrop. It helps maintain your cover if you’re not obvious about it, but just listen to the flow of conversation around you. You’re likely to hear snippets:

“Hey, man.”

“No.”

“Shut up.”

“Get lost, will you?”

“Pregnant? Julie?”

“I can’t— no, I don’t feel—”

Not many of these are complete sentences, by grammatical standards. Where are the subjects and the predicates? Could you diagram these examples?

Sure—they’re called words and phrases, and they’re what people generally use in conversation.

It’s not a crime to use a complete sentence—“Get away from me, Jim, before I call the police”—but opportunities don’t come up very often. Dialogue will flow and read more naturally on the page if you train yourself to write the way you hear people around you speaking.

Problem: Punctuating Dialogue

Periods, commas, ellipses, quotation marks, tigers, bears … you get the idea.

Don’t panic. Punctuating dialogue doesn’t have to be complicated, and your editor and proofreader will thank you for putting in the extra effort.

Here’s what you need to know about the most common punctuation in dialogue:

- When dialogue ends with a period, question mark, or exclamation mark, put the punctuation inside the quotation mark:

“Sam came by to see you.”

“Come home with me?”

“I hate you!”

- When punctuating dialogue with commas and an attribution before the dialogue, the comma goes after the attribution, and the appropriate punctuation mark goes inside the quotation mark at the end of the dialogue:

Mom said, “Sam came by to see you.”

- When punctuating dialogue with commas and adding an attribution after the dialogue, the comma goes inside the quotation mark:

“She came home with me,” Will said.

- When you’re punctuating dialogue with commas and adding a pronoun attribution, the comma goes inside the quotation mark, and the pronoun is not capitalized:

“I hate you,” she said.

- With dialogue that trails away, as though the speaker has gotten distracted, use an ellipsis inside the quotation mark:

“I just don’t know …” Jenny said.

- When dialogue is abruptly interrupted or cut off, use an em-dash inside the quotation mark:

“Well, I don’t think—”

“Because you never think!”

- For a non-dialogue beat to break up a line of dialogue, use either commas or em-dashes:

“And then I realized,” Jane said with a sigh, “that he lied to me.”

“Without the antidote”—Matt shook his head—“I don’t think we can save him.”

- When the speaker has started to say one thing, and changed his or her mind to say something else, use the em-dash:

“I don’t want to—I mean, I won’t hurt her.”

Note that semicolons and colons are rarely used in most contemporary fiction. They tend to appear too academic on the page, and if you use one or the other, or both, you run the risk of reminding the reader that they’re reading a story. Try not to do anything that breaks that fourth wall and calls attention to the mechanics of the story itself.

Look for the discussion about the great debate between “said” and other attributions in Part II of this post.

Questions

What “rules” about dialogue do you remember from grade school, writing conferences, classes, workshops, or books? Which rules drive you crazy? Which ones do you find yourself struggling to solve? How have you tackled those frustrations? Share your wisdom so others can benefit—writing takes a community to succeed!

* * * * *

Eleanore D. Trupkiewicz is an author, poet, blogger, book reviewer, and freelance editor and proofreader. She writes full-length thrillers as well as short stories, flash fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction. Her blogs are Engraved: All About Writing (http://eleanoretrupkiewicz.blogspot.com) and Daily Poetry Prompts (http://dailypoetryprompts.blogspot.com) and you can find her on one of her websites at www.eleanoretrupkiewicz.com or Refiner’s Fire Editing (www.refinersfireediting.com). Follow her on Twitter: @ETrupkiewicz. She lives and writes in Colorado with cats, chocolate, and assorted houseplants in various stages of demise.

Today, I’d like to answer a question from a reader.

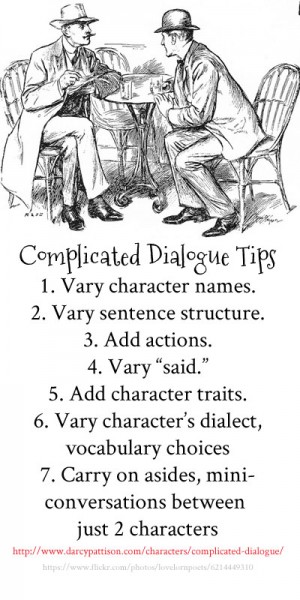

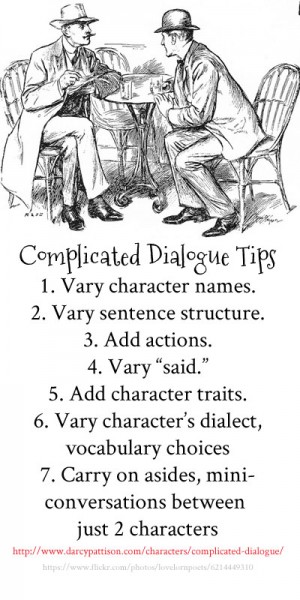

Shena asks, “I’m writing a story and I have five people who are carrying on a conversation with each other. How do I go about stating each person’s line without constantly using, he said, he replied or using the person’s name to say this person said after the sentence without it being an overkill of redundancy?”

Thanks for the question! You’re right to be concerned about repeating speech tags too often. It’s really a balancing act: on one hand, you don’t want to repeat too often, but neither do you want the reader to get lost. You have limited options, however, and you’ll have to work hard to keep this conversation interesting.

Speech Tags

Speech tags are the “he said” and “she said” that often accompanies dialogue. Notice that when you use HE or SHE, they are pronouns and will refer to the person immediately preceding. That’s important. The pronoun antecedent must be the right person. In the case of five people talking, you’ll probably need to use the character’s name often.\

James said, “Get lost.”

Jim said, “No way?”

Jill said, “Why?”

In the example above, notice that the job is even harder when character’s names all start with the same letter. Make sure your novel is populated with characters who have unique names that stand in contrast to one another. Not Jill and Bill, because they rhyme. Not James, Jim and Jill because they all begin with the same letter and are all one syllable. Instead, choose something like this: James, Brianna, Marguerite, Ally, and Bob.

Actions in the Midst of Dialogue

Dialogue rarely stands alone, though. When you add actions to dialogue, it’s sometimes called beats. This isn’t the same as action beats in a scene, but instead just means the small actions that are interwoven with dialogue. Sometimes those are the same, but sometimes not.

Dialogue beats are the small actions. Scenes demand actions, not just interior thoughts. What are your characters doing? Changing a light bulb.

James took the light hub out of the package and said, “Get lost.”

Reaching in, Marguerite gently took the package from him and said, “No way.”

Ally stuck out her lip in a pout. “Why?”

Notice here that Ally has an action, but has no speech tag. Sometimes, you can just omit the speech tag, if a character does something right before or after the dialogue and it’s clear that it’s this character speaking.

This still sounds boring, though. Part of that is because we repeated the structure too exactly in the first two sentences. They have an “action and said,” structure, which doesn’t really work here. Vary the structure of your sentences, sometimes putting the dialogue first, last, or even in the middle of the action.

Bob shook his head in disgust.

James tore open the light bulb package and snarled, “Get lost.”

“No way.” Marguerite’s voice was soothing and gentle. She took the torn cardboard from James and patted his shoulder.

Ally stuck out her lip in a pout. “Why should I get lost?” She hesitated and added, “I don’t want to.”

Bob grunted, “Why? Isn’t it obvious?”

“James is just upset,” Brianna said, “But that doesn’t mean he should get his way.”

Notice the variety here.

- There are some actions without dialogue.

- Dialogue occurs at the end, the beginning or the middle of the dialogue.

- After some dialogue, there’s a longer section of actions.

- I’ve used two substitutes for “said”: snarled and grunted. I don’t like using very many substitutes. Many writers explain that “said” disappears and readers don’t notice it. If you use an alternate word, it should add something important to the story.

Character Tics and Tags

Finally, it’s possible to use character tics or tags to good effect. Perhaps, poor Ally stutters. And James has a high pitched voice.

Bob shook his head in disgust.

James tore open the light bulb package and whined in soprano, “Get lost.”

“No way.” Marguerite’s voice was soothing and gentle. She took the torn cardboard from James and patted his shoulder.

Ally stuck out her lip in a pout. “W-w-why should I get lost?”

“Especially you!” James squeaked.

“W-w-why?”

Bob threw up his hands. “Why? Isn’t it obvious?”

“James is just upset,” Brianna said to Ally, “But that doesn’t mean he should get his way.”

You can start to see how dialogue can be enliveded with actions, sentence variety and small characterizations. You can devise many more ways to distinguish one character from another and use those traits in creating interesting dialogue. Try varying the character’s typical word choices or dialect. Within a larger conversation, too, you might have one character addressing another, as in Brianna’s aside to Ally and Marguerite’s intimate moment with James.

What’s your favorite way to keep complicated dialogue straight, yet keep enough variety to be interesting?

By: Genevieve Petrillo,

on 3/1/2014

Blog:

Cupcake Speaks

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

kidlit,

reading,

poetry,

writing,

children's literature,

characters,

ideas,

dialogue,

rejection,

picture book writing,

inspirational quote,

12x12,

Add a tag

Today is Dr. Seuss’s birthday. He would’ve been 109 years old. He is the Best Doctor Ever on account of no needles, no looking into ears with a flashlight, no sticks stuck into forbidden places, and no touching of my bits and pieces.

Waiting for the Doctor. Hoping for the Best.

Mom also loves Dr. Seuss for a million other reasons – his wild imagination, his silly rhyming, his crazy stories, and the fact that his first book was rejected 27 times before anybody said they liked it. Misery loves company.

Mom’s #1 favorite Dr. Seuss book is The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins from 1938.

Normally, Mom and I steer clear of anything that smacks of numbers, but counting those hats is so much fun and so suspenseful that we can’t resist it. Also, a hundred years ago, Mom’s 5th grade teacher, Mrs. Nelson read that story to her class and Mom and her friends giggled and counted and were afraid for poor little Bartholomew not being able to take his hat off for the king.

As of Dr. Seuss’s birthday, Mom is up to date on her 12×12 Challenge. She has written 2 new stories in the past 2 months. Now it’s a new month and time to start a new story.

In which direction should she go?

Direction? Up, of course.

King of the Hill of Filth

What will be original?

Original? It doesn’t get any more original than an old dog learning a new trick.

Who will step out of her list of character ideas?

Character? This one.

Or this one.

Or this one.

How will she make the story sparkle?

Sparkle? With a tiara, of course.

Am I sparkling, yet?

START YOUR NOVEL

Six Winning Steps Toward a Compelling Opening Line, Scene and Chapter

- 29 Plot Templates

- 2 Essential Writing Skills

- 100 Examples of Opening Lines

- 7 Weak Openings to Avoid

- 4 Strong Openings to Use

- 3 Assignments to Get Unstuck

- 7 Problems to Resolve

The Math adds up to one thing: a publishable manuscript.

Download a sample chapter on your Kindle.

Dialogue, what characters say, is an important element in any story.

DH, a reader here, is puzzled how to switch from one character to another.

Here’s an example she gave:

“Hey Danielle! Come check out this new book I got!” says Viola. “Okay just a sec.” says Danielle.

See, what I’m asking? I need to know what ways are there to talk between characters without having to say says Danielle, or says Viola or says Darcy.

Dialogue is what characters actually say and it is set off with quotes. Each time a character finishes talking and another begins, it is a new paragraph. If the character’s speech is a sentence, then it ends with a comma that goes inside the quote. If it is a question or exclamation point, that goes inside the quote instead of the comma. Generally, stories are told in past tense, so you would use “said” instead of “says,” which would be used for first person stories. And finally, I tend to put the character’s name before the said/says. In some ways this is a personal preference, but some references consider “said Viola” to be more juvenile than “Viola said.” Decide which you like and stick with it. It’s also a pet peeve for a character to constantly call the other person’s name. I don’t talk to people that way and characters shouldn’t either.

“Hey, come check out this new book I got!” Viola said.

“Okay, just a sec,” Danielle said.

That’s a good basic dialogue structure but now there are things that can help the story move along smoothly. First, is a beat or some sort of action. You can also insert the “she said” into the middle of the dialogue to vary the rhythm of the exchange.

Viola held up a shiny book. “Hey, come check this out!”

“Okay,” Danielle said. “Just a sec.”

Let’s add some setting.

From across the library, Viola held up a shiny book. “Hey!” she called in a stage whisper. “Come check this out!”

“Okay.” Danielle shoved back her chair and said, “Just a sec.”

It is also important to distinguish each character simply by the way they say something.

Viola: Hey, come check this out!

What are some possible responses for Danielle?

“Sure thing.”

“Why? Boring.”

“Girl, you know I don’t like books.”

“I’m busy.”

“Not now.”

“Go away.”

(Silence. She ignores Viola)

“Be quiet.”

Which one would THIS Danielle be most likely to say? It’s a matter of character. What is her attitude about reading and books and being in a library? What is her emotional state? Is she mad, sad, bored, or engrossed in a book of her own? All of those things will infuse the dialogue with something unique. And the reader should be able to tell Danielle’s voice from Viola’s. Because you also know all that about Viola and that should be in what she says and how she says it.

From across the library, Viola waved the new Harry Potter book. “It’s here! Come check it out.”

“Okay.” Danielle yawned, then put down her worn copy of Pride and Prejudice. “I’m coming.”

Dialogue must do more than just have people talking. It must also characterize and show attitude and move the story along. It’s worth the time it takes to explore options.

By:

Darcy Pattison,

on 7/3/2013

Blog:

Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

novel revision,

fiction techniques,

fiction,

plot,

characterization,

dialogue,

scenes,

mood,

creative nonfiction,

Add a tag

START YOUR NOVEL

Six Winning Steps Toward a Compelling Opening Line, Scene and Chapter

- 29 Plot Templates

- 2 Essential Writing Skills

- 100 Examples of Opening Lines

- 7 Weak Openings to Avoid

- 4 Strong Openings to Use

- 3 Assignments to Get Unstuck

- 7 Problems to Resolve

The Math adds up to one thing: a publishable manuscript.

Download a sample chapter on your Kindle.

All those fiction techniques you’ve spent time mastering — dialogue, description, setting, mood, scenes, characterization, and plot — are equally useful in writing nonfiction. Yes, there is more leeway in nonfiction than in the last twenty-five years, but publishers still value creative nonfiction or fiction written with fiction techniques.

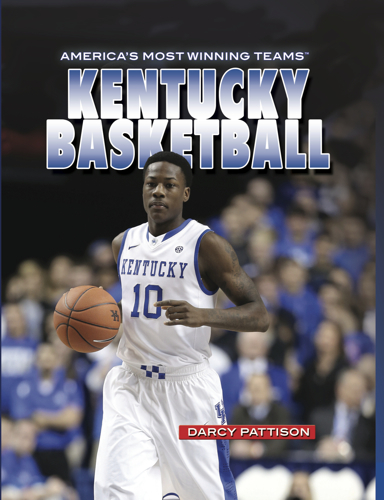

For example, I have a new nonfiction coming out next year, Kentucky Basketball: America’s Winningest Teams (Rosen, 2014). I searched and searched for an interesting opening to the story, until I found a scene that was worthy of describing.

It was Valentine’s Day, 1938. Packed into the University of Kentucky Alumni Gym were over 4000 people, some sitting in windows, others literally hanging from the rafters. The UK Wildcat basketball team led top-ranked Marquette University team by 10 points.

It’s an exciting rivalry game, early in the history of the basketball program at Kentucky. Fiction techniques dictated that I set the scene immediately. Then I use sensory details to fill in the scene to describe the fast-paced last few minutes. Joe “Red” Hagan shoots a long 49-foot field goal from near the half-court line. When Marquette missed three more times, it becomes the winning score. Then, the interesting part started. In the audience was “Happy” Chandler, governor of Kentucky. He was so excited by the win, and especially Red’s winning shot, that he called for a hammer and nail. He rushed onto the court and at the spot from which Red shot, Chandler hammered a nail into the floor to commemorate the moment.

It’s stuff of legends. And it deserved a full scene, which meant fiction techniques.

Research Details for NonFiction: Think Fiction

This means that while I was researching the nonfiction topic of Kentucky basketball, I was really looking for a certain type of information.

Scenes. I look specifically for scenes with a beginning, middle with conflict, and ending. It needs to be something fun and interesting, a specific event.

Details. Next, I look for details. Here’s a fact: the basketball arena was meant to seat 2500, but 4000 fans were in attendance. A newspaper article of the times specifically said that fans were literally sitting in windows and hanging from the rafters. I look for numbers, colors, sizes, shapes, extended descriptions, and other specific details. These will all help the story come alive.

Timelines. The timeline of the basketball game was important to lay out and newspaper reports were helpful. The details of the first half were important to understand, so I could focus on the last three minutes.

Personalities or Characters. This story is made richer by the presence of Happy Chandler, governor of Kentucky. What a happy thing that he was named Happy! It added to the appeal of the story that the governor with such a nickname was so Happy that he did something unexpected.

Unexpected. The story is interested because of the governor’s unexpected reaction. Stories of last-minute wins are commonplace, even if in the moment it feels like a miracle. By itself, Red Hagan’s shot isn’t remarkable enough to include in a book like this. But add to that the unexpected hammer and nail, and it becomes a remarkable story of a fan who wanted to acknowledge a miraculous shot. That’s why this story made it into the book’s introduction, surprise.

Research and document all your research; but while you’re researching, think fiction techniques. And your nonfiction article will become an interesting story that both informs and entertains.

Your characters enter a scene. Something happens, preferably conflict. Now, stop and ask yourself, "What primed the pump?"

Hopefully one conflict scene leads to another conflict scene, but what if you are moving from one POV character to another or a great deal of time has elapsed in between scenes?

After you write a scene, take another look at it and consider what primed the pump. No one enters a situation as a blank canvas.

1) What was Dick doing or feeling immediately prior?

It may be obvious if Dick is moving between consecutive scenes. Whatever happened in Scene 3 primes Scene 4. A plot hole occurs when something happens in scene 3 and is never addressed again. You don’t have to waste a lot of page time explaining what happened in between if it isn’t essential. However, if Dick was upset in Scene 3 and is perfectly calm when we see him again in Scene 7, then something happened to diffuse his mood. You should probably reference it with a line of dialogue or interiority during the opening transition paragraph of the new scene.

2) What is each character’s mindset as the scene progresses?

Every character entering a scene has thoughts and feelings. Are they having a good day or bad day? It affects their receptiveness. Whatever happened in prior scenes could have bearing on the current scene. Conflicting emotions and situations prime the conflict pump. If Jane is happy and Dick is angry, they could trade moods quickly.

3) Has your scene been properly set up?

Have you brought up an important point that you let lapse? Are the characters conflicted over something that makes no sense because you forgot to mention it in a previous scene? You may have cause and effect plot holes. If so, you have some revision to do. Beta readers or critique partners can be invaluable in catching these. My groups calls it the "read the book in my head, not the one on paper" syndrome.

4) Where does your scene take place? Why?

Settings are often bland and add nothing. You add value when you set the scene in a place that heightens tension. It has to be logical and organic. Don’t do it because “the script called for it.” If your couple is having an argument at home in the kitchen, it is realistic but is it interesting? Is the kitchen the best place for the argument? Can you make the setting more awkward for them? Say, a PTA meeting or on a crowded bus ride home?

5) Who is present?

You can have intense dialogue between two characters while they are alone. You add tension when they are striving to not be overheard or are wearing forced smiles at a formal function surrounded by family or coworkers. When two people are focused on each other, the crowd has a way of disappearing. They sometimes forget that other ears are listening. Being overheard can create future conflict. Having to behave decorously can force them to resume the conversation at another time, thus priming the pump for a future scene.

Consider not only the timeline of your story but how the timeline of the conflicts prime the pump. What happens immediately before can be as important as what happens during and immediately after.

.png.jpg?picon=4257)

By: Diana Hurwitz,

on 6/7/2013

Blog:

Game On! Creating Character Conflict

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

conflict,

writing,

characters,

plot,

communication,

craft,

dialogue,

genre,

argument,

Add a tag

There was a point in a work I was critiquing where a character completely changed her stance on the solution to the story problem without intervening scenes showing how or why. This is not the kind of plot twist you want to offer your reader. A good plot twist is set up long before it happens.

Let’s take a stroll back to beginning composition class to figure out how to illustrate a convincing change in character motivation.

When we first learned to write a paper, we had to come up with a thematic statement. We then came up with an outline listing key points to support or refute the thematic statement. Under each key point, we used paragraphs to expand each point.

How can you apply this to your plot?