new posts in all blogs

Viewing Blog: Yahoo! 360, Most Recent at Top

Results 1 - 25 of 122

tales, myths, children's books, illustration

Statistics for Yahoo! 360

Number of Readers that added this blog to their MyJacketFlap: 1

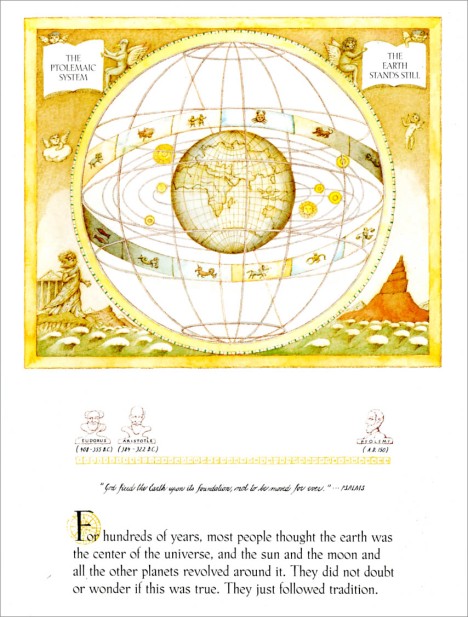

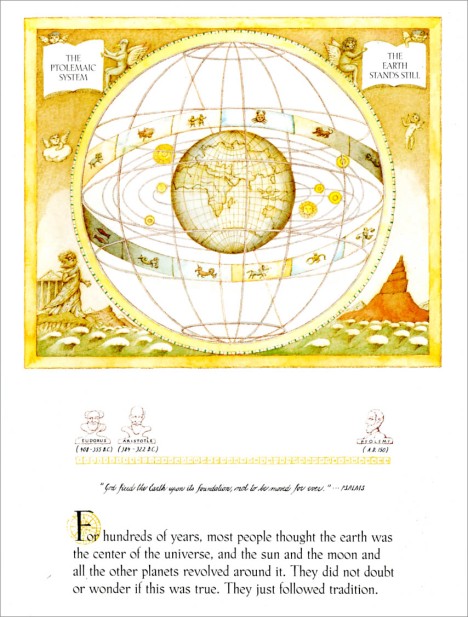

I love it when I’m teaching science or maths and there are stories to tell, stories that unfold some piece of understanding and something human at the same time. Sometimes what humanity has learnt can be recapitulated for an individual learner, and the two syncronise really well.

Such is the case with our work on Galileo this term, which connects really closely with some of the things to learn about forces.

It’s even better if there are actual story-book stories to read. Illustrated ones even. And there are. Three that I found and read with the class, each of them a gem.

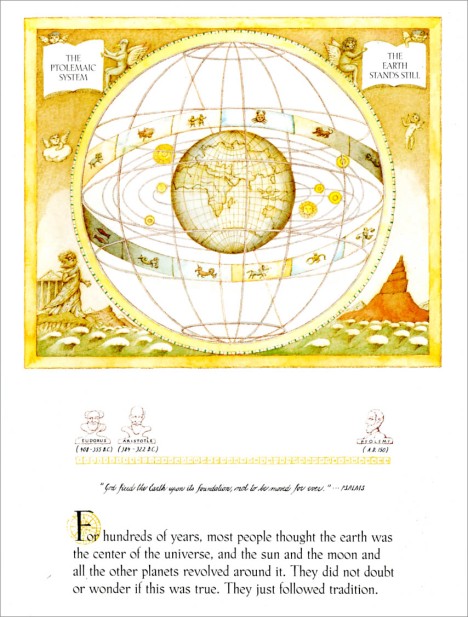

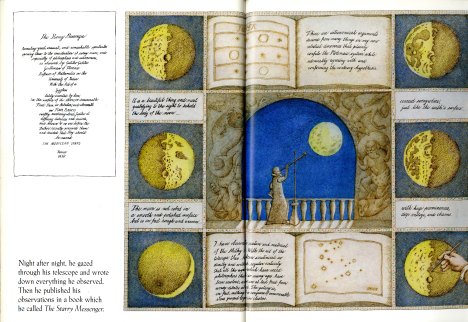

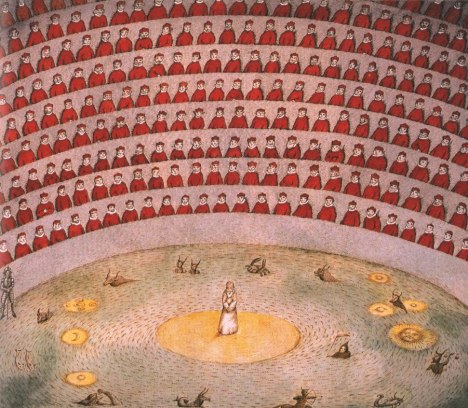

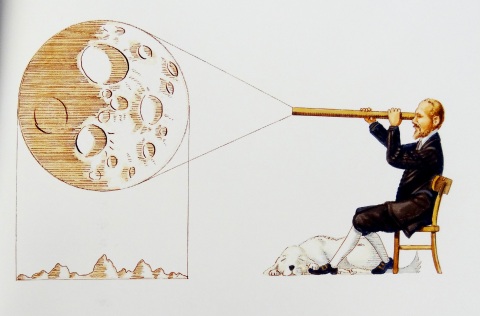

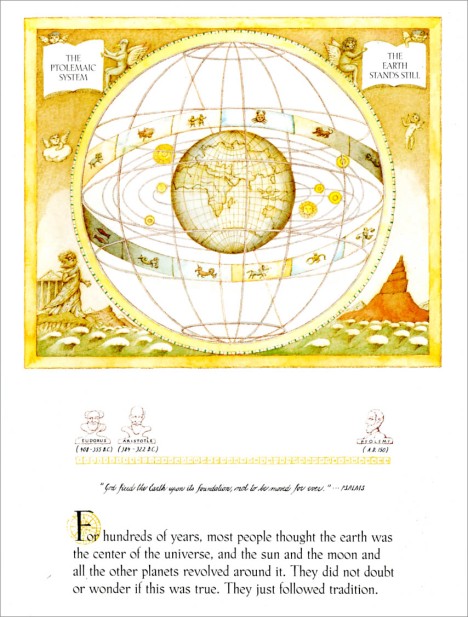

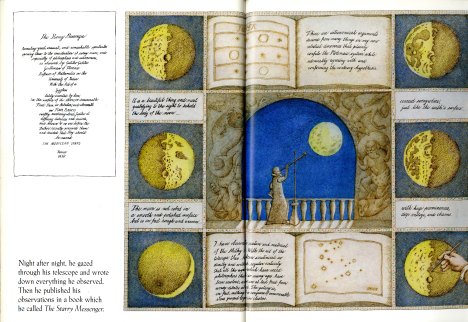

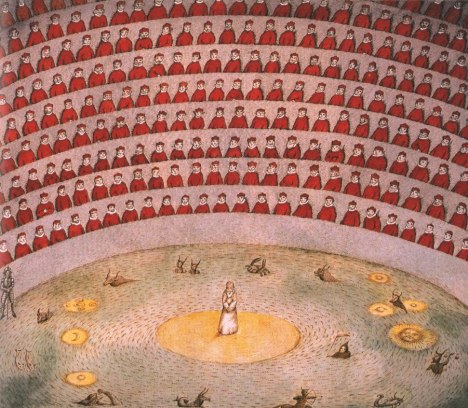

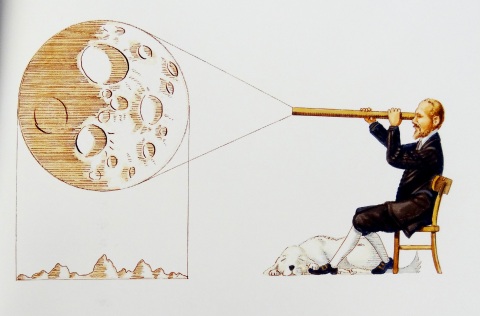

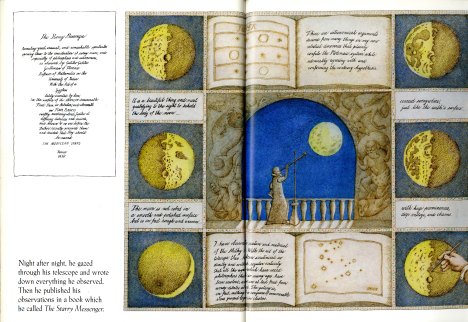

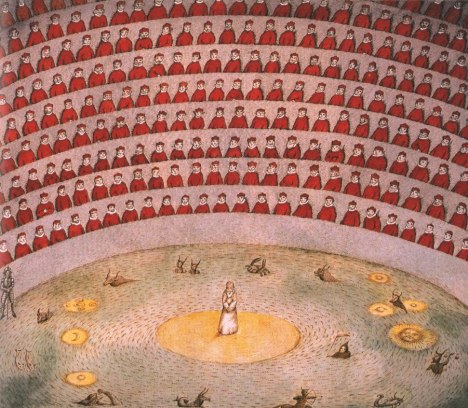

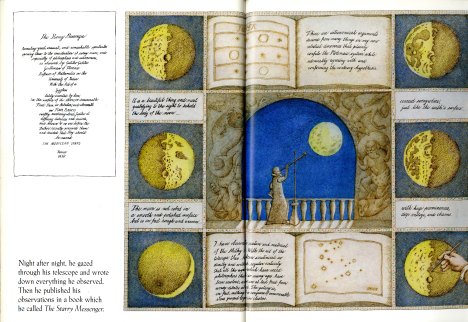

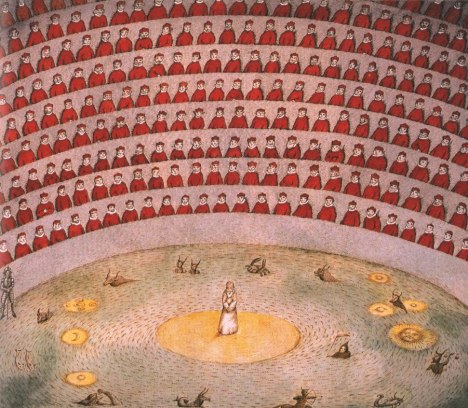

Peter Sis’s Starry Messenger is a song of praise to Galileo. It has a surreal feel and the pictures are loaded with metaphor.

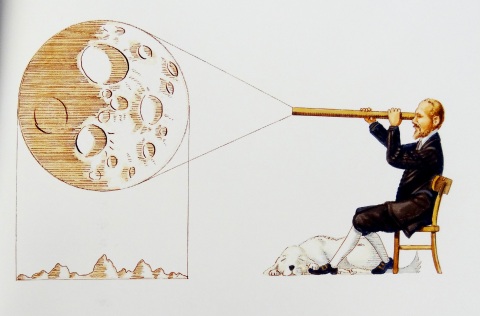

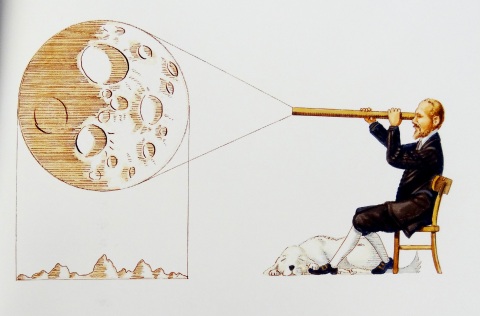

Galileo’s Journal written by Jeanne Pettenati and illustrated by Paolo Rui, tells the story of Galileo’s discovery of the moons of Jupiter in 1609 – 1610.

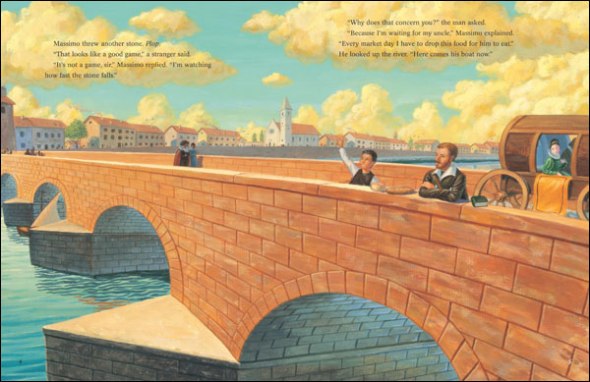

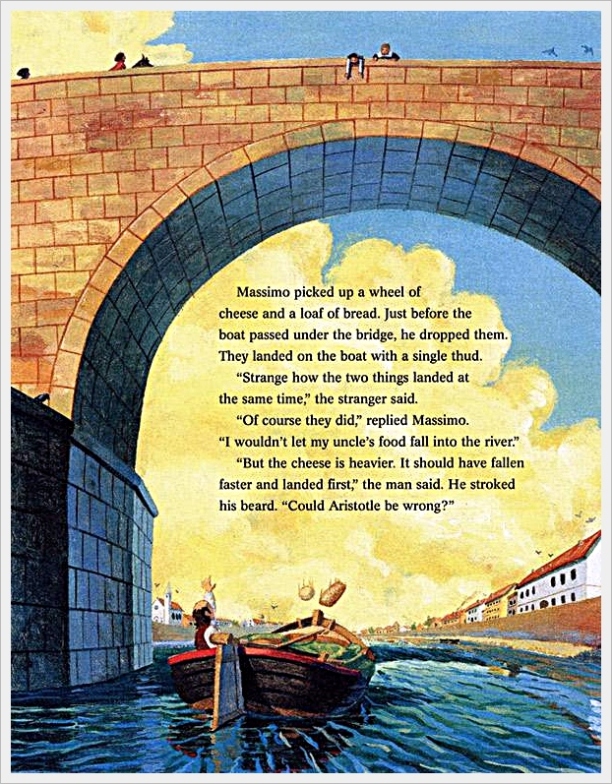

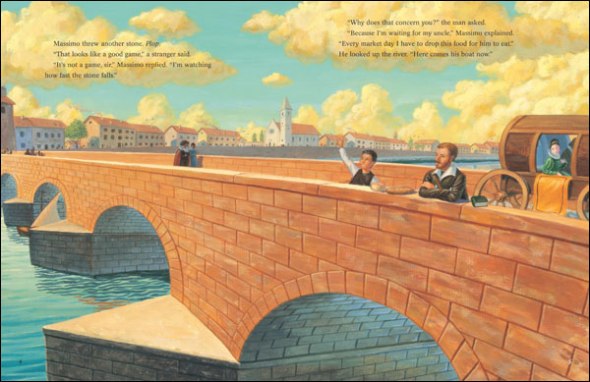

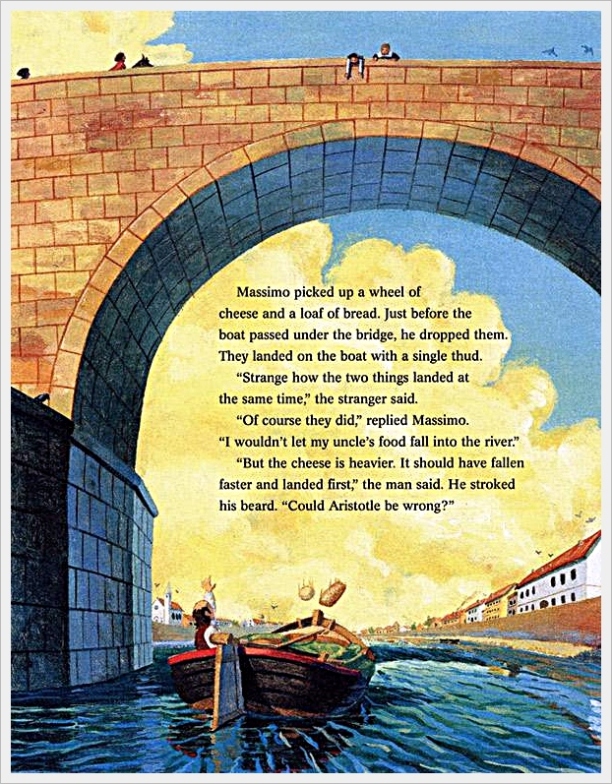

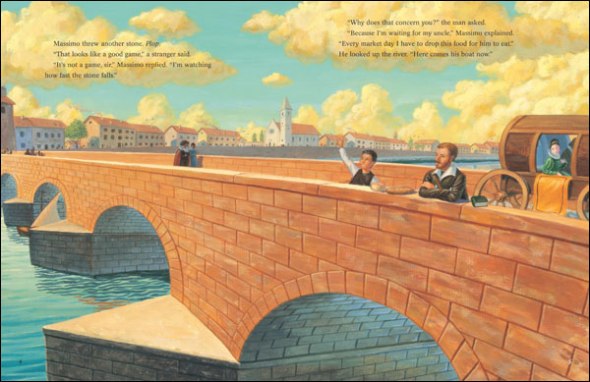

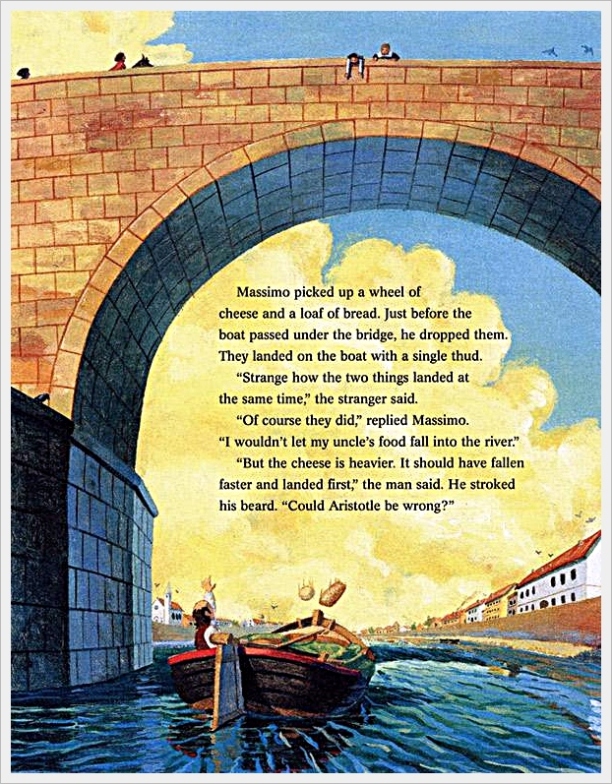

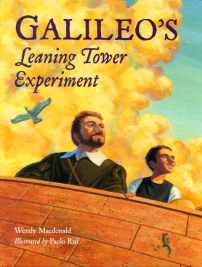

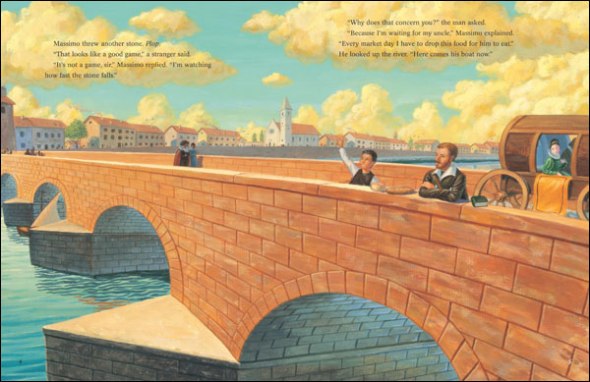

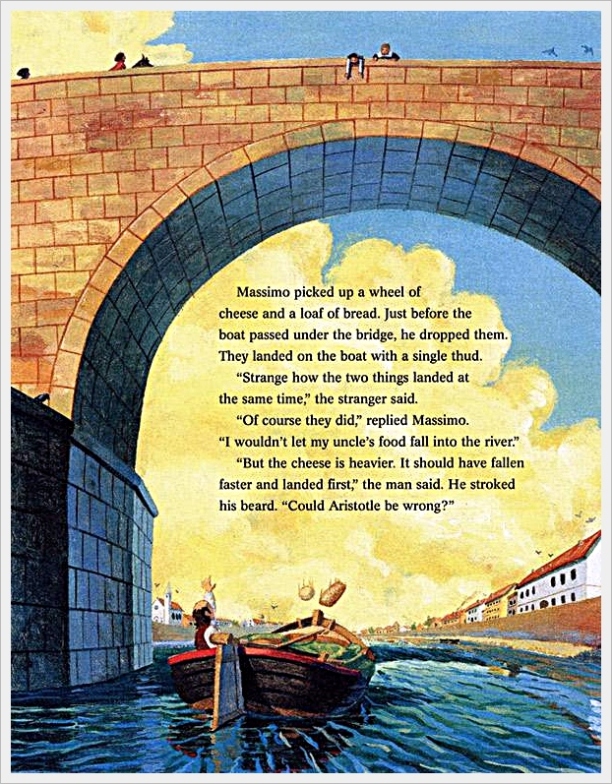

And Galileo’s Leaning Tower Experiment, written by Wendy Macdonald and again illustrated by Paolo Rui, tells the story of a little boy from Pisa called Massimo who meets Professor Galileo on the bridge while dropping bread and cheese to his uncle.

So great to find these books that, in different ways, bring the story of Galileo, and his science, to life!

I love it when I’m teaching science or maths and there are stories to tell, stories that unfold some piece of understanding and something human at the same time. Sometimes what humanity has learnt can be recapitulated for an individual learner, and the two syncronise really well.

Such is the case with our work on Galileo this term, which connects really closely with some of the things to learn about forces.

It’s even better if there are actual story-book stories to read. Illustrated ones even. And there are. Three that I found and read with the class, each of them a gem.

Peter Sis’s Starry Messenger is a song of praise to Galileo. It has a surreal feel and the pictures are loaded with metaphor.

Galileo’s Journal written by Jeanne Pettenati and illustrated by Paolo Rui, tells the story of Galileo’s discovery of the moons of Jupiter in 1609 – 1610.

And Galileo’s Leaning Tower Experiment, written by Wendy Macdonald and again illustrated by Paolo Rui, tells the story of a little boy from Pisa called Massimo who meets Professor Galileo on the bridge while dropping bread and cheese to his uncle.

So great to find these books that, in different ways, bring the story of Galileo, and his science, to life!

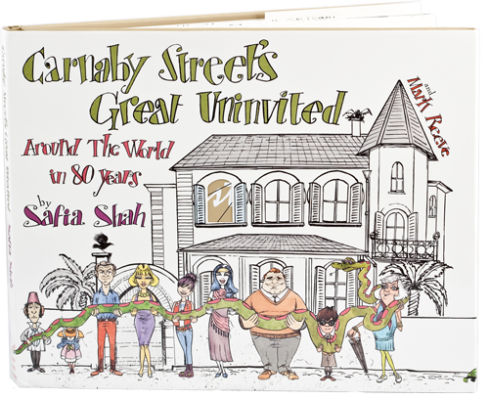

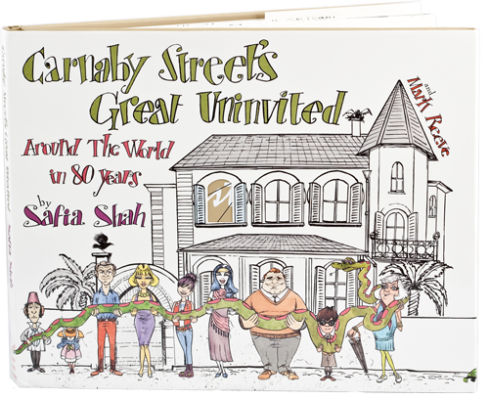

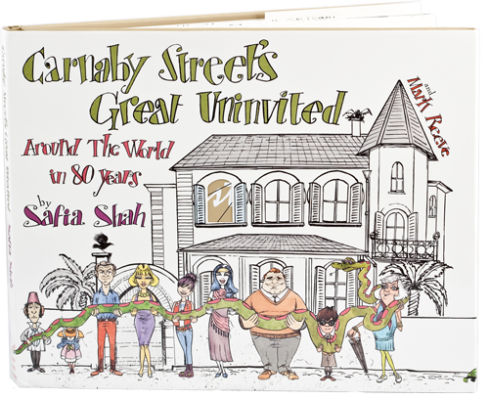

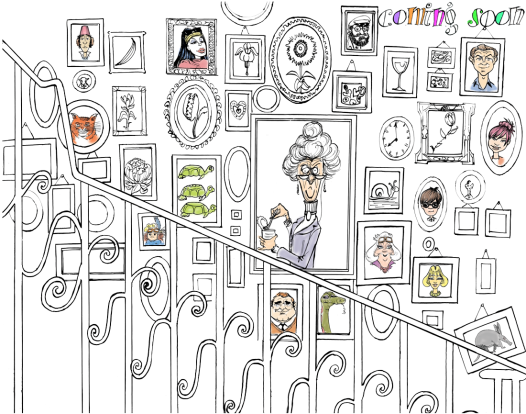

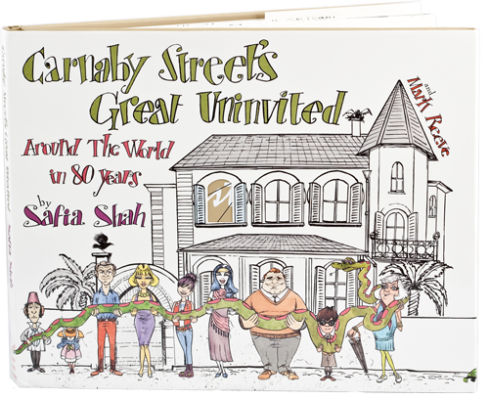

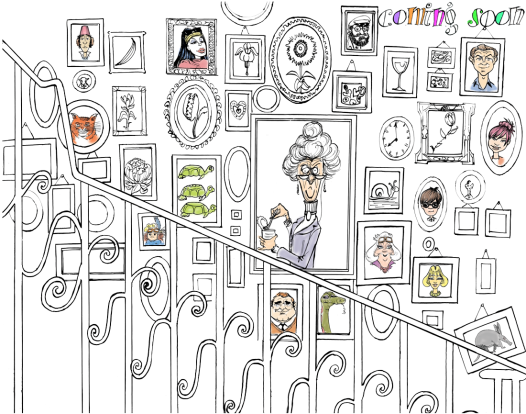

Safia Shah and Mark Reeve’s Carnaby Street is a rumbustuous maelstrom of a book, a book of unexpectedly-arriving eccentric relatives, knit-offs (maths-and-sun-loving mum wins) and unlikely cuisine.

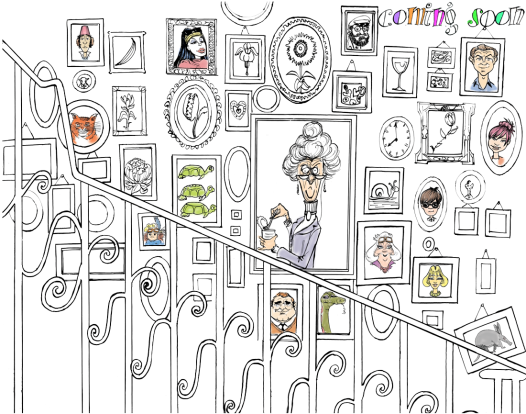

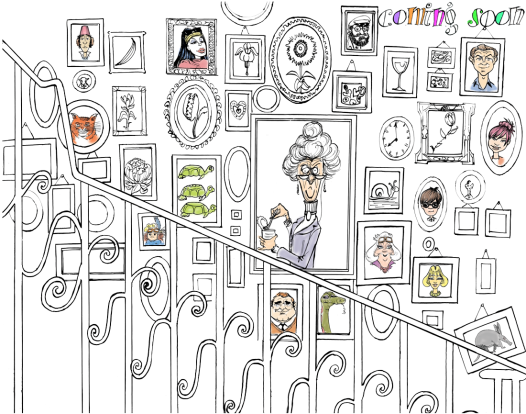

With its dizzying cast of characters, both animal and human, and its love of almost-lost locutions, it’s a book where it’s a delight to get lost in the details, which Mark Reeve brings to life brilliantly.

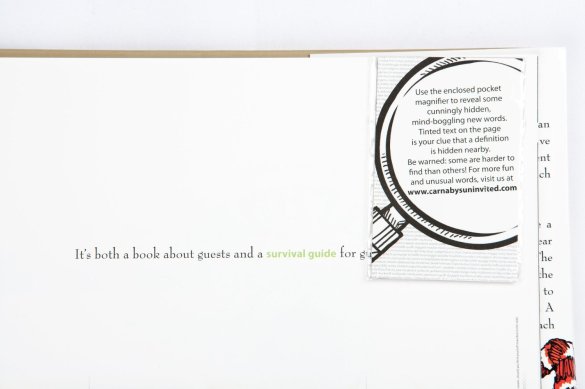

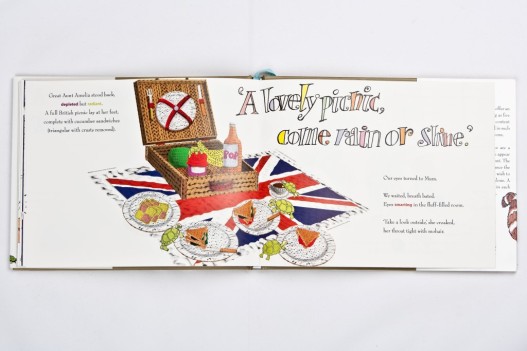

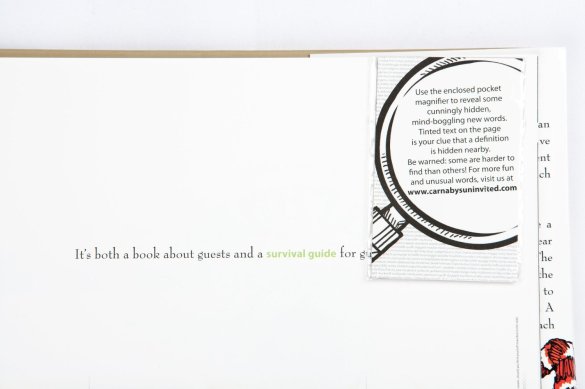

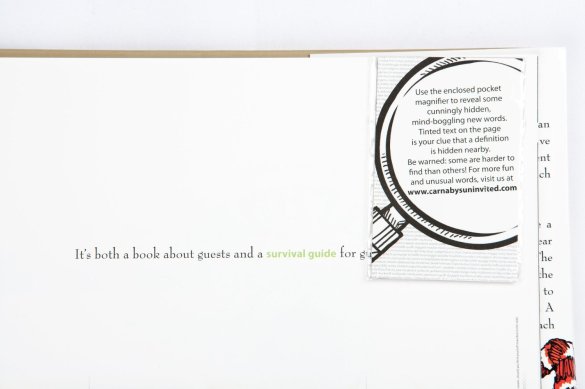

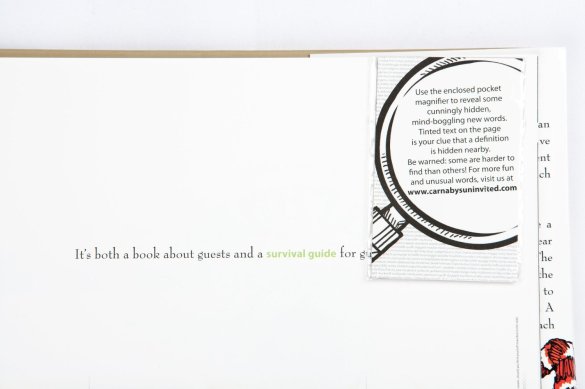

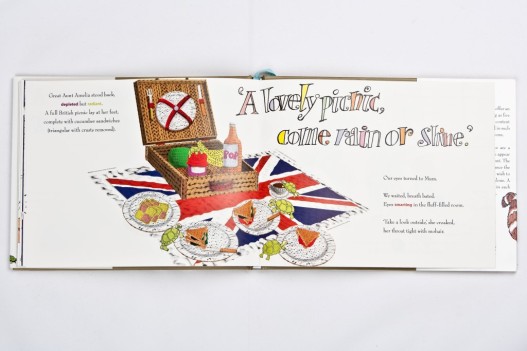

And, it’s accessorized! There’s a credit-card sized magnifying glass, for looking at the really small details, and a ribboned bookmark for… well for bookmarking (without the possibility of losing the bookmark). You might want to bookmark this page for instance:

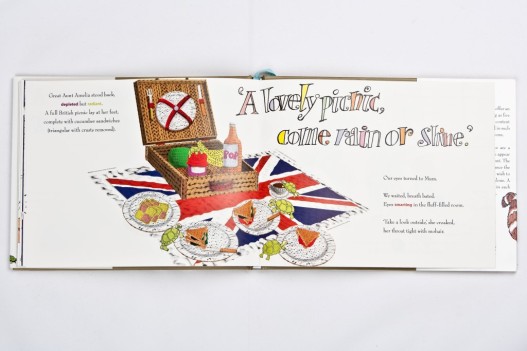

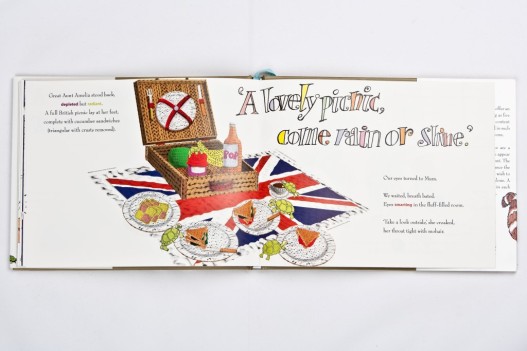

It depicts a knitted picnic. Unlikely you’d think, but then the book has led to a knitted garb for a London cab.

Here’s Safia Shah talking about the book:

Safia Shah and Mark Reeve’s Carnaby Street is a rumbustuous maelstrom of a book, a book of unexpectedly-arriving eccentric relatives, knit-offs (maths-and-sun-loving mum wins) and unlikely cuisine.

With its dizzying cast of characters, both animal and human, and its love of almost-lost locutions, it’s a book where it’s a delight to get lost in the details, which Mark Reeve brings to life brilliantly.

And, it’s accessorized! There’s a credit-card sized magnifying glass, for looking at the really small details, and a ribboned bookmark for… well for bookmarking (without the possibility of losing the bookmark). You might want to bookmark this page for instance:

It depicts a knitted picnic. Unlikely you’d think, but then the book has led to a knitted garb for a London cab.

Here’s Safia Shah talking about the book:

By:

simonsterg,

on 7/24/2013

Blog:

Yahoo! 360

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

children,

Illustration,

storytelling,

book,

stories,

cat,

Ian McEwan,

Tales,

Anthony Browne,

Add a tag

I’m teaching Year 4 next year (8 and 9 year olds). So I’ve started to read books that they might like.

I’m teaching Year 4 next year (8 and 9 year olds). So I’ve started to read books that they might like.

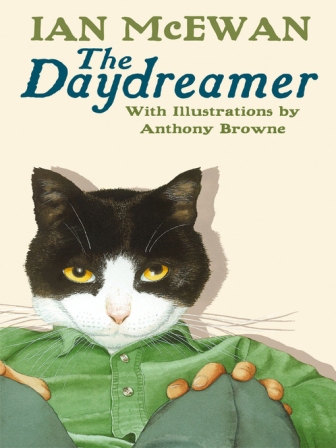

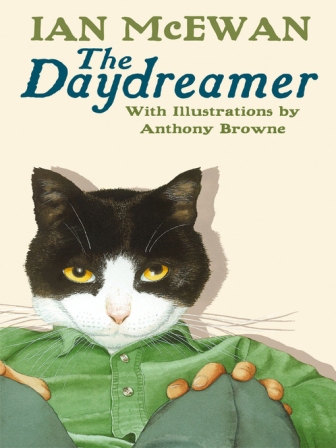

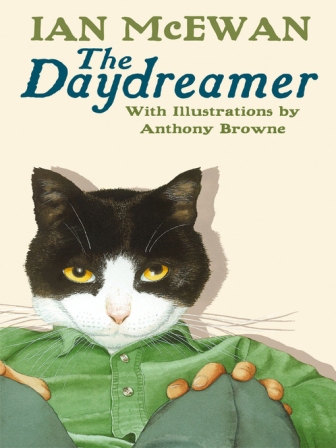

I like Ian McEwan’s The Daydreamer a lot, though maybe it’s a bit too old for most Y4 children. Why too old? Perhaps the element of threat. But then again, maybe it’s OK…

It’s a book about a young boy who’s a daydreamer, dreaming about transformations.

My purpose is to tell of bodies which have been transformed into shapes of a different kind.

Ovid, Metamorphoses

So, in the wonderful chapter called The Cat, Peter discovers something unexpected about his cat:

Looking down through the fur, and parting it with the tips of his fingers ,he saw that he had opened up a small slit in the cat’s skin. It was as if he were holding the handle of a zip. Again he pulled, and now there was a dark opening two inches long. William Cat’s purr was coming from in there.

The choice of Anthony Browne as illustrator is perfect. His detailed realistic images always have an element of the surreal in them, and McEwan’s writing embeds the mysterious in the quotidian detail of family life:

In the big untidy kitchen there was a drawer. Of course, there magmany drawers, but when someone said, ‘The string is in the kitchen drawer,’ everyone understood. The chances were the string would not be in the drawer. It was meant to be, along with a dozen other useful things that were never there: screwdrivers, scissors, sticky tape, drawing pins, pencils. If you wanted one of these, you looked in the drawer first, then you looked everywhere else. What was in the drawer was hard to define: things that had no natural place, things that had no use but did not deserve to be thrown away, things that might be mended one day. So—batteries that still had a little life, nuts without their bolts, the handle of a precious teapot, a padlock without a key or a combination lock whose secret number was a secret to everyone, the dullest kind of marbles, foreign coins, a torch without a bulb, a single glove from a pair lovingly knitted by Granny before she died, a hot water bottle stopper, a cracked fossil. By some magic reversal, everything spectacularly useless filed the drawer intended for practical tools. What could you do with a single piece of jigsaw? But, on the other hand, did you dare throw it away?

I think maybe this would be a good read-aloud book, to make the trickier ideas more accessible, and to be together for the weirder parts. The language is, as you’d expect, just right, good to hear.

I’m teaching Year 4 next year (8 and 9 year olds). So I’ve started to read books that they might like.

I’m teaching Year 4 next year (8 and 9 year olds). So I’ve started to read books that they might like.

I like Ian McEwan’s The Daydreamer a lot, though maybe it’s a bit too old for most Y4 children. Why too old? Perhaps the element of threat. But then again, maybe it’s OK…

It’s a book about a young boy who’s a daydreamer, dreaming about transformations.

My purpose is to tell of bodies which have been transformed into shapes of a different kind.

Ovid, Metamorphoses

So, in the wonderful chapter called The Cat, Peter discovers something unexpected about his cat:

Looking down through the fur, and parting it with the tips of his fingers ,he saw that he had opened up a small slit in the cat’s skin. It was as if he were holding the handle of a zip. Again he pulled, and now there was a dark opening two inches long. William Cat’s purr was coming from in there.

The choice of Anthony Browne as illustrator is perfect. His detailed realistic images always have an element of the surreal in them, and McEwan’s writing embeds the mysterious in the quotidian detail of family life:

In the big untidy kitchen there was a drawer. Of course, there were many drawers, but when someone said, ‘The string is in the kitchen drawer,’ everyone understood. The chances were the string would not be in the drawer. It was meant to be, along with a dozen other useful things that were never there: screwdrivers, scissors, sticky tape, drawing pins, pencils. If you wanted one of these, you looked in the drawer first, then you looked everywhere else. What was in the drawer was hard to define: things that had no natural place, things that had no use but did not deserve to be thrown away, things that might be mended one day. So—batteries that still had a little life, nuts without their bolts, the handle of a precious teapot, a padlock without a key or a combination lock whose secret number was a secret to everyone, the dullest kind of marbles, foreign coins, a torch without a bulb, a single glove from a pair lovingly knitted by Granny before she died, a hot water bottle stopper, a cracked fossil. By some magic reversal, everything spectacularly useless filed the drawer intended for practical tools. What could you do with a single piece of jigsaw? But, on the other hand, did you dare throw it away?

I think maybe this would be a good read-aloud book, to make the trickier ideas more accessible, and to be together for the weirder parts. The language is, as you’d expect, just right, good to hear.

It was thought-provoking when last week my excellent colleague Russel Tarr was accused by Secretary of State for Education Michael Gove of “infantilising” 14-year old students by asking them once they had finished studying the Weimar Republic, to re-present what they had learnt to younger 10-year old students in the form of their own Mr Men book.

It was thought-provoking when last week my excellent colleague Russel Tarr was accused by Secretary of State for Education Michael Gove of “infantilising” 14-year old students by asking them once they had finished studying the Weimar Republic, to re-present what they had learnt to younger 10-year old students in the form of their own Mr Men book.

Russel answered the criticism very sufficiently on his popular history site activehistory.co.uk – but I’ve been thinking about one aspect of the business, how and why we use fables.

Russel mentioned Orwell’s Animal Farm, but fables have a long history of being told to portray political events, though that’s may not be their only, or even main, purpose. The Kalilah and Dimnah fables of Persia for instance were in the frame story told by the sage Bidpai to a tyrant as a form of “mirror for princes”, a way to show things as they really were.

The oldest fable in the Bible is a political one, the fable of the Trees and the Brambles, given to discourage the people of Israel from adopting kingship:

One day the trees went out to anoint a king for themselves. They said to the olive tree, ‘Be our king.’ But the olive tree answered, ‘Should I give up my oil, by which both gods and humans are honored, to hold sway over the trees?’ Next, the trees said to the fig tree, ‘Come and be our king.’ But the fig tree replied, ‘Should I give up my fruit, so good and sweet, to hold sway over the trees?’ Then the trees said to the vine, ‘Come and be our king.’ But the vine answered, ‘Should I give up my wine, which cheers both gods and humans, to hold sway over the trees?’ Finally all the trees said to the thorn bush, ‘Come and be our king.’

One day the trees went out to anoint a king for themselves. They said to the olive tree, ‘Be our king.’ But the olive tree answered, ‘Should I give up my oil, by which both gods and humans are honored, to hold sway over the trees?’ Next, the trees said to the fig tree, ‘Come and be our king.’ But the fig tree replied, ‘Should I give up my fruit, so good and sweet, to hold sway over the trees?’ Then the trees said to the vine, ‘Come and be our king.’ But the vine answered, ‘Should I give up my wine, which cheers both gods and humans, to hold sway over the trees?’ Finally all the trees said to the thorn bush, ‘Come and be our king.’

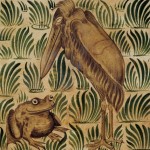

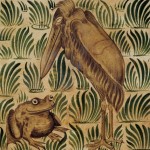

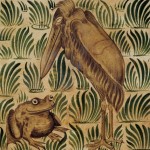

A similar Aesop’s fables is said to have been delivered by Aesop to the Athenians for a political purpose too, the Frogs who Desired a King:

The Frogs, grieved at having no established Ruler, sent ambassadors to Jupiter entreating for a King. Perceiving their simplicity, he cast down a huge log into the lake. The Frogs were terrified at the splash occasioned by its fall and hid themselves in the depths of the pool. But as soon as they realized that the huge log was motionless, they swam again to the top of the water, dismissed their fears, climbed up, and began squatting on it in contempt.

After some time they began to think themselves ill-treated in the appointment of so inert a Ruler, and sent a second deputation to Jupiter to pray that he would set over them another sovereign. He then gave them an Eel to govern them. When the Frogs discovered his easy good nature, they sent yet a third time to Jupiter to beg him to choose for them still another King. Jupiter, displeased with all their complaints, sent a Heron, who preyed upon the Frogs day by day till there were none left to croak upon the lake.

After some time they began to think themselves ill-treated in the appointment of so inert a Ruler, and sent a second deputation to Jupiter to pray that he would set over them another sovereign. He then gave them an Eel to govern them. When the Frogs discovered his easy good nature, they sent yet a third time to Jupiter to beg him to choose for them still another King. Jupiter, displeased with all their complaints, sent a Heron, who preyed upon the Frogs day by day till there were none left to croak upon the lake.

So, why tell a fable? Why not just recount the situation literally, as it “actually is”?

I’m not sure what the whole answer is, but part of it is the power of storytelling to magnetise listeners. Another part is that you can put the actual historical people aside for one moment, with all the positive and negative associations and responses you have to them, while you look at the basic structure of events. And a third thing is that the act of making or recognising the metaphor allows you to see the whole thing newly, freshly and memorably.

Whether the characters in the metaphor are bushes, or frogs or characters from a children’s story is not important – it’s that their relationships and actions to each other hold up a mirror to human affairs. To object that a signifier is a children’s book character is to mistake the container and the content. It would be like objecting to Newton’s f=ma because it uses mere letters of the alphabet to represent physical forces. It’s the truth of the metaphor that’s important.

Now all three reasons for using fables seem to me to be excellent reasons for getting children to use a metaphor of some kind from time to time to deepen and share their understanding of events.

Now all three reasons for using fables seem to me to be excellent reasons for getting children to use a metaphor of some kind from time to time to deepen and share their understanding of events.

It was thought-provoking when last week my excellent colleague Russel Tarr was accused by Secretary of State for Education Michael Gove of “infantilising” 14-year old students by asking them once they had finished studying the Weimar Republic, to re-present what they had learnt to younger 10-year old students in the form of their own Mr Men book.

It was thought-provoking when last week my excellent colleague Russel Tarr was accused by Secretary of State for Education Michael Gove of “infantilising” 14-year old students by asking them once they had finished studying the Weimar Republic, to re-present what they had learnt to younger 10-year old students in the form of their own Mr Men book.

Russel answered the criticism very sufficiently on his popular history site activehistory.co.uk – but I’ve been thinking about one aspect of the business in particular: how and why we use fables.

Russel mentioned Orwell’s Animal Farm, but fables have a long history of being told to portray political events, though that’s may not be their only, or even main, purpose. The Kalilah and Dimnah fables of Persia for instance were in the frame story told by the sage Bidpai to a tyrant as a form of “mirror for princes”, a way to show things as they really were.

The oldest fable in the Bible is a political one, the fable of the Trees and the Brambles, given to discourage the people of Israel from adopting kingship:

One day the trees went out to anoint a king for themselves. They said to the olive tree, ‘Be our king.’ But the olive tree answered, ‘Should I give up my oil, by which both gods and humans are honored, to hold sway over the trees?’ Next, the trees said to the fig tree, ‘Come and be our king.’ But the fig tree replied, ‘Should I give up my fruit, so good and sweet, to hold sway over the trees?’ Then the trees said to the vine, ‘Come and be our king.’ But the vine answered, ‘Should I give up my wine, which cheers both gods and humans, to hold sway over the trees?’ Finally all the trees said to the thorn bush, ‘Come and be our king.’ The thorn bush said to the trees, `If you really want to anoint me king over you, come and take refuge in my shade; but if not, then let fire come out of the thorn bush and consume the cedars of Lebanon!’

One day the trees went out to anoint a king for themselves. They said to the olive tree, ‘Be our king.’ But the olive tree answered, ‘Should I give up my oil, by which both gods and humans are honored, to hold sway over the trees?’ Next, the trees said to the fig tree, ‘Come and be our king.’ But the fig tree replied, ‘Should I give up my fruit, so good and sweet, to hold sway over the trees?’ Then the trees said to the vine, ‘Come and be our king.’ But the vine answered, ‘Should I give up my wine, which cheers both gods and humans, to hold sway over the trees?’ Finally all the trees said to the thorn bush, ‘Come and be our king.’ The thorn bush said to the trees, `If you really want to anoint me king over you, come and take refuge in my shade; but if not, then let fire come out of the thorn bush and consume the cedars of Lebanon!’

A similar Aesop’s fables is said to have been delivered by Aesop to the Athenians for a political purpose too, the Frogs who Desired a King:

The Frogs, grieved at having no established Ruler, sent ambassadors to Jupiter entreating for a King. Perceiving their simplicity, he cast down a huge log into the lake. The Frogs were terrified at the splash occasioned by its fall and hid themselves in the depths of the pool. But as soon as they realized that the huge log was motionless, they swam again to the top of the water, dismissed their fears, climbed up, and began squatting on it in contempt.

After some time they began to think themselves ill-treated in the appointment of so inert a Ruler, and sent a second deputation to Jupiter to pray that he would set over them another sovereign. He then gave them an Eel to govern them. When the Frogs discovered his easy good nature, they sent yet a third time to Jupiter to beg him to choose for them still another King. Jupiter, displeased with all their complaints, sent a Heron, who preyed upon the Frogs day by day till there were none left to croak upon the lake.

After some time they began to think themselves ill-treated in the appointment of so inert a Ruler, and sent a second deputation to Jupiter to pray that he would set over them another sovereign. He then gave them an Eel to govern them. When the Frogs discovered his easy good nature, they sent yet a third time to Jupiter to beg him to choose for them still another King. Jupiter, displeased with all their complaints, sent a Heron, who preyed upon the Frogs day by day till there were none left to croak upon the lake.

So, why construct a fable? Why not just recount the situation literally, as it “actually is”?

I’m not sure what the whole answer is, but part of it is the power of storytelling to magnetise listeners. Another part is that you can put the actual historical people aside for one moment, with all the positive and negative associations and responses you have to them, while you look at the basic structure of events. And a third thing is that the act of making or recognising the metaphor allows you to see the whole thing newly, freshly and memorably.

Whether the characters in the metaphor are bushes, or frogs or characters from a children’s story is not important – it’s that their relationships and actions to each other hold up a mirror to human affairs. To object that a signifier is a children’s book character is to mistake the container and the content. It would be like objecting to Newton’s f=ma because it uses mere letters of the alphabet to represent physical forces. It’s the truth of the metaphor that’s important.

Now all three reasons for using fables seem to me to be excellent reasons for getting children to use a metaphor of some kind from time to time to deepen and share their understanding of events.

Now all three reasons for using fables seem to me to be excellent reasons for getting children to use a metaphor of some kind from time to time to deepen and share their understanding of events.

I’ve just come across Carin Berger’s All Mixed Up. It’s one of those mix-and-match flip books where you can mix and match body parts from different people to create lots of new people. You can actually virtually turn the pages here.

I’ve just come across Carin Berger’s All Mixed Up. It’s one of those mix-and-match flip books where you can mix and match body parts from different people to create lots of new people. You can actually virtually turn the pages here.

I’ve been reading Odysseus to my class over the last few months, and as part of the work we did, we created some mythical beasts. At first I had the idea that it would be a mix and match book. Then I wanted them all to have collaborated in creating one combined beast. Anyway, I liked what they created and wrote so much I didn’t have any flipping or flapping. Here’s the book.

[ gigya src="http://static.issuu.com/webembed/viewers/style1/v1/IssuuViewer.swf" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" allowfullscreen="true" menu="false" style="width:420px;height:297px" flashvars="mode=embed&layout=http%3A%2F%2Fskin.issuu.com%2Fv%2Flight%2Flayout.xml&showFlipBtn=true&documentId=130125154236-8b52144e9a9f4e92a7f651aabbcddced&docName=mythical_creatures&username=simongregg&loadingInfoText=Mythical%20Creatures&et=1362341274782&er=79" ]

One of the flip books that I’ve got and like a lot is Tony Meeuwissen’s Remarkable Animals – 1000 Amazing Amalgamations.

Each creature has a head, a body and a tail, and you can mix them up and read the descriptions.

I’ve just come across Carin Berger’s All Mixed Up. It’s one of those mix-and-match flip books where you can mix and match body parts from different people to create lots of new people. You can actually virtually turn the pages here.

I’ve just come across Carin Berger’s All Mixed Up. It’s one of those mix-and-match flip books where you can mix and match body parts from different people to create lots of new people. You can actually virtually turn the pages here.

I’ve been reading Odysseus to my class over the last few months, and as part of the work we did, we created some mythical beasts. At first I had the idea that it would be a mix and match book. Then I wanted them all to have collaborated in creating one combined beast. Anyway, I liked what they created and wrote so much I didn’t have any flipping or flapping. Here’s the book.

One of the flip books that I’ve got and like a lot is Tony Meeuwissen’s Remarkable Animals – 1000 Amazing Amalgamations.

Each creature has a head, a body and a tail, and you can mix them up and read the descriptions.

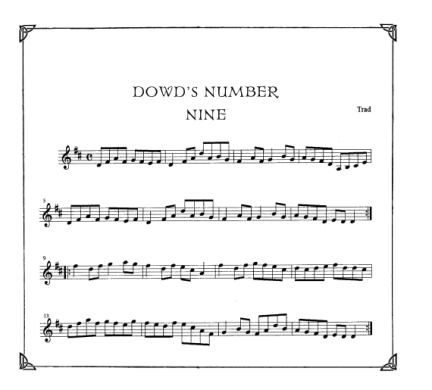

Kate Thompson‘s The New Policeman is adorned not with pictures but with music.

Music runs through the tale, and you can hear some of the jigs and reels on Kate Thompson’s website.

The story, though written with an eye and ear for the detail of life in Kinvara, is a fantasy. Fifteen year-old JJ has to go a lot further from, and a lot closer to, home than he expects to find the time that everyone is so short of.

Kate Thompson‘s The New Policeman is adorned not with pictures but with music.

Music runs through the tale, and you can hear some of the jigs and reels on Kate Thompson’s website.

The story, though written with an eye and ear for the detail of life in Kinvara, is a fantasy. Fifteen year-old JJ has to go a lot further from, and a lot closer to, home than he expects to find the time that everyone is so short of.

By:

simonsterg,

on 12/26/2012

Blog:

Yahoo! 360

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Tales,

SF Said,

children,

Illustration,

storytelling,

book,

Dave McKean,

stories,

cat,

Add a tag

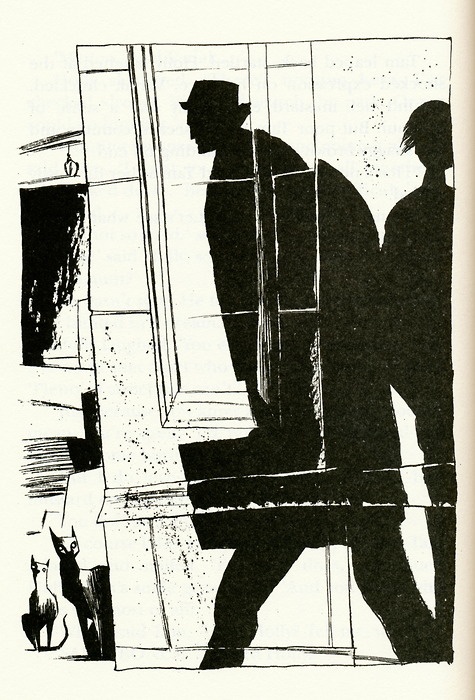

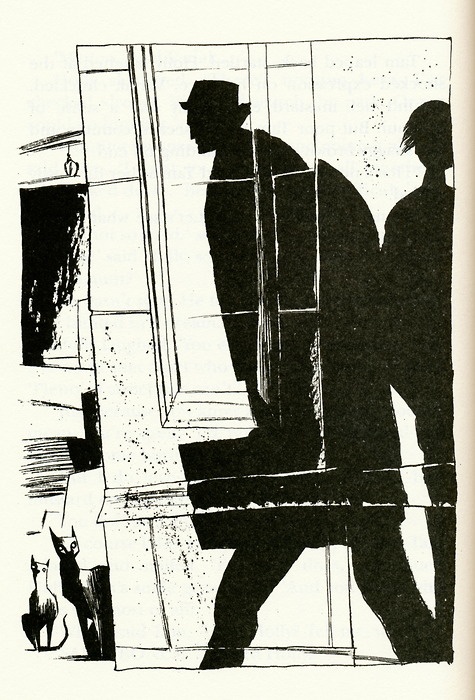

“There are Seven Skills in the Way of Jalal,” whispered the Elder Paw. ”We know only three of them. Their names are these. Slow-Time. Moving Circles. Shadow-Walking.”

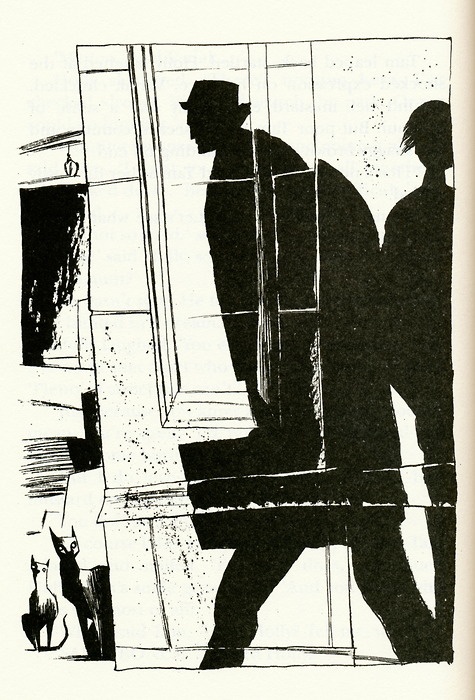

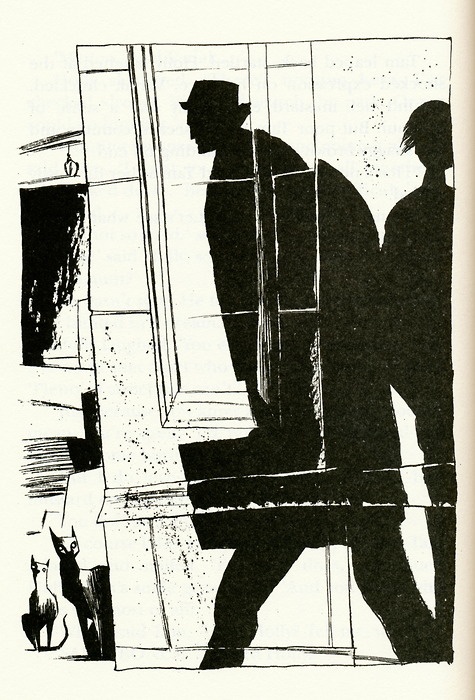

SF Said‘s Varjak Paw is a tale of a pet cat who must grow up, learn to survive Outside, and learn the Seven Skills of his ancestor Jalal. He uses the skills, which he learns from Jalal in his dreams, to help his new street cat friends, Holly and Tam.

As usual David McKean’s illustrations are amazing, and complement the text brilliantly.

“There are Seven Skills in the Way of Jalal,” whispered the Elder Paw. ”We know only three of them. Their names are these. Slow-Time. Moving Circles. Shadow-Walking.”

SF Said‘s Varjak Paw is a tale of a pet cat who must grow up, learn to survive Outside, and learn the Seven Skills of his ancestor Jalal. He uses the skills, which he learns from Jalal in his dreams, to help his new street cat friends, Holly and Tam.

As usual David McKean’s illustrations are amazing, and complement the text brilliantly.

The frogge vppon a tyme whan she sawe the crabbe swymmynge by the watersyde spake and sayde: “What is he, this so fowle and vncomly, that is so bold to trouble my watyr? Forsomoch as I am mighty and stronge both in watyr and lond I shal go and dryue him away.”

The frogge vppon a tyme whan she sawe the crabbe swymmynge by the watersyde spake and sayde: “What is he, this so fowle and vncomly, that is so bold to trouble my watyr? Forsomoch as I am mighty and stronge both in watyr and lond I shal go and dryue him away.”

And aftir this saying she made a lepe as though she wold haue oppressyd the crabbe and sayde: “O thow wretche, why art not thow shamefaste to entyr in to my restynge place? Arte not thowe confusyd to defyle the watyr that is so fayre and bright whan thow arte so fowle soo blacke and soo odyows?”

The crabbe as he is vsyd to do went euyr bakwarde, saynge to the frogge, “Syster, saye not soo, for I desyre to haue thy loue and to be at peace withe the. Therfore I praye the entyr not vppon me withe vyolence.”

And the frogge, seynge hym goynge baltwarde beleuid that he had doone soo for fere of her.

Wherfore she began to greue him more and more both with woordes and dedys, saynge: “Withdrawe not thy self, thowe moost fowle, for thow mayst not escape, for this same daye I shall fede fysshes with the.”

And euyn forthwith that same woorde she made a lepe wyllynge to sle the crabbe. The crabbe, seynge the greate iubardye and that he cowde not escape, he tournyd him self and disposyd him to batell and caught the frogge with his cleys and bote her and plukkyd her to smale pecys and sayde:

“He that to batell is compellyd to goo

Let him fight manly with his mortall foo.”

-o-

Another story from the first English version of the Dialogus Creaturarum. The picture is again from Claude Nourry’s 1509 edition printed at Lyon.

The frogge vppon a tyme whan she sawe the crabbe swymmynge by the watersyde spake and sayde: “What is he, this so fowle and vncomly, that is so bold to trouble my watyr? Forsomoch as I am mighty and stronge both in watyr and lond I shal go and dryue him away.”

The frogge vppon a tyme whan she sawe the crabbe swymmynge by the watersyde spake and sayde: “What is he, this so fowle and vncomly, that is so bold to trouble my watyr? Forsomoch as I am mighty and stronge both in watyr and lond I shal go and dryue him away.”

And aftir this saying she made a lepe as though she wold haue oppressyd the crabbe and sayde: “O thow wretche, why art not thow shamefaste to entyr in to my restynge place? Arte not thowe confusyd to defyle the watyr that is so fayre and bright whan thow arte so fowle soo blacke and soo odyows?”

The crabbe as he is vsyd to do went euyr bakwarde, saynge to the frogge, “Syster, saye not soo, for I desyre to haue thy loue and to be at peace withe the. Therfore I praye the entyr not vppon me withe vyolence.”

And the frogge, seynge hym goynge baltwarde beleuid that he had doone soo for fere of her.

Wherfore she began to greue him more and more both with woordes and dedys, saynge: “Withdrawe not thy self, thowe moost fowle, for thow mayst not escape, for this same daye I shall fede fysshes with the.”

And euyn forthwith that same woorde she made a lepe wyllynge to sle the crabbe. The crabbe, seynge the greate iubardye and that he cowde not escape, he tournyd him self and disposyd him to batell and caught the frogge with his cleys and bote her and plukkyd her to smale pecys and sayde:

“He that to batell is compellyd to goo

Let him fight manly with his mortall foo.”

-o-

Another story from the first English version of the Dialogus Creaturarum. The picture is again from Claude Nourry’s 1509 edition printed at Lyon.

It happyd in a greate solempne feste, Fisshes of the floode walkyd togidre after Dynar in great tranquillyte and peace for to take ther recreacyon and solace; but the Carpe began to trowble the feste, erectynge hym self by pryde & saynge, I am worthy to be lawdyd aboue all othir, for my flesshe is delicate and swete more than it can be tolde of. I haue not be nourished nothir in dychesse, nor stondyngh watyrs, nor pondes; but I haue be brought vppe in the floode of the greate garde. Wherfore I owe to be Prynce and Regent amonge all yowe.

It happyd in a greate solempne feste, Fisshes of the floode walkyd togidre after Dynar in great tranquillyte and peace for to take ther recreacyon and solace; but the Carpe began to trowble the feste, erectynge hym self by pryde & saynge, I am worthy to be lawdyd aboue all othir, for my flesshe is delicate and swete more than it can be tolde of. I haue not be nourished nothir in dychesse, nor stondyngh watyrs, nor pondes; but I haue be brought vppe in the floode of the greate garde. Wherfore I owe to be Prynce and Regent amonge all yowe.

Ther is a Fissh callyd Tymal’ lus, hauinge his name a Flowre, for Tinius is callyd a Flowre; and this Tymallus is a Fissh of the See, as saithIsidore, Ethimologiarum, xii. and allthoughe that he be fauoureable in sight and delectable in taste, yet moreouir the Fyssh of hym smellyth swete lyke a flowre and geuith a pleasaunte odour. And so this Fyssh Tymallus, hering this saynge of the Carpe, had greate scorne of him and sterte forth & sayde: It is not as thou sayste, for I shine more bright than thowe, and excede the in odowre and relece. Who may be comparyd rnto me, for he that fyndith me hath a great Tresowre. If thow haue thy dwellynge oonly in the watir of garde, I haue myn abydynge in many large floodes.

And so emong them were great stryuis and contencyons. Wherfore the feste was tournyd in to great trowble, for some fauowryd the parte of the one and some of the othir, so that be lyklyhode there shukl haue growen greate myschefe emonge them: for eueiy of them began to snak at othir, & wulde haue torne eche other on smale pecys.

Ther was monge all othir a Fissh callyd Truta euyr mouyd to breke stryfe;and soo thys Trowte for asmoche as she was agjd, and wele lernyd, she spake and sayde: Brediyn, it is not good to stryue & fight for vayne lawdatowris and praysers; for I prayse not my self though some personis thinke me worthy to be commendid; for it is wryttyn, the Mowth of an othir Man mote commende the and not thyn owne, for all commendacyon and lawde of hym self is fowle in y*. mouth of the Spekar. Therefore bettyr hit is that those that prayse them self goo togider to the see luge, that is, the Dolphyn, which is a iust luge and a rightfull and dredinge God, for he shall rightfully determyn this mater.

This Counsell plesyd them well, and forth went these twayn togider vnto the Dolphyn. and shewyd to him all ther myndes, and to ther power comendid the self. To whom the Dolphyn sayde: Children, I neuyr sawe yowe tell this tyme, for ye be alwaye hydde in the floodes, and 1 am steringe iu the great Wawys of the See; wherfore I cannot gyue ryghtfull Sentence betwene yowe, but yf I first assaye and make a Taste of yowe. And thus saynge, he gaue a sprynge and swalowyd them in both two, and sayde,

Noman owith hym self to commende,

Aboue all other, laste he offende.

-o-

This fable of the Dolphin and the Fish is from a medieval collection called the Creature Conversations, or in Latin Dialogus Creaturarum. It’s very like the story told here before of the Two Otters and Jackal. Even though it makes hard reading – can you read it? – I’ve left the English as it was five hundred years ago.

It happyd in a greate solempne feste, Fisshes of the floode walkyd togidre after Dynar in great tranquillyte and peace for to take ther recreacyon and solace; but the Carpe began to trowble the feste, erectynge hym self by pryde & saynge, I am worthy to be lawdyd aboue all othir, for my flesshe is delicate and swete more than it can be tolde of. I haue not be nourished nothir in dychesse, nor stondyngh watyrs, nor pondes; but I haue be brought vppe in the floode of the greate garde. Wherfore I owe to be Prynce and Regent amonge all yowe.

It happyd in a greate solempne feste, Fisshes of the floode walkyd togidre after Dynar in great tranquillyte and peace for to take ther recreacyon and solace; but the Carpe began to trowble the feste, erectynge hym self by pryde & saynge, I am worthy to be lawdyd aboue all othir, for my flesshe is delicate and swete more than it can be tolde of. I haue not be nourished nothir in dychesse, nor stondyngh watyrs, nor pondes; but I haue be brought vppe in the floode of the greate garde. Wherfore I owe to be Prynce and Regent amonge all yowe.

Ther is a Fissh callyd Tymal’ lus, hauinge his name a Flowre, for Tinius is callyd a Flowre; and this Tymallus is a Fissh of the See, as saithIsidore, Ethimologiarum, xii. and allthoughe that he be fauoureable in sight and delectable in taste, yet moreouir the Fyssh of hym smellyth swete lyke a flowre and geuith a pleasaunte odour. And so this Fyssh Tymallus, hering this saynge of the Carpe, had greate scorne of him and sterte forth & sayde: It is not as thou sayste, for I shine more bright than thowe, and excede the in odowre and relece. Who may be comparyd rnto me, for he that fyndith me hath a great Tresowre. If thow haue thy dwellynge oonly in the watir of garde, I haue myn abydynge in many large floodes.

And so emong them were great stryuis and contencyons. Wherfore the feste was tournyd in to great trowble, for some fauowryd the parte of the one and some of the othir, so that be lyklyhode there shukl haue growen greate myschefe emonge them: for eueiy of them began to snak at othir, & wulde haue torne eche other on smale pecys.

Ther was monge all othir a Fissh callyd Truta euyr mouyd to breke stryfe;and soo thys Trowte for asmoche as she was agjd, and wele lernyd, she spake and sayde: Brediyn, it is not good to stryue & fight for vayne lawdatowris and praysers; for I prayse not my self though some personis thinke me worthy to be commendid; for it is wryttyn, the Mowth of an othir Man mote commende the and not thyn owne, for all commendacyon and lawde of hym self is fowle in y*. mouth of the Spekar. Therefore bettyr hit is that those that prayse them self goo togider to the see luge, that is, the Dolphyn, which is a iust luge and a rightfull and dredinge God, for he shall rightfully determyn this mater.

This Counsell plesyd them well, and forth went these twayn togider vnto the Dolphyn. and shewyd to him all ther myndes, and to ther power comendid the self. To whom the Dolphyn sayde: Children, I neuyr sawe yowe tell this tyme, for ye be alwaye hydde in the floodes, and 1 am steringe iu the great Wawys of the See; wherfore I cannot gyue ryghtfull Sentence betwene yowe, but yf I first assaye and make a Taste of yowe. And thus saynge, he gaue a sprynge and swalowyd them in both two, and sayde,

Noman owith hym self to commende,

Aboue all other, laste he offende.

-o-

This fable of the Dolphin and the Fish is from a medieval collection called the Creature Conversations, or in Latin Dialogus Creaturarum. It’s very like the story told here before of the Two Otters and Jackal. Even though it makes hard reading – can you read it? – I’ve left the English as it was five hundred years ago.

Thanks Mick for the Story Cubes.

Already they’ve been generating all sorts of fantastical fictions.

Not only that, but I obviously think, “How would that work with children?” I’m going to try it out.

And then I think, “What if the pictures were different?” and “What pictures would I put on the dice, that would lead to the most interesting and various places?”

There’s heavy cloud sweeping over Skye, so already they’ve been in use today.

Then again, maybe a more complicated story generator is needed.

I saw, via the Internet, at the Story Museum in Oxford they had reconstructed a nineteenth century Storyloom.

The machine is more precisely known as Rochester’s Extraordinary Storyloom. This page tells us that “Victorian inventor Barnabas Rochester had an interest in stories but little talent for writing them – which is why he is said to have built the Storyloom.”

It’s Ted Dewan who is the engineer behind the reconstruction of the storyloom. His website is wormworks.com

Ted Dewan is an amazing illustrator when he’s not doing reconstructive engineering. I especially like his black and white pictures for Robert Ornstein’s books:

Thanks Mick for the Story Cubes.

Already they’ve been generating all sorts of fantastical fictions.

Not only that, but I obviously think, “How would that work with children?” I’m going to try it out.

And then I think, “What if the pictures were different?” and “What pictures would I put on the dice, that would lead to the most interesting and various places?”

There’s heavy cloud sweeping over Skye, so already they’ve been in use today.

Then again, maybe a more complicated story generator is needed.

I saw, via the Internet, at the Story Museum in Oxford they had reconstructed a nineteenth century Storyloom.

The machine is more precisely known as Rochester’s Extraordinary Storyloom. This page tells us that “Victorian inventor Barnabas Rochester had an interest in stories but little talent for writing them – which is why he is said to have built the Storyloom.”

It’s Ted Dewan who is the engineer behind the reconstruction of the storyloom. His website is wormworks.com

Ted Dewan is an amazing illustrator when he’s not doing reconstructive engineering. I especially like his black and white pictures for Robert Ornstein’s books:

The Mouse and His Child – wonderful book! – is now a play!

-

And to make it complete, there’s a clockwork installation from the MAD museum.

By:

simonsterg,

on 10/25/2012

Blog:

Yahoo! 360

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Illustration,

storytelling,

book,

Shaun Tan,

stories,

rabbit,

Tales,

wisdom,

fable,

Add a tag

Just read the amazing Rabbits written by John Marsden and illustrated by Shaun Tan. The pictures taken from the book here are from

Shaun Tan’s website.In the story the rabbits come, they take over, they build, they remove, they subjugate. Shaun Tan documents the tragedy of their conquest in beautiful detail:

-

-

-

-

By:

simonsterg,

on 10/24/2012

Blog:

Yahoo! 360

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

children,

Illustration,

storytelling,

book,

stories,

Tales,

wisdom,

Nasrudin,

Laurence Fugier,

Véronique Joffre,

Add a tag

I’ve just sat outside on this warm autumn evening and read La Folle Journée de Nasreddin Hodja, a picture-book by Laurence Fugier, wonderfully illustrated by Véronique Joffre.

Some stories I didn’t know too! Here’s Nasreddin when he learns that small song birds are sold for three pieces of silver, selling his turkey – which after all is much bigger – for ten pieces of gold:

Here he is pouring hot water from the baths into the stream, because his donkey likes his herbs in tea form:

And here he is – this one’s familiar – “keeping an eye on the door” in case of burglars – by carrying it around with him:

Véronique Joffre’s simple collage-style illustrations in cool colours suit the spareness of the tales perfectly!

By:

simonsterg,

on 10/13/2012

Blog:

Yahoo! 360

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Stephen Wildish,

children,

Illustration,

book,

film,

stories,

Tales,

Allan Ahlberg,

Janet Ahlberg,

Add a tag

Seeing this diagram by Stephen Wildish, reminded me of the very satisfying formula at the beginning of Allan Ahlberg‘s Funnybones:

Allan and Janet Ahlberg produced so many fantastic picture books, and often what made them so good was the simplicity of the idea.

The opening lines of this one:

In a dark, dark town there was a dark, dark street

and in the dark, dark street there was a dark, dark house,

and in the dark, dark house there were some dark, dark stairs

and down the dark, dark stairs there was a dark, dark cellar

and in the dark dark cellar….

Three skeletons lived!

The pictures work brilliantly too, with the black background throughout. The book worked so well that the Ahlbergs made lots of follow-ups.

The cartoonified version stuck fairly faithfully to it, though there’s not a really good quality version on YouTube. Griff Rhys Jones was the ideal narrator:

Just finished Patrick Ness and Jim Kay’s A Monster Calls. What a tale! So good that when Matthew came round , I straight away got him reading it! He’s taken it away with him now.

Picture from the book, The Guardian

The circumstances of the book’s making are interesting in themselves. As Patrick Ness says in The Guardian:

My editor, Denise Johnstone-Burt, had commissioned a book from Siobhan Dowd, based on a idea Siobhan had talked with her about. I’ve seen emails from Siobhan talking about how she couldn’t wait to get properly started on the notes and early prose she’d written. But very sadly, she died from breast cancer before she could finish it. Denise didn’t want the idea to disappear, though. I wasn’t perhaps the most obvious choice at the time, considering that Siobhan’s books tended towards the realistic and mine tended to the fantastical, but what I hope we have in common is a kind of wanting the emotional truth for our readers, of wanting teenagers to be taken seriously, as complex beings. And that can be true no matter where your story is set.

It is a tale of a boy, Conor, with a mother who is fighting a long battle against life-threatening illness. The monster that calls is in the form of the yew tree from the graveyard, but a yew tree that walks and talks. It tells Conor that it has three stories, and that it will want Conor’s story, the truth, his truth afterwards. There are things Conor doesn’t want to tell. There are the nightmares that he always has. But the tree drags it out of him, makes him tell the truth he didn’t tell even to himself, makes him realise the lie that went with it.

0 Comments on Reading A Monster Calls as of 1/1/1900

0 Comments on Reading A Monster Calls as of 1/1/1900

After some time they began to think themselves ill-treated in the appointment of so inert a Ruler, and sent a second deputation to Jupiter to pray that he would set over them another sovereign. He then gave them an Eel to govern them. When the Frogs discovered his easy good nature, they sent yet a third time to Jupiter to beg him to choose for them still another King. Jupiter, displeased with all their complaints, sent a Heron, who preyed upon the Frogs day by day till there were none left to croak upon the lake.

After some time they began to think themselves ill-treated in the appointment of so inert a Ruler, and sent a second deputation to Jupiter to pray that he would set over them another sovereign. He then gave them an Eel to govern them. When the Frogs discovered his easy good nature, they sent yet a third time to Jupiter to beg him to choose for them still another King. Jupiter, displeased with all their complaints, sent a Heron, who preyed upon the Frogs day by day till there were none left to croak upon the lake. Now all three reasons for using fables seem to me to be excellent reasons for getting children to use a metaphor of some kind from time to time to deepen and share their understanding of events.

Now all three reasons for using fables seem to me to be excellent reasons for getting children to use a metaphor of some kind from time to time to deepen and share their understanding of events.

After some time they began to think themselves ill-treated in the appointment of so inert a Ruler, and sent a second deputation to Jupiter to pray that he would set over them another sovereign. He then gave them an Eel to govern them. When the Frogs discovered his easy good nature, they sent yet a third time to Jupiter to beg him to choose for them still another King. Jupiter, displeased with all their complaints, sent a Heron, who preyed upon the Frogs day by day till there were none left to croak upon the lake.

After some time they began to think themselves ill-treated in the appointment of so inert a Ruler, and sent a second deputation to Jupiter to pray that he would set over them another sovereign. He then gave them an Eel to govern them. When the Frogs discovered his easy good nature, they sent yet a third time to Jupiter to beg him to choose for them still another King. Jupiter, displeased with all their complaints, sent a Heron, who preyed upon the Frogs day by day till there were none left to croak upon the lake. Now all three reasons for using fables seem to me to be excellent reasons for getting children to use a metaphor of some kind from time to time to deepen and share their understanding of events.

Now all three reasons for using fables seem to me to be excellent reasons for getting children to use a metaphor of some kind from time to time to deepen and share their understanding of events.

I loved the description of that drawer!

Yes, I thought it was only us that had drawers like that!