By M. Cherif Bassiouni

When Edward Snowden obtained documents as an employee of Booz Allen Hamilton and made them public, the information disclosed was covered by secrecy under US law. That obligation was part of his employment contract, and such disclosure constituted a crime.

He first disclosed this material to Glenn Greenwald of The Guardian in early June of 2013. On 14 June, the Department of Justice filed a complaint against Snowden, charging him with unauthorized disclosure of national defense information under the 1917 Espionage Act, unauthorized disclosure of classified communication intelligence, and theft of government property.

He first disclosed this material to Glenn Greenwald of The Guardian in early June of 2013. On 14 June, the Department of Justice filed a complaint against Snowden, charging him with unauthorized disclosure of national defense information under the 1917 Espionage Act, unauthorized disclosure of classified communication intelligence, and theft of government property.

Snowden made these disclosures while in Hong Kong, and it is reported that the United States sought his extradition pursuant to the treaty it has with Hong Kong, which contains a provision for the exclusion of political offenses. This brings into question the nature of Snowden’s offence.

The Snowden case is inherently simple, and comes down to whether Snowden’s actions were politically motivated or based on social interest. There was no harm to human life, and there was no general social harm. On the contrary, it revealed abuses of secret practices that violate the constitutional right of privacy. Harm to the “national security” is not only subjective but it is also dependent upon who decides what is and what is not part of “national security.”

When it comes to extradition, both the nature of the crime and the motive of the requesting state are taken into account. If the crime for which the person is requested is of a political nature and there is no human or social harm, extradition may be denied on the grounds that it is a purely political offense. This theory is extended to what is called the “relative political offense exception,” when, as incidental to a “purely political offense exception” an unintended social harm results. For example, if someone exercises freedom of speech by speaking loudly in the middle of a square and is charged with disturbing the peace, flees the country, and is sought for extradition, that is a purely political offense exception. If, in the course of fleeing the park they accidentally knock over an aged person who is injured and the state charges him with assault and battery, which would be a relative political offense exception. But the fact that Snowden himself maintains that he did not make public any information that could put intelligence officers in harm’s way, or reveal sources to foreign rivals of the United States means that under extradition law, his case is purely political.

Almost all states allow for the purely political offense exception to apply. Those that do not, bypass the exception for political reasons. This explains why Snowden went to Russia, though the UK would have found it difficult to extradite him too. It helps to look back to the case of Julian Assange, who was sought by the United States when in the UK. When the UK could not extradite Assange because of the purely political offense exception doctrine, the United States had Sweden seek his extradition from the UK for what was a criminal investigation into a common crime (sexual assault). This is what led Assange to seek refuge in the Ecuadorian embassy.

The fact that the purely political offence exception doctrine arose with respect to the Snowden case, assuming it would be the subject of extradition proceedings, is curious to say the least. Would a government official of, say, the Comoros Islands be the subject of similar international attention for the disclosure of some secret skullduggery that the government had classified as top secret? The answer is of course no. What makes this case a cause célèbre is that it has to do with the United States, because it embarrasses the United States, and because it reveals that the government of the United States and at least one of its most important agencies (the NSA) has engaged in violations of the Constitution and laws on the protection of individual privacy. It has shown abuses of the powers by the executive branch to obtain information from private sector companies, which would not be otherwise obtainable without a proper court order. This of course is what makes the Snowden case so extraordinary since it is about a US citizen doing what he believed was right to better serve his country and whose very government was violating its constitution and laws.

M. Cherif Bassiouni is Emeritus Professor of Law at DePaul University where he taught from 1964-2012, where he was a founding member of the International Human Rights Law Institute (established in 1990), and served as President from 1990-2007, and then President Emeritus. He is also President, International Institute of Higher Studies in Criminal Sciences, Siracusa, Italy since 1989. He is the author of International Extradition: United States Law and Practice, Sixth Edition.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

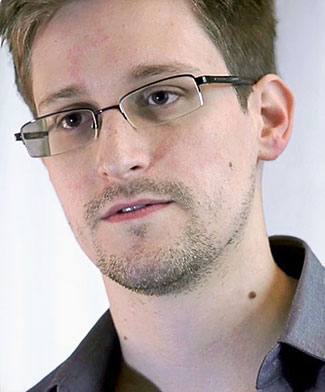

Image: Screenshot of Edward Snowden by Laura Poitras/Praxis Films. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post For social good, for political interest: the case of Edward Snowden appeared first on OUPblog.

It's good that while teaching the Jewish kids you felt the need to explain to them how they should feel if they happen to be called k***s by a stranger, and that you equate your authority over the classroom to the situation between the class and African Americans ... It's not that using these words don't make for powerful teaching tools -- they do -- but you dictating the emotions and experiences between races and ethnicities seems pretty offensive.

Way to bravely enter into the spirit of the post, "Anonymous". You raise a valid point, but is there no other way it could have been raised?

Good post, Matthew. Though I think it's clear that "slave" doesn't make the novel better. (It's been many years since I read it, but is "slave" even always an adequate replacement in terms of the facts of the novel?)

It doesn't sound like dictating to me, but much more like asking students to consider and question their own responses.

Anonymous is giving a pretty uncharitable reading of this post. And being cowardly to boot. JeffV

To replace "nigger" with "slave" does at least two things counter to Twain's apparent intentions. First, the novel is notable for its use of vernacular, so much so that it can take a little while to understand what characters are actually saying; in the new version this key aspect of the vernacular is removed. Second, the textual change diminishes the level of character change that occurs with Huck during the river journey. This is one of those great books that can bring me to tears when Huck decides that he would rather go to Hell than to sell out Jim. While I'm glad that there is a desire to still teach the novel in schools, it saddens to me that it is done at the expense of a valid discussion of racism then and now. I hope that other instructors, like you, will use the original version as the spark to address these complex issues.

--Eric S.