By Simon Eliot and John Feather

In the 1860s, the introduction of its first named series of education books, the ‘Clarendon Press Series’ (CPS), encouraged Oxford University Press to standardize its payments to authors. Most of them were offered a very generous deal: 50 or 60% of net profits. These payments were made annually and were recorded in the minutes of the Press’ newly-established Finance Committee. The list of payments lengthened every year, as new titles were published and very few were ever allowed to go out of print. Some authors did very well from their association with the Press, but most earned very modest sums. Many of the books in the Clarendon Press Series yielded almost nothing to publisher or author; once we exclude the handful of exceptional cases, typical payments were in the range of £5 to £15 a year.

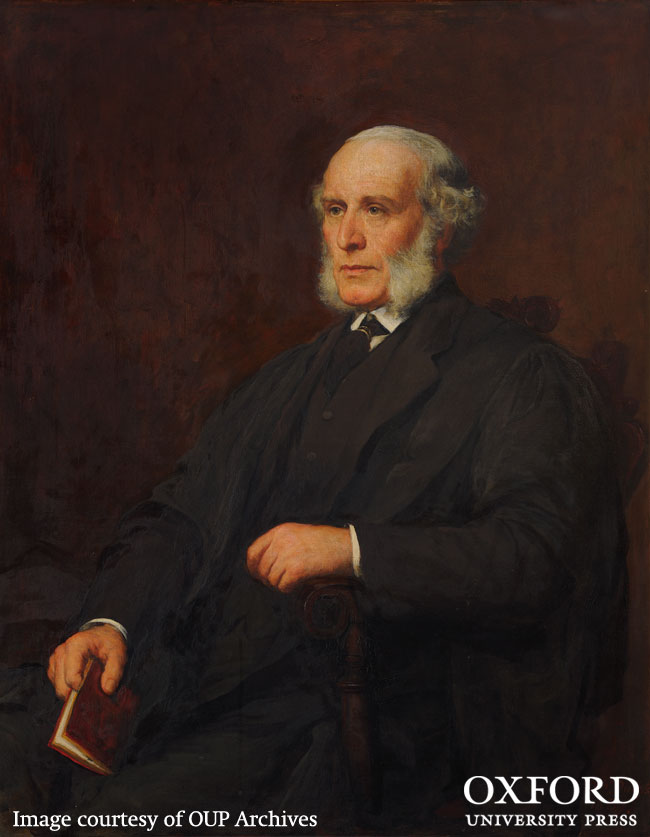

W. Aldis Wright.

The outstanding financial successes of the Clarendon Press Series were the editions of separate plays of Shakespeare intended for school pupils and (increasingly) university students. The first to be published was Macbeth in 1869, but it was the next to appear – Hamlet in 1873 – which became something like a bestseller. In its first year, Hamlet sold 3,380 copies; 20 years and five editions later, 73,140 copies had been accounted for to the editor, W. Aldis Wright (a fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge), who received over the years some £1,400 for this play alone. The whole CPS Shakespeare venture brought Wright an income of about £1,000 a year throughout much of the 1880s. To put this in context, the total of all royalties paid to authors in the late 1880s and early 1890s was about £5000 a year; in some years Wright was taking about 20% of that for his editions of Shakespeare alone.

A broader view of the Press’s payments to its authors on the Learned side can be gained by looking at three sample years: 1875, 1885, and 1895. In November 1875, the Finance Committee minutes listed 99 titles for which authors were being paid annual incomes, the total sum being paid out was £2,216. In November 1885, near the peak of publishing activity in the Clarendon Press Series, the Finance Committee minutes listed 238 titles generating revenue for their authors; they earned £4,740 between them. In November 1895, there were 240 titles leading to payments of £5,076. For most authors, their individual incomes were modest; in 1875, the median income was £7 16s, in 1885 it was £7 18s. However, in 1875 four authors and editors earned more than £100: Liddell and Scott received £372 each (for their Greek Lexicon), Aldis Wright received £220 (for various editions of Shakespeare’s plays), and Bishop Charles Wordsworth £152 (for his Greek Grammar). In 1885, eleven were earning more than £100, including Aldis Wright earning £934, Liddell and Scott each earning £350, Skeat earning £270 (for philological works), and Benjamin Jowett earning £261 (for editions of Plato’s works). In 1895, there were ten, including Aldis Wright with £578, J. B. Allen with £542 (for works on Latin grammar), and Liddell and Scott with £389 each.

These authorial incomes should be set against average academic incomes in Oxford. In the later nineteenth century, although there was much variation, the average annual income for a college fellow would be in the order of £600, usually made up of the fellowship dividend plus the tutorial stipend. In the wake of the Selborne Commission, in the early 1880s a reader would be paid £500, a sum might well be augmented by a fellowship dividend; professorships attracted £900 per annum. It is clear that, although most authors’ incomes were extremely small, the most successful authors, both inside and outside the Clarendon Press Series, were at their height earning a significant addition to their salaries through payments from the Press.

The incomes of the most successful were far in excess of what they would have earned had they sold their copyrights outright. On the other hand, those around the median probably earned less than a lump sum payment would have brought in or, at least, they had to wait longer for it. As a minor compensation to those who were paid small annual sums during this period – though it is unlikely that they would have known it – the purchasing power of the pound was rising between the mid-1860s and the mid-1890s, so their later small payments would have bought them more than their earlier small payments. The pound in a person’s pocket was actually worth more at the end of the nineteenth century than it had been at the beginning.

Simon Eliot is Professor of the History of the Book in the Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London. He is general editor of The History of Oxford University Press, and editor of its Volume II 1780-1896. John Feather, a former President of the Oxford Bibliographical Society, is a Professor at Loughborough University and the author of A History of British Publishing and many other works on the history of books and the book trade. He has contributed to both volumes I and II of The History of Oxford University Press.

With access to extensive archives, The History of Oxford University Press is the first complete scholarly history of the Press, detailing its organization, publications, trade, and international development. Read previous blog posts about the history of Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: William Aldis Wright (1831-1914), editor, Shakespeare Plays, the Clarendon Press Series (Walter William Ouless, 1887). (The Master and Fellows of Trinity College Cambridge) OUP Archives. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post How much could 19th century nonfiction authors earn? appeared first on OUPblog.