Naturally the UCW has been all agog over WIFYR. And sadly, I was not able to attend this year (sigh). But it got me thinking about all of the inspiration I've received from writing groups and conferences over the years. One speech given last year at WIFYR by Stephen Fraser, a literary agent from Jennifer De Chiara Lit Agency, has really stuck with me.

What he essentially talked about was the importance of following your inner compass.

At many conferences and at many writing classes, the fear for most not-yet-published writers is to look like an unpublished writer. To look like an amateur. So a zillion classes are given about what the "rules" of publishing are: exactly how long each genre should be, exactly how it should be written, exactly what most publishers are looking for ....

I don't know about you, but I always bristle at these boxes and labels and rules. My hand is the one that shoots up every time with the every annoying "But why?" (Yep, I'm still that kid in class.) Why do books with beautiful illustrations have to be for three-year-olds? Why do characters in middle grade books have to use pop-culture vernacular? Why can't a picture book have 1500 words? Why ...? Why ...? Why ...?

There are many reasons to follow many of the rules. But the answer usually given to me is always the least satisfying: Because publishers know that X sells because that is what has sold.

But Fraser pointed out the importance of being the first. You never know if your version of breaking the rules could be the one that starts a new trend.

Who knew sparkly vampires would be irresistible until it was done? Who thought that mixing fairy tale archetypes into a hodgepodge world based on Greek mythology and Joseph Campbell-like folklore would capture the fascination of young readers in today's pop culture ... until it was done? Who knew that rewriting classics using monsters would be a "thing"? Who said Death could be a popular narrator?

And this viewpoint came from a well-known literary agent who had previously worked at such publishing houses as HarperCollins, Scholastic, and Simon & Schuster. In other words, a guy who is looking to publish rule-breakers. There are those in the publishing industry that can think outside of the highly organized, very rigid box of publishing.

And they are looking for writers like you and me.

This fact has probably given me more strength and determination to keep writing than any I've received.

So break it. The rule. The narrative arc. The law. The genre. The stylebook. The mold. The norm.

Take that idea of yours that just doesn't fit and run with it.

Write it from your soul. Be the one to do what hasn't yet been done.

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: writing rules, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 16 of 16

Blog: Utah Children's Writers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: creative writing, writing rules, Stephen Fraser, WiFYR, break the mold, inner compass, Add a tag

Blog: Guide to Literary Agents (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Uncategorized, freelancing, writing rules, freelance, writing goals, no rules, Better Writing, There Are No Rules Blog by the Editors of Writer's Digest, Tips & Advice, Add a tag

BY ???

–

You don’t know my name. You don’t know my face. But it’s now several decades since I earned my first farthings by putting words in some sort of publishable order … at last tabulation, now some 3,000,000 in print, and still counting. I’ve produced novels, nonfiction books, fiction stories, nonfiction articles, photo features, screenplays, multi-media scripts and even catalogs and speeches. Call it meat-and-potato writing. One of my catch phrases is, “If you can point at it, I can write it,” which relates to an eclectic approach to both subject matter and genre. Writers, like the human species, profit best as omnivores.

So I’ve decided to spill the beans as it were. It’s time to come out of the freelance writer’s closet and perhaps pass on some pearls, cultured or otherwise, concerning the lessons I’ve learned—some I’ve purloined, some spurned, but now ready to return to those standing at that proverbial fork in the writer’s road. To be a writer or not to be, or more importantly, whether one can earn a living in its pursuit. Maintaining that metaphor, my Uncle Duncan from Gallway would often wag his finger in front of our young upturned faces and admonish us with these words of wisdom: “When you come to that fork in the road, take the spoon!” We had no idea what he was talking about, but he would laugh himself silly.

Now let me step back in time to that indelible image when my first words appeared in print. It was a check for $10. Oh, the beckoning lure of lucre ignites the Muses’ fury. Seen through the wide eyes of a 10-year-old back in the mid-1950s, it was a momentous amount. The prize money resulted from my entry in an elementary school campaign focusing on the dangers of smoking. I had drawn a scary-looking cigarette and penned a few words curling out of its burning wrinkle of a mouth. It was a winner and the check was awarded to me in front of my fellow schoolmates. My face burned red and my hands shook as I held the check and certificate. From that day I never stopped writing nor did I ever take a puff.

Now to those promised Ten Lessons learned along with some self-indulgent biography to provide credence to my pronouncements on successful freelance writing. To get things started…

Lesson One: Freelance does not mean you work for free … although a lot of current Internet sites seem to think so. They offer “exposure” which reminds me of being left out in the freezing cold. True, we all know one must create a “buzz” or “go viral” to get any attention these days, so maybe passing out some free samples might be a good idea. Or as Lenny Bruce said, “Time to grow up and sell out.” Other options include entering any of the myriad “writing competitions” most of which now seem to charge an entry fee, another money maker for the legions of struggling publications which we naturally hope remain with us. Today, in response to the “screen culture” many jump into the whirl of words with their own blog, some even capturing considerable audiences that can attract “sponsors” and thus some payment in return. Of course, for those that have the back-up of a “real world” job can practice their writing on the side while adhering to oft heard aspiring writer’s mantra… “keep your day job.” Bottom line, living the life as a full-time writer, and like getting old, is not for sissies.

Lesson Two (in the form of a question): What is the difference between an amateur writer and a professional writer? Answer: The only difference is that the professional gets paid.

Ok, now back to my credentials. Fast forward a few more years into the early 1960s and a south Florida high school where I was elected president of the Creative Writing Club. Our group was one rung up the geek ladder from the A-V Club but we benefited from a great mentor, our English teacher, Mrs. Young, who fanned our teen-aged angst into poems, essays and fiction appearing in our school publication aptly named The Raconteur. I tried my hand at all the various genres to varying degrees of success. I also penned an “expose” of the clique-culture of my high school contemporaries that so impressed my psychology teacher that copies were printed up and disseminated throughout the school which resulted in the other teachers looking at me warily as some kind of wunderkind/freak while my schoolmates were further convinced of my geekhood but now one deserving of total banishment from their society. It was my first work of journalism, but certainly not my last. Undaunted by a lack of comparison with Milton, Salinger or Walter Cronkite, I pressed on.

There followed a bit of a hiatus, beyond term papers, while attending Tulane University where my major in psychology shifted to the path of least resistance to homework…English…aided by a predilection to intense studies of Smirnoff 101. Hey, after all this was New Orleans and the distractions were of Mardi Gras-proportions. One could chalk us this period to what writers traditionally call their “experience-gathering time.” If you haven’t lived it, how you can write it? At least that was my excuse.

Upon a miraculous graduation, a year followed teaching “Communication Techniques” to children dealing with life within a migrant agricultural worker environment. This is a whole other story, but suffice it to say it further tempered my life as a writer. My students delved into performing plays and writing haiku of such quality that the state authorities displayed their work. It was a learning experience all around and my first foray into helping others find their writer’s “voice” and in turn my own. It was yet another fork in the writer’s road, and like Rome, it all led to the same destination.

After the teaching stint, I ingratiated myself into the venerable Johns Hopkins Writing Seminars, an M.A. program. Blissful is the word that comes to mind. It was all about writing with other committed writers and outstanding instructors. During this stay in Baltimore, with a statue of Edgar Allan Poe lurking outside my apartment doorway, I published my first “official” story. As it turned out, the short story took First Place in the Carolina Quarterly’s Young Fiction Writers national competition. It certainly helped with my course grade as well as other “perks” as a Young Turk now with something of a writer’s credit.

Somewhat “authenticated” by the success and after graduation I sat down for six weeks at a small Olivetti typewriter and with nothing else to do “between jobs” I wrote a science fiction novel. I sent it “cold” to Bantam Books who then passed it on to Doubleday who published it, no doubt based on the gracious preliminary review given by A.E. Van Vogt, one of the icons of the sci-fi world at the time. Publication really never went to my head … it only meant it was time to write something else.

I then decided to try my hand in Hollywood and so made the move from Florida to L.A. where I planned to get rich and famous. It’s good to have a goal. It’s also good to have a sandwich to eat now and then. After several weeks guarding outdoor furniture in a shopping mall all night long, I sought a job as a janitor at USC, but somehow found myself taking and teaching classes. (It was either that or a scheduled appearance as a contestant on the Tic-Tac-Dough TV game show…yet another story.) Okay, so now I was teaching freshmen the art form of composition, basically essay writing. Teaching forces one to convey strategies of writing in a comprehensible form, in this case to18-year olds who for the most part couldn’t write their way out of a wet paperback book. The concepts of inductive and deductive reasoning were not in their repertoire of skill sets. It was enough trouble to get them to write with a pen instead of a pencil. But there was progress. One, I was able to convince them that while writing was an unnatural process, far from the brain centers for normal speech, it could be approached by a simple paradigm, a set of rules to follow to create a palatable essay, their goal for the class. And two, yes, you do have something worth writing about, perhaps the greatest initial obstacle to overcome. For the following two years my graduate work in media and literature co-existed with my teaching duties, and there occasionally appeared a glimmer of hope. While most of the students seemed more concerned about the ski slope conditions for the weekend, every now and a nascent writer recognized his or herself.

As for me, trying to grok and grade 200 freshman essays every week took its mental and emotional toll. There were screams in the night that probably rattled my neighbors. But USC also offered brilliant and stimulating professors and I would often leave my classes with my brain buzzing, every atom energized. So I had classes to teach and classes to learn from. No pain, no gain. I also managed to publish first one, then several fiction pieces that set the freelance writer wheels spinning forward. Spinning in an unexpected direction. Spinning on two wheels in fact. Motorized.

As it turned out I was putting around Los Angeles on a series of old motorcycles and somehow spun that into a series of short stories that appeared in well-known motorcycle and “men’s” magazines. After graduating, this motorized inclination led to seeking my first job as a feature writer at a motorcycle periodical publishing company. I rode in on my rather spiffy 1969 Norton which was a good opening move I thought. And when the publisher learned I had no magazine journalism/editor experience, I offered to go out, find a story, take photos and pen an article and be back the next day. If they liked what they saw, they could hire me. And they did. So

Lesson Three: Those who dare sometimes win writing jobs.

This first “gig” evolved into staff writing jobs at other “motorsport” publications, eventually as full Editor at several. I was writing about stuff I enjoyed and while I eventually went into full-time Freelancing, I still maintained my connections with many of those magazines and remain a full-time contributor to several.

Lesson Four: Write about what you know. Better yet, write about what you love.

Lesson Five: When you’re not writing about what you love, write about what you’re getting paid for.

Lesson Six: You can write about anything. If you know how to conduct research (and do interviews), you can write successfully about a wide range of subjects. For example, while I have penned tons of articles about people with tattoos and the artists who created them, I myself do not have a spot of ink on me. I have written about many musicians and bands, but can’t even whistle Dixie. I have written PR materials for a major pasta company, but can’t boil water. But I know how to listen, and I have developed a paradigm that always succeeds when conducting a “one to one.”

Lesson Seven: Learn the five cardinal points of a good interview. They involve, like any good newspaperman will tell you….Who, Where, When, Why, How? The rest of the interview, conducted in a relaxed “unprepared” conversational tone, takes its own organic form by careful listening, one question opening the next door. The magic involves truly caring about your interviewee, doing your background homework, and also remembering that for many, this is a very special moment in their life…when their story will appear in print…and it also emphasizes a writer’s professional and ethical responsibilities….your words can impact livelihoods and public image…and thus every word counts. Creative listening is the key. Importantly, remember the interview is not about you. While the interviewer sets the scene and applies the initial impetus, the story belongs to the interviewee. I’ve done literally thousands…in the field, over the telephone, over coffee…whatever and wherever the moment presents itself. Seize the day, seize the word.

Lesson Eight: There is no such thing as writer’s block. If you’re looking to expand your market base, go to a newsstand and look at what’s out there. Pick a magazine you want to write for then analyze the subject matter, style, tone, and the vibe of the readership, even the word count. Then go find a story that fits. Once upon a time, I discovered an old photograph taken in the late 1930s in Germany. It peeked my curiosity. To date I have written and had published two 500-page nonfiction books concerning WWII.

Lesson Nine: Follow the thread. If you have curiosity, that’s 90% of the game. The rest is leg work backed up by perseverance. Rejection slips: I could paper a wall with them, but more of my walls are covered with published works.

Lesson Ten: Self-discipline. Writing is both a vocation and an avocation. A real dyed in the wool writer is compelled to write…well, obsessed in fact. You get up every day, do your morning ritual to establish full-consciousness, and then get to work. At least 8 hours a day. At least five days a week. Like they say, it’s not just a job, it’s an adventure. You’ll excuse me, but it’s time to practice what I preach…I’m currently shaking up a story about vintage toys, another about horses and another about earthquakes….

Oh … my name. That would be Paul Garson. I am Googleable.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

paulgarsonproductions.com

paulgarsonproductions.com

Blog: Teaching Authors (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: picture books, writing rules, Jill Esbaum, Jeanne Marie Gruenfell, Add a tag

I'm the last one who'll be linking back to a favorite column of Jeanne Marie's as we bid her farewell. I'm choosing her entry from January 30, 2012, Unschooling, in which she talks about the "rules" of writing we're taught – and often need to unlearn.

This is especially true in picture book writing. Authors of published picture books frequently use:

contractions

incomplete sentences

sentences that begin with A

one word sentences

complicated words kids probably won't know

improper grammar

And that's just the tip of the iceberg. Some of my former English teachers would definitely not approve.

Think of picture books as performance art. How a story sounds, how page turns move it forward, are huge factors in its success. A certain elementary school librarian I know is the most masterful picture book reader I've ever heard/seen. She's also an actress in local stage productions, so that may be why timid is not in her vocabulary. She'll use multiple voices and volumes, dialects and intonations. Crazy faces. Dramatic pauses. Body language. She'll sing, crow, growl, or bring props from home, when necessary.

That's the kind of reader I'm writing for. One who brings a story to life for the kids who are hearing it, makes them feel a part of the action and empathize with the characters so deeply that they forget they're hearing a story somebody made up. We can only write stories to the best of our abilities and hope there are adults out there who will throw themselves in to the reading of them half as completely as my librarian friend.

When I was starting out, most of the manuscripts I submitted were "safe," meaning that I was careful not to break any rules. It wasn't until I loosened up that editors began to show interest.

Still, I remember dropping certain submissions into the mailbox and immediately wishing I could pull them out again. I worried that the down-home jargon in Stink Soup wouldn't be allowed. That I'd be asked to simplify some of the complicated (but era-appropriate) words in Ste-e-e-e-eamboat A-Comin'! and correct the improper grammar used by the characters in To the Big Top.

More recently, I wondered if a scene would be cut from I Hatched (Jan. '14). This book follows a newly-hatched killdeer chick as he delights in discovering his neighborhood and himself. At one point, he is surprised by ... well, the first time he poops. His story would have felt less authentic, to me, if he didn't poop. Still, I couldn't help wondering if the publisher would put the kibosh on that particular scene.

None of those things happened. Not one. Which freed me to stop worrying about rules and just tell stories the way they need to be told.

Jeanne Marie's final words regarding unschooling were these:

"While most of us can agree on the general precepts of 'good writing,' the first and best rule is ... there are no rules!

find your voice

find your truth

be true to your voice

always.'"

Amen, sistah.

Jill Esbaum

Blog: Teaching Authors (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Book Giveaway, rhyme, writing rules, Jill Esbaum, Add a tag

Back in October, I posted about the three elements – rhythm, rhyme, and story – that have to work together in character-driven rhyming picture books. In that post, I addressed getting a story's rhythm exactly right.

That leaves rhyme and story, so I thought I'd get back to those today. You all know how to rhyme, so I won't waste an entire post on the topic. Two things to keep in mind, though:

- Use proper syntax. If you have to twist a line for the sake of the end rhyme, find another way to get the thought across. Lines should read the way a person normally speaks.

- Talk "up" to your readers. Don't shy away from complicated words now and then if they fit the story, if kids will be able to glean meaning from context (and, most likely, an illustration), and especially if they're fun to say. In my Ste-e-e-e-eamboat A-Comin'!, which takes place in the 1800s, I rhymed songs and shouts with roustabouts; silk cravats with cowboy hats; and coffee, spoons with brass spittoons.

Rhyming stories have been my favorites since I was 5 or 6 years old (and was introduced to Horton).

Of the 16 books I've sold so far, 6 are rhyming picture books. So these days, I critique a lot of rhyming manuscripts – as a volunteer judge at Rate Your Story, in private and conference crits, and in summer workshops (note: my pb workshop is Aug. 2-4 this year). The number one problem with the stories I see is . . . well, the stories. It's pefectly natural. We get so caught up in perfecting rhythm and rhyme that story takes a backseat. Because boy, once we get those rhyming lines working together, most of us would rather undergo a root canal than make changes.

But the same rules apply to a rhyming story to one written in prose. So, a checklist:

- Does my main character have a goal to reach or some kind of problem? Did I get to it right away? Does he solve it himself?

- Do things go WRONG?

- Did I include believable/necessary dialogue? (Yes, this is tougher to do in rhyming stories. You thought this would be easy?)

- Does every word of every line move the story forward and convey a precise meaning? This is a biggie. Go through your story line by line. Are any lines/stanzas merely restating in a different way information already given? Condense or cut.

- Have I used specific verbs, vivid language, fresh similes and metaphors, alliteration, onomatopoeia? (If you have fun, your reader will, too.)

- Is my word count as low as possible? (Little pitchers have big ears, yes, but they also have short attention spans.)

- Is my POV consistent? (Try to avoid 1st person in rhyming stories. It can be done, but it's extremely tough to do without sounding overly-contrived.)

- Has my MC shown growth or changed somehow by the end of the story? (And am I not hitting the reader over the head with it?)

When it comes to crafting rhyming stories, practice really does make perfect. Examine a variety of published rhyming picture books. To get a feel for meter, read them aloud. Type them out. Study their plot structure. Learn to recognize and correct problem areas in your own work.

One final tip that gets its own line and bold print:

- Embrace revision. (Because, truly, there's NEVER only one way to say something.)

And before you know it, you'll be on the track to publication. Note that I didn't call it a "fast track." This IS publishing.

Jill Esbaum

P.S. Remember to enter our book giveaway for a chance to win Tamera Wissinger's delightful Gone Fishing!

Blog: Teach with Picture Books (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: writing, language arts, Ralph Fletcher, usage, mentor texts, writing rules, literary devices, verbs, Stenhouse, literary techniques, CCSS, Common Core, sentence writing, Steven Swinburne, Steven Krasner, Add a tag

- Encourage students to examine verb choice in novels, poems, picture books, and informational texts. I choose existing mentor texts and rewrite excerpts using “common verbs” (or, as Krasner would call them, place holders). Students are then challenged to replace these with more precise or colorful verbs.

- Direct your students to consider verb choice in their own writing, and work to find action words that are more exact. As a start, outlaw there is, there are, there were, there was phrases. A better alternative always exists. As do exceptions. Remember the first line of Holes?

- Teach children how to use a print thesaurus or online reference source (such as the Merriam Webster dictionary or Wordnik) for assistance in locating more exact expressions.

The term includes (but isn't limited to) puns, invented words, allusions, idioms, metaphors, similes, hyperbole, onomatopoeia, and alliteration. (A good deal of the text discusses sentence structure, which is key to complex and elaborated writing as defined by the Common Core standards).

While at first these devices might seem like window dressing, realize this: your best readers can recognize these devices (even if not by name) and understand them in texts, which leads to improved comprehension. Therefore, giving students practice with literary devices in writing will not only make them better writers, but better readers as well.

Among a ton of other issues in this book, Fletcher discusses the need for writing teachers and student writers to switch from the what (subject/meaning) to the how (language), and he follows up with many ways to make this important distinction. And to prove his point, the author provides this lovely extended metaphor:

In another section called Shimmering Sentences by Other Writers, he talks about how's he fascinated by writers who violate common ideas about usage, and get away with it. Not just get away with it, but produce stronger writing as a result! See Breaking All the Rules of Writing at my How to Teach a Novel site which discusses how author Andrew Clements does exactly that.

If you still think that the books' about "play" and not about "practice," consider what not just Ralph Fletcher, but other experts, had to say:

Blog: Utah Children's Writers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: voice, description, writing rules, 10 Commandments, Add a tag

By Julie Daines

Writing Conferences. We go. We listen. We obey. Maybe sometimes we obey too much.

My next few posts will be about when to break the writing commandments.

From the first bite, the rich, chocolate cake saturated his tastebuds with mouth-watering flavor.

The chocolate cake was delicious.

The object of avoiding the use of the word was is not to write forced prose, it is to use a stronger, better, more descriptive verb. So try to replace was with something better.

The chocolate cake tasted delicious.

Mack loved that chocolate cake from the first bite.

The sun beat down on the road. When I opened my car door, the heat assaulted me, wrapping its burning fingers around me and choking me. The hot asphalt attacked my bare feet trying to burn its way through my skin.

If Cami just ran out of gas in the middle of the desert and she faces imminent death by heat stroke, then this example is ok.

If all you want to do is get across how hot it is when Cami pulled up to the swimming pool, then keep it simple and direct--even if it means using was.

By the time Cami pulled up to the swimming pool, it was beyond hot.

- Use was, but only when it's the best and simplest way to get your point across. Sometimes, there is no better substitute.

- If you can, use a stronger verb in its place or rewrite the sentence.

- When you need to describe something important, pull out all the stops and elaborate--always keeping in mind the YA or MG voice.

Blog: Utah Children's Writers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: writing rules, storytellers, writing wednesday, wordsmiths, Add a tag

If we peel away the petty jealousy for those who collect royalties when we collect rejections, the complaint that someone broke the "rules" and still succeeded often comes down to storytellers and wordsmiths complaining about each other.

How often have you heard writers complain that a best-selling author tells a good story but is a terrible writer? How about critiques that someone writes beautiful prose but the story doesn't go anywhere?

You might say that storytelling vs.word smithing simply echos the distinction between commercial and literary fiction, where the former is all about the story and the latter is about how the story is told. But that observation only speaks to the stereotypes.

The deeper point is that storytelling and word smithing represent two fundamental approaches to the way we share narrative information. Storytelling is about selecting and presenting the best bits. Word smithing is about telling a bit well enough that it's interesting in its own right.

So, does this mean we have to choose sides?

Those of you who have been following for a while know that I don't like dichotomies unless they lead to a synthesis. The real answer is to make peace between the Hatfields and McCoys and strive for a good story, well told.

Blog: Book Binge (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: writing voice, Writing Rules, Show Don't Tell, Writing Myths, Generic Gestures, Writing, Add a tag

If you’re a writer, you’ve probably heard “Show, Don’t Tell’ a million times. It’s one of those maxims you can’t escape. But I’m going to stick my neck out and declare…

I think that advice has led to a lot of really terrible writing.

Before you come at me with your sharpest pitchfork, let me explain my madness. I do believe, in many ways, it is good and useful and wise to ‘show’ things. There is a time and place for the camera pan, the action shot, the external focus. But a novel is not a screenplay. A movie is a string of external cues–visuals and sound–that tells a story. The viewer relies on these cues to make sense of the plot and all its underpinnings–the internal, intangibles such as emotion and theme.

The novel is an entirely different medium. A novel conjures a singular experience, not just through external description (what a camera can capture), but also by internal perception (the heart and soul an ordinary telephoto zoom can’t record). In a novel, there’s a lens that trumps all.

The human lens.

The fictive stream of consciousness. The thingamathink that pulls us under the skin of a character. The internal processor that that recalls events and interprets every moment of action in the context of a character’s deepest hopes, dreams, memories and fears.

Yet...motivated by well-intentioned advice, so many writers neglect this lens and start out writing novels like screenplays. They try to live by ‘show’ alone–moving characters here and there on a stage, describing everything in objective, surface-level terms the way a wide-angle camera shot would. This cheats the reader and sentences them to a parade of colorless, cliched gestures and descriptions.

John’s eyes widened in anxiety. Mary’s heart hammered. Glen’s jaw clenched. Raul’s brow quirked. Anna’s lips curled in a smirk. Neville clenched his fists at his sides. Snakes slithered in Jonah’s stomach.

Ugh. These gestures and reactions are all generic. They illuminate nothing about character, personality, conflict or plot. As Francine Prose so aptly writes in Reading Like a Writer, “they are not descriptions of an individual’s very particular response to a particular event, but rather a shorthand for common psychic states.”

Meaningless shorthand. Yes. But darn it, they show and don’t tell. And that’s the rule, right?

WRONG. WRONG. WRONG.

I am nothing more than an puny, unpublished, unknown Writer/Librarian/Beatle-Maniac, but I will not recant. I will not! Because writing fiction is a form of storyTELLING. I agree with Joshua Henkin when he calls ‘Show, Don’t Tell’ the ‘great lie of writing workshops.‘ I say go ahead and slip under that murderer’s/ballerina’s/magician’s/vampire’s skin, tap into that stream of consciousness and TELL that story, infusing

Blog: Writing for Children with Karen Cioffi (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: children's writing, writing for children, writing rules, fiction writing for children, Add a tag

Fiction writing for children is a large genre that is broken into several smaller, specific genres, such as picture books, chapter books, and middle grade. And, each specific genre has its own set of rules you must adhere to in order to keep your story out of the editor’s trash pile.

Fiction writing for young children is probably a more scrutinized genre in that there are a lot of things to watch for.

Here is a list of 10 rules to refer to when fiction writing for young children:

1. This is probably the most important item: be sure that your story does not suggest dangerous or inappropriate behavior.

Example one: The protagonist (main character) sneaks out of the house while his parents are still sleeping.

Example two: The main character is alone in the street or a vacant lot.

This is a no-no!

2. Make sure your story has age appropriate words, dialogue and action.

For more information on age appropriate words, check out: Finding Age Appropriate Words When Writing for Children

3. The protagonist should have an age appropriate problem or dilemma to solve at the beginning of the story, in the first paragraph if possible. Let the action/conflict rise. Then have the protagonist, through thought process and problem solving skills, solve it on his/her own. If an adult is involved, keep the input and help at a bare minimum.

Kid’s love action and problem solving!

4. The story should have a single point of view (POV). To write with a single point of view means that if your protagonist can’t see, hear, touch or feel it, it doesn’t exist.

Example: “Mary crossed her eyes behind Joe’s back.” If Joe is the protagonist this can’t happen because Joe wouldn’t be able to see it.

5. Sentence structure: Keep sentences short and as with all writing, keep adjectives and adverbs to a minimum. And, watch your punctuation and grammar.

6. Write your story by showing through action and dialogue rather than telling.

If you can’t seem to get the right words to show a scene, try using dialogue instead.

7. You also need to keep your writing tight. This means don’t say something with 10 words if you can do it with 5. Get rid of unnecessary words.

8. Watch the timeframe for the story. Try to keep it within several hours or one day.

9. Along with the protagonist’s solution to the conflict, he should grow in some way as a result.

10. Use a thesaurus and book of similes. Finding just the right word or simile can make the difference between a good story and a great story.

Using these techniques in your fiction writing for young children will help you create engaging and publishable stories.

Another important tool to use in your writing tool belt is joining a children’s writing critique group. No matter how long you’ve been writing, you can always use another set of eyes. If you’re a beginning writer and unpublished, you should join a group that has published and unpublished members. Having published and experienced writers in the group will help you hone your craft.

Are you really interested in writing for children? If you answered yes, check out:

0 Comments on Fiction Writing for Young Children - Ten Basic Rules as of 1/1/1900

Blog: Guide to Literary Agents (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Writing Your First Draft, write better, Haven't Written Anything Yet, Writing for Beginners, How to Improve Writing Skills, Donald Maass, writing rules, What's New, Add a tag

Is it always better to show than tell? Do you really have to write every day? Experts prove there's merit in both playing by the book and staging a writing rebellion. Read more

Add a CommentBlog: Teaching Authors (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: writing rules, Jeanne Marie Grunwell Ford, Add a tag

After the flurry of exciting awards-related activity this week, I know many of us are looking forward to (variously) the Superbowl, the Academy Awards, Valentine's Day... I, in my third week of classes, am already looking forward to Spring Break. January/February/March is a long stretch for teachers and students alike, yes?

I've had a particularly rocky start to the semester with campus construction and new computer systems, locked doors and snow and, oh, getting stranded on the wrong coast one Monday morning. I had to give extra credit to the student who could magically make my projector light up. (What will I ever do if he is absent?)

In Week 1, I gave my typical spiel -- "Now that you have mastered the five-paragraph essay format, you are going to have a little more freedom to try new things, to build on the structure you've learned but to break the rules a bit." Typically, I have many students who balk at the idea that an essay does NOT (gasp) have to be five paragraphs long. Many also have incredible difficulty with the notion that the introductory paragraph, the body paragraphs, and the concluding paragraph of an essay should NOT actually repeat the same thought three times.

One of my rule-loving students (of whom I am already quite fond) raised her hand this week and said, "Since we're doing everything differently from everything I've been taught... what about contractions?"

We are, mind you, writing a narrative essay based on personal experience. We have already talked about audience and tone. I said, 'This is an informal essay. Of course you may use contractions.' Students were shocked. 'We were taught never, ever to use contractions.' 'We were SCORNED for using contractions.' I asked them to raise their hands if they were told never, under any circumstance, to use a contraction. Fully 90% of students did so.

Goodness gracious. Contractions are the least of the problems I typically see in student writing. I understand that we are trying to prepare students for a wide variety of writing tasks in life: literary analyses, drug trial reviews, briefs, summaries, business memos, nursing intake notes, police reports, textbooks, articles, novels. Encouraging students to assess the genre and the necessary conventions is the FIRST thing we should be teaching.

And so I wonder about the "rules" that are being drummed into students in high school and developmental writing courses. I remember wondering the same as a student. If I am supposed to be writing in clear and complete sentences, why does Faulker get to write a five-and-a-half-page run-on? And why can I understand only every third sentence of the jargon-stuffed journal article that I must read for my psychology class?

While most of us can agree on the general precepts of 'good writing,' the first and best rule is... there are no rules!

find your voice

find your truth

be true to your voice

always

-- Jeanne Marie

Blog: Musings of a Novelista (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Writing, writing rules, Add a tag

Happy New Year everyone! Let’s start off the year with some focus. Here are some writing rules for 2010.

Like this poster? You can order it here.

Blog: Day By Day Writer (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: writing rules, Alyson Noel Evermore, Neil Gaiman The Graveyard Book, Newbery Medal winner, books, Writing, Add a tag

Yesterday I wrote about the so-called “rules” of writing that are broken by many best-selling books on retail shelves now. Here’s two more:

Don’t date your story with product placement: Writing that your character has a crush on Zac Efron can give the story a touch of authentication, but the reason this is considered a no no is that in 50 years, Zac Efron might not be in the public consciousness anymore (no offense, Zac). So, by using something or someone in today’s culture, you’re dating your book to this time period, and one of the goals for a great book is to be timeless, to be the kind of book that can be read and enjoyed 70 years from now as well as it is today. C.S. Lewis wrote The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe in 1950 and it’s still on shelves today, 59 years later — something we’re all striving for in our stories. So, the “rule” is, don’t limit the readership by dating the story with current people and objects. Yet, there are many books on shelves with these references. I just finished reading Alyson Noel’s Evermore — if you haven’t read it, I highly recommend you get a copy. It’s a fun page-turner — and in it, Alyson has placed numerous references to things from today’s culture, for example a reference to Pirates of the Caribbean’s Orlando Bloom. Is Bloom going to be timeless? Will he be as memorable as, say, James Dean in 60 years? (No offense, Orlando.) It comes down to author’s choice. I have a reference to the tornado in The Wizard of Oz (another classic novel) in my novel and have been told the “rule” a few times. I’m happy with my reference because I think The Wizard of Oz is timeless enough that it doesn’t date the story. But it’s another “rule” that can be broken.

Don’t write sentences that are too long: This “rule” is for children’s books, which is what I write. The “rule” is based on the idea that kids won’t read a book that has long sentences. I don’t know if this is really true, but I hope that it isn’t. Personally, I don’t think writers should write down to children by keeping sentences short and words easy. As a kid, I remember looking up words in the dictionary many times when I read a book. The book expanded my knowledge, and that can’t be a bad thing. Now, here’s an example of the “rule” broken. Here’s a sentence from this year’s Newbery Medal winner, The Graveyard Book:

Then he moved through the night, up and up, to the flat place below the brow of the hill, a place dominated by an obelisk and a flat stone set into the ground dedicated to the memory of Josiah Worthington, local brewer, politician and later baronet, who had, almost three hundred years before, bought the old cemetery and the land around it, and given it to the city in perpetuity.

That’s a long sentence, and Neil Gaiman could have broken it up into shorter sentences, but he chose not to. And he has plenty more in the book — the Newbery Medal winning book.

So, again, “rules” are there for a reason but can be broken. First, of course, you have to know them and know why they’re rules, then you can make a choice about whether to follow them or break them.

Write On!

Blog: I.N.K.: Interesting Non fiction for Kids (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: steve jenkins, writing non-fiction, clarity, writing rules, Add a tag

Of course, this isn’t really about anything being simple. I just thought I’d take a magazine cover-line approach and use a completely misleading headline to increase readership.

I’m giving a talk soon about writing children’s non-fiction, and as an exercise I’ve tried to articulate a list of rules & guidelines I follow when writing. These are rules that apply to my own writing — I’m not suggesting that anyone else should follow them. Well, maybe one or two of them.

• Don’t underestimate the ability of young children to understand abstract concepts.

• Put new concepts and information into a context that makes sense to children. Try to use metaphors or comparisons with something familiar. Sadly, the standard measurement unit of my childhood for things of modest size — the bread box — is unfamiliar to most kids today.

• Don’t mix different units of measurement or meaning in the same comparison. I see this all the time in adult writing, even in publications like the New York Times, and it always annoys me: “There are only 500 animal A’s found in the wild, and the population of animal B has decreased by 80%.”

• Clarify terms that seem simple but have multiple interpretations. This is a common problem with scale-related information: “Animal A is twice as big as Animal B”. What does ‘big’ mean? If it’s based on length, and if the animals are similarly proportioned, then animal A weighs eight times as much as animal B.

• Introduce a few new terms and vocabulary words, but not too many for the reading level of the audience. If possible, use new terms without formal definition in a context that makes their meaning clear. It’s more fun for kids to figure out for themselves what a word means.

• Don’t anthropomorphize. Like I said, these rules are for me. There are lots of great natural science books that use the first-person voice of animals, natural forces, even the universe. But these books make it clear from the beginning that there is poetic license involved, and that the reader is being invited to use their imagination to see the world from the perspective of some other entity. I’m more concerned about casual references to the way animals ‘feel’, or what they ‘want’, in the course of what purports to be a objective examination of their behavior.

• If possible, anticipate the questions suggested by the facts being presented and answer them. This can be a never-ending sequence, one answer suggesting another question, so at some point one has to move on, but if we point out that an animal living in the jungle is brightly colored, it’s great to be able to say how color helps the animal (as it must, in some way, or it would have been selected out). Does its color warn off predators, attract a mate, or — counter-intuitively — help it hide? A colorful animal that lives among colorful flowers may be hard to spot.

• Try to avoid the standard narrative. For many subjects, a typical story line seems to have developed. Or there is an accepted linear sequence of introducing concepts. Teaching math is an example: arithmetic, geometry, algebra, calculus. There is some logic to this, but even a child that can’t do long division can understand some of the basic applications of (for example) calculus. Often the same creatures or phenomena are used to illustrate a particular point. Symbiosis: the clown fish and anemone. Metamorphosis: butterfly, frog.

• Don't oversell science as fun, or make it goofy or wacky. There is thinking involved, and work. The fun and satisfaction come from understanding new things and seeing new connections.

• Don’t confuse the presentation of facts with the explanation of concepts.

• Don’t follow lists of rules.

That’s it! Just follow these simple guidelines, and everything will be perfect. (Results may vary. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. For external use only.)

Blog: Scribbled Business (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: adobe illustrator, crystal driedger, grizzly bear, bear, black bear, Royal Alberta Museum, illustration, style, vector, bear, crystal driedger, adobe illustrator, Royal Alberta Museum, grizzly bear, black bear, Add a tag

If there's one wonderful aspect having a part-time job, it would be the ability to diversify yourself. While it's nice to be able to see people other than your family on a 24 - 7 basis, this is not the biggest benefit I've discovered by working at the Royal Alberta Museum. While my job is primarily graphic design in nature I have been able to complete the odd illustration here and there. To top off this bunch of pure goodness, it's usually different stylistically than I do during my business hours as an illustrator. This really gives me the chance to experiment, which is very needed in this business of illustration.

The bears above were for a board game that the education department uses to educate children about grizzlies and black bears. It's more of a simple, sihouette approach and yet I found it fun (sort of like a puzzle).

Blog: Scribbled Business (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: harry potter, rent, Tunisia, Edu Kit, Royal Alberta Museum, Add a tag

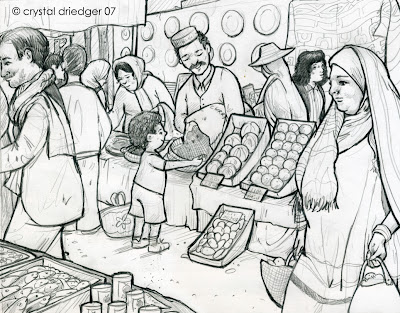

Here's a little taste of a b&w line drawing series I'm currently working on for the Royal Alberta Museum of Alberta. For all of you teachers out there interested in renting an "Edu" Kit about Tunisia (a country in Northern Africa) contact me and I'll give you some more information on how to rent this educational/fun set.

And a little site note to those of you who, like myself, feed off of the creative writings of J.K.Rowling: you shall not be disapointed. This installment is packed with adventure and will have you at the edge of your seat biting your nails. At moments you'll weep while others will have you laughing and rolling on the floor. I'm not afraid to admit that I am already on my second read of the book... WOW! There are some great surprises in the end of the book.

Nice post, Jill. I can hardly wait to see I HATCHED!

Thanks, Cindy!