new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: protests, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 6 of 6

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: protests in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Cody Merrow,

on 4/10/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

beijing,

Communist,

protests,

Social Sciences,

East Asian Studies,

*Featured,

economic growth,

Xi Jinping,

A Touch of Sin,

China's Smoldering Volcano,

John Birch,

Marvin Whyte,

Terry Lautz,

Books,

china,

Politics,

Add a tag

The United States is far from perfect. But China still lacks an independent legal system, adequate protection of human and labor rights, genuine freedom of expression, and predictable means to address grievances. Until such reforms can be accepted in Beijing, resentment will continue to rise and China’s smoldering volcano may eventually erupt.

The post China’s smoldering volcano appeared first on OUPblog.

By: KatherineS,

on 3/6/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

protests,

personal identity,

austerity,

*Featured,

Business & Economics,

arab spring,

protester,

Science & Medicine,

Occupy Wall Street,

eurozone,

Psychology & Neuroscience,

anti-immigration,

Christian von Scheve,

Collective Emotions,

collective identity,

complex affective processes,

Mikko Salmela,

nationalist,

scheve,

mikko,

salmela,

shankbone,

Books,

emotions,

Politics,

Current Affairs,

Spain,

conservative,

EU,

Greece,

Portugal,

financial crisis,

Add a tag

By Mikko Salmela and Christian von Scheve

Nationalist, conservative, and anti-immigration parties as well as political movements have risen or become stronger all over Europe in the aftermath of EU’s financial crisis and its alleged solution, the politics of austerity. This development has been similar in countries like Greece, Portugal, and Spain where radical cuts to public services such as social security and health care have been implemented as a precondition for the bail out loans arranged by the European Central Bank and International Monetary Fund, and in countries such as Finland, France, and the Netherlands that have contributed to the bailout while struggling with the crisis themselves. Together, the downturn that was initiated by the crisis and its management with austerity politics have created an enormous potential of discontent, despair, and anger among Europeans. These collective emotions have fueled protests against governments held responsible for unpopular decisions.

Protests in Greece after austerity cuts in 2008

However, the financial crisis alone cannot fully explain these developments, since they have also gained momentum in countries like Britain, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden that do not belong to the Eurozone and have not directly participated in the bailout programs. Another unresolved question is why protests channel (once again) through the political right, rather than the left that has benefited from dissatisfaction for the last decades? And how is it that political debate across Europe makes increasing use of stereotypes and populist arguments, fueling nationalist resentments?

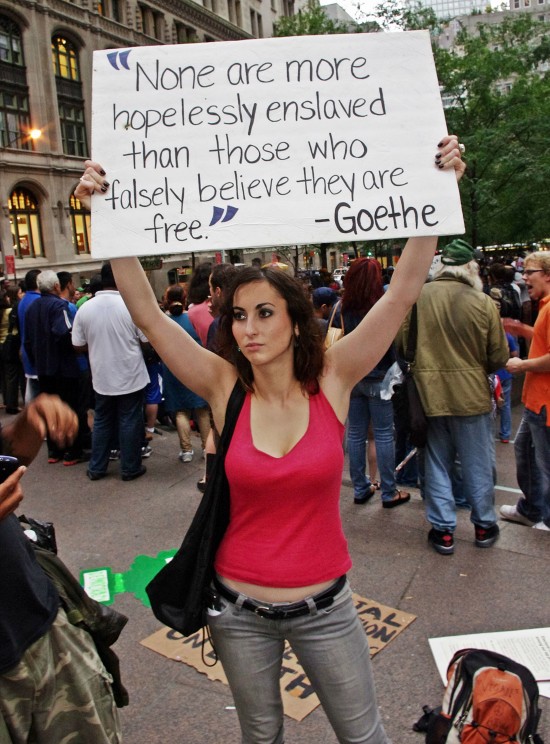

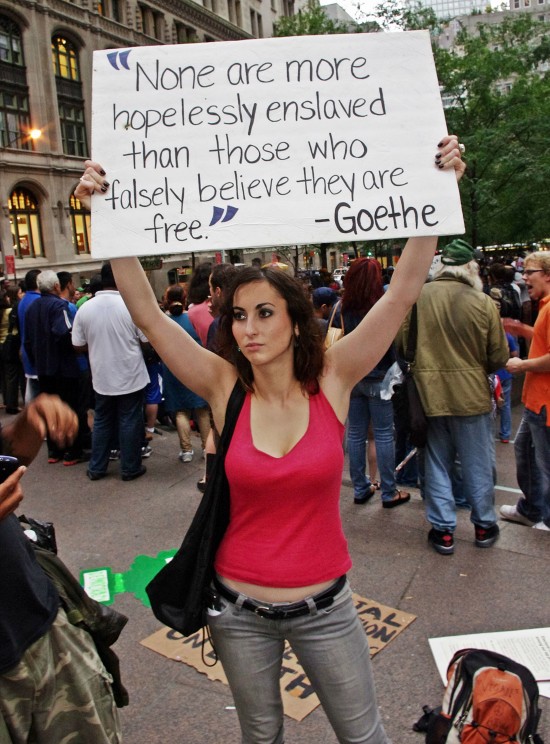

A protester with Occupy Wall Street

One way to look at these issues is through the complex affective processes intertwining with personal and collective identities as well as with fundamental social change. A particularly obvious building block consists of fear and insecurity regarding environmental, economic, cultural, or social changes. At the collective level, both are constructed and shaped in discourse with political parties and various interest groups strategically stirring the emotions of millions of citizens. At the individual level, insecurities manifest themselves as fear of not being able to live up to salient social identities and their inherent values, many of which originate from more secure and affluent times, and as shame about this anticipated or actual inability, especially in competitive market societies where responsibility for success and failure is attributed primarily to the individual. Under these conditions, many tend to emotionally distance themselves from the social identities that inflict shame and other negative feelings, instead seeking meaning and self-esteem from those aspects of identity perceived to be stable and immune to transformation, such as nationality, ethnicity, religion, language, and traditional gender roles – many of which are emphasized by populist and nationalist parties.

The urgent need to better understand the various kinds of collective emotions and their psychological and social repercussions is not only evident by looking at the European crisis and the re-emergence of nationalist movements throughout Europe. Across the globe, collective emotions have been at the center of major social movements and political transformations, Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring just being two further vivid examples. Unfortunately, our knowledge of the collective emotional processes underlying these developments is yet sparse. This is in part so because the social and behavioral sciences have only recently begun to systematically address collective emotions in both individual and social terms. The relevance of collective emotions in recent political developments both in Europe and around the globe suggests that it is time to expand the “emotional turn” of sciences to these affective phenomena as well.

Christian von Scheve is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Freie Universität Berlin, where he heads the Research Area Sociology of Emotion at the Institute of Sociology. Mikko Salmela is an Academy Research Fellow at the Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies and a member of Finnish Center of Excellence in the Philosophy of Social Sciences. Together they are the authors of Collective Emotions published by Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Protests in Greece after austerity cuts in 2008. Photo by Joanna. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) A protester with Occupy Wall Street. Photo by David Shankbone. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons)

The post Collective emotions and the European crisis appeared first on OUPblog.

I'm one of those. The personal boycotter. There are certain restaurants I won't eat in, certain large chains I won't shop in, and certain organizations my family won't participate in. I don't agree with the way these places do business, or with their policies. So I'm not giving them my money or my family's time.

I'm one of those. The personal boycotter. There are certain restaurants I won't eat in, certain large chains I won't shop in, and certain organizations my family won't participate in. I don't agree with the way these places do business, or with their policies. So I'm not giving them my money or my family's time.

I keep it quiet. I don't usually mention it to anybody outside of my family or closest circle of friends. I'm not doing this to try and change other people's behavior.

And I know these places don't miss my occasional combo meal or even my kid building a balsa wood car. They're humming along just fine without us. So why bother?

Well, for one thing, I want to teach my kid to align his actions with his beliefs. When he can make a choice about where to spend his money or time, I hope he will always consider what he is supporting--even if his contribution if only a drop in a bucket.

It also makes me feel a little less helpless. I've signed petitions and written letters but that doesn't always change things. Neither does my personal boycotting, probably. But at least it's one tiny little cut against the things that anger me.

Could my personal boycotts backfire? Certainly. So far our kid hasn't gotten angry with us about these choices--but we are keeping him from places and organizations that some of his friends get to enjoy. I dread the day he decides he's sick of our principles. And I worry, too, that it could isolate us from neighbors and potential friends that don't feel as strongly--or the same way--as us.

But those aren't good enough reasons to stop. So I'll keep spending my money where I feel good about it, and signing my kid up for the organizations I'm proud to see him participate in.

Meanwhile, I'll hope that someday things will change. I'll be the first one in line for that combo meal and balsa wood car kit.

If you'd like to read more, Bloomberg has a great article about the history of American boycotts and their sometimes unintended consequences.

By: Lana,

on 12/6/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

nato,

protests,

*Featured,

libya,

gaddafi,

Law & Politics,

arab spring,

Jared Genser,

Muammar Gaddafi,

Responsibility to Protect,

gaddafi’s,

rtop,

libyan,

genser,

atrocities,

Current Affairs,

Add a tag

By Jared Genser

With the recent end of the NATO mission in Libya, it is an opportune moment to reflect on what took place and what it may mean for global efforts to prevent mass atrocities. Protests demanding an end to Muammar Gaddafi’s 41-year reign began on February 14th and spread across the country. The Libyan government immediately dispatched the army to crush the unrest. In a speech a week later, Gaddafi said he would rather die a martyr than to step down, and called on his supporters to attack and “cleanse Libya house by house” until protestors surrender. Some six months later, Gaddafi’s response to the contagion from the Arab Spring uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt triggered a series of measures being imposed by the UN Security Council, including what became a NATO-sponsored “no-fly” zone. These measures ultimately resulted in Gaddafi’s ousting from power.

The overarching justification for the international intervention was the “responsibility to protect” (RtoP), a still-evolving doctrine which says all states have an obligation to prevent mass atrocities, including genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and ethnic cleansing. In the wake of the Libya action, however, a fierce debate has raged over whether its use in this case will help or hurt this approach from being used to help future victims of mass atrocities.

Since its adoption, the doctrine has most notably applied in the case of Kenya’s post-election violence in 2007-2008 and as justification for lesser action in places such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kyrgyzstan, Guinea, and Côte d’Ivoire. Its application in Libya, however, was only the second time it has been explicitly invoked by the Security Council regarding the situation in a specific country.

In response to Gaddafi’s unyielding assaults on civilians in Libya, the Security Council adopted a unanimous resolution which imposed an arms embargo on Libya, targeted financial sanctions and travel bans against Gaddafi, his family members, and senior regime officials, and referred the situation to the International Criminal Court for investigation of those involved in what was referred to as possible crimes against humanity. In the subsequent six weeks, while the international community debated how to proceed, Gaddafi moved relentlessly moved to quell the uprising, reportedly killing thousands of unarmed civilians.

With the urgency created by Gaddafi’s threats, the presence of his troops just outside Benghazi and a critical public statement by the Arab League urging the immediate imposition of a no-fly zone on Libya, the Security Council adopted a new resolution. Among other actions, it authorized UN member states to take “all necessary measures” to protect civilians, created a no-fly zone over Libyan airspace, and urged enforcement of an arms embargo and asset freeze on Libyan government as well as on key officials and their families.

It was these efforts, after substantial success and failure, which ultimately resulted in the overthrow of Gaddafi many months later. It is in that context there have been a range of perspectives regarding the Libyan intervention which will ultimately shape its legacy.

First, there is a concern that in the name of civilian protection, RtoP was used to justify a regime-change agenda, which was never the purpose of the doctrine. Second, there has been a global focus on the “sharp end” of RtoP being deployed in Libya. This broader agenda of atrocity prevention can easily be lost when an exception of military intervention, at one extreme of a possible response, swallows the entire doctrine, which is much more comprehensive. And third, there is a conc

By: Maryann Yin,

on 2/4/2011

Blog:

Galley Cat (Mediabistro)

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Libraries,

peace,

UK,

families,

demonstrations,

protests,

read-ins,

Voices for the Library,

400 planned library closures,

February 5th,

save our libraries day of action,

Add a tag

Tomorrow (February 5th), readers around the U.K. will gather to protest the more than 350 possible library closures in England–Voices for the Library’s special “save our libraries day of action.” The group’s Facebook page already counts 740 participants.

Tomorrow (February 5th), readers around the U.K. will gather to protest the more than 350 possible library closures in England–Voices for the Library’s special “save our libraries day of action.” The group’s Facebook page already counts 740 participants.

The day of action will feature read-ins around the country. In addition, author appearances and storytelling events are also planned.

Librarians and information professionals formed Voices for the Library last August with this goal: “[To create] a place for everyone who loves libraries to share their stories and experiences of the value of public libraries. We don’t want to lose our libraries, and we aim to ensure future generations continue to enjoy access to free unbiased public libraries and librarians.” (via Publishers Weekly)

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

By: Rebecca,

on 6/4/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

china,

Reference,

Politics,

A-Featured,

Online Resources,

World History,

Tiananmen Square,

protests,

1989,

June 4,

tiananmen,

secretariat,

pro‐democracy,

Add a tag

On this day in 1989, 100,000 Chinese citizens gathered in Tiananmen Square. I wanted to learn more about the event so I turned to Oxford Reference Online which led me to The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics edited by Iain McLean and Allistair McMillan. Below the entry on Tiananmen Square is excerpted.

Tiananmen Square

Tiananmen, the Gate of Heaven’s Peace, the main square of Beijing, where in the early hours of 4 June 1989 a huge pro‐democracy demonstration was repressed by armed force.

The democracy movement began during the Cultural Revolution when many Red Guards, while accepting Mao ’s instructions to attack the Party establishment, realized that rebellion would be fruitful only if it aimed at the achievement of democracy. The first expression of this was the Li Yi Zhe Poster of 1974 which while supporting the aims of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution argued for democratic institutions. The second was Chen Erjin’s book, Crossroads Socialism, written just before the death of Mao and published during the Democracy Wall demonstrations of late 1978 . This sought to extend Marxism by arguing that violent socialist revolution inevitably produces yet another exploitative social formation, the rule of the authoritarian revolutionary elite. A second revolution is always necessary to put real power in the hands of the people, through the establishment of democracy.

Mao’s successors, themselves victims of the Cultural Revolution, had an interest in strengthening the rule of law, and an interest in relaxing political control enough to prevent another outbreak. Deng Xiaoping had a personal interest in mobilizing democratic sentiment against the left. He supported the Democracy Wall protest of late 1978 until the young radical factory worker Wei Jingsheng demanded democracy ‘as a right’ and poured contempt on Deng’s half‐measures. Wei was sentenced to 15 years’ imprisonment, fifty other participants were arrested, and the right to use ‘big character’ posters (which Mao had approved) was abolished. Thereafter, however, Deng sought to maintain a balance between the democratic elements within the Party and the conservative veterans. At the same time he supported his protégé Hu Yaobang (Secretary‐General of the CCP from 1980 ), who had gone so far as to affirm (as Chen Erjin had done) that the forms of democracy have universal validity, whatever the content may be in terms of class.

However, when Hu refused to suppress the next great democratic demonstration in 1986 at Kei Da University where the radical democrat Fang Lizhi was Professor of Physics, Deng forced Hu’s dismissal. In early 1989 Hu died. By this time he was the hero of the democratic movement. When the leadership arranged a demeaning low‐key funeral, students marched to Tiananmen Square to protest. Thus the demonstration began.

There were at this point three groups involved in democratic dissent. The first was among intellectuals who hoped for democratization from the top. The second was led by former Red Guards who encouraged democratic revolution from below and were engaged in mobilizing workers and peasants. The third called themselves ‘Neo‐Authoritarians’; they argued that continued authoritarianism was required to carry through economic changes which would create a pluralist society capable of sustaining democracy. In spite of their views, they nevertheless supported the demonstrators.

In 2000 , tapes and transcriptions of the debates within the Secretariat of the Politburo on how to handle the demonstration, drawn from materials to which only the five members of the Secretariat normally had access, were smuggled out to the USA (translated and published in

Tomorrow (February 5th), readers

Tomorrow (February 5th), readers