By Sarah Dry

Nearly three hundred years since his death, Isaac Newton is as much a myth as a man. The mythical Newton abounds in contradictions; he is a semi-divine genius and a mad alchemist, a somber and solitary thinker and a passionate religious heretic. Myths usually have an element of truth to them but how many Newtonian varieties are true? Here are ten of the most common, debunked or confirmed by the evidence of his own private papers, kept hidden for centuries and now freely available online.

10. Newton was a heretic who had to keep his religious beliefs secret.

True. While Newton regularly attended chapel, he abstained from taking holy orders at Trinity College. No official excuse survives, but numerous theological treatises he left make perfectly clear why he refused to become an ordained clergyman, as College fellows were normally obliged to do. Newton believed that the doctrine of the Trinity, in which the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost were given equal status, was the result of centuries of corruption of the original Christian message and therefore false. Trinity College’s most famous fellow was, in fact, an anti-Trinitarian.

9. Newton never laughed.

False, but only just. There are only two specific instances that we know of when the great man laughed. One was when a friend to whom he had lent a volume of Euclid’s Elements asked what the point of it was, ‘upon which Sir Isaac was very merry.’ (The point being that if you have to ask what the point of Euclid is, you have already missed it.) So far, so moderately funny. The second time Newton laughed was during a conversation about his theory that comets inevitably crash into the stars around which they orbit. Newton noted that this applied not just to other stars but to the Sun as well and laughed while remarking to his interlocutor John Conduitt ‘that concerns us more.’

8. Newton was an alchemist.

True. Alchemical manuscripts make up roughly one tenth of the ten million words of private writing that Newton left on his death. This archive contains very few original treatises by Newton himself, but what does remain tells us in minute detail how he assessed the credibility of mysterious authors and their work. Most are copies of other people’s writings, along with recipes, a long alchemical index and laboratory notebooks. This material puzzled and disappointed many who encountered it, such as biographer David Brewster, who lamented ‘how a mind of such power, and so nobly occupied with the abstractions of geometry, and the study of the material world, could stoop to be even the copyist of the most contemptible alchemical work, the obvious production of a fool and a knave.’ While Brewster tried to sweep Newton’s alchemy under the rug, John Maynard Keynes made a splash when he wrote provocatively that Newton was the ‘last of the magicians’ rather than the ‘first king of reason.’

7. Newton believed that life on earth (and most likely on other planets in the universe) was sustained by dust and other vital particles from the tails of comets.

True. In Book 3 of the Principia, Newton wrote extensively how the rarefied vapour in comet’s tails was eventually drawn to earth by gravity, where it was required for the ‘conservation of the sea, and fluids of the planets’ and was most likely responsible for the ‘spirit’ which makes up the ‘most subtle and useful part of our air, and so much required to sustain the life of all things with us.’

6. Newton was a self-taught genius who made his pivotal discoveries in mathematics, physics and optics alone in his childhood home of Woolsthorpe while waiting out the plague years of 1665-7.

False, though this is a tricky one. One of the main treasures that scholars have sought in Newton’s papers is evidence for his scientific genius and for the method he used to make his discoveries. It is true that Newton’s intellectual achievement dwarfed that of his contemporaries. It is also true that as a 23 year-old, Newton made stunning progress on the calculus, and on his theories of gravity and light while on a plague-induced hiatus from his undergraduate studies at Trinity College. Evidence for these discoveries exists in notebooks which he saved for the rest of his life. However, notebooks kept at roughly the same time, both during his student days and his so called annus mirabilis, also demonstrate that Newton read and took careful notes on the work of leading mathematicians and natural philosophers, and that many of his signature discoveries owe much to them.

5. Newton found secret numerological codes in the Bible.

True. Like his fellow analysts of scripture, Newton believed there were important meanings attached to the numbers found there. In one theological treatise, Newton argues that the Pope is the anti-Christ based in part on the appearance in Scripture of the number of the name of the beast, 666. In another, he expounds on the meaning of the number 7, which figures prominently in the numbers of trumpets, vials and thunders found in Revelation.

4. Newton had terrible handwriting, like all geniuses.

False. Newton’s handwriting is usually clear and easy to read. It did change somewhat throughout his life. His youthful handwriting is slightly more angular, while in his old age, he wrote in a more open and rounded hand. More challenging than deciphering his handwriting is making sense of Newton’s heavily worked-over drafts, which are crowded with deletions and additions. He also left plenty of very neat drafts, especially of his work on church history and doctrine, which some considered to be suspiciously clean, evidence, said his 19th century cataloguers, of Newton’s having fallen in love with his own hand-writing.

3. Newton believed the earth was created in seven days.

True. Newton believed that the Earth was created in seven days, but he assumed that the duration of one revolution of the planet at the beginning of time was much slower than it is today.

2. Newton discovered universal gravitation after seeing an apple fall from a tree.

False, though Newton himself was partly responsible for this myth. Seeking to shore up his legacy at the end of his life, Newton told several people, including Voltaire and his friend William Stukeley, the story of how he had observed an apple falling from a tree while waiting out the plague in Woolsthorpe between 1665-7. (He never said it hit him on the head.) At that time Newton was struck by two key ideas—that apples fall straight to the center of the earth with no deviation and that the attractive power of the earth extends beyond the upper atmosphere. As important as they are, these insights were not sufficient to get Newton to universal gravitation. That final, stunning leap came some twenty years later, in 1685, after Edmund Halley asked Newton if he could calculate the forces responsible for an elliptical planetary orbit.

1. Newton was a virgin.

Almost certainly true. One bit of evidence comes via Voltaire, who heard it from Newton’s physician Richard Mead and wrote it up in his Letters on England, noting that unlike Descartes, Newton was ‘never sensible to any passion, was not subject to the common frailties of mankind, nor ever had any commerce with women.’ More substantively, there is Newton’s lifelong status as a self-proclaimed godly bachelor who berated his friend Locke for trying to ‘embroil’ him with women and who wrote passionately about how other godly men struggled to tame their lust.

Sarah Dry is a writer, independent scholar, and a former post-doctoral fellow at the London School of Economics. She is the author of The Newton Papers: The Strange and True Odyssey of Isaac Newton’s Manuscripts. She blogs at sarahdry.wordpress.com and tweets at @SarahDry1.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

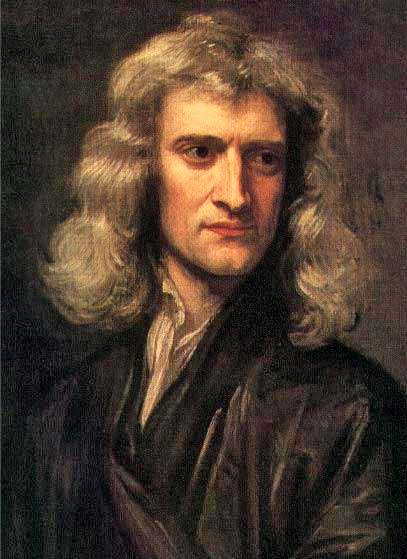

Image credit: Portrait of Isaac Newton by Sir Godfrey Kneller. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post True or false? Ten myths about Isaac Newton appeared first on OUPblog.