new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Biology, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 50 of 130

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Biology in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: DanP,

on 10/1/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

science,

biology,

chemistry,

Oprah Winfrey,

DNA,

genes,

cells,

*Featured,

genomes,

HeLa,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

Henrietta Lacks,

life sciences,

Earth & Life Sciences,

genomics,

Biocode,

Dawn Field,

dna sequencing,

genomic sequencing,

The Double Helix with Dawn Field,

DNA database,

chromosones,

DNA research,

George Gey,

Add a tag

Society owes a debt to Henrietta Lacks. Modern life benefits from long-term access to a small sample of her cells that contained incredibly unusual DNA. As Rebecca Skloot reports in her best-selling book, “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks”, the story that unfolded after Lacks died at the age of 31 is one of injustice, tragedy, bravery, innovation and scientific discovery.

The post The woman who changed the world appeared first on OUPblog.

Science guy Bill Nye's book Undeniable is definitely a manifesto. He takes on Creationism and the deniers of evolution eloquently and successfully. But it's more. With Nye's easy style and wit, Undeniable both effectively explains and exalts the wonders of science and our evolved world. Books mentioned in this post Portland Noir (Akashic Noir) Kevin [...]

By: DanP,

on 9/3/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

science,

biology,

DNA testing,

terrorism,

human rights,

DNA,

ISIS,

genes,

Kuwait,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

genomes,

Science & Medicine,

life sciences,

Earth & Life Sciences,

Islamic state,

Biocode,

Dawn Field,

genome project,

The Double Helix with Dawn Field,

DNA database,

Add a tag

Kuwait is changing the playing field. In early July, just days after the June 26th deadly Imam Sadiq mosque bombing claimed by ISIS, Kuwait ruled to instate mandatory DNA-testing for all permanent residents. This is the first use of DNA testing at the national-level for security reasons, specifically as a counter-terrorism measure. An initial $400 million dollars is set aside for collecting the DNA profiles of all 1.3 million citizens and 2.9 million foreign residents

The post Kuwait’s war on ISIS and DNA appeared first on OUPblog.

Our free e-book for September:

Into Africa by Craig Packer

***

Craig Packer takes us into Africa for a journey of fifty-two days in the fall of 1991. But this is more than a tour of magnificent animals in an exotic, faraway place. A field biologist since 1972, Packer began his work studying primates at Gombe and then the lions of the Serengeti and the Ngorongoro Crater with his wife and colleague Anne Pusey. Here, he introduces us to the real world of fieldwork—initiating assistants to lion research in the Serengeti, helping a doctoral student collect data, collaborating with Jane Goodall on primate research.

As in the works of George Schaller and Cynthia Moss, Packer transports us to life in the field. He is addicted to this land—to the beauty of a male lion striding across the Serengeti plains, to the calls of a baboon troop through the rain forests of Gombe—and to understanding the animals that inhabit it. Through his vivid narration, we feel the dust and the bumps of the Arusha Road, smell the rosemary in the air at lunchtime on a Serengeti verandah, and hear the lyrics of the Grateful Dead playing off bootlegged tapes.

Into Africa also explores the social lives of the animals and the threats to their survival. Packer grapples with questions he has passionately tried to answer for more than two decades. Why do female lions raise their young in crèches? Why do male baboons move from troop to troop while male chimps band together? How can humans and animals continue to coexist in a world of diminishing resources? Immediate demands—logistical nightmares, political upheavals, physical exhaustion—yield to the larger inescapable issues of the interdependence of the land, the animals, and the people who inhabit it.

Download your free copy of Into Africa here.

By: JulieF,

on 8/13/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

biology,

climate change,

vaccination,

*Featured,

causation,

Science & Medicine,

herd immunity,

Earth & Life Sciences,

Ecological Society of America,

Stephen H. Jenkins,

Tools for Critical Thinking in Biology,

human thinking,

single cause versus multiple causes,

Add a tag

Imagine the thrill of discovering a new species of frog in a remote part of the Amazon. Scientists are motivated by the opportunity to make new discoveries like this, but also by a desire to understand how things work. It’s one thing to describe the communities of microorganisms in our guts, but quite another to learn what causes these communities to change and how these changes influence health.

The post Complexities of causation appeared first on OUPblog.

Tuesday, August 12th, is the inaugural “World Elephant Day,” initiated by a number of elephant conservation organizations, each working in collaboration toward “better protection for wild elephants, improving enforcement policies to prevent the illegal poaching and trade of ivory, conserving elephant habitats, better treatment for captive elephants and, when appropriate, reintroducing captive elephants into natural, protected sanctuaries.”

Caitlin O’Connell, the author of Elephant Don: The Politics of a Pachyderm Posse, recently posted at National Geographic about the loss of Greg, the iconic elephant whose rise and reign as a don among his peers was chronicled in her book. Finally reconciling that fact that she hadn’t seen Greg in four years with the increasing likelihood of his death inspired O’Connell to post a formal obit, of sorts, in which she reminisced on Greg’s presence, absence, and legacy. In part:

Four years after what most probably marked the passing of the don, I can’t ignore the impact that his absence has had on this male society, and just how similar their social dynamics have been to a human society after the loss of a great figure head. In 2012, the first season without the don, there seemed to be competing factions, Prince Charles leading one camp and Luke the other. The interesting thing in that dynamic was the fact that both these characters had been bullies and had previously shown no interest in taking the next generation under their elephantine wing. But in the absence of Greg, they both changed their tune and had amassed an impressive following. But by 2013, both of these building strongholds had collapsed with barely a trace of the loyal following they had built for themselves.

By 2014 it was hard to imagine that such a tightknit social group of male elephants existed. Long gone were the days of Greg’s conga line amassing on the horizon and coming in to spend hours together and the social club that was Mushara.

And now, here we are in the last quarter of the 2015 season, and there is barely a trace of the don’s social fabric that he has so carefully stitched together and vigorously maintained. It was hard for even me to remember the way things were.

A faculty member at the Stanford University School of Medicine, O’Connell has been chronicling the lives of African male elephants for the past twenty-three years, including Elephant Don and an earlier work, The Elephant’s Secret Sense, both of which are published by the University of Chicago Press. As one of our foremost experts on elephant behavior and communication, her posts for National Geographic‘s Voices blog are an excellent foray into the issues faced first-hand by these majestic creatures, as well as an anthropological chronicle of the day-to-day lives of a particular group of elephants living at Etosha National Park in Namibia. You can read more about Greg’s story in Elephant Don—in addition to her blog posts for NG and numerous popular books and articles about elephant communities, O’Connell runs a Tumblr, Elephant Skinny, filled with anecdotes and images that pick up where Elephant Don leaves off (most recently with the birth of Athena, daughter to Mona Lisa, pictured below).

To read more about World Elephant Day, click here.

To read more by Caitlin O’Connell, click here.

By: Sara Pinotti,

on 8/8/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

conference,

biology,

evolution,

ecology,

Europe,

*Featured,

Science & Medicine,

evolutionary biology,

Earth & Life Sciences,

eseb,

eseb 2015,

eseb15,

european society for evolutionary biology,

lausanne,

Leo Beukeboom,

lucy nash,

Nicolas Perrin,

The Evolution of Sex Determination,

Books,

Add a tag

My first experience of an academic conference as a biology books editor at Oxford University Press was of sitting in a ballroom in Ottawa in July 2012 listening to 3000 evolutionary biologists chanting ‘I’m a African’ while a rapper danced in front of a projection of Charles Darwin

The post Looking forward to ESEB 2015 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Hannah Paget,

on 7/30/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

*Featured,

Science & Medicine,

UKpophistory,

Earth & Life Sciences,

biology,

zoology,

Aristotle,

eighteenth-century,

animal vegetable mineral,

life sciences,

victorian britain,

Linnaeus,

Mrs Gren,

Susannah Gibson,

the natural world,

life,

school,

Education,

nature,

science,

Books,

History,

British,

Add a tag

Did you learn about Mrs Gren at school? She was a useful person to know when you wanted to remember that Movement, Respiration, Sensation, Growth, Reproduction, Excretion, and Nutrition were the defining signs of life. But did you ever wonder how accurate this classroom mnemonic really is, or where it comes from?

The post What is life? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Joe Hitchcock,

on 7/1/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

science,

Medical Mondays,

biology,

sound,

deafness,

hearing,

*Featured,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

auditory nerve,

auditory neuropathy,

aural,

Jos J. Eggermont,

selective hearing,

temporal processing disorder,

Add a tag

Imagine that your hearing sensitivity for pure tones is exquisite: not affected by the kind of damage that occurs through frequent exposure to loud music or other noises. Now imagine that, despite this, you have great problems in understanding speech, even in a quiet environment. This is what occurs if you have a temporal processing disorder

The post Hearing, but not understanding appeared first on OUPblog.

Bolder. More global. Risk-taking. The home of future stars.

Not a tagline for a well-placed index fund portfolio (thank G-d), but the crux of a piece by Sam Leith for the Guardian on the “crisis in non-fiction publishing”—ostensibly the result of copycat, smart-thinking, point-taking trade fodder that made Malcolm Gladwell not just a columnist, but a brand. As Leith asserts:

We have a flock of books arguing that the internet is either the answer to all our problems or the cause of them; we have scads of books telling us about the importance of mindfulness, or forgetfulness, or distraction, or stress. We have any number about what one recent press release called the “always topical” debate between science and religion. We have a whole subcategory that concern themselves with “what it means to be human.”

Enter the university presses. Though Leith acknowledges they’re still capable of producing academic jargon dressed-up in always already pantalettes, they are also home to deeper, more complex, and vital trade non-fiction that produces new scholarship and nuanced contributions to the world of ideas, while still targeting their offerings to the general reader. If big-house publishers produce brands, scholarly presses produce the sharp, intelligent, and individualized contributions that later (after, perhaps, some mutation and watering down by the conglomerates) establish their fields. Especially nice to see Yale, Harvard, Oxford, Princeton, Cambridge, and UCP called out for their “high-calibre, serious non-fiction of the quality and variety.”

More from the Guardian article:

In natural history and popular science, alone, for instance: Hal Whitehead and Luke Rendell’s amazing book The Cultural Lives of Whales and Dolphins or Brooke Borel’s history of the bedbug, Infested, or Caitlin O’Connell’s book on pachyderm behaviour, Elephant Don, or Christian Sardet’s gorgeous book Plankton? All are published by the University of Chicago. Beth Shapiro’s book on the science of de-extinction, How to Clone a Mammoth? Published by Princeton. In biography, Yale – who gave us Sue Prideaux’s award-winning life of Strindberg a couple of years back – have been quietly churning out the superb Jewish Lives series. Theirs is the new biography of Stalin applauded by one reviewer as “the pinnacle of scholarly knowledge on the subject”, and theirs the much-admired new life of Francis Barber, the freed slave named as Dr Johnson’s heir. Here are chewy, interesting subjects treated by writers of real authority but marketed in a popular way. The university presses are turning towards the public because with the big presses not taking these risks, the stuff’s there for the taking.

You can read more about the University of Chicago Press’s biological sciences list here. And the rest of our titles, organized by subject category, here. Follow the #ReadUP hashtag on Twitter for old and new books straddling the line between accessible scholarship and exciting nonfiction.

Kean's latest achievement, lauded as his best yet, is a book about neuroscience, but don't let that intimidate you. Anyone who enjoys reading popular science books will appreciate the easy-to-understand explanations and wonderfully engaging stories that highlight the history of this field. Books mentioned in this post The Tale of the Dueling... Sam Kean Sale [...]

Earlier this month, the New York Times revisited Paul R. Ehrlich—through both his cult favorite 1968 work The Population Bomb, and as a doomsday-advocating talk show guest, who spent much of the 1970s and years since advancing the notion that it was just a matter of time before the strained resources of our overcrowded planet could no support humanity. Though the years since might have seeded us with a kinder, gentler apocalypse, Ehrlich remains (mostly) resolute:

But Dr. Ehrlich, now 83, is not retreating from his bleak prophesies. He would not echo everything that he once wrote, he says. But his intention back then was to raise awareness of a menacing situation, he says, and he accomplished that. He remains convinced that doom lurks around the corner, not some distant prospect for the year 2525 and beyond. What he wrote in the 1960s was comparatively mild, he suggested, telling Retro Report: “My language would be even more apocalyptic today.”

And yet, in a second Times piece, an op-ed, “Paul Ehrlich’s Population Bomb Argument Was Right,” by statistics professor Paul A. Murtaugh, Ehrlich’s ideas are framed less as nostalgia for a time of reasonable doomsday bets, and more as the inevitable catastrophic consequences of human reproduction and environmental degradation, in the age of what the children are calling the Anthropocene:

The more catastrophic consequences of human population growth predicted by Paul Ehrlich have not yet materialized, in part because he did not anticipate the enormous increase in agricultural productivity enabled by fossil fuels. But Ehrlich’s population bomb will inevitably detonate when fossil fuels become too scarce and expensive to sustain a growing population. . . . Ehrlich’s argument that expanding human populations cannot be sustained on an Earth with finite carrying capacity is irrefutable and, indeed, almost tautological. The only uncertainty concerns the timing and severity of the rebalancing that must inevitably occur.

If this seems reasonable, Ehrlich writes about the current state of our environment, along with the continual threats posed by our often careless inhabitancy, in two recent books: Hope on Earth (a conversation with Michael Charles Tobias about catastrophe and morality within the contemporary context) and the forthcoming Killing the Koala and Poisoning the Prairie (a comparative study of how these concerns have been [mis]handled by two global democracies, Australia and the United States, coauthored with Corey J. A. Bradshaw). You can read more about both here.

By: Shannon Hazard,

on 6/11/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Journals,

genetics,

biology,

evolution,

q and a,

disease,

molecular,

epigenetics,

*Featured,

oxford journals,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

Earth & Life Sciences,

environmental epigenetics,

Michael Skinner,

Add a tag

Environmental Epigenetics is a new, international, peer-reviewed, fully open access journal, which publishes research in any area of science and medicine related to the field of epigenetics, with particular interest on environmental relevance. With the first issue scheduled to launch this summer, we found this to be the perfect time to speak with Dr. Michael K. […]

The post A Q&A with the Editor of Environmental Epigenetics appeared first on OUPblog.

Congratulations to George Monbiot, author of Feral: Rewilding the Land, the Sea, Human Life, which was just announced as the winner of the 2015 Orion Book Award for nonfiction, which honors “books that deepen the reader’s connection to the natural world, [and] represent excellence in writing.” In Feral, Monbiot, a journalist, columnist for the Guardian, and environmentalist (see his recent TED talk here), argues for a twenty-first-century movement based upon the concept of rewilding, which seeks to free nature from human intervention and allow ecosystems to resume their natural processes.

From a recent profile of the book at the Orion Blog:

When’s the last time you walked into the woods, or a park, or your garden, and felt unsure of what—or who—you might see? If the answer is “it’s been a while,” you’re not alone. With his intrepid and imaginative new book, Feral: Rewilding the Land, the Sea, and Human Life, journalist George Monbiot has invented a term for this twenty-first-century condition that afflicts so many of us in the developed world: “ecological boredom.” He’s come up with a prescription, too, which involves large-scale reintroductions of keystone species to the landscapes that humans have emptied out and made their own. If this sounds reckless and implausible, it’s not: Monbiot has done his research, and builds a case for how well his surprising list of animal recruits would fit into his home landscape of Britain. From moose and lynx to hippopotamuses and black rhinoceroses, Feral invites readers to imagine a wilder, less stifled and more primal world—one in which we humans can come to recognize our animal natures once again.—Scott Gast

And from the Orion editors’ commendation for the award:

George Monbiot’s well-researched book of narrative storytelling, speculation, and bold imagination is a vote in favor of rewilding not just nature but the human spirit. Feral invites readers to envision a wilder, less stifled and more primal world—one in which we humans can come to recognize our animal selves once again.

To read more about Feral, click here.

By: Suzie Eves,

on 6/8/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

orchids,

pollen,

wasps,

*Featured,

oxford journals,

sexual reproduction,

life sciences,

Earth & Life Sciences,

annals of botany,

Alun Salt,

aob,

fascination of plants,

sexual deception,

flowers,

Videos,

Journals,

nature,

science,

biology,

Multimedia,

botany,

insects,

Add a tag

“In the spring a young man's fancy lightly turns to thoughts of love” (Alfred, Lord Tennyson), but he could have said the same for insects too. Male insects will be following the scent of females, looking for a partner, but not every female is what she seems to be. It might look like the orchid is getting some unwanted attention in the video below, but it’s actually the bee that’s the victim. The orchid has released complex scents to fool the bee into thinking it’s meeting a female.

The post Sexual deception in orchids appeared first on OUPblog.

By: DanP,

on 6/4/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

genetics,

biology,

DNA,

genes,

*Featured,

genomes,

Science & Medicine,

science,

TED talks,

life sciences,

million genomes project,

million genomes,

personal genome project,

Earth & Life Sciences,

James Watson,

Biocode,

Dawn Field,

The Double Helix with Dawn Field,

billion genomes,

craig venter,

double helix,

jack horner,

Add a tag

One of the most fun and exciting sources of information available for free on the Internet are the videos found on the Technology, Entertainment and Design (TED) website. TED is a hub of stories about innovation, achievement and change, each artfully packaged into a short, highly accessible talk by an outstanding speaker. As of April 2015, the TED website boasts 1900+ videos from some of the most imminent individuals in the world. Selected speakers range from Bill Clinton and Al Gore to Bono and other global celebrities to a range of academics experts.

The post TED Talks and DNA appeared first on OUPblog.

An excerpt from Edible Memory: The Lure of Heirloom Tomatoes and Other Forgotten Foods by Jennifer A. Jordan

***

“Making Heirlooms”

How could anything as perishable as fruits and vegetables become an heirloom? Many things that are heirlooms today were once simple everyday objects. A quilt made of fabric scraps, a wooden bowl used in the last stages of making butter, both become heirlooms only as time increases between now and the era of their everyday use. Likewise, the Montafoner Braunvieh—a tawny, gorgeously crooked-horned cow that roams a handful of pastures and zoos in Europe, a tuft of hair like bangs above her big brown eyes—or the Ossabaw pigs that scurry around on spindly legs at Mount Vernon were not always “heirlooms.” Nor were the piles of multicolored tomatoes that periodically grace the cover of Martha Stewart Living magazine or the food pages of daily newspapers. What happened to change these plants and animals from everyday objects into something rare and precious, imbued with stories of the past? In fact, food has always been an heirloom in the sense of saving seeds, of passing down the food you eat to your children and your children’s children, in a mixture of the genetic code of a given food (a cow, a variety of wheat, a tomato), and also in handing down the techniques of cultivation, preservation, preparation, and even a taste for particular foods. It is only with the rise of industrial agriculture that this practice of treating food as a literal heirloom has disappeared in many parts of the world—and that is precisely when the heirloom label emerges. The chain is broken for many people as they flock to the cities and the number of farmers and gardeners declines. So the concept of an heirloom becomes possible only in the context of the loss of actual heirloom varieties, of increased urbanization and industrialization as fewer people grow their own food, or at least know the people who grow their food. These are global issues, relevant to hunger and security and to cultural memory, community, and place. This book addresses one aspect of the much larger spectrum of issues around culture and agricultural biodiversity, focusing on these old seeds and trees.

In some ways heirlooms become possible (as a concept) only because of the industrialization and standardization of agriculture. They went away, there was a cultural and agricultural break, placing temporal and practical distance between current generations and past foods. In the meantime, gardeners and farmers quietly saved seeds for their own use. And then, as I discuss in much greater detail below, these heirloom foods began, tomato by tomato, apple by apple, to return to some degree of popularity.

In the United States, newspaper article after article, activist after activist, describes heirloom varieties as something one’s grandmother might have eaten. The implication is that there has been a significant break—that the current generation and their parents lost touch with these fruits, vegetables, and animals but that their grandparents might not have. “Heirlooms are major-league hot,” a reporter marveled in 1995. “As we become more of a technological society, people are reaching into the garden to get back that simple life, the simple life of their grandparents.” Concepts like “old-fashioned,” “just like Grandma ate,” and even “heirloom” can feel very American. But this is a mythical grandmother. The grandmothers of today’s United States are a diverse crew whose cooking habits are just one of the ways they differ. Gender is also obviously a vital element of the study of food production and consumption. Women are perceived as (and often are) the primary cooks and shoppers, and there are many gendered understandings of our relationships to food. Many people, men and women alike, have little time to cook, despite recent exhortations to engage in more home cooking. My own grandmother (the niece of my great-great-aunt Budder whom I write about in the prologue) smoked cigarettes and drank martinis with gusto, and for her, making Christmas cookies consisted of melting peanut butter and butterscotch chips, stirring in cornflakes, and forming the mixture into little clumps that would harden as they cooled. I loved them as a child, and when I make them today, I am invoking my grandmother just as much as other people may when serving up a platter of ancestral heirloom tomatoes.

In the context of food, however, the word “heirloom” also has a genetic connotation. The object itself is not handed down. Heirloom tomatoes are either eaten or they rot. Old-fashioned breeds of pigs are slaughtered and end up as pork chops; they rarely live a long life like Wilbur in Charlotte’s Web, without the help of a literate spider and a film career. The “heirloom,” then, what is handed down, is the genetic code. Heirloom foods are products of human intervention, ranging from selecting what seeds to save for the next growing season to deciding which tom turkey should father poults with which hen.

The genetic heirloom takes on a physical expression in the form of a pig or a tomato, for example, to which people may then attach all kinds of meanings—not only the physical appetite for the flavor of a particular tomato or pork chop, but also the sense that edible heirlooms connect us to something many people see as more authentic than supermarket fare. Over and over, in conversations and newspaper articles, orchards and public lectures, I have heard people articulating a search for a connection to the past, even as they also sought out appealing flavors, colors, and textures. The appetite for an heirloom food commonly leads, of course, to the destruction of its embodiment—in a Caprese salad, say, or an apple pie—but it is precisely the consumption of its phenotype that ensures the survival of the genetic code that gave rise to it.

A guide to heirloom vegetables describes heirloom status (of tomatoes and other produce) in three ways:

- The variety must be able to reproduce itself from seed [except those propagated through roots or cuttings]. . . .

- The variety must have been introduced more than 50 years ago. Fifty years, is, admittedly, an arbitrary cutoff date, and different people use different dates. . . . A few people use an even stricter definition, considering heirlooms to be only those varieties developed and preserved outside the commercial seed trade. . . .

- The variety must have a history of its own.

The term “heirloom” itself generally applies to varieties that are capable of being pollen fertilized and that existed before the 1940s, when industrial farming spread in North America and the variety of species grown commercially was significantly reduced. Generally speaking, an heirloom can reproduce itself from seed, meaning seed saved from the previous year. When growing hybrids, you have to buy new seed each year (for plants that reproduce true to seed; apples, potatoes, and some other fruits and vegetables are preserved and propagated through grafts or cuttings rather than seeds). In other words, if you save the seeds of a hybrid tomato and plant them the next year, you more than likely won’t be pleased with what you get, if you get anything at all. Furthermore, simply because they are “heirloom” tomatoes does not mean they are native. In fact, tomatoes are native not to the United States, but to South and Central America, and many heirloom varieties such as the Caspian Pink were developed in Russia and other far-off places. People also use the term “heirloom” to describe old varieties of roses, ornamental plants, fruit trees (reproduced by grafting rather than from seed), potatoes, and even livestock.

As the US Department of Agriculture’s heirloom vegetable guide explains, “Dating to the early 20th C. and before, many [heirloom varieties] originated during a very different agricultural age—when localized and subsistence-based food economies flourished, when waves of immigrant farmers and gardeners brought cherished seeds and plants to this country, and before seed saving had dwindled to a ‘lost art’ among most North American farmers and gardeners.” Fashions, tastes, and technology changed, but “since the 1970s, an expanding popular movement dedicated to perpetuating and distributing these garden classics has emerged among home gardeners and small-scale growers, with interest and endorsement from scientists, historians, environmentalists, and consumers.” In Germany they speak of alte Sorten, “old varieties,” but this phrasing does not carry the same symbolic, nostalgic weight as the homey word “heirloom.” In French heirloom varieties may be called légumes oubliés, “forgotten vegetables,” or légumes anciennes. Of course, once vegetables are labeled forgotten, they’re not really forgotten anymore. In general, the United States has a different relationship to its past than European countries do. Thus there are regional gardening and cooking traditions in the United States, as well as a particular form of nostalgia that allows the term “heirloom” to apply to fruits, vegetables, and animals in the first place. The idea of an heirloom object can be very homespun. Certainly an heirloom can be something of great monetary value, but it can also be a threadbare quilt, a grandfather’s toolbox, or in my case the worn and mismatched paddles my great-great-aunt used in the last stages of making butter. The word “heirloom” can be a way to preserve biodiversity, but it can also be inaccurate and misused, a label slapped on an overpriced tomato. There is always the danger that dishonest grocers and restaurateurs will exploit the desire for local, seasonal, and heirloom food.

Heirlooms of all sorts are often wrapped up in nostalgic ideas about the past. Patchwork quilts and butter churns evoke not only idyllic images of yesteryear, but often difficult lives circumscribed by poverty and dire necessity as much as by simplicity and self-sufficiency. They speak of times (and, when we think globally, of places) when life may have been (or may still be) not only technologically simpler but also much, much harder. Old-fashioned farm implements in the front yards of rural Wisconsin, or in living history museums, evoke nostalgic feelings. But there’s a reason they’re in museums or front yards and not hitched to a team of horses or in the hands of a farmer, at least in Wisconsin. These are backbreaking tools whose functions have wherever possible been transferred to machines.

Even today, while it may surprise people who pick up a book like this, when I first tell someone about my work, I routinely have to explain what an heirloom tomato is. On a recent trip to a Milwaukee farmers’ market, I heard an older man say to his female companion, “Heirloom tomatoes? Never heard of ’em.” He’s not alone. While some food writers and restaurant reviewers may feel that heirloom tomatoes are yesterday’s news, plenty of consumers are still encountering them for the first time.

Heirloom varieties are just one form of edible memory, but they offer a unique opportunity to understand the powerful ways memory and materiality interact, and how the stories we tell one another about the past shape the world we inhabit. I write about heirlooms not because I think they’re the only way to go, but because they present an intriguing sociological puzzle (How can something as perishable as a tomato become an heirloom?) and because they are the subject of so much activity by so many different people. These efforts, all this work, are also just the latest turn in the twisting path of fruit and vegetable trends, of the relationship of these plants to human communities. This book recounts my search for endangered squashes, nearly forgotten plums, and other rare genes surviving in barnyards, gardens, and orchards, this intertwining of botanical, social, and edible worlds.

Investigating Heirlooms

I relish the moments I have spent with the old-fashioned farm animals at the Vienna zoo, standing in the stall with the zookeeper to scratch the fluffy head of a newborn lamb or the vast forehead of that speckled black-and-white cow, one of only a few of her breed remaining on the planet, who had just dutifully produced a calf that looked exactly like her. I also relish the meals I’ve prepared from multicolored potatoes or tomatoes; and, given a free Saturday, I can spend hours at farmers’ markets, contemplating what I can do with a bucket of almost overripe peaches (freeze them for my winter oatmeal) or a pile of striped squash (a spectacularly failed attempt at whole wheat squash gnocchi, which may still be lurking in the back of my freezer). And I have my own history of deep attachment to processed spice cake and the unctuous taste of a rare glass of whole milk—a reminder that “edible memory” goes far beyond the relatively narrow confines of heirloom food.

But I am also a sociologist, so in this book, while I am fond of many of the places, people, and foods I discuss, I also aim, ultimately, to tell a sociological story. I did not, like Barbara Kingsolver in Animal, Vegetable, Miracle, try to raise turkeys or can a heroic quantity of heirloom tomatoes. Unlike Michael Pollan in the journey he undertook for The Omnivore’s Dilemma, I did not try to shoot anything or make my own salt. Along the way, however, I did get involved; I immersed myself in these rich landscapes, markets, and texts and in conversations with diverse groups and individuals who often, unknown to anyone else, managed to hold on to vital and beautiful collections of genes in the form of old apple trees or tomato seeds, turnips or taro. I set out not to grow these plants and raise these animals myself, but to talk with and observe the diverse and committed gardeners, farmers, curators, seed savers, animal breeders, and other people who make possible the persistence of these plants and animals on this planet. I set out to understand in particular where these plants have come from, the threats they face, the kinds of places that are created in the attempt to save them, and the stories they tell us about the past and about ourselves, as well as how they figure in the broader patterns of human appetites, trends and fashions, habits and intentions.

The research for this book comprised seven years of observation and analysis. In my efforts to understand how tomatoes became heirlooms and apples became antiques, I set out on multiple journeys, of varying sorts. I drove down Lake Shore Drive to the Green City Market and urban farms and gardens in Chicago, traveled across town in Milwaukee to Growing Power and other urban growers, flew across the Atlantic to Vienna, took a streetcar over the bridges of Stockholm to get to the barnyards and gardens of the Swedish national open-air folk museum, and got lost on the tangle of bridges and highways between Washington, DC, and rural Virginia in search of Thomas Jefferson’s vegetable garden and George Washington’s turkeys. I also took more philosophical journeys: literary and archival travels through the pages of government reports, scholarly periodicals, and popular and scientific books. I traveled through recipe collections and the glossy pages of food magazines, through the digital universe of online databases, and through correspondence with colleagues and informants in far-off places. The collection of these journeys, of this movement through gardens, barnyards, orchards, and markets, as well as thickets of printed and digital information, accounts for the story I tell here.

This book emerged in part from solitary hours in front of the computer, taking notes, with stacks of books at my side, reading newspaper articles and academic journal articles on everything from apple grafting to patent law. I analyzed thousands of newspaper articles, charting the emergence of the term “heirloom” in popular food writing and looking for changes in the quantity and quality of the discussion over time as well as differences and similarities across different kinds of foods. Much of this book is based on the ways heirloom varieties register in public discussions, especially the media, and the ways they get taken up by organizations and individuals, both in and out of the limelight. Blogs and other food writing have also figured centrally in my analysis of the heirloom food movement as markers of popular discussions, and I have relied on hundreds of secondary sources (see the bibliography) for historical information about specific foods. I read encyclopedias and fascinating scholarly and popular books, charting the rise and fall of particular foods and their historical transformations. And I drew on the insights of my colleagues in sociology and neighboring academic disciplines and the ways they think about things like culture, memory, and food.

Occasionally I would take a break and cook one of the recipes I came across, and I also left my desk and set out to visit the farms and gardens, camera and notebook in hand. I scratched the noses of wiry old pigs, walked through fragrant herb gardens, and tasted hard cider and fresh bread, the hems of my jeans coated in mud and my nose sunburned from a long day in an Alpine valley or at a midwestern heirloom seed festival. I spoke formally and informally with gardeners, farmers, and chefs, activists, seed savers, academics, and all kinds of people devoted to food. I visited farms and gardens and living history museums and farmers’ markets, and I attended conferences and public lectures and delivered some of my own to smart crowds full of eager gardeners, eaters, and thinkers. I also spoke with the gardeners of less well-known historical kitchen gardens across Europe and the United States, quiet conversations about their enthusiasm for their work and about their assessments of the changing public perceptions of edible biodiversity over recent decades. Many of these farmers and gardeners became good friends, and our late-night conversations over good meals in my dining room or cheap beer at a rooftop farm in Chicago’s Back of the Yards also came to shape my sociological understanding of these trends. Sifting through the stacks of papers on my desk in the depths of winter, and wandering through gardens, barnyards, and farmers’ markets in the heat of summer, I wanted to see what patterns I might find.

Finding Edible Memory

What I found was something I came to call “edible memory.” And I want to emphasize that I did not expect to find it. Edible memory emerged out of these documents, landscapes, and conversations. This book focuses largely on the contemporary United States, with occasional examples drawn from elsewhere. But the fundamental ideas and questions can help us to think about other times and places as well. For sociologists, the study of human behavior— of what people actually do, and do in large enough numbers to register as visible patterns—is at the heart of our work. Many of us are studying what happens when people are highly motivated, when they are so passionate about something that the passion provokes action. That said, many of us are also deeply interested in the small actions of habit, the little steps we take every day that add up to this big thing called society. What we eat for breakfast, who we spend time with and how, what we buy, even what we ignore— these are all crucial to understanding how and why things are as they are. This book is about the fervent devotees, the people who can’t not plant orchards full of apple trees or spend countless hours saving turnip seeds. But it is also about the ways millions (perhaps even billions) of people make small decisions every day about what to serve their families, about how to feed themselves.

When I began to look in scholarly and popular writing, and in kitchens, gardens, farms, and markets, I saw more and more evidence of edible memory: in the rice described by geographer Judith Carney, in the gardens of Hmong refugees in Minnesota, in the hard-won community gardens of New York’s Lower East Side, and in the appetites and memories of friends and strangers alike. Edible memory appears in the reverberations of African foods in a range of North American culinary traditions, in the efforts to cultivate Native American foods today, in the shifting appetites of immigrant populations and ardently trendy folks in Brooklyn or Portland. It goes far beyond the heirloom, but heirlooms were my way in, a way to narrow, at least temporarily, the scope of the investigation and to explore one particularly potent intersection of food, biodiversity, and tales of past ways of being. Edible memory is a widely applicable concept, and I hope it will resonate well beyond the boundaries of the examples I have included in this book.

Edible memory is also in no way the sole province of elites. Much of what people understand as heirloom food today is expensive and out of reach, justifying the pretensions sometimes assigned to heirloom tomatoes, farmers’ markets, or the pedigreed chicken in the television show Portlandia. Food deserts, double shifts, cumbersome or expensive transportation, and straight-up poverty greatly reduce access to a wide range of foods, heirlooms included. But to assume that edible memory is strictly connected to privilege ignores the vital connections people have to food at a range of locations on the socioeconomic scale. Poverty, and even hunger, does not preclude (and indeed may intensify) the meanings and memories surrounding food. As many researchers have discussed, the various alternative approaches to food— heirlooms, but also farmers’ markets, organic and local foods, and artisanal foods—tend to be expensive, eaten largely by elites—well-off and often white. However, while that may characterize what we might call mainstream alternative, both edible biodiversity and edible memory happen across the socioeconomic spectrum. There are vibrant, successful projects in which people worlds away from expensive restaurants and farmers’ markets grow and eat many of the same kinds of memorable vegetables, in rural backyards, small urban allotments, and school gardens. Chicago alone is home to many farms and gardens supplying food and often employment and other projects in low-income communities, projects like the Chicago Farmworks, Growing Home, Gingko Gardens, or the Chicago location of Growing Power, which is even selling its produce in local Walgreens, trying to improve access to locally grown produce in predominantly low-income and African American neighborhoods. The numerous farms and gardens profiled on Natasha Bowen’s blog and multimedia project, The Color of Food, also offer examples across the country of farmers and gardeners with a deep commitment to many of the same foods that find their way into high-priced grocery stores or expensive restaurant dinners.

At the same time, I do not want to argue that edible memory is a universal concept. We can ask where and how it appears and matters, but we should not assume that it is everywhere either present or significant. It is certainly widespread, based on the research I have conducted, but it is not universal. For some people food may be a way to imagine communities, to understand their place in the world and connect to other people, but for others it is simply physical sustenance or transitory pleasure.

To read more about Edible Memory, click here.

By: Hannah Paget,

on 5/14/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

women,

Sociology,

science,

biology,

male,

Power,

female,

risk,

competitive,

aggression,

human behaviour,

*Featured,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

Psychology & Neuroscience,

hormone,

Joe Herbert,

male behaviour.,

sexes,

testosterone,

will to win,

Add a tag

A red open car blasts past you, exhaust and radio blaring, going at least 10 miles faster than the speed limit. Want to take a bet on the driver? Well, you won’t get odds. Everyone knows the answer. All that exhibitionism shouts out the commonplace, if not always welcome, features of young males. Just rampant testosterone, you might say. And that’s right. It is testosterone. The young man may be driving the car but testosterone is what’s driving him.

The post Sex, cars, and the power of testosterone appeared first on OUPblog.

By: DanP,

on 5/7/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Biocode,

Dawn Field,

design dna,

DNA nanobots,

DNA origami,

dna sequencing,

dna tags,

genomic sequencing,

George Church,

helix bridge,

herring sperm,

the double helix,

uses of DNA,

Books,

science,

biology,

DNA,

earth sciences,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

molecules,

genomes,

Science & Medicine,

life sciences,

Earth & Life Sciences,

Add a tag

DNA is the foundation of life. It codes the instructions for the creation of all life on Earth. Scientists are now reading the autobiographies of organisms across the Tree of Life and writing new words, paragraphs, chapters, and even books as synthetic genomics gains steam. Quite astonishingly, the beautiful design and special properties of DNA makes it capable of many other amazing feats. Here are five man-made functions of DNA, all of which are contributing to the growing “industrial-DNA” phenomenon.

The post DNA: The amazing molecule appeared first on OUPblog.

Brooke Borel’s Infested: How the Bed Bug Infiltrated Our Bedrooms and Took Over the World, a history, is the kind of book that can make you squirm—and not in a way that reassures you about the general asepsis of your mattress, hostel accommodations, luggage, vintage sweater, sexual partner, electrical heating system, duvet cover, trousseau, or recycling bin.

Consider this excerpt from the book, recently posted at Gizmodo, about the plucky bed bug’s resistance to DDT (read more at the link to learn about how it—yes, the insect—was almost drafted in the Vietnam War):

Four years after the Americans and the Brits added DDT to their wartime supply lists, scientists found bed bugs resistant to the insecticide in Pearl Harbor barracks. More resistant bed bugs soon showed up in Japan, Korea, Iran, Israel, French Guiana, and Columbus, Ohio. In 1958 James Busvine of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine showed DDT resistance in bed bugs as well as cross- resistance to several similar pesticides, including a tenfold increase in resistance to a common organic one called pyrethrin. In 1964 scientists tested bed bugs that had proven resistant five years prior but had not been exposed to any insecticides since. The bugs still defied the DDT.

Soon there was a long list of other insect and arachnid with an increasing immunity to DDT: lice, mosquitoes, house flies, fruit flies, cockroaches, ticks, and the tropical bed bug. In 1969 one entomology professor would write of the trend: “The events of the past 25 years have taught us that virtually any chemical control method we have devised for insects is eventually destined to become obsolete, and that insect control can never be static but must be in a dynamic state of constant evolution.” In other words, in the race between chemical and insect, the insects always pull ahead.

If that doesn’t, er, scratch your itch, check out the video above (produced by the Frank Collective, a rad tribe of Brooklyn-based digital media collaborators), which features Borel teasing “7 Crazy Bed Bug Facts,” and explore the book’s website, a safe space where the “bed bug queen” makes her nest.

To read more about Infested, click here.

An excerpt from Elephant Don: The Politics of a Pachyderm Posse

by Caitlin O’Connell

“Kissing the Ring”

Sitting in our research tower at the water hole, I sipped my tea and enjoyed the late morning view. A couple of lappet-faced vultures climbed a nearby thermal in the white sky. A small dust devil of sand, dry brush, and elephant dung whirled around the pan, scattering a flock of guinea fowl in its path. It appeared to be just another day for all the denizens of Mushara water hole—except the elephants. For them, a storm of epic proportions was brewing.

It was the beginning of the 2005 season at my field site in Etosha National Park, Namibia—just after the rainy period, when more elephants would be coming to Mushara in search of water—and I was focused on sorting out the dynamics of the resident male elephant society. I was determined to see if male elephants operated under different rules here than in other environments and how this male society compared to other male societies in general. Among the many questions I wanted to answer was how ranking was determined and maintained and for how long the dominant bull could hold his position at the top of the hierarchy.

While observing eight members of the local boys’ club arrive for a drink, I immediately noticed that something was amiss—these bulls weren’t quite up to their usual friendly antics. There was an undeniable edge to the mood of the group.

The two youngest bulls, Osh and Vincent Van Gogh, kept shifting their weight back and forth from shoulder to shoulder, seemingly looking for reassurance from their mid- and high-ranking elders. Occasionally, one or the other held its trunk tentatively outward—as if to gain comfort from a ritualized trunk-to-mouth greeting.

The elders completely ignored these gestures, offering none of the usual reassurances such as a trunk-to-mouth in return or an ear over a youngster’s head or rear. Instead, everyone kept an eye on Greg, the most dominant member of the group. And for whatever reason, Greg was in a foul temper. He moved as if ants were crawling under his skin.

Like many other animals, elephants form a strict hierarchy to reduce conflict over scarce resources, such as water, food, and mates. In this desert environment, it made sense that these bulls would form a pecking order to reduce the amount of conflict surrounding access to water, particularly the cleanest water.

At Mushara water hole, the best water comes up from the outflow of an artesian well, which is funneled into a cement trough at a particular point. As clean water is more palatable to the elephant and as access to the best drinking spot is driven by dominance, scoring of rank in most cases is made fairly simple—based on the number of times one bull wins a contest with another by usurping his position at the water hole, by forcing him to move to a less desirable position in terms of water quality, or by changing trajectory away from better-quality water through physical contact or visual cues.

Cynthia Moss and her colleagues had figured out a great deal about dominance in matriarchal family groups by. Their long-term studies in Amboseli National Park showed that the top position in the family was passed on to the next oldest and wisest female, rather than to the offspring of the most dominant individual. Females formed extended social networks, with the strongest bonds being found within the family group. Then the network branched out into bond groups, and beyond that into associated groups called clans. Branches of these networks were fluid in nature, with some group members coming together and others spreading out to join more distantly related groups in what had been termed a fission-fusion society.

Not as much research had been done on the social lives males, outside the work by Joyce Poole and her colleagues in the context of musth and one-on-one contests. I wanted to understand how male relationships were structured after leaving their maternal family groups as teens, when much of their adult lives was spent away from their female family. In my previous field seasons at Mushara, I’d noticed that male elephants formed much larger and more consistent groups than had been reported elsewhere and that, in dry years, lone bulls were not as common here than were recorded in other research sites.

Bulls of all ages were remarkably affiliative—or friendly—within associated groups at Mushara. This was particularly true of adolescent bulls, which were always touching each other and often maintained body contact for long periods. And it was common to see a gathering of elephant bulls arrive together in one long dusty line of gray boulders that rose from the tree line and slowly morphed into elephants. Most often, they’d leave in a similar manner—just as the family groups of females did.

The dominant bull, Greg, most often at the head of the line, is distinguishable by the two square-shaped notches out of the lower portion of his left ear. But there is something deeper that differentiates him, something that exhibits his character and makes him visible from a long way off. This guy has the confidence of royalty—the way he holds his head, his casual swagger: he is made of kingly stuff. And it is clear that the others acknowledge his royal rank as his position is reinforced every time he struts up to the water hole to drink.

Without fail, when Greg approaches, the other bulls slowly back away, allowing him access to the best, purest water at the head of the trough—the score having been settled at some earlier period, as this deference is triggered without challenge or contest almost every time. The head of the trough is equivalent to the end of the table and is clearly reserved for the top-ranking elephant—the one I can’t help but refer to as the don since his subordinates line up to place their trunks in his mouth as if kissing a Mafioso don’s ring.

As I watched Greg settle in to drink, each bull approached in turn with trunk outstretched, quivering in trepidation, dipping the tip into Greg’s mouth. It was clearly an act of great intent, a symbolic gesture of respect for the highest-ranking male. After performing the ritual, the lesser bulls seemed to relax their shoulder as they shifted to a lower-ranking position within the elephantine equivalent of a social club. Each bull paid their respects and then retreated. It was an event that never failed to impress me—one of those reminders in life that maybe humans are not as special in our social complexity as we sometimes like to think—or at least that other animals may be equally complex. This male culture was steeped in ritual.

Greg takes on Kevin. Both bulls face each other squarely, with ears held out. Greg’s ear cutout pattern in the left ear make him very recognizable

But today, no amount of ritual would placate the don. Greg was clearly agitated. He was shifting his weight from one front foot to the other in jerky movements and spinning his head around to watch his back, as if someone had tapped him on the shoulder in a bar, trying to pick a fight.

The midranking bulls were in a state of upheaval in the presence of their pissed-off don. Each seemed to be demonstrating good relations with key higher-ranking individuals through body contact. Osh leaned against Torn Trunk on his one side, and Dave leaned in from the other, placing his trunk in Torn Trunk’s mouth. The most sought-after connection was with Greg himself, of course, who normally allowed lower-ranking individuals like Tim to drink at the dominant position with him.

Greg, however, was in no mood for the brotherly “back slapping” that ordinarily took place. Tim, as a result, didn’t display the confidence that he generally had in Greg’s presence. He stood cowering at the lowest-ranking position at the trough, sucking his trunk, as if uncertain of how to negotiate his place in the hierarchy without the protection of the don.

Finally, the explanation for all of the chaos strode in on four legs. It was Kevin, the third-ranking bull. His wide-splayed tusks, perfect ears, and bald tail made him easy to identify. And he exhibited the telltale sign of musth, as urine was dribbling from his penis sheath. With shoulders high and head up, he was ready to take Greg on.

A bull entering the hormonal state of musth was supposed to experience a kind of “Popeye effect” that trumped established dominance patterns—even the alpha male wouldn’t risk challenging a bull elephant with the testosterone equivalent of a can of spinach on board. In fact, there are reports of musth bulls having on the order of twenty times the normal amount of testosterone circulating in their blood. That’s a lot of spinach.

Musth manifests itself in a suite of exaggerated aggressive displays, including curling the trunk across the brow with ears waving—presumably to facilitate the wafting of a musthy secretion from glands in the temporal region—all the while dribbling urine. The message is the elephant equivalent of “don’t even think about messing with me ’cause I’m so crazy-mad that I’ll tear your frickin’ head off”—a kind of Dennis Hopper approach to negotiating space.

Musth—a Hindi word derived from the Persian and Urdu word “mast,” meaning intoxicated—was first noted in the Asian elephant. In Sufi philosophy, a mast (pronounced “must”) was someone so overcome with love for God that in their ecstasy they appeared to be disoriented. The testosterone-heightened state of musth is similar to the phenomenon of rutting in antelopes, in which all adult males compete for access to females under the influence of a similar surge of testosterone that lasts throughout a discrete season. During the rutting season, roaring red deer and bugling elk, for example, aggressively fight off other males in rut and do their best to corral and defend their harems in order to mate with as many does as possible.

The curious thing about elephants, however, is that only a few bulls go into musth at any one time throughout the year. This means that there is no discrete season when all bulls are simultaneously vying for mates. The prevailing theory is that this staggering of bulls entering musth allows lower-ranking males to gain a temporary competitive advantage over others of higher rank by becoming so acutely agitated that dominant bulls wouldn’t want to contend with such a challenge, even in the presence of an estrus female who is ready to mate. This serves to spread the wealth in terms of gene pool variation, in that the dominant bull won’t then be the only father in the region.

Given what was known about musth, I fully expected Greg to get the daylights beaten out of him. Everything I had read suggested that when a top-ranking bull went up against a rival that was in musth, the rival would win.

What makes the stakes especially high for elephant bulls is the fact that estrus is so infrequent among elephant cows. Since gestation lasts twenty-two months, and calves are only weaned after two years, estrus cycles are spaced at least four and as many as six years apart. Because of this unusually long interval, relatively few female elephants are ovulating in any one season. The competition for access to cows is stiffer than in most other mammalian societies, where almost all mature females would be available to mate in any one year. To complicate matters, sexually mature bulls don’t live within matriarchal family groups and elephants range widely in search of water and forage, sofinding an estrus female is that much more of a challenge for a bull.

Long-term studies in Amboseli indicated that the more dominant bulls still had an advantage, in that they tended to come into musth when more females were likely to be in estrus. Moreover, these bulls were able to maintain their musth period for a longer time than the younger, less dominant bulls. Although estrus was not supposed to be synchronous in females, more females tended to come into estrus at the end of the wet season, with babies appearing toward the middle of the wet season, twenty-two months later. So being in musth in this prime period was clearly an advantage.

Even if Greg enjoyed the luxury of being in musth during the peak of estrus females, this was not his season. According to the prevailing theory, and in this situation, Greg would back down to Kevin.

As Kevin sauntered up to the water hole, the rest of the bulls backed away like a crowd avoiding a street fight. Except for Greg. Not only did Greg not back down, he marched clear around the pan with his head held to its fullest height, back arched, heading straight for Kevin. Even more surprising, when Kevin saw Greg approach him with this aggressive posture, he immediately started to back up.

Backing up is rarely a graceful procedure for any animal, and I had certainly never seen an elephant back up so sure-footedly. But there was Kevin, keeping his same even and wide gait, only in the reverse direction—like a four-legged Michael Jackson doing the moon walk. He walked backward with such purpose and poise that I couldn’t help but feel that I was watching a videotape playing in reverse—that Nordic-track style gait, fluidly moving in the opposite direction, first the legs on the one side, then on the other, always hind foot first.

Greg stepped up his game a notch as Kevin readied himself in his now fifty-yard retreat, squaring off to face his assailant head on. Greg puffed up like a bruiser and picked up his pace, kicking dust in all directions. Just before reaching Kevin, Greg lifted his head even higher and made a full frontal attack, lunging at the offending beast, thrusting his head forward, ready to come to blows.

In another instant, two mighty heads collided in a dusty clash. Tusks met in an explosive crack, with trunks tucked under bellies to stay clear of the collisions. Greg’s ears were pinched in the horizontal position—an extremely aggressive posture. And using the full weight of his body, he raised his head again and slammed at Kevin with his broken tusks. Dust flew as the musth bull now went in full backward retreat.

Amazingly, this third-ranking bull, doped up with the elephant equivalent of PCP, was getting his hide kicked. That wasn’t supposed to happen.

At first, it looked as if it would be over without much of a fight. Then, Kevin made his move and went from retreat to confrontation and approached Greg, holding his head high. With heads now aligned and only inches apart, the two bulls locked eyes and squared up again, muscles tense. It was like watching two cowboys face off in a western.

There were a lot of false starts, mock charges from inches away, and all manner of insults cast through stiff trunks and arched backs. For a while, these two seemed equally matched, and the fight turned into a stalemate.

But after holding his own for half an hour, Kevin’s strength, or confidence, visibly waned—a change that did not go unnoticed by Greg, who took full advantage of the situation. Aggressively dragging his trunk on the ground as he stomped forward, Greg continued to threaten Kevin with body language until finally the lesser bull was able to put a man-made structure between them, a cement bunker that we used for ground-level observations. Now, the two cowboys seemed more like sumo wrestlers, feet stamping in a sideways dance, thrusting their jaws out at each other in threat.

The two bulls faced each other over the cement bunker and postured back and forth, Greg tossing his trunk across the three-meter divide in frustration, until he was at last able to break the standoff, getting Kevin out in the open again. Without the obstacle between them, Kevin couldn’t turn sideways to retreat, as that would have left his body vulnerable to Greg’s formidable tusks. He eventually walked backward until he was driven out of the clearing, defeated.

In less than an hour, Greg, the dominant bull displaced a high-ranking bull in musth. Kevin’s hormonal state not only failed to intimidate Greg but in fact just the opposite occurred: Kevin’s state appeared to fuel Greg into a fit of violence. Greg would not tolerate a usurpation of his power.

Did Greg have a superpower that somehow trumped musth? Or could he only achieve this feat as the most dominant individual within his bonded band of brothers? Perhaps paying respects to the don was a little more expensive than a kiss of the ring.

***

To read more about Elephant Don, click here.

By:

Sue Morris @ KidLitReviews,

on 4/3/2015

Blog:

Kid Lit Reviews

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Picture Book,

NonFiction,

Middle Grade,

biology,

Millbrook Press,

Books for Boys,

zoology,

naturalist,

Lerner Publishing Group,

Rebecca L. Johnson,

5stars,

Library Donated Books,

quirky animal defense mechanisms,

When Lunch Fights Back: Wickedly Clever Animal Defenses,

Add a tag

x

x

x

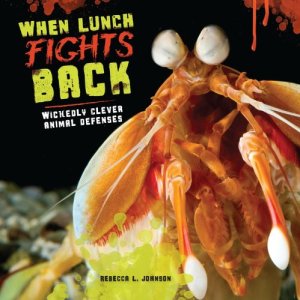

When Lunch Fights Back: Wickedly Clever Animal Defenses

Written by Rebecca L. Johnson

Millbrook Press 9/1/2015

978-1-4677-2109-7

Nonfiction Picture Book

48 pages Age 9 to 14

A Junior Library Guild Selection

“In nature, good defenses can mean the difference between surviving a predator’s attack and becoming its lunch. Some animals rely on sharp teeth and claws or camouflage. But that’s only the beginning. Meet creatures with some of the strangest defenses known to science. How strange? Hagfish that can instantaneously produce oodles of gooey, slippery slime; frogs that poke their own toe bones through their skin to create claws; young birds that shoot streams of stinking poop; and more.” [book jacket]

Review

“On Earth the challenge of survival is a real and serious business. In the wild, every living thing is constantly at risk of being eaten by something else.”

Life is a bed of strange abilities as explored in When Lunch Fights Back. These animals—and one plant—have incredible defense mechanisms. You will wonder what other odd defense mechanisms other animals might possess. I do. It also made me wonder why humans have limited natural defense abilities. Hitting, screaming, and kicking are all fine defenses, but wouldn’t it be fantastic to have some of these abilities.

1. Cover your predator with thick, slimy, goo. (Atlantic Hagfish)

2. Extend your fingers so the bones protrude through the skin like sharp claws. (African Hairy Frog)

3. Bulge out your eyes and shoot a deadly stream of blood into a predator’s mouth. (Texas Horned Lizard)

Stuff of science fiction? Nope. When Lunch Fights Back contains animals with these abilities and much more. This nonfiction picture book for older kids is a fascinating read. There is enough “yuck” to entertain kids and the author supplies the science behind those incredible abilities, making this a great adjunct text for science teachers. Author notes, a glossary, index, bibliography, and extra resources are included.

Johnson writes in a manner that should be accessible to most middle grade aged kids. She introduces researchers and scientist in the “Science Behind the Story” sections. There is so much to learn and see it just might develop a child’s interest in the natural word. If the title does not peak a child’s interest, the images will. The color photographs highlight the noxious defenses and info-boxes give additional information about each animal (scientific name, location, habitat, and size).

Still, would it not be terrific if humans could spew putrid contents at a predator, much like a fulmar? Or, and this is a tad gross, turn our other check and “shoot streams of foul-smelling feces” at an attacker, much like a hoopoe chick can do? If you had the ability to slime an attacker, like the hagfish (aka “snot eel”), I doubt anyone would mess with you.

When Lunch Fights Back: Wickedly Clever Animal Defenses is an amazing look into some crazy species. Kids will love this book and teachers can use that interest to bring out the zoologist, biologist, or naturalist in her (or his) students. While a tad gross, and most definitely with a yuck value of 9, kids will enjoy When Lunch Fights Back: Wickedly Clever Animal Defenses. This kid did!

x

WHEN LUNCH FIGHTS BACK: WICKEDLY CLEVER ANIMA DEFENSES. Text copyright © 2015 by Rebecca L. Johnson. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Millbrook Press, an imprint of the Lerner Publishing Group, Minneapolis, MN.

x

Purchase When Lunch Fights Back at Amazon —B&N—Book Depository—Lerner Books.

—B&N—Book Depository—Lerner Books.

x

Learn more about When Lunch Fights Back HERE.

Meet the author, Rebecca L Johnson, at her website: http://www.rebeccajohnsonbooks.com/

Find more MG Nonfiction at the Lerner Publishing Group website: https://www.lernerbooks.com/

Millbrook Press is an imprint of Lerner Publishing Group.

Copyright © 2015 by Sue Morris/Kid Lit Reviews

Filed under:

5stars,

Books for Boys,

Library Donated Books,

Middle Grade,

NonFiction,

Picture Book Tagged:

biology,

Lerner Publishing Group,

Millbrook Press,

naturalist,

quirky animal defense mechanisms,

Rebecca L. Johnson,

When Lunch Fights Back: Wickedly Clever Animal Defenses,

zoology

By: DanP,

on 3/9/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

health,

science,

genetics,

Medical Mondays,

biology,

birth,

babies,

pregnancy,

fertility,

alternative medicine,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

fertility and pregnancy,

genomes,

in vitro fertilization,

ivf,

Science & Medicine,

Earth & Life Sciences,

a child of one's own,

designer babies,

rachel bowlby,

three parent babies,

Add a tag

The news that Britain is set to become the first country to authorize IVF using genetic material from three people—the so-called ‘three-parent baby’—has given rise to (very predictable) divisions of opinion. On the one hand are those who celebrate a national ‘first’, just as happened when Louise Brown, the first ever ‘test-tube baby’, was born in Oldham in 1978. Just as with IVF more broadly, the possibility for people who otherwise couldn’t to be come parents of healthy children is something to be welcomed.

The post The third parent appeared first on OUPblog.

An excerpt from Seeing Green: The Use and Abuse of American Environmental Images

by Finis Dunaway

***

“The Crying Indian”

It may be the most famous tear in American history. Iron Eyes Cody, an actor in native garb, paddles a birch bark canoe on water that seems at first tranquil and pristine but becomes increasingly polluted along his journey. He pulls his boat from the water and walks toward a bustling freeway. As the lone Indian ponders the polluted landscape and stares at vehicles streaming by, a passenger hurls a paper bag out a car window. The bag bursts on the ground, scattering fast-food wrappers all over his beaded moccasins. In a stern voice, the narrator comments: “Some people have a deep abiding respect for the natural beauty that was once this country. And some people don’t.” The camera zooms in closely on Iron Eyes Cody’s face to reveal a single tear falling, ever so slowly, down his cheek (fig. 5.1).

This tear made its television debut in 1971 at the close of a public service advertisement for the antilitter organization Keep America Beautiful. Appearing in languid motion on television, the tear would also circulate in other visual forms, stilled on billboards and print media advertisements to become a frame stopped in time, forever fixing the image of Iron Eyes Cody as the Crying Indian. Garnering many advertising accolades, including two Clio Awards, and still ranked as one of the best commercials of all time, the Crying Indian spot enjoyed tremendous airtime during the 1970s, allowing it to gain, in advertising lingo, billions of “household impressions” and achieve one of the highest viewer recognition rates in television history. After being remade multiple times to support Keep America Beautiful, and after becoming indelibly etched into American public culture, the commercial has more recently been spoofed by various television shows, including The Simpsons (always a reliable index of popular culture resonance),King of the Hill, and Penn & Teller: Bullshit. These parodies—together with the widely publicized reports that Iron Eyes Cody was actually born Espera De Corti, an Italian-American who literally played Indian in both his life and onscreen—may make it difficult to view the commercial with the same degree of moral seriousness it sought to convey to spectators at the time. Yet to appreciate the commercial’s significance, to situate Cody’s tear within its historical moment, we need to consider why so many viewers believed that the spot represented an image of pure feeling captured by the camera. As the television scholar Robert Thompson explains: “The tear was such an iconic moment. . . . Once you saw it, it was unforgettable. It was like nothing else on television. As such, it stood out in all the clutter we saw in the early 70s.”

FIGURE 5.1. The Crying Indian. Advertising Council / Keep America Beautiful advertisement, 1971. Courtesy of Ad Council Archives, University of Illinois, record series 13/2/203.

As a moment of intense emotional expression, Iron Eyes Cody’s tear compressed and concatenated an array of historical myths, cultural narratives, and political debates about native peoples and progress, technology and modernity, the environment and the question of responsibility. It reached back into the past to critique the present; it celebrated the ecological virtue of the Indian and condemned visual signs of pollution, especially the heedless practices of the litterbug. It turned his crying into a moment of visual eloquence, one that drew upon countercultural currents but also deflected the radical ideas of environmental, indigenous, and other protest groups.

At one level, this visual eloquence came from the tear itself, which tapped into a legacy of romanticism rekindled by the counterculture. As the writer Tom Lutz explains in his history of crying, the Romantics enshrined the body as “the seal of truth,” the authentic bearer of sincere emotion. “To say that tears have a meaning greater than any words is to suggest that truth somehow resides in the body,” he argues. “For [Romantic authors], crying is superior to words as a form of communication because our bodies, uncorrupted by culture or society, are naturally truthful, and tears are the most essential form of speech for this idealized body.”

Rather than being an example of uncontrolled weeping, the single tear shed by Iron Eyes Cody also contributed to its visual power, a moment readily aestheticized and easily reproduced, a drop poised forever on his cheek, seemingly suspended in perpetuity. Cody himself grasped how emotions and aesthetics became intertwined in the commercial. “The final result was better than anybody expected,” he noted in his autobiography. “In fact, some people who had been working on the project were moved to tears just reviewing the edited version. It was apparent we had something of a 60-second work of art on our hands.” The aestheticizing of his tear yielded emotional eloquence; the tear seemed to express sincerity, an authentic record of feeling and experience. Art and reality merged to offer an emotional critique of the environmental crisis.