Swedish psychologist Carl-Johan Forssén Ehrlin surprised the book publishing world this summer as his book for children and their parents shot to number one on Amazon. The Rabbit Who Wants to Fall Asleep is a self-help book that gives parents a script to follow as they try to get a child to go to sleep. Because of its performance on Amazon, Penguin has picked up the book for a reported seven-figure deal.

Of course, I had to read it. Buzz does sell books.

Rabbit (if I can casually call it by the name of the insomniac main character) reminds me of the Academy Awards ceremony. Screenwriters, directors, actors and actresses, cinematographers and the full complement of support staff for a major move were awarded the highest honor that filmmaking can bestow, Academy Awards. And for every movie about a cause—from elderly rights to gay rights and beyond—the person being honored felt compelled to stand up and explain why their cause was so important and timely. . . thereby negating the art for which they’d just been honored.

Why did they not trust their art to plead their cause in deeper and stronger ways than a week diatribe made during a gala ceremony? It baffles me.

In the same way Ehrlin explains why a good bedtime story works. He has built into the script certain keywords – sleep now, yawn, now—which should help put the child in the right frame of mind. Further, he uses some words because they sound calm and slow, thus reinforcing the desired frame of mind. Repetition finds its place as a tool to calm and convince a child to fall asleep.

But why does Ehrlin feel the need to explain it all so blatantly? Perhaps, it’s because parents don’t go behind the scenes for a children’s bedtime story; they don’t understand, and therefore don’t trust, that the writer really knows what s/he is doing when writing this kind of story.

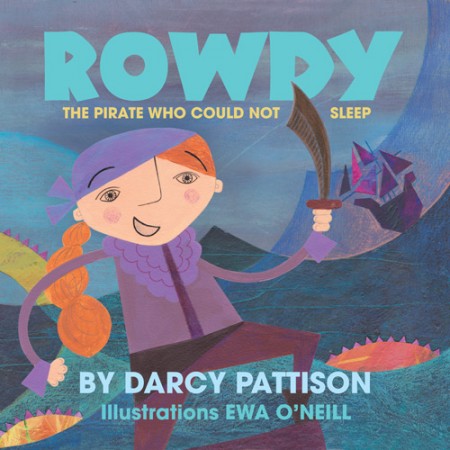

In fall 2016, I’ll join the ranks of authors with a bedtime story, ROWDY: The Pirate Who Could Not Sleep. Let me show you what’s behind the curtain of my writing process.

The Sounds of Words

As a young writer, I once heard Newbery medalist Lois Lowry speak about a story that ended in a quiet moment that she hoped would calm a child and help them sleep. She avoided harsh-sounding words and used soft words. That’s right. The way the words sounded was just as important, if not more so, than the meaning of the words.

Poets John Ciardi and Miller Williams said a similar thing in their classic book, How Does a Poem Mean. They emphasize the “connotations speaking to connotations,” an effect they say will create imagery and symbolism. In other words, it matters whether you use the word “fire” or “inferno” because of how it sounds, its connotations and its definitions. Just as important, though, is how it affects the rhythm pattern of your piece of writing. Fire has only one syllable, while Inferno has three syllables; using one over the other affects the rhythm patterns of the writing.

I have a B.A. in Speech Pathology and an M.A. in Audiology; one of the most useful classes from my college years was phonics, or the study of how sounds are made in the human mouth and how to record those sounds with the International Phonetic Alphabet.

For a bedtime story, you want to avoid harsh sounding consonants, what phonetics calls fricatives or affricatives: f, v, th, t, d, sh, zh, ch, j, s and z. Other sounds to avoid are the plosives: b, p, t, d, k, g. You can’t avoid these two major groups of consonants entirely! But you can minimize them, especially when you want the words to be the softest.

Another distinction phonetics makes is among voiced or unvoiced consonants. Put your hand on your throat and say T –T –T ; repeat with D – D – D. Do you feel that your vocal cords vibrate for the D, but not for the T? T is unvoiced; D is voiced. Unvoiced consonants are softer, and more suited to bedtime stories.

The softest sounds are the glides: w, l, r and y. These are the real winners for a calming bedtime story.

For vowels, you should understand that some vowels involve lots of tension in the mouth, while some are created with a relaxed mouth. Say a long A; now say AW. Do you feel the difference in the mouth’s tension?

Ehrlin merely takes a clue from phonetics/linguistics and uses relaxed vowels, along with soft consonants.

Why is a rabbit the right animal for Ehrlin to choose for a bedtime story? Rabbit is a relatively calm word: Glide R; short A is relatively relaxed; B is a plosive, but it’s buried in the word’s middle; UH is a relaxed vowel; T is a plosive but because it’s unvoiced, or your vocal cord doesn’t vibrate for it, it’s relatively calm.

My Fall 2016 bedtime story, ROWDY: THE PIRATE WHO COULD NOT SLEEP, is about Captain Whitney Black McKee. She’s a rowdy pirate captain who fights sea monsters and returns to home port, but finds that she can’t sleep. Her crew goes a’thievin’, in search of a lullaby to help her sleep. In the end, the cabin boy brings back her Pappy who sings her a lullaby.

Here’s that last stanza, which you cannot read it harshly because the words, the phrasing and the story that I wrote demand that you say it softly.

Then Pappy sang of slumber sweet,

while stars leaned low and listened.

And as the soft night gathered round.

The pirates’ eyes all glistened.

GREAT bedtime stories include. . .

- Child-in-lap relationship. Mem Fox, the beloved Australian writer, talks about the importance of keeping in mind the child-in-the-lap relationship. She means that when you read a story to a child, you are also developing a relationship with that child. She likes to end stories with something that will make the child turn to the adult and give them a hug or say, “I love you.”

Her beloved book, Kaola Lou, has the refrain, “Kaola Lou, I do love you.” And of course, it’s hard to read without also saying to the child in your lap, “I love you.”

Her beloved book, Kaola Lou, has the refrain, “Kaola Lou, I do love you.” And of course, it’s hard to read without also saying to the child in your lap, “I love you.” - Language development. The great bedtime stories take into account the whole child, not just his or her ability to go to sleep quickly. Instead, they develop a child’s language. Because these are books provided at developmentally appropriate times in a child’s life, it’s an opportunity to entice them with language: the sounds of their native language, the vocabulary, the rhythm patterns and so on. Kindergarten teachers spend time teaching nursery rhymes (Jack be nimble; Jack be quick; Jack jump over the candlestick.) because it develops skills in language.

In a like manner, the classic Goodnight Moon! by Margaret Wise Brown uses rhythm, refrains and much more. Consider the humor of this line: “Goodnight, nobody.” It makes for a story that you don’t mind reading for the 1000th time. - Story. As children develop language, an important skill is the ability to understand stories. This involves sequencing of events (beginning, middle, end), understanding cause-effect relationships, character motivations and much more.

Llama, Llama Red Pajama by Anna Dewdney has an appropriately simple story. Baby Llama is tucked into bed, but when Mama leaves the room, he calls that he needs a drink of water. The plot complication is just that Mama is delayed in bringing up the water, so Baby Llama panics. When Mama shows up, she reassures him that she is “always near, / even if she’s / not right here.” It’s a gentle, reassuring story. And while it tells the story, it also gives kids experience in understanding Story.

Llama, Llama Red Pajama by Anna Dewdney has an appropriately simple story. Baby Llama is tucked into bed, but when Mama leaves the room, he calls that he needs a drink of water. The plot complication is just that Mama is delayed in bringing up the water, so Baby Llama panics. When Mama shows up, she reassures him that she is “always near, / even if she’s / not right here.” It’s a gentle, reassuring story. And while it tells the story, it also gives kids experience in understanding Story. - Vocabulary building. Kids love big words—in the right context.

Jane Yolen’s story, How Do Dinosaurs Say Good Night? provides great fun with the names of various dinosaur species. What kid can resist words such as Allosaurus, Pteradon, Apatosaurus, and Tyrannosaurus Rex? But Yolen also includes words appropriate for the bedtime hour. “Does a dinosaur slam his tail and pout?”

You can’t read this without screwing up your face in a pout, thus teaching the meaning of a vocabulary word in a natural context.

My own bedtime story is titled ROWDY: The Pirate Who Could Not Sleep (to be released Fall, 2016). Will kids know the meaning of “rowdy”? Doubtful. But within the story’s context, they’ll learn it. Bedtime stories, then, are a comfortable and natural context for teaching new words.

Great children’s book authors create works that don’t need the artificial crutches of bold and italic fonts to tell the adult reader how to present the story. Instead, it’s right there in black and white on the page. It tells a great story that reinforces language and vocabulary development. And when it’s done right, a great bedtime story gives an adult an opportunity to give the kid a hug and a kiss and say, “I love you.”