new posts in all blogs

Viewing Blog: , Most Recent at Top

Results 1 - 25 of 86

Statistics for

Number of Readers that added this blog to their MyJacketFlap:

By: Stephanie Campisi,

on 11/17/2013

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

The Most Underrated Book Award 2013, which I helped judge, was announced on Friday at the close of the SPN Independent Publishing Conference. The winner was the wonderful Fish-Hair Woman by Merlinda Bobis (Spinifex Press).

In case it’s of interest, here’s a transcript of the speech I gave on the night.

The day after I was asked to help judge the Most Underrated Book Award, an enormous box of books was delivered to my office.

This experience was surprising for two reasons. First, my dealings with Australia Post haven’t usually involved timely delivery. Second, the box was filled to the brim with erotic romance.

Had I misunderstood the brief entirely?

Was this “underrated books” business something to do with the Ratings Classification Board? Had Tony Abbott, always industrious about such things, enacted some sort of public decency act?

I was quite relieved when a second box, its contents entirely safe for work, arrived a few days later.

But again, as I sifted through my box of award candidates, I was struck with uncertainty.

Thanks to my unwitting exposure to such classy titles as Wallbanger, I now had a fairly good idea of what made a book X-rated, but what about underrated?

Could such a thing be judged? Had the Small Press Network overrated my skills at rating the underrated? And, what’s more, wasn’t the very title of the award a paradox?

My fellow judges had similar questions, and we spent some time trying to come up with a workable definition.

What was meant by underrated in the literary world?

Did underrated mean a book that had been well reviewed but that hadn’t sold as well as intended?

Was it one that had sold well but that hadn’t received the hoped-for media coverage or critical acclaim?

In my experience, books hold the answers to most problems, so I set aside these concerns for a while and started to read.

And as I worked my way through the nominees—some of them strange and lovely, others bold and raw, others a bizarre but striking explosion of narrative verve—I realised that I’d been thinking about the word “underrated” entirely incorrectly.

Somehow in my head, perhaps from watching all those episodes of Daria as a pre-teen, “underrated” had become synonymous with “underachieving”.

And that wasn’t at all the case. Underachieving implies deficiency.

Underrated, on the other hand, implies that something special has gone somewhat unrecognised for whatever reason.

And as I read for this award, marvelling at the sheer gutsiness of some of these authors and the publishers who had backed them, I realised just how true that was.

An underrated book has all of the hallmarks of a good quality, successful, enduring title.

It simply moves on a different trajectory. Its journey is different from other books.

An underrated book is a quiet achiever. One that trickles its way into the collective consciousness.

One that affects you in such a way that you only want to recommend it to those you trust enough to properly appreciate it. It’s the one you’ve probably passed along to a friend with a disclaimer about the ugly cover or the tiny print or the fact that half of the pages are falling out.

It’s the kind of book that ends up full of marginalia and covered in coffee-stains because it’s always within reach for anyone desperate for a makeshift coaster. You’ve probably invested in two copies for this reason.

It’s the kind of book that can never be overrated, because it’s hand-sold only by people who are truly touched by it, rather than indifferently passed along because you want to free up some space on your shelves.

An underrated book never explodes upon the market so quickly that it gets picked up by an audience that is wrong for it, or by critics grudgingly assigned to the key titles of the season. It’s never pitched as Bestselling Movie X meets Bestselling Movie Y…with zombies.

An underrated book is one that requires a little bit more patience than today’s fickle, fleeting marketplace allows, which is why we’re lucky to have this award.

I’ve heard the award—on that highly regarded peer-reviewed medium that is Twitter—described as a backhanded compliment. But I promise you that “most underrated” and “least overrated” aren’t synonymous, just as “underrated” and “underachieving” aren’t.

Nor is the MUBA some sort of parochial bookish movement to celebrate the literary underdog or the battler.

The books on the shortlist are books that I—and the other judges—honestly feel are going to resonate.

But resonance by definition is something that isn’t instantaneous or short-lived.

It lingers. It affects you. And maybe it changes you just a little bit.

The MUBA is designed to help these books sustain that note.

An underrated book is an underground book.

It’s also a lucky book.

Because today’s underground book is tomorrow’s cult classic.

And being dubbed a cult classic is not only tremendously cool, but it also means that your book will neatly sidestep the indignity of being involved in a zombie mash-up.

You can find more about the shortlisted titles on the SPN website, and purchase them from Readings or other local booksellers.

The post Why today’s underrated books are tomorrow’s cult classics appeared first on Read in a Single Sitting - short books, page-turners, and books you can't put down.

By: Stephanie Campisi,

on 11/5/2013

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

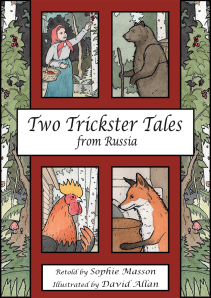

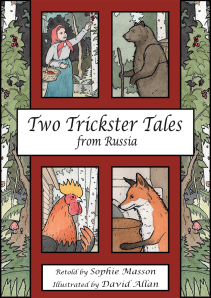

“There’s not a lot of traditional material for kids being produced in Australia,” says Sophie Masson, one of the co-founders of Christmas Press, a new boutique picture book publisher with a focus on folktales and traditional stories.

Many mainstream publishers are looking to “quirky” and nontraditional titles as a point of market differentiation, she notes, but this approach has its own problems: quirkiness becomes necessarily less so when moulded for mainstream appeal.

In contrast, Two Trickster Tales from Russia, the debut title from Christmas Press, stands out from the crowd by virtue of its traditional content and design.

“Fairy tales and folktales endure for a reason. They contain deep emotional truths that keep resonating down the centuries,” she says. “And they’re a lot of fun!”

Illustrator David Allan adds that the editorial team’s decision to focus on fairy tales arises from a simple, but pure motivation: a shared love of folk tales, mythology and traditional storytelling.

“We wanted to produce the type of books that we would want to be enchanted by. The book market can be like fashion in some ways, chasing the flavour of the month or year.”

Illustrator and designer Fiona McDonald recalls browsing with Sophie through the Christmas-themed children’s titles one year and being disappointed by the selection on offer.

“We were rather sad to see that in the very slim selection there were a large number of versions of the Twelve Days of Christmas. We playfully suggested we start our own press and call it Christmas Press.”

A question of reading

A recent article in the Guardian described an apparent trend away from bedtime reading in favour of digital forms of entertainment, and given the trio’s emphasis on traditional stories, I’m curious to get their thoughts on this.

None of them, it turns out, is overly worried.

“Human beings have been story-creatures from the beginning of time, and experiments with storytelling have existed since the beginning of time, too,” says Sophie.

“I go into lots of schools and libraries to talk to kids about books and reading and don’t think there are any less children reading than before—the big readers always were in a minority, and there were always some who never read at all, but in general kids read more than adults, these days as much as before.”

Fiona and David both feel strongly that there is still room in the market—and in our lives—for good quality children’s books.

Fiona, who runs a toyshop specialising in hand-made and old-fashioned toys, has seen first-hand that the lure of digital media doesn’t have to be at the expense of traditional reading approaches.

“Personally, I feel there will be a major return to books and reading for pleasure and some of the old fashioned ways of doing things.”

David adds that he believes that traditional books and digital media can happily coexist.

“We started Christmas Press to produce picture books that we would love and weren’t really considering it from a position of being concerned about the worries of people going digital.”

Folk tales from Russia and beyond

The decision to lead with Sophie’s Russian folk tale retellings was an easy one given that all three felt strongly about the title. Not to mention that David had already prepared some sample illustrations for it as part of a submissions package.

“My style has been heavily influenced by traditional illustrators from the turn of the last century, like Arthur Rackham, along with the flourish of Art Nouveau, so I’m in my element with Two Trickster Tales,” he says.

And thanks to Sophie’s abiding love of Russian art and illustration, David found himself introduced to the work of the great Russian illustrator Ivan Bilibin, whose style had a strong influence on the artwork found in the book.

This is precisely the type of outcome that Christmas Press hopes to achieve with its stylish, culturally rich titles.

“It certainly does say something that mainstream publishing is not seeing the potential in these diverse cultural influences,” says Sophie.

“The response we’ve had already from readers—both young and older—as well as booksellers, libraries and schools, does suggest a failure to see potential!”

One of the benefits of being a small press working with small print runs is the ability to carefully target a niche, something that Sophie notes that a larger house dealing with larger print runs may find not economical.

Fiona adds that we’ll see more folktales forthcoming from Christmas Press: May 2014 will see the publication of Two Selkie Stories from Scotland, retold by Kate Forsyth and illustrated by Fiona McDonald, with Two Tales of Twins from Ancient Greece and Rome retold by Ursula Dubosarsky and illustrated by David Allan to follow.

The economics of crowd-funding

Two Trickster Tales was partly funded through an IndieGoGo campaign, which Sophie describes as a far more appealing alternative to applying for a government grant.

“Government grants are a pain to apply for, very difficult to get, and I’m not sure our enterprise would fit comfortably into any of their categories,” she says when asked about this decision.

Fiona adds that the timelines involved in the grant application process can also be a source of frustration.

And where the grant application process engages a bureaucracy, crowd-funding goes direct to the consumer.

“To people who love books and want to support creativity and enterprise,” says Sophie.

She adds the caveat that although crowd-funding can help with both publicity and preliminary market testing, it’s not a true test of the viability of a product–many of the project’s supporters were fellow authors and creatives.

“A much more practical test happens later,” she says, “when you start going around the bookshops and libraries and people are snapping up copies to sell in their shops because they think the book is so beautiful.”

“Seeing our first book in print,” says Fiona, who was behind the internal layout, “was so exciting that it is making me impatient to start the next. I can’t wait for the next volume to come out so I can add it to my collection of beautiful picture books.”

Two Trickster Tales can be purchased from the Christmas Press website

The post Christmas Press heralds a return to traditional picture book publishing in Australia appeared first on Read in a Single Sitting - short books, page-turners, and books you can't put down.

By: Stephanie Campisi,

on 7/31/2013

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

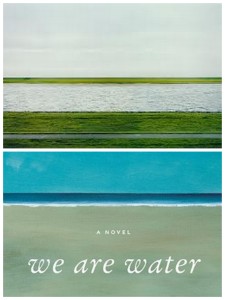

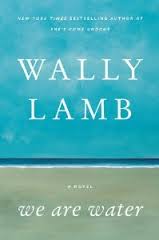

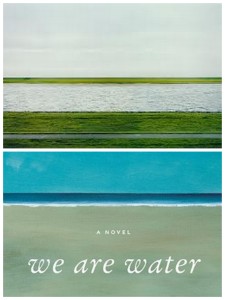

When browsing through my many bookish newsletters today I came across an ad for Wally Lamb’s latest release We Are Water, and was struck by the cover design, which I found fiercely reminiscent of Rhein II, the photograph by Andreas Gursky that famously sold for a record $4.3m in 2011. I’m not sure whether the composition is a deliberate reference or a case of great minds (although I might try to get in touch with the designer to find out), but I’m now curious about other book covers that might have been inspired by famous works of art or design. Do any others come to mind?

The post Cover designs inspired by art: Wally Lamb’s We Are Water and Rhein II by Andreas Gursky appeared first on Read in a Single Sitting - short books, page-turners, and books you can't put down.

By: Stephanie Campisi,

on 7/16/2013

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

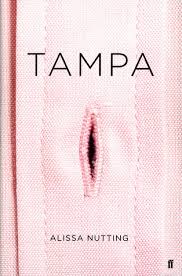

If I were to peg a book as 2013′s most controversial release, Alissa Nutting’s Tampa, would probably be it. I’ll be reviewing the book shortly, but in the meantime the generous people at Allen & Unwin have offered copies of the book to give away to five of my Australian readers.

To enter, simply fill in the Rafflecopter form below. That said, I’d love to hear your thoughts on the book–pitched as a contemporary Lolita from a female perspective–and on its highly suggestive Australian cover.

About the book:

Celeste Price is an eighth-grade English teacher in suburban Tampa. She is attractive. She drives a red Corvette. Her husband, Ford, is rich, square-jawed and devoted to her. But Celeste has a secret. She has a singular sexual obsession – fourteen-year-old boys. It is a craving she pursues with sociopathic meticulousness and forethought. Within weeks of her first term at a new school, Celeste has lured the charmingly modest Jack Patrick into her web – car rides after dark, rendezvous at Jack’s house while his single father works the late shift, and body-slamming encounters in Celeste’s empty classroom between periods. It is bliss.

Celeste must constantly confront the forces threatening their affair – the perpetual risk of exposure, Jack’s father’s own attraction to her, and the ticking clock as Jack leaves innocent boyhood behind. But the insatiable Celeste is remorseless. She deceives everyone, is close to no one and cares little for anything but her pleasure.

With crackling, stampeding, rampantly sexualised prose, Tampa is a grand, satirical, serio-comic examination of desire and a scorching literary debut.

a Rafflecopter giveaway

The post Giveaway: Tampa by Alissa Nutting appeared first on Read in a Single Sitting - short books, page-turners, and books you can't put down.

By: Stephanie Campisi,

on 7/16/2013

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

Some months ago, during my efforts to seek climate-controlled asylum from Melbourne’s oppressive summer days, I found myself in an independent bookshop known for its having both superior air conditioning and superior floor stock.

Not to mention a superiority complex.

Aware that my literary credibility was being assessed by the twin forces of the fauxhawked staff and the hipster/professorial customers, each toting a book written by an author whose name featured more diacritics than letters, I went straight for the (translated) classics section and dug about for something suitably obscure.

Which was not so hard, really, as this particular shop does not stock mass-market paperbacks. Its mainstream section is notable for just about every item’s being imbued with a Pulitzer or a Booker or a Nobel. The occasional bestseller glimpsed here and there is a thorn of bibliophilic affront, something endured only by being approached with a palpable sense of irony. (And a shelf-talker underscoring the point.)

It certainly is not the sort of shop that one would go to in search of a certain widely popular yet widely derided book whose title is redolent of a Dulux paint palette.

Needless to say, I looked on in interest over my copy of Summer in Baden-Baden as a harried-looking customer dashed into the shop seeking said volume posthaste.

Curiously, the name of this book—obviously verboten in this altar of the written word—was never actually mentioned in his negotiations with the moustachioed bookstore guy. A guy whose very aura of literariness would make even the most well read person question their bookish credentials.

The customer left the shop with several books that were a variation on the theme that he was after—I believe that Anais Nin was, ahem, on top—and though his original sought-after prize might have been amongst them, it certainly wasn’t his only purchase.

As I went back to parsing Tsypkin’s endless sentences (need proof of the Chomskyian concept of linguistic recursion? Look no further!) I found myself thinking about the influence of intellectual scrutiny.

I’m entirely aware that I’m inviting a skewering in the comments section, but in my opinion, the value of the book snob is severely underrated.

Discussions about the role of bookshop staff often revolve, perhaps erroneously, around the knowledge of such staff, when in fact I suspect that one of their most important attributes is actually the sense of literary accountability they instil within us.

People are egocentric. We seek validation and acceptance. We’re also aspirational.

I don’t want to be judged for purchasing crappy books.

So many of my purchases over the years have been influenced by my desire not to be viewed as some sort of intellectually bankrupt cretin. And in a similar vein, much of my reading—especially my public reading—is surely affected by the idea of being subjected to the scrutiny, real or perceived, possible or actual, of others around me.

People like me have historically lived in a biblio-panopticon, mindful that at any time an intellectual gatekeeper could pop up in the central tower of our literary lives and subject us to…well, probably to a tut-tut. Perhaps a raised eyebrow at worst.

But such a thing strikes terror into my nerdy little heart.

The concept of fearing being found wanting in an intellectual or bookish capacity probably sounds ludicrous to some, but book snobs—along with those ambassadors for other types of cultural snobbery—play an essential role in shaping and developing our intellectual, cultural and philosophical engagement.

And I think that now, more than ever, the tut-tutting, eyebrow-crooking book snob is needed.

We live in an era where book purchasing has become increasingly anonymous, and where, with the rise of reading on e-readers and other devices, reading itself has become increasingly anonymised.

And with anonymity comes the retreat of accountability and all that entails—typically either a bacchanal madness or sheer laziness. (The latter, most likely.) In a literary context, the result is the disengagement with the difficult, the strange, and the challenging.

The cycle is only worsened by that bane on the imaginative worlds of humanity: the internet recommendation engine. Because as Kurt Vonnegut would concur, there’s nothing quite like using a machine to quantify the inherently human capacity for taste and imagination.

By recommending only books that are similar to what you or others have previously purchased and liked, these engines serve the opposite purpose of what a bookshop staff member should: they provide suggestions that will inevitably and necessarily narrow towards a mean of the average, the safe, the dull, and the unchallenging.

This isn’t to suggest that people should only be reading free-verse poetry translated from Hungarian and printed upside-down on T-shirts in heat-activated ink.

However, without the occasional well-coiffed invigilator to sniffingly guide us away from the easy choices and on to another, perhaps more dangerous, but certainly more interesting path, it’s a worrying likelihood that we’ll never even have the chance to be exposed to such things.

Certainly, the haughty gaze of the literary snob can be an uncomfortable lens through which to be assessed. But when it comes to challenging people to enrich their intellectual lives, a little snobbery can go a long way.

So, I will continue to judge you by your choice of reading matter, and I hope that you’ll hold me to the same degree of literary accountability.

Because we owe it to our cultural acuity to openly and constructively critique each other’s intellectual lives.

Here’s to being a snob.

The post An Ode to Book Snobs appeared first on Read in a Single Sitting - short books, page-turners, and books you can't put down.

By: Stephanie Campisi,

on 6/11/2013

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

A week or so ago, I read with distinct amusement the commentary of two Twitter friends who were attending the Malcolm Gladwell lecture at Book Expo America. Each was live tweeting the event, and in verbose, manic style, their tweets filling my feed to the exclusion of pretty much everything else. But what made things so fascinating was that their tweets were fundamentally, diametrically opposed–one gladly worshipped at the altar of all things Gladwell; the other decried him as a charlatan Pied Pipering his unquestioning listeners down a rabbit hole of rubbish–and yet, though they were in the same space, and even reporting using the same hashtag, they weren’t engaging with each other in the least.

I mentioned this to my husband, who suggested that the two had probably blocked each other. That though they might well be sitting side by side in the auditorium, they were so ensconced in their personal ideological silos that they had no intention of letting someone else breach those walls. But it seemed so strange, I responded, pointing out that each was a highly articulate, thoughtful individual who had something to bring to the debate, and that the very fact that they were attending the same event, regardless of their personal perspectives about what was being said, showed that they clearly had some aligned interests and concerns. If only Twitter could prepare a graph or a diagram showing who had blocked each other, said my husband. Doing so would be an excellent way of identifying both communication and information breakdowns: an ideological schism over which information, ideas and debate had no means of passing.

These sorts of divisions are nothing new, and are one of the key themes of Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South, which looks at both the physical and social divide between those of the landowning, educated classes and those of a working-class background. The novel traces the journey of Margaret Hale as she moves from the well-to-do, buffered south to the industrial town of Milton in the north, a place currently unsettled by conflict over workers’ rights and the relatively new development of the entrepreneurial middle class. Margaret’s initial ignorance regarding the Milton context is such that she is thrown into circumstances that are utterly alien to her. (Upon arriving, she despairs for her situation: “If she had known how long it would be before the brightness [either internal or external] came, her heart would have sunk low down…”) Her slow ingratiation into Milton society comes in a gradual, iterative manner, with Margaret first needing to acknowledge the existence of the place and its people, and then begin to humanise and empathise with her new peers.

“Your lives and your welfare are so constantly and intimately interwoven,” she argues at one point, highlighting the connectedness of both worker and employer, “God has made us so that we must be mutually dependent. We may ignore our own dependence, or refuse to acknowledge that others depend upon us in more respects than the payment of weekly wages; but the thing must be, nevertheless. Neither you nor any other master can help yourselves. The most proudly independent man depends on those around him for their insensible influence on his character–his life.”

And the same is true of ideas: aligning oneself only with those whose beliefs are our own is deeply problematic and can only represent an ideological narrowing.

As the book progresses, Margaret becomes quite demonstrative in her proclamations of equality and empathy, and we see her striving to play the role of cultural anthropologist, seeking to understand her new circumstances. But the inciting event behind her engagement is obvious: her coming into contact with this place, these people, these ideas in the first place. Had she and her family remained in their isolated social and ideological silo in the south, Margaret would have remained entirely ignorant of life in Milton, and would have found herself surrounded only by those whose ideas, goals, and outlooks she shared–the possible exception being her father, whose defection from the church signifies a potential opportunity for an ideological clash and therefore a resultant, accompanying growth.

“There might be toilers and moilers there in London” (where Margaret lived at one point) “but she never saw them; the very servants lived in an underground world of their own, of which she knew neither the hopes nor the fears; they only seemed to start into existence when some want or whim of their master or mistress needed them.”

And yet, while Margaret slowly begins to make her way across a variety of social, class, and linguistic borders, others around her refuse to do so. (“And if I must live in a factory town, I must speak factory language when I want it. Why, mamma, I could astonish you with a great many words you’ve never heard in your life.”) Her mother, for example, is intent upon maintaining the wall between her erstwhile life and her new one, and upon arriving in Milton immediately falls ill, becoming housebound and isolated. Her determined disconnection from all that Milton represents could be argued to be a contributing factor to her eventual demise, and one that I’d argue is as much an ideological or existential death as a physical one. Ideas are what make us human, after all, and by refusing to engage with a differing point of view or way of living, Margaret’s mother is slowly asphyxiating her intellectual self. It’s hard not to see this as Gaskell’s warning about the dangers of close-mindedness and deliberate ignorance. Without sustained intellectual debate, without being subjected to ideas and situations that frustrate us, that are abhorrent to us, that make us uncomfortable, or that make us feel anything other than warm and fuzzy, we risk severing ourselves from the wider context of reality.

“Mr Thornton is coming to drink tea with us tonight,” said Mr Hale, “and he is as proud of Milton as you of Oxford. You two must try and make each other a little more liberal-minded.”

“I don’t want to be more liberal-minded, thank you,” said Mr Bell.

Perhaps what bothers me most about the ideological schisms we see today, the conversational black-outs that occur thanks to blocking and other siloed forms of information access/restriction, is that they are far more deliberate than in the time when Gaskell was writing. Where Gaskell’s characters could be forgiven their ignorance in many instances due to their physical isolation and their relative inability to obtain information, today we’re far more deliberately choosing to ignore people whose mindsets or beliefs clash with ours. Even worse is the idea of blocking someone: if you ignore someone you are at least aware of their behaviour or their presence; by blocking that individual, you preclude that entirely. Yes, the sheer degree of connectedness of our world means that it can be immensely tiring to constantly engage with differing ideologies or beliefs, but we owe it to ourselves and to our intellectual richness not to cut ourselves off from these viewpoints, to at least try to consider the perspectives of others–and the people who hold those perspectives.

“Margaret the Churchwoman, her father the Dissenter, Higgins the Infidel, knelt down together. It did them no harm.”

Support Read in a Single Sitting by purchasing North and South using one of the affiliate links below:

Amazon | Book Depository UK | Book Depository USA | Booktopia

or support your local independent.

The post Ideological silos, blocking people on Twitter, and Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South appeared first on Read in a Single Sitting - short books, page-turners, and books you can't put down.

By: Stephanie Campisi,

on 6/1/2013

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

If you were to ask me to name one of the more unusual collocations in the English language, “exquisite corpse” would have to be one of them.

Fortunately for those of us of squeamish constitution, it refers not to some sort of questionable forensic titillation, but rather to a type of collaborative story-telling whereby participants would turn by turn compile a narrative.

The concept has remained popular over the years, but with the rise of social media has experienced a sort of virtual renaissance. Two notable recent projects include Tim Burton’s crowd-sourced Cadavre Exquis, and Neil Gaiman’s fan-sourced Twitter story.

The newest addition to the genre is the Unfinished Phrase iPhone app, to be launched today at the close of Melbourne’s Emerging Writers’ Festival.

The app is the brainchild of former EWF “Geek in Residence” Pierre Proske, who was inspired to develop a collaborative storytelling platform after attending the EWF event last year.

Although Proske studied literature as part of his combined arts/engineering degree at university, he doesn’t necessarily harbour writing aspirations himself. It came as somewhat of a surprise to him, then, that during his attendance at the EWF that he found himself quite excited by the idea of writing.

“I was actually really impressed by that given that I wasn’t strictly the target market. I attended a lot of panels and things and got really excited about writing and getting published, which was quite exciting and quite surprising.”

That said, he noticed that throughout the festival there wasn’t actually a great deal of writing actually going on. The focus was instead more about absorbing information from other writers and publishing experts.

But the idea of harnessing the creative passion and energy that was apparent at the festival remained with Proske.

“I wanted to capitalise on that energy in some way, and I thought perhaps one solution was to have a small, playful app that people could engage with without having to be dragged into that whole ‘I have to write a whole short story’ thing. Something that wasn’t too overwhelming or massive, but that was still getting people to write.”

The fact that the EWF was such a collaborative event was a key realisation: Proske wanted to make the most of the fact that in this sort of festival situation writers are surrounded by other similarly minded people.

“That was essentially the key realisation that drove me to then propose an app that could be used during the festival. The EWF was looking for digital media proposals for the next festival, and I came across the concept of an app that was more or less based on the concept of the exquisite corpse, where you write one thing after another.”

Proske’s research into the idea led him to all manner of online collaborative story-telling experiments, and he was confident that the idea had potential. The longevity of such projects remains somewhat of a question mark, however, and he was mindful of this when pitching the idea.

“I’m not sure if it can really work well over the long-term. The evidence suggests that maybe it doesn’t because these other sites have an initial amount of energy and then it drops of. Tim Burton ran his project for one or two weeks and then sort of wrapped it up, so it wasn’t a never-ending sort of thing. This is what I envisaged for the festival as well. At this point in time we’re just doing a one-night event as part of the closing part of the festival.”

In addition to timeliness, another key fact was that the barrier to entry should be kept low so that people wouldn’t be intimidated about participating.

“It was just meant to be fun and fast,” says Proske. “I developed a simple prototype using WordPress, then applied for some funding from the Australia Council.”

Finding someone to help develop the app for the iOS platform was a little more difficult, however, not just from the budgetary side of things, but also because Proske wanted to be able to work with a team who would see the app not just as a client job, but more of an “art project”.

“At one point I’d sorted of decided that I’d do it myself, because I sort of liked the idea of having control over the project over the long term—if we’d worked with a faceless company, if we didn’t have any further funding it might have made it difficult to resurrect it or make changes.”

But when Proske met Jonathan Chang of Silverpond (disclosure: my husband) at an event, he felt that he’d found someone who understood what he was trying to achieve with the app. And Proske has plenty of plans for it.

“I’m very excited for this thing to continue and maybe take a stronger shape, because there are other possibilities in terms of for example harnessing Twitter to promote people’s writing while they’re using the application.”

The app currently requires a Twitter account in order to log in, which was seen as a reasonable requirement given how active the EWF audience seemed to be on Twitter. Further possibilities exist here, too.

“In the future it would be nice to publish the story with a particular handle, or even particular fragments on Twitter, or even other social networks. For example, if you do contribute to a story, you can have the opportunity to share your little quote somewhere. This might bring in new people to the app, and they might then register and engage and so on.”

Engagement is key to the app’s success, says Proske, who is aware that a certain critical mass is needed in order to develop the momentum the app will need to create sustained interest.

“If there’s constant activity and people responding to your thread or story, then you’d become very much engaged and want to see it through to the end. We haven’t been able to do a large beta test, so the closing party will be an initiation into that, to see how well it works.”

If the app does see the kind of engagement that Proske hopes for, he’s confident that it can be used in a variety of different contexts.

“It could very well be reused for different events, or in an ongoing way. There are actually a lot of possibilities. Hopefully everyone there tonight will be encouraged to engage with the story, so at least there’ll be a whole bunch of activity going on, and also it’s the end of the festival, so maybe people won’t be so uptight in terms of writing.”

Part of his excitement stems from the fact that with this sort of storytelling platform it’s impossible to know what the result will be.

“At the moment it’s pretty raw. We’ve left it totally open. I really don’t know what to expect. The app will be public, and once it does get launched, it will get attention, and I assume we’ll probably keep it open, at least for a little while. I am kind of excited to see how it pans out, and I hope it will engage a wider public.”

The Unfinished Phrase app is available on iTunes.

Visit the Unfinished Phrase website.

This article is also available on ArtsHub.com.au

The post Interview: Pierre Proske on the Unfinished Phrase iPhone App appeared first on Read in a Single Sitting - short books, page-turners, and books you can't put down.

By: Stephanie Campisi,

on 5/27/2013

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

Late last year I attended a lecture with David Shields, author of Reality Hunger and ardent and vociferous proclaimer of the death of the novel. In Shields’ view, authors wishing to create new and relevant work work need to turn away from what he sees as the outmoded and irrelevant nineteenth century approach to the novel, and instead look at breaking through traditional narrative barriers and working with new forms.

With its media-enhanced approach to storytelling, allowing authors to build a narrative incorporating audio tracks, images, links and more, the Creatavist platform certainly allows for this. I was given the heads-up about the platform by Sydney-based author Daniel Dalton, who recently used it to publish an enhanced version of his short story Perfect.

I was intrigued by the way that the Creatavist version of Perfect incorporated newspaper articles, Wikipedia entries and a narrative track into what was originally a traditionally told story, and decided to catch up with Dan for a chat about the affordances of the platform—and what it might mean for, or indicate about, modern-day approaches to storytelling.

The first question I wanted to put to Dan was the notion of the “enhanced” story, and what exactly this very loaded term means. After all, a recent critique of the non-fiction piece “Snow Fall” seems to indicate that there’s some ambivalence about the value of multimedia story-telling platforms and whether they truly enhance the storytelling experience…or are merely the narrative equivalent of 3D.

“At the beginning it’s very much going to be about novelty, about playing around,” admits Dan. “But someone is going to come along and do something magical with it. Someone will come along with some real multimedia skills and tell a story that involves video and media in a way that’s inherent to the story, rather than as a sideline. Those bits of media will be really essential to the story. I don’t think that platforms like Creatavist are in any way replacing anything—Creatavist is just a new tool to do what we’ve already been doing. Telling stories.”

Dan’s perspective in a way echoes mine: that Creatavist, despite its techno-geek trappings, is actually harking back to an older form of story-telling where the author and narrator exist as a buffer between the reader and the narrative, something that has become increasingly rare in modern-day fiction. The inclusion of footnotes, images and so forth result in the foregrounding of storyteller—and simultaneously demonstrate an awareness of the existence of the reader.

“I’ve been re-reading The Great Gatsby, and Nick Carraway is very present as the narrator,” says Dan. “He’s telling the story, and he knows that he’s telling it to you, the reader. Something I try to do when I write first person narratives is think that, yes, this person is telling a story, but who are they telling it to, and why?”

Dan notes that in contemporary fiction much of this author-audience engagement has disappeared, with first person narration often tending towards the narrator “talking into space”, with the plot being foregrounded instead. Working with Creatavist allowed Dan to have his narrator engage directly with the audience.

“I enjoyed being able to insert those little moments where the character makes you step back [and gives you information], rather than leaving you to google something after you’ve read the story. The narrator is a personal trainer, and he’s a centre of knowledge of those things. The multimedia devices in the story give him a chance to explain what he’s talking about. It’s sort of an older style, but I think that that’s what first person narration was, and really should be. The narrator should own the story.”

In an era where director’s cuts and commentary abound, and where readers seem to want to engage with the author beyond their work, a platform like Creatavist also opens up another entirely different possibility: bringing the author to the forefront. Does Creatavist provide a way for authors to add layers of extra-narrative commentary to their work?

“I hadn’t necessarily thought about using it for that, for adding your intentions into a text,” says Dan, adding that he subscribes to the Roland Barthes theory about the death of the author.

“What I’ve created has absolutely nothing to do with me, but lives with the reader. While I’m happy to give the narrator of my story complete power, I’m less happy to give myself that complete power and prescribe my intentions for the text. It sounds a bit pretentious, but I don’t want you as a reader feel like you have to interpret it in a certain way. Obviously when I wrote Perfect I had intentions in mind, but you can read it in many different ways. As sort of quite shallow torture porn, or as a look at the male psyche, or the culture of body image and things like that. It’s really up to the reader. As long as people get all the way through it, and it makes them have an opinion, then my work is done.”

Interestingly, today’s readers are increasingly able to express their opinions about a text, and similarly to respond to them. Given how easy it is for audiences to create textual responses on their own, the original text can very easily become part of a narrative web rather than standing alone as a canonical piece of work. Not only is the role of the text changing, but so too is that of the reader: they’re no longer passive consumers of content, but rather become creators themselves, whether via short, pithy responses such as tweets or memes, or via considered, longer form responses.

“One of the great things about social media and blogging and culture and Twitter is that dialogue,” says Dan. “I think being able to discuss a work openly, and to have people respond, is an important thing to have as storytellers. You can look at something like fan-fiction, where people are so inspired and in love with what you’ve created that they want to use that as a platform for their own creation. I’m not endorsing or vilifying fan fiction in any way, but the fact that it exists shows exactly where we are; that the author doesn’t own their work. Once an author has written something they give up ownership.”

When F Scott Fitzgerald wrote The Great Gatsby, he would never have conceived of a possible sub-genre of erotic fan-fiction involving Gatsby and Nick.

“There’s some good and some bad, but overall, having readers taking ownership of that text is a great thing. If you log on to Tumblr you’ll see a million fan-fiction style posts about Dr Who, Supernatural and Sherlock. Fans will take screen-grabs; they’ll create GIFs; they’ll write fan-fiction in weird sexual ways. It’s happening in literature. It’s happening in any sort of storytelling, any kind of narrative at the moment. It’s exciting for creators, because you can put something out there that people can respond to.”

I suggest that perhaps this is the twenty-first century version of carrying on the oral storytelling traditions of old.

“People certainly seem to not only want to create their own stories, but play with already created ones.”

The idea of playing, however, suggests something ephemeral and fleeting, and I can’t help but ponder whether platforms like Creatavist are less about encouraging deep engagement with storytelling than they are about feeding our insatiable desire to multitask. Does augmenting a story with multimedia elements encourage distraction, and if so, what does this mean for the way that we consume literature?

“I think you’re satisfying the reader’s curiosity and keeping them within your story, actually. I’m notorious for putting a book down and googling something because I want to know more, and obviously that pulls me out of the story. With something like this, you can kind of pre-empt what people might want to know more about that by embedding that information in the story, and have it as something that the narrator is telling you. I don’t necessarily think that distraction is a bad thing. It just plays to our natural curiosity, and the fact that we have all this information at our fingertips. This never used to be an issue in the past, which is why narrators would often break the fourth wall and talk directly to the reader and explain something. In a way, these sorts of multimedia texts are harking back to that.”

But although in many ways multimedia platforms can be seen as, somewhat contradictorily, a modern iteration of nostalgia, I can’t help but wonder whether there’s a distinctly contemporary element that’s at play here: the notion of “show don’t tell”, which I personally find very problematic, triumphing to an extreme. As platforms such as Creatavist become more prevalent, and more sophisticated, will we begin to see a shift away from story-telling that uses words—an approach that requires some degree of linearity—in favour of one that emphasises visual formats?

Dan emphatically disagrees.

“We were discussing David Shields and the death of the novel earlier, but it’s something that I don’t particularly agree with. The novel will always exist in some form. To me the idea of an ebook is ridiculous. It’s a book. It’s in electronic form, but it’s a book. You don’t say e-song, do you? In that sense the novel format will always be there.”

What Creativist does, he says, is give an opportunity to tell stories in different ways.

“My personal take on the platform is that it’s a great opportunity for telling stories, but that it doesn’t change anything, because the stories still have to be good. The written bits always have to be written well. Yes, there’s multimedia and music, but without the writing it all falls apart. I don’t think that the craft of writing is going anywhere. We’ll always write. In truth, people probably write more than they ever have—tweets, blogs and so on—although they probably don’t think of it as writing. And although perhaps as a consumer you might see fewer words and have to do less reading, it’s not that any less writing went into creating that story.”

Dan adds that despite our preciousness over the concept of “the novel”, the novel itself is a relatively new concept, having been born from the serial.

“Dickens, for example, would write a whole heap of serials that were then collected in a volume. Now we sit down to write a novel. That’s evolved over time. There’s no one way to tell a story. What Creatavist does is to give you these tools to tell a story however you want. The next story I tell might be twenty thousand words with no video at all, or I might choose to use more video. Storytelling formats are going to evolve.”

Given the apparent tug of war between visual and written forms of storytelling, and my propensity to play devil’s advocate, I’m curious to hear Dan’s take on which is at the heart of storytelling: the word, or the image.

“I’d probably expand the ‘word’ to the text. The story is a projection in the mind of the reader or the consumer. Without the text to stimulate that, it wouldn’t exist. I’m a minimalist. I subscribe to the idea of the Hemingway iceberg theory. Showing the least amount possible and letting the reader imagine the rest. It’s not a cop-out in any way: I’m not saying that I can’t be bothered to write the whole thing. It’s an approach that lets each reader bring their own thoughts and ideas to the story. In that sense it’s a collaborative effort. Without the text the story wouldn’t exist.”

Visit Daniel Dalton’s website | Twitter | Facebook

The post Daniel Dalton on Creatavist and multimodal story-telling appeared first on Read in a Single Sitting - short books, page-turners, and books you can't put down.

By: Stephanie Campisi,

on 5/21/2013

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

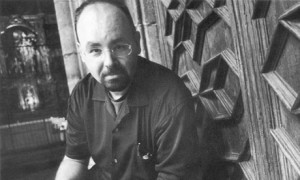

On Monday I popped along to the Wheeler Centre to see Barcelona-born, LA-based author Carlos Ruiz Zafón in conversation with local writer and broadcaster Sian Prior. As usual, I went bearing pen and paper, and took copious notes. (A video of the event will be forthcoming from the Wheeler Centre, but a sort-of-verbatim transcript never hurts.)

Prior began the conversation with an observation regarding Ruiz Zafón’s obvious passion for books as artefacts, as well as the power of stories, and how these appear as recurring motifs in his work.

Stories have always been an important part of Ruiz Zafón’s life: even as a child he was fascinated by the concept of storytelling, and by all types of stories, between which he never differentiated as a young reader. Everything was, to him, a “big bag of stories”. He was intrigued not just by stories, but by their structure and architecture, and was always toying with them and analysing them to determine how they worked. It was only later that he began to differentiate between different forms of storytelling–for example between books, graphic novels, and films–as well as the different genres within these forms.

As seems to be surprisingly often the case for bookish individuals, Ruiz Zafón was the only keen reader in a family that was generally not especially interested in the arts and entertainment. As such, he was always seeking out books wherever he could find them, an approach to which he partly contributes his omnivorous reading diet. He would read through his father’s book collection, which comprised large sets of beautifully bound, poorly printed classics and heavy books–the types of books bought for display rather than for reading, and which Ruiz Zafón joked were probably bought by the metre. In addition to these, he would also read the Marvel comic books that his grandmother would buy for him.

A book is a gothic cathedral of words.

Prior commented that this kind of genre agnosticism is evident in Ruiz Zafón’s own work, which mixes genres and stylistic elements in a way that is redolent of a labyrinth.

Ruiz Zafón agreed, saying that he relishes working with complex, challenging systems and developing labyrinthine, layered works. His approach to plotting is one that takes time to coalesce into something concrete, involving as it does a good deal of time spent on thinking and musing over various themes, elements and characters and the way that they will overlap. It’s also one that requires re-plotting and re-working: no matter how much time is spent on developing these things, everything needs to be continually redrawn as the book progresses.

It’s a system that has evolved over time, however. When he first started out, he tended to work without much of a plan, and would let himself reach the end of a work before going back to fix problems or analyse the devices he had incorporated. Now, however, he thinks of plotting a book as something akin to building a gothic cathedral–a complex structure made from words. It’s essential to keep restructuring and reworking until the final result is as close as possible to the original idea.

A good deal of planning was required when developing the four-book Shadow of the Wind cycle, which he originally conceived of as a single, epic volume. Having got about thirty or pages into the manuscript of the first volume, he realised that the result would be something so monstrous that it would probably be physically impossible to shelve it (and, he joked, there was the risk that people might perish under the weight of the thing). He didn’t, however, want to write the cycle as a sequential series or 19th Century-style saga, but rather as four books, each representing a different entry into the “labyrinth” of an overarching narrative, and thus creating a variety of different possible reading experiences.

The aim was to deconstruct storytelling, to play around with it, and to make storytelling itself the heart of the story: he wanted to explore readers’ often complex relationships with books, how genres and so on work, and to combine it all using whatever tricks were available to him as an author. All of this was pinned against the skeleton of the classic saga trope of a young boy growing up and trying to find his place in the world.

Ruiz Zafón believes firmly that character should always usurp plot, and that good plots arise from good characters, not the other way around. Each of the characters in The Shadow of the Wind saga has a variety of roles to play. Fermín, for example, is an homage to the picaresque tradition. He’s the fool, the madman, the jester, but at the same time, has the freedom to speak the truth when no one else can. He’s the moral centre of the books even though he’s not necessarily going to be taken seriously by the reader due to his strange and outlandish theories. But these are theories and are always well-meant: he always attempts to be a decent person in a profoundly decent world, something at which all of the other characters eventually fail.

To destroy books is to destroy the mind.

Prior suggested that in the books there’s a sense of books and reading being in a way dangerous, and Ruiz Zafón concurred, saying that books and knowledge can be a curse for some. You can fall in love with literature, he said, but literature never falls in love with you. He added that books are a repository of beauty, knowledge, memory and identity, and that they help us understand who were are. It’s this power that makes them so very dangerous in the eyes of some–to the extent that some groups seek to destroy books, hoping that in doing so they can destroy all that books represent.

When you destroy language, you destroy identity. And to destroy books is to destroy the mind.

Prior commented on the connection between language, culture and place, and asked to what extent the cycle is an homage to Barcelona, a place with which tourists so famously fall in love. Ruiz Zafón responded that Barcelona is his mother, something so key to his identity and experience that he cannot see it in the way that a tourist does. Rather, he seeks to get to the true heart of the city, to explore the truths of its characters. He has a conflicted relationship with the city, seeing it as he does through the eyes of a native, but like all writers he needs to engage with it in order to come to terms with his roots and origins. He is, though, very aware that it’s impossible to portray a city exactly as it is: there are many Barcelonas.

When asked about both the difficult history of Barcelona and the research that goes into his books, Ruiz Zafón responded by saying that he believes that most residents of the city today don’t necessarily think, at least deliberately and consciously, of events such as the civil war or WWII, and that they’re disconnected from the past in a way, having not been alive during those times. He says that this is something that’s true for all of Europe: “The end of the world happened there sixty years ago, but now it’s all Benetton shops.”

However, even so, it’s impossible to escape the history of a place. As someone who’s a natural autodidact, he’s always seeking to learn more about his home city, and about the world generally. Rather than researching something specifically, for specific purposes, he tends to simply read widely and supplement this reading with his own deep knowledge of specific things. He would not write about something about which he’d need to begin from scratch–for example, he would be shy writing about Melbourne as not only does he not know the city, he feels as though he could never know it.

Interestingly, the majority of The Shadow of the Wind cycle was not written in Barcelona, but rather in Los Angeles, where Ruiz Zafón prefers to write, believing that he is more productive and creative there. The Angel’s Game, however, was written in Barcelona, and he believes that it shows: place inevitably taints the writing. He feels, too, that the books are not at all Spanish in feel–even the Barcelona of the books is very much a construct–but rather have a very LA-style sensibility, something that was an issue when he attempted to sell the books into Spain, which saw them as entirely “un-Spanish” and outside the Spanish literary tradition. It wasn’t until the books become hugely successful that they were gradually accepted into the Spanish literary scene.

Young readers are sincere and passionate, but they’re also merciless.

Prior drew the conversation around to matters of audience, noting that although Ruiz Zafón’s first few books were for young readers he seems to write now for an audience that’s more adult-oriented, or that at least has crossover appeal. Ruiz Zafón rather sheepishly explained that he found himself writing for young readers after his first book won a prestigious YA award that came with a large monetary prize. He was all too aware of how difficult it was to make a living as an author, and so felt in a way that he had to pursue this path, even though in his heart he had never wanted to write within a specific genre or for a carefully delineated audience. Perhaps out of conservatism or cowardliness he continued writing young adult books until he realised that he was betraying not only himself, but his readers by doing so.

He noted, though, that when he first began writing for young readers, the market was nothing like how it is now: there was no internet, and no young adult category. There were certainly no paranormal romance shelves, he said, lamenting about such books, “man, it’s the end of the world. We have like six months.” However, though YA isn’t his genre as such, he believes that young readers can be among the best readers an author can have. They’re sincere and passionate, but they’re also merciless. Unlike adult readers, they can’t be swayed by reviews or awards, and will put down a book immediately if it doesn’t grab them.

The conversation steered around to the place of the bookshop in today’s world, something that is of interest to Ruiz Zafón given the subject matter of his books. When Prior suggested that we might be seeing the “end” of the bookshop, Ruiz Zafón disagreed, arguing that although many of today’s bookshops will disappear, others will appear. The problem is, he says, we have a habit of thinking of ourselves as the end of history, when really we’re merely passing through. Everything changes, and will change even in our lifetimes. Publishing, for example, has changed dramatically over the past century, and what we think of as “publishing” or “bookselling” is really only a brief moment of transition in a changing model.

Beauty and knowledge – the redeemers.

Whether books, stories, or minds survive, however, is something that is up to us. Ruiz Zafón believes that there are two redeeming values in the world: beauty and knowledge.

Support Read in a Single Sitting by purchasing Carlos Ruiz Zafón’s books using one of the affiliate links below:

Amazon | Book Depository UK | Book Depository USA | Booktopia

or support your local independent.

Books by Carlos Ruiz Zafón:

The post Event Summary: Carlos Ruiz Zafón in conversation at the Wheeler Centre appeared first on Read in a Single Sitting - short books, page-turners, and books you can't put down.

By: Stephanie Campisi,

on 5/13/2013

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

“If [the myth of Sisyphus] is tragic, that is because its hero is conscious. Where would his torture be, indeed, if at every step the hope of succeeding upheld him?” writes Camus in The Myth of Sisyphus, in which he grapples with whether–and if so, how–it’s possible to exist in a life that is without meaning.

However, it’s in the following that it becomes apparent that Camus’ modernity differs somewhat from our own:

“The workman of today works every day in his life at the same tasks, and this fate is no less absurd. But it is tragic only at the rare moments when it becomes conscious.”

Camus’ use of “rare” to describe our awareness of the absurdity of our experience rings a warning bell for me; it seems to flag a significant shift in our social identity and ideology since the publication of this essay. Contexts change, and so too, it seems, does the applicability of the Camusian argument.

(Perhaps this is an odd little counterpoint to Haruki Murakami’s claim that “while there are no undying works, on principle there can be no undying translations“. It’s not just the linguistic side of things that shifts over time, but also the sociolinguistic element. Maybe “translations” here could be expanded to mean “interpretations”.)

Though I take many of Camus’ points about the absurd experience of life, I would suggest that the way in which the Camusian “revolt” against this very thing has played out in the present day world differs from the case he has argued for it.

I speak, of course, of the rise of the hipster.

I’ll get to that in the moment.

Camus argues that absurdity arises, and is acknowledged, when spiritual dimensions are stripped away and we are left to face life purely on its own terms. With the egress of organised religion from the western world (the exception, perhaps, being the weirdly puritanical USA), the emphasis on the individual over the collective, and the shift towards a society that emphasises intellectual labour, it’s surely the case that although existence is no less absurd, our awareness of such absurdity is on the rise.

We’re a society primed to recognise the absurdity of our existence. Hence, no doubt, the ubiquity of terms such as “quarter-life crisis”, “mid-life crisis”, “identity crisis” and so on.

But acknowledgement is only the beginning. Far more profound is the way in which people respond to this recognition of the absurd nature of life. Camus highlights several representative exemplars of possible such reactions, all of which really entail the same thing, an idea summed up in the following: “What counts is not the best living but the most living.” We have the Don Juan character who loses himself in passionate affairs, the actor who lives myriad lives in quick succession, and the warrior who sacrifices thought for action.

It’s not hard to see contemporary equivalents in the commercial Don Juanism that is the drive for the consumption of goods, or the extraordinary amounts of media that we take in, or the tendency towards over-scheduling and dabbling.

There’s an ephemerality in all of these examples, an existential lightness that at first glance seems to conflict with the fate of our titular Sisyphus, a man who suffers beneath the indignity of endless, backbreaking labour, a man cursed to strive forever towards a goal that cannot be obtained. Sisyphus’s task, after all, is one imposed from without, unlike those engaged in by the characters Camus describes. Sisyphus is further distanced from these individuals by the fact that he is immortal, and his fate is an eternal one. This would seem to set the Sisyphean case at odds with Camus’ argument of the absurdity of life, which can’t exist without the prospect of death.

But immortality is, by its very nature, all about death. By removing it from the equation it looms even larger than before: it’s there by virtue of its not being there. It’s a chilling notion, because by removing such an important boundary from life, it’s hard to imagine what’s left. When everything becomes infinite, everything becomes nothing. Given that he is cursed to repeat his boulder-carrying task for all eternity, it would seem that Sisyphus’s possible responses are few. All that is possible is an emotional response. Happiness, Camus puts forth, is one.

Fear, brought about by this ontological (dear nonexistent God, did I just write “ontological”?) crisis, is the other. It’s an emotion that I think can manifest in a variety of ways, including the Camusian examples I’ve reprised above–although these, I suppose, might well be motivated by happiness as well.

My thought is that in today’s world, or at least amongst my moustachioed, chai latte-sipping contemporaries, this fear doesn’t manifest itself in the sort of engagement we see in the aforementioned examples, but rather the opposite. It shows up in disaffection, disengagement, and that oh-so-hipster sense of irony. Camus touches on this when he writes: “for the absurd man it is not a matter of explaining and solving, but of experiencing and describing. Everything begins with lucid indifference.”

But while Camus argues for “revolt” in the form of railing against the absurd life by throwing oneself into the moment, we rail against our absurd existence through withdrawal and irony. While it’s suggested in the essay that there is something profound to be found within the Sisyphean existence, something that can arise out of the redefining and re-envisaging of failure, an ironic existence further narrows the sphere of our experience. Rather than “the most living”, we seem to seek out the opposite.

Curiously, an ironic stance is both defeatist and nihilistic, but is also retrospectively oriented as well: though Camus’ absurd person lives in the moment, an ironic existence seeks to disconnect from the present, and necessarily uses the past for a point of comparison.

But I can’t help but wonder whether that’s the point of it. Where Sisyphus embraces the absurd life, the ironic response seems to try to deny that the acknowledgement of the absurdity of existence ever occurred in the first place. Is our revolt one of fearful non-revolt and the revocation of acknowledgement? This would seem to jive with Camus’ assertion that “living an experience, a particular fate, is accepting it fully.”

But is it too late? Is irony enough to provide us with the existential time-travel that we need to wipe clean the absurdist slate once we’ve chalked all over it? It would seem not, according to Camus, who writes:

“A man is always a prey to his truths. Once he has admitted them, he cannot free himself from them. He must pay something. A man who has become conscious of the absurd is for ever bound to it.”

And yet, we are told: “there is no fate that cannot be surmounted by scorn.”

Like it or not, we are all the modern day Sisyphus. But we are an army of Sisyphuses who are more likely to ironically Instagram our boulders than carry them up a hill.

See also our post on The Outsider

Support Read in a Single Sitting by purchasing The Myth of Sisyphus using one of the affiliate links below:

Amazon | Book Depository UK | Book Depository USA | Booktopia

or support your local independent.

Other books by Albert Camus:

The post Hipsters, irony and The Myth of Sisyphus by Albert Camus appeared first on Read in a Single Sitting - short books, page-turners, and books you can't put down.

By: Stephanie Campisi,

on 5/7/2013

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

Of late it seems that I am being haunted by intertextuality. Each book that I pick up seems to slot into the vast Connect Four board of hermeneutics that is my reading life, and with everything I read, I find my to-read list growing ever broader and ever deeper.

I seem to be at a stage in my reading where so many unknown unknowns are swiftly becoming known unknowns. It’s a tantalising, maddening point to reach, and my reading has slowed dramatically as I find myself digging not just more deeply into individual works, but in my attempts to see how they connect to each other.

While reading Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus, which I read just after Chaim Potok’s In the Beginning, I happened across an article on breath and breathing by Sebastian Normandin that somehow tied the concepts in the two books together for me.

All three texts evoke in me a mental image of a pendulum, an image that I think is quite aptly applied to where I find myself in my own reading and writing and desire for understanding.

In Sisyphus’s endlessly repeating task, as in breathing, as in the quest for knowledge, there is a precipice, a turning point, that must be negotiated. There is the point where Sisyphus’s boulder reaches its gravitational apogee, at which it will begin to descend again; there is also the point where Sisyphus pauses, reflects, then commits to beginning his task anew. The same sequence occurs with each breath that we take.

But each instance can never be the exact same beginning as the last one. You might argue that all beginnings are turning points, and all turning points are beginnings. Each change, each realisation, each opportunity for growth involves seeing the boulder tumble back down, ready to be pushed up again to that cruelly insurmountable precipice.

In the Beginning is filled with these moments. A lyrical, formidable bildungsroman, it’s many things, but for me it’s most saliently a celebration of the courage involved in not just recognising a new branch in the ever unspooling fractal of one’s intellectual life, but in deciding to take this branch.

It’s a celebration of curiosity, of the sometimes destructive human thirst for knowledge and understanding, of the breath-stealing moment that is standing at that edge and wondering just where the pendulum will take you.

“All beginnings are hard,” writes narrator David. “Especially a beginning that you make by yourself. That’s the hardest beginning of all.”

Indeed, David’s battle is one that bears many similarities to that of Sisyphus–and Camus would surely quirk an eyebrow at the absurdity (in the Camus sense) of a young Jewish boy devoting a life to biblical study. It’s an absurdity that Potok acknowledges in the narrative through the unanticipated precipices that he throws David’s way:

“I have accidents all the time. I killed a canary and a dog by accident. And I fall and hurt myself. And I almost started a fire once in our kitchen. And I almost fell out of my window…Every night I dream about having accidents…sometimes I think there’s something wrong with me.”

But like Sisyphus, David persists despite the many and myriad obstacles in his way. When he muses: ”when you didn’t expect something to happen and it happened, that was also an accident…” it’s hard not to think about this in terms of unknowns and turning points. Accidents are, obviously, an outcome of sorts, and therefore represent a turning point; a possibility for a new beginning or that moment whereupon a Sisyphean hero takes that breath and makes a decision to continue.

By persisting in his search for knowledge in the face of these accidents, David is constantly reasserting his humanity. It’s those who don’t struggle, who don’t seek those turning points who slip away into nothingness, into intellectual and spiritual stagnation:

“What’s a sacred heart?” David asks at one point, to which he receives the response: ”I don’t know. I don’t interest myself in such matters.”

Apathy requires disengagement, a stepping away from involvement. It’s the safe route, but what’s the point of it? Sisyphus might, after all, simply step to one side and let his boulder slip away and come to rest. But then what? If he did so, who would he be? What would be his purpose? What would he have achieved but that single event?

“Anyone who knows very clearly what he’s doing with his life will have people who dislike him,” David is told. Perhaps what is meant here is not dislike so much as lack of understanding, of appreciation.

I think that the reason that intellectual journeys are so challenging to appreciate and comprehend is their lack of resolution, of a clear outcome. Learning is a process, and it’s a strange, cyclical, self-referential one, much like Sisyphus’s lifelong task. It is its own reward.

During a tango workshop a few weeks ago, my teacher mentioned that everything comes back to basics, that it’s all about the walk. Every time she takes a step, she’s achieving something: she’s bringing a new perspective, or experience, or simple reaffirmation to this most basic element of dancing.

It’s an ongoing effort to refine, to improve, to seek a change.

Camus and Potok have something fundamental in common. Camus tells us to imagine Sisyphus happy, and perhaps he has a point. The Sisyphean existence isn’t devoid of meaning. In fact, it’s about finding meaning.

As David’s teacher puts it:

“A shallow mind is a sin against God. A man who does not struggle is a fool.”

It’s a surprising achievement to realise just how much you don’t know, and it’s kind of exhilarating to stand there with a boulder, take a deep breath, and seek one of many, many new beginnings.

As a reader, I’m a very, very happy Sisyphus.

Support Read in a Single Sitting by purchasing In the Beginning using one of the affiliate links below:

Amazon | Book Depository UK | Book Depository USA | Booktopia

or support your local independent.

Other books by Chaim Potok:

The post On Sisyphus, Camus, knowledge and Chaim Potok’s In The Beginning appeared first on Read in a Single Sitting - short books, page-turners, and books you can't put down.

By: Stephanie Campisi,

on 4/23/2013

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

Over the course of my last few reviews I’ve been considering the role of the author as narrator and as character, and the degree to which authorial insertion is, to the mind of the reader, assumed to be inalienable. In large part this has been inspired by the narrator character–who is, perhaps, the author himself–in Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being and his/her thoughts regarding the use of characters as an author’s possible selves.

The idea has continued to haunt me, and in my reading recently I’ve been pondering the inextricability of the author and their work. I do think that there’s a winking fallaciousness to Kundera’s statement, and it’s to do with the slippery slope and extrapolation that’s inherent in the idea of possibility. There are, obviously, degrees of remoteness involved in all of this. An author might create a character who is in every way the author’s image (or at least as near as possible–the character can never be the author, but only ever a facsimile of the author). This would be an example of a close possible self. Of course, an author might create someone who is their polar opposite, but for all this dichotomy, this character would still remain a possible self, merely a distant one. After all, it’s impossible to write without using oneself as a reference.

However, I do think that there is a tendency for readers, unless told otherwise, to see an author’s characters as close possible selves. Camus, in The Myth of Sisyphus, which I’m presently reading, says, “though I have seen the same actor a hundred times, I shall not for that reason know him any better personally. Yet if I add up the heroes he has personified and if I say that I know him a little better at the hundredth character counted off, this will be felt to contain an element of truth.” I think that this is particularly true of narrator characters. (For an example of this, you need only see my lack of certainty above regarding the identity of the narrator character in the Kundera.)

Where, of course, this conflation of author and character becomes a problem is when the character exhibits morally questionable traits.

I read with interest some months ago an interview with Junot Diaz regarding his writing of a misogynistic character in such a way that he as an author would not be seen as tacitly condoning the character’s sexism, but that would not signpost his own beliefs in such a way that it would break into the narrative:

“If it’s too brutal and too obvious then it becomes allegorical, becomes a parable, becomes kind of a moral tale. You want to make it subtle enough so that there are arguments like this….For the kind of sophisticated art I’m interested in the larger structural rebuke has to be so subtle that it has to be distributed at an almost sub-atomic level. Otherwise, you fall into the kind of preachy, moralistic fable that I don’t think makes for good literature.”

This line of moral ambiguity is one along which Nabokov carefully treads in his masterpiece Lolita, and throughout the book we see a careful distancing of author, narrator, and even character in order to achieve a separation of author and work. That the novel is bookended by an explanatory, absolving foreword from a fictional character posing as the author, and an afterword by Nabokov himself speaks volumes; there is also further distance created in my edition (The Everyman’s Library edition) by the inclusion of a lengthy introductory essay. We see an additional obscuring of identity and therefore of self by the fact that Humbert is itself a pseudonym, as is the surname “Haze”, given to Lolita and her family. These structural elements are probably the most overt attempts at separating the author and work, but Lolita is rife with them.

Take, for example, the book’s self-consciously literary approach, with its three-act structure and its narrative artifice. The various deaths and disappearances of Humbert’s lovers feel deliberate and unnatural, carefully shoehorned into the plot to create a sense of the created rather than the naturally arising. Characters and situations appear as obstacles or illustrative points less than they do organic explorations of real life, the effect resulting in a sort of moral cushioning, particularly when we consider the book as being framed within the context of the introductory foreword from a “John Ray Jr, PhD”, with its placatory remarks about the text being a “lesson” or a “warning”.