By Qiliang Ding and Ya Hu

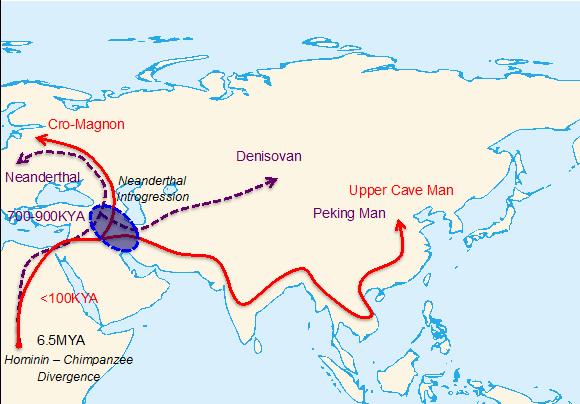

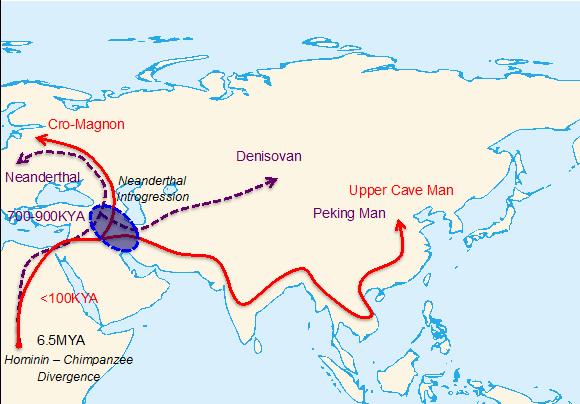

Hominins and their closest living relative, chimpanzees, diverged approximately 6.5 million years ago on African continent. Fossil evidence suggests hominins have migrated away from Africa at least twice since then. Crania of the first wave of migrants, such as Neanderthals in Europe and Peking Man in East Asia, show distinct morphological features that are different from contemporary humans (also known as Homo sapiens sapiens). The first wave of migration was estimated to have occurred 7-9,000,000 years ago. In the 1990s, studies on Y-chromosome and mitochondrial DNA proved that the contemporary Eurasians are descendants of the second wave of migrants, who migrated out of Africa less than 100,000 years ago.

It has been reported that the habitats of Neanderthals and ancestors of contemporary Eurasians overlapped both in time and space, and therefore provides possibility of introgression between Neanderthals and ancestors of Eurasians. This possibility is confirmed by recent studies, which suggest that about 1-4% of Eurasian genomes are from Neanderthal introgression.

Adaptation to local environment is crucial for newly-arrived migrants, and the process of local adaptation is sometimes time-consuming. Since Neanderthals arrived in Eurasia ten times earlier than ancestors of Eurasians, we are trying to figure out whether the Neanderthal introgressions helped the ancestors of Eurasians adapt to the local environment.

Two major out-of-Africa migration waves of hominins. The purple and red colors represent the first and second migration waves, respectively. The circle near Middle East represents a possible location where main Neanderthal introgression might have occurred.

Our study reports that Neanderthal introgressive segments on chromosome 3 may have helped East Asians adapting to the intensity of ultraviolet-B (UV-B) irradiation in sunlight. We call the region containing the Neanderthal introgression the “HYAL” region, as it contains three genes that encode hyaluronoglucosaminidases.

We first noticed that the entire HYAL region is included in an unusually large linkage disequilibrium (LD) block in East Asian populations. Such a large LD block is a typical signature of positive natural selection. More interestingly, it is observed that some Eurasian haplotypes at the HYAL region show a closer relationship to the Neanderthal haplotype than to the contemporary African haplotypes, implicating recent Neanderthal introgression. We confirmed the Neanderthal introgression in HYAL region by employing a series of statistical and population genetic analyses.

Further, we examined whether the HYAL region was under positive natural selection using two published statistical tests. Both suggest that the HYAL region was under positive natural selection, and pinpoint a set of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) contributed by Neanderthal introgression as the candidate targets of positive natural selection.

We then explored the potential functional importance of Neanderthal introgression in the HYAL region. The HYAL genes attracted our attention, as they are important in hyaluronan metabolism and cellular response to UV-B irradiation. We noticed that an SNP pinpointed as a potential target for positive natural selection was located in the most conservative exon of HYAL2 gene. We suspect that this SNP (known as rs35455589) may have altered the function of HYAL2 protein, since this SNP is also associated with the risk of keloid, a dermatological disorder related to hyaluronan metabolism.

Next, we interrogated the global distribution of Neanderthal introgression at the HYAL region. It is observed that the Neanderthal introgression reaches a very high frequency in East Asian populations, which ranges from 49.4% in Japanese to 66.5% in Southern Han Chinese. The frequency of Neanderthal introgression is higher in southern East Asian populations compared to northern East Asian populations. Such evidence might suggest latitude-dependent selection, which implicates the role of UV-B intensity.

We discovered that Neanderthal introgression on chromosome 3 was under positive natural selection in East Asians. We also found that a gene (HYAL2) in the introgressive region is related to the cellular response to UV-B, and an allele from Neanderthal introgression may have altered the function of HYAL2. As such, we think it is possible that Neanderthals may have helped East Asians to adapt to sunlight.

Qiliang Ding and Ya Hu are MSc Students at the Institute of Genetics at Fudan University and Intern Students at the CAS-MPG Partner Institute of Computational Biology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Their research interest lies in revealing evolutionary history of hominids using ancient and contemporary human genomes. They are the authors of the paper “Neanderthal Introgression at Chromosome 3p21.31 Was Under Positive Natural Selection in East Asians,” which appears in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution.

Molecular Biology and Evolution publishes research at the interface of molecular (including genomics) and evolutionary biology.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only earth, environmental, and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Background map via Wikimedia Commons, with annotations by the authors.

The post Neanderthals may have helped East Asians adapting to sunlight appeared first on OUPblog.

By Thomas Wynn and Frederick L. Coolidge

Neandertal communication must have been different from modern language. To repeat a point made often in this book, Neandertals were not a stage of evolution that preceded modern humans. They were a distinct population that had a separate evolutionary history for several hundred thousand years, during which time they evolved a number of derived characteristics not shared with Homo sapiens sapiens. At the same time, a continent away, our ancestors were evolving as well. Undoubtedly both Neandertals and Homo sapiens sapiens continued to share many characteristics that each retained from their common ancestor, including characteristics of communication. To put it another way, the only features that we can confidently assign to both Neandertals and Homo sapiens sapiens are features inherited from Homo heidelbergensis. If Homo heidelbergensis communicated via modern style words and modern syntax, then we can safely attribute these to Neandertals as well. Most scholars find this highly unlikely, largely because Homo heidelbergensis brains were slightly smaller than ours and smaller than Neandertals’, but also because the archaeological record of Homo heidelbergensis is much less ‘modern’ than either ours or Neandertals’. Thus, we must conclude that Neandertal communication had evolved along its own path, and that this path may have been quite different from the one followed by our ancestors. The result must have been a difference far greater than the difference between Chinese and English, or indeed between any pair of human languages. Specifying just how Neandertal communication differed from ours may be impossible, at least at our current level of understanding. But we can attempt to set out general features of Neandertal communication based on what we know from the comparative, fossil, and archaeological records.

As we have tried to show in previous chapters, the paleoanthropological record of Neandertals suggests that they relied heavily on two styles of thinking – expert cognition and embodied social cognition. These, at least, are the cognitive styles that best encompass what we know of Neandertal daily life. And they do carry implications for communication. Neandertals were expert stone knappers, relied on detailed knowledge of landscape, and a large body of hunting tactics. It is possible that all of this knowledge existed as alinguistic motor procedures learned through observation, failure, and repetition. We just think it unlikely. If an experienced knapper could focus the attention of a novice using words it would be easier to learn Levallois. Even more useful would be labels for features of the landscape, and perhaps even routes, enabling Neandertal hunters to refer to any location in their territories. Such labels would almost have been required if widely dispersed foraging groups needed to congregate at certain places (e.g., La Cotte). And most critical of all, in a natural selection sense, would be an ability to indicate a hunting tactic prior to execution. These labels must have been words of some kind. We suspect that Neandertal words were always embedded in a rich social and environmental context that included gesturing (e.g., pointing) and emotionally laden tones of voice, much as most human vocal communication is similarly embedded, a feature of communication probably inherited from Homo heidelbergensis.

At the risk of crawling even further out on a limb than the two of us usually go, we make the following suggestions about Neandertal communication:

1) Neandertals had speech. Their expanded Broca’s area in the brain, and their possession of a human FOXP2 gene both suggest this. Neandertal speech was probably based on a large (perhaps huge) vocabulary – words for places, routes, techniques, individuals, and emotions. We have shown that Neandertal expertise was large

By John Reader

A blaze of media attention recently greeted the claim that a newly discovered hominid species, , marked the transition between an older ape-like ancestor, such as Australopithecus afarensis, and a more recent representative of the human line, Homo erectus. As well as extensive TV, radio and front-page coverage, the fossils found by Lee Berger and his team at a site near Pretoria in South Africa featured prominently in National Geographic, with an illustration of the three species striding manfully across the page. In the middle, Au. sediba was marked with twelve points of similarity: six linking it to Au. afarensis on the left and six to H. erectus on the right. Though Berger did not explicitly describe Au. sediba as a link between the two species, the inference was clear and not discouraged. The Missing Link was in the news again.

By Purdy, Director of Publicity

We are already half way to May and it just dawned on me that April is National Poetry Month. Last year you may remember the OUP blog featured the Buffalo Poets (an unruly band of anarchists and beer swillin’ poets, i.e. friends of mine). and while I adore the Buffalo Poets and their continuing mission to bring poetry to the masses with their NYC area readings, I have decided it might be nice to hear from another one of my poet friends who has a completely different style of writing this year. Michael Manner and I were English majors in a state school in Upstate NY before the days of email, before the days of the fax. Indeed, the modern technology of the time was floppy disk computers, and the CD was quickly replacing the cassette tape.

Manner and I have kept in touch through the years and when we are together we often argue and bicker like a married couple about love, fear, greed, envy, lust, hypocrisy, music, cats v. dogs, words et al. I think the only thing we ever seem to agree on is that chocolate milk is the greatest invention ever. But enough about me, Manner is a freelance computer consultant living with his mangy, blind cat in Williamsburg Brooklyn, NY. His love of poetry dates back to when dinosaurs roamed the earth and he first heard the words “ugga bugga” uttered by a passing Neanderthal woman. He’s been writing verse since the Iron Age and one day hopes to be cited in the OED. His fave comic book hero is Batman. Despite all this I think is is a truly talented poet and have asked him to post some poems on this blog. You be his judge.

Lust

It seminates from the chill of dawn.

Cast from bell buoy to shore

Through an otherwise silent fog.

Boil, Breach and Boom

Between the fetch and shiver.

We pant in the swell

And melt into sand and spume.

Candle-bloom dusk coils into night.

Settling into tranquil certainty, drifting

in the after flash –

when clouds hide in November and

raindrops fall like parachutes.

This immortal lightning –

only a plangent echo.

This reprieve from decay only hollow.

ShareThis

Afyon, Turkey

Coordinates: 38 45 N 30 33 E

Elevation: 3,392 feet (1,034 m)

When speaking of edible plants (and their medicinal properties), the opium poppy tends to get a bad rap. Most likely this is because while its harmless leaves, oil, paste, and ripened seeds can be found in various Turkish, Arabian, and Persian dishes, the narcotic properties of unripe poppy seeds have made it a lucrative black market crop in recent decades. (more…)

Share This