For my birthday my husband picked me up a copy of the bestselling book NurtureShock by Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman. To be frank, I hadn’t heard of it. Though its been called “The Freakonomics of child rearing” and lauded by reviewer after reviewer it’s from the world of adult books. I traipse there but rarely. Still, I’m great with child (ten days away from the due date, in fact) and this promised to be a fascinating read. Covering everything from the detrimental effects that come with telling a kid that they’re smart to aggression in the home I settled down and devoured it with pleasure. In doing so, one chapter in particular caught my eye. Chapter Three: “Why White Parents Don’t Talk About Race: Does teaching children about race and skin color make them better of or worse?”

For my birthday my husband picked me up a copy of the bestselling book NurtureShock by Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman. To be frank, I hadn’t heard of it. Though its been called “The Freakonomics of child rearing” and lauded by reviewer after reviewer it’s from the world of adult books. I traipse there but rarely. Still, I’m great with child (ten days away from the due date, in fact) and this promised to be a fascinating read. Covering everything from the detrimental effects that come with telling a kid that they’re smart to aggression in the home I settled down and devoured it with pleasure. In doing so, one chapter in particular caught my eye. Chapter Three: “Why White Parents Don’t Talk About Race: Does teaching children about race and skin color make them better of or worse?”

Culling several studies together, the book makes the point that while, “Nonwhite parents are about three times more likely to discuss race than white parents; 75% of the latter never, or almost never, talk about race.” Studies that required that parents do so with their young children saw white parent after white parent balk at the idea. There’s this notion out there that children are little innocents and that pointing out race will somehow taint their race blind worldview. Turns out, nothing could be further from the truth. Anyone who has ever had a kid will know that they like to categorize themselves and their friends into groups. Race is the easiest way to do so, so from a very early age the children will be prone to “in-group favoritism”.

I thought this through. My kiddo attends a daycare here in Harlem. In her Preschool A class she is only one of two children who are not African-American or of mixed race. It’s a great place and certainly it assuages my white guilt, having my kid in such a diverse environment. But according to NurtureShock it isn’t enough to just plop your child in what you assume will be a color-blind environment. As the book says, “We might imagine we’re creating color-blind environments for children, but differences in skin color or hair or weight are like differences in gender – they’re plainly visible.”

And as I read this I realized that I myself have done the exact same balking at race references as mentioned in the book. I’ve an amazing personal of library of diverse children’s books accumulated through my job and the donations of friends and family members alike from over the years. My job in giving my child a sense of diversity and multiculturalism is therefore done, right? Not so much. Take the case of Busing Brewster by Rich Michelson. This is a book that years ago appeared on the New York Times Best Illustrated list (whose committee, full disclosure, I served on). It’s an older picture book, and one that I’d probably recommend for the 4-7-year-old crowd. Still, it’s a picture book so one day the small Bird picked it up and asked to be read it. She is, I should point out, two-years-old. And as I read it to her, I found myself softening the harsh elements. If you’re unfamiliar with it, in this book two boys are integrated into a new school in the 1960s. In doing so they face outright racism varying from yelling protestors to bricks thrown through their school bus windows. Was my two-year-old ready for this? I figured probably not, but watching myself edit the book for her level turned out to be a strange pastime. I wasn’t just editing out the hatred but was also failing to explain why the kids were moving to a new school at all. It was as if I was afraid that mentioning race to her would cause her to say embarrassing things at daycare the next day, something I wanted desperately to avoid. An understandable reaction, but the right one? I’m not sure about that at all.

Going back to the book, the more I read the more I realized that if we want parents to have serious discussions about race with their four and five and six-year-olds then we need to have books that help to do this. So as I read I kept a particular eye out for moments when the authors would mention using literature with kids to drill home various points. Though they never come out and say that children’s books can be useful in this regard, there are several incidents recounted that name check various books. One such title is Twas the Night B’Fore Christmas: An African-American Version by Melodye Benson Rosales. Originally published in 1996 the title was criticized for its use of colloquial language. As the Horn Book Guide said at the time, “Painful dialect (‘The stockin’s was laid / by the chimney wit’ care, / For the chil’ren hoped Santy Claus / soon would be there’) and garish illustrations make this ‘African-American version’ seem more like an unintentional parody of Clement Moore’s 1822 poem. So why isn’t anybody laughing?” In NurtureShock the book was used to combat children’s stereotypes of whether or not Santa was black or white. For the same thing, one would probably turn these days to the Rachel Isadora version instead. Disappointingly the only other time literature is mentioned is when a study is recounted where kids read historical biographies of Jackie Robinson. Still, one gathers that these were not from books but rather textbooks or printed bios made specifically for the study.

What we can take away from this are the ages at which kids need to learn about race. At one moment a study was conducted between first graders and third graders. At the end we read, “The researchers found this worked wonders on the first-grade children. Having been in the cross-race study groups led to significantly more cross-race play. But it made no difference on the third-grade children. It’s possible that by third grade, when parents usually recognize it’s safe to start talking a little about race, the developmental window has already closed.”

With that in mind, I decided I needed to find a booklist that would best help parents frame a discussion of race or other cultural factors with their younger children. Which was about the time I realized that finding such a list was incredibly difficult. I’m not saying it doesn’t exist. I’m sure there must be some out there. I just couldn’t figure out where they were hiding. Even lists like SLJ’s recent Culturally Diverse Books list and subsequent Expanded Cultural Diversity booklist place the bulk of importance on books for older children. Books for younger kids almost never mention race specifically in any context.

So I decided to do what librarians do when they can’t find the resources they need. I made a book list that people could use to discuss difficult subjects with younger kids. And to my amazement, it was incredibly hard to create. Not too long ago I had written a post about Casual Diversity in children’s literature. Well, apparently Casual Diversity is a very easy concept to put in a book for kids. In fact, as I’ve gone through list after list of diverse works of children’s literature, what I keep finding is that the tendency is towards just making a character one race or another without discussing what that means (a criticism of “casual diversity” that cropped up at the time of the post itself).

In constructing this list I also tried like the devil to include books that could be used to discuss their individual issues without lapsing into painful didacticism. No mean feat. For the most part, books about race or religion or alternative lifestyles will either make the situation seem completely normal (which is good, and which we also need) or they’ll slap some sappy “message” all over the puppy making it essentially useless as a piece of literature.

The final result is below. If I were to say the ages this was for I’d go with 4-8 or so. I figured it didn’t make sense to necessarily limit it to race, since discussions of race and alternative lifestyles would also apply. NurtureShock includes the fascinating fact that a lot of white parents feel perfectly comfortable drilling home the fact that boys and girls are equal, while ignoring the issues of race entirely. So I’ve eschewed gender equality books (which are fairly prevalent anyway) and limited this to other “differences” a kiddo might pick up on. If you have titles you’d add to this, do let me know what they are.

A Picture Book Reading List for Discussing Race, Religion, and Alternative Lifestyles with the Young

She Sang Promise: The Story of Betty Mae Jumper, Seminole Tribal Leader by Jan Godown Annino, illustrated by Lisa Desimini – Finding picture books about Native Americans is hard to begin with. Now try finding some that actually discuss the prejudices and lives they’ve lead. I looked through Debbie Reese’s recent list of Resources and Kid Lit About American Indians but was unable to find much of anything for young ages that could discuss the prejudice faced by Native American children (or their trials historically) for the picture book set. Insofar as I can tell, you have to turn to real world history to get anywhere near that subject. With that in mind, I decided to go with Annino’s amazing bio of the too little known Betty Mae Jumper, the first female Seminole Tribal Leader. In the course of this story kids learn about the prejudices not just facing the Seminoles historically but also within their own tribe and towards women nationally. There are just loads of jumping off discussion points to be plumbed here.

The Soccer Fence: A Story of Friendship, Hope, and Apartheid in South Africa by Phil Bildner, ill. Jesse Joshua Watson – Picture books that deal with historical racism tend to be preferred by teachers, and there are reasons for that. In NurtureShock the study where kids were given different texts on Jackie Robinson ends with this rather fascinating selection: “She notes the bios were explicit, but about historical discrimination. ‘If we’d had them read stories of contemporary discrimination from today’s newspapers, it’s quite possible it would have made the whites defensive, and only made the blacks angry at the whites’.” Hm. Well, certainly finding contemporary picture books about racism towards African-Americans is remarkably difficult. Sometimes authors find that even setting the books in America can be hard. Sure you have books like A Taste of Colored Water from time to time (which I have included on this list), but anything recent is eschewed. So for authors that want to include more recent kids, South Africa has proven ripe for books like Bildner’s here. Initially this book reminded me of the well meaning but ultimately flawed Desmond and the Very Mean Word: A Story of Forgiveness by Desmond Tutu. Tutu’s book, however, simplified the issue of race to a watered down non-point. As NurtureShock says, lots of parents use vague terms like “Everybody’s equal” or “God made all of us” or “Under the skin, we’re all the same” to talk about race. That’s what Tutu’s book did, even when telling the story of white and black characters. Bildner’s book isn’t perfect and it verges on the idealistic in terms of different races coming together, but after a couple rereads I came to the decision that ultimately it’s a mighty useful tool.

A Taste of Colored Water by Matt Faulkner – I remember when this book first came out. It got starred reviews from places like Kirkus but I wasn’t particularly interested in it. The premise, as you might be able to tell from the cover, involved two kids who heard the term “colored water” and misinterpreted it literally. Faulkner (who currently has the graphic novel Gaijin: American Prisoner of War about a mixed-race kid in an internment camp out on shelves) isn’t the kind of author afraid of shying away from a difficult subject. In many ways this remains his best known work.

Be Good to Eddie Lee by Virginia M. Fleming – I dare you to find me a book more recent than this 1997 title that discusses Down Syndrome in such a straightforward context. Books that discuss kids and disabilities are few and far between. It got great reviews when it first came out (and Floyd Cooper did the art!). It also has the guts to have a character who says things like, “God didn’t make mistakes, and Eddie Lee was a mistake if there ever was one.” Recently publishers have been doing better when it comes to books about autism, but it’s almost as if they think we can only handle one disability at a time. Publish books on more than one issue? Insanity! Only Albert Whitman Books really tries to do quality issues but even they haven’t touched on Down Syndrome. It’s almost as if it was a big issue in the 80s and 90s and then disappeared from the public conversation. Now it’s all peanut allergies and ADD.

Layla’s Head Scarf by Miriam Cohen, illustrated by Ronald Himler – We get close to didactic here without ever quite tipping over. Finding good books about contemporary Muslim kids isn’t impossible, but it certainly isn’t easy to do. And books that actually talk about what people wear in school? Rarities. This one was very young and did a good job (though, alas, it referred to the head scarf as simply a head scarf and not by the proper term “hijab”).

10,000 Dresses by Marcus Ewert, illustrated by Rex Ray – As it turns out, finding a book about gay parents that actually discusses the issue does not exist. Or maybe it does and I just missed it entirely. Instead, what I was able to find were a couple books about boys that wear girls’ clothing. Long before that atrocious My Princess Boy hit the shelves, Ewert wrote a book where a boy honest-to-goodness identified as a girl. This is, to the best of my knowledge, the only book I’ve encountered to go the distance in that respect AND it had a story above and beyond its message.

Jacob’s New Dress by Sarah and Ian Hoffman, illustrated by Chris Case – And this is the most recent boys-in-dresses book (though the art of Morris Micklewhite and the Tangerine Dress is quite lovely as well, so check out the Seven Impossible Things posting on Gender-Nonconforming Picture Books if you get a chance). What I really like about this book, though, is how instructional it is to parents. When Jacob specifies his preferences for dresses his mother and father definitely have to pause and think about how to handle the information but their responses are really quite grand. Jacob doesn’t identify as a girl, but his desire to wear dresses makes him stand out. No doubt.

Big Red Lollipop by Rukhsana Khan, illustrated by Sophie Blackall – As I mentioned before, Muslim kids in picture books are few and far between. And for the most part this book is just an example of Casual Diversity rather than any overt lessons. But skillful parents and teachers could certainly place the book’s story in context. Talking about immigrants to America and how there are different rules and mores in one country vs. another. Plus it’s one of my very favorite books of all time and any excuse to post it is good enough for me.

Goin’ Someplace Special by Patricia McKissack, illustrated by Jerry Pinkney – To be honest, there are a fair number of historical picture books like this one that discuss historical racism. I figured I’d put a couple on this list, but one the best may well be McKissack’s here. Here we have a kid who actually faces racism firsthand. There’s a reason schools assign this one every single summer for summer reading. As the Kirkus review put it, “Every plot element contributes to the theme, leaving McKissack’s autobiographical work open to charges of didacticism. But no one can argue with its main themes: segregation is bad, learning and libraries are good.”

Busing Brewster by Rich Michelson, illustrated by R.G. Roth – Part of what I like so much about this book is that it’s not just a case of discussing racial differences. The book’s concentration on busing and integration is an essential part of American history that simply cannot be ignored. Add in the fact that the white bully in the book is seen getting essentially indoctrinated into his particular brand of racism by his father, and you’ve a darn good book on a difficult subject. As I mentioned before, reading it to my two-year-old proved difficult, but at the very least I should have given it some historical context. Next time.

First Day in Grapes by L. King Perez, illustrated by Robert Casilla – I ran into the same problem with Latino characters that I found with Native Americans. Unless we’re talking about specific historical people who faced challenges, books with Latinos often eschew controversial aspects. This was one of the very few I could find that talks about contemporary migrant kids. There are a couple others (Armando and the Blue Tarp School by Edith Hope Fine and Judith Pinkerton Josephson comes to mind) but I think I liked this one best. The didacticism is low-key and the storyline doesn’t exist solely to support the message. That Pura Belpre Honor on the cover ain’t there for nothing.

The Favorite Daughter by Allen Say – I’m listing these books alphabetically by author but if I were to list them in terms of importance then I might have considered making this one of the first on the list. I did think about adding My Name Is Yoon by Helen Recorvits and/or The Name Jar by Yangsook Choi to this list but Say’s book is just so much gutsier in so many ways. Yuriko gets teased in school about her name and hair (she’s blond with Asian features) and faces other examples of prejudice. Her response is to change her name to “Michelle”, a move that gives her father reason to guide her back to her roots, so to speak. It’s a book done almost entirely in dialogue (rare in and of itself) and so smart. You could also add Cleversticks by Bernard Ashley or Yoko by Rosemary Wells to this list of titles too, by the way.

The Sneetches and Other Stories by Dr. Seuss – Well, why not? Seuss was the lesson man back before it was cool. And when I mentioned this post to my husband he pointed out that when we were in school, The Sneetches was the gold standard for talking about prejudice and race. Sure it’s a great big green starred metaphor, but if we feel like it no longer has a place in our schools then we’re just not paying attention.

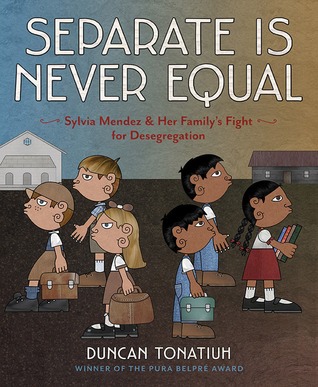

Separate Is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez & Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation by Duncan Tonatiuh – I first heard Sylvia’s story last year when I reviewed When Thunder Comes: Poems for Civil Rights Leaders by J. Patrick Lewis. As I mentioned before, Latino fictional stories are tricky. Historical notes are rare, though, and this story is absolutely beautifully done. The discussion isn’t just of race but shows how skin color really affected people’s prejudices during this time.

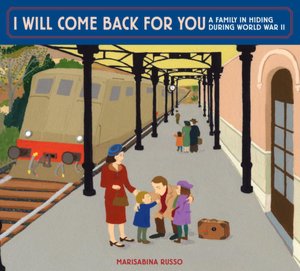

I Will Come Back for You by Marisabina Russo – Well, if we’re talking about race then are we also talking about the Holocaust? It’s a legitimate question. Marjorie Ingall recently wrote a very smart piece for Tablet Magazine about whether or not young children need to learn about the Holocaust where she name checked this book. Her post ties in beautifully with the NurtureShock chapter, in that she points out that if you do not provide the lesson for your kids they’re just going to pick it up somewhere else in a form you probably don’t approve of. This book puts you in the kids’ shoes (and NOT in a concentration camp). Just good for opening discussions.

Definitely there are books that could fit on this list. So list ‘em!

Just did a long comment that is “awaiting moderation” probably because it is long. At the end of it I pointed to my post in response to yours: Very glad you brought this up although I’m not sure I agree with you. I just did the following post giving some of my own musings on this: http://medinger.wordpress.com/2014/05/12/talking-diversity-with-young-children/

Let’s see if this one goes through!

One from our school library shelves that I’d add to this list is WHEN I WAS EIGHT by Christy Jordan-Fenton and Margaret Pokiak-Fenton, illustrated by Gabrielle Grimard. The story is based on Margaret Pokiak-Fenton’s experience of leaving her native Inuit village to attend a Catholic boarding school so she could learn to read. This one made me cringe when I first read it–it’s weighty subject matter for a picture book billed for kids in grades K-4. But if you want to talk about the pain of discrimination, this one should be included in every library’s collection. The sequel is called NOT MY GIRL, which deals with Margaret returning home two years after attending the “outsiders’” school and the culture shock she experiences in her native home.

I like that these books have versions of the same story for older kids (FATTY LEGS and A STRANGER AT HOME). For older readers who find these books, I’d also hand them MY NAME IS NOT EASY by Debby Dahl Edwardson.

Good morning! My doctorate is in early childhood education. Then and now, I read a lot of the research literature about race and how children process it. I read a lot about racism, and, when my daughter was little, had awkward conversations with the ‘color blind’ parent many times. In a nutshell, we (as a society) tend not to talk about bad things.

But let me back up to say this: A key piece to remember is who the ‘we’ is in what we read and say and do. The default is white. We generally means white. Generally, it is white parents who want to teach their children to be ‘color blind’ and who want to avoid discussing anything difficult about race. For a great many not-white families, it cannot be avoided. Racism is a fact of our daily lives. Being Native was/is part of our daily lives. Implicitly and explicitly, Liz learned about what it meant to be Native and she was proud of it. Seeing her heritage as someone else’s costume or plaything was not something I could ignore. I had to give her words to understand what she was seeing. I wrote about that in an article for HORN BOOK in 1998 called “Look Mom, It’s George! He’s a TV Indian.”

I haven’t seen NURTURE SHOCK but will look for it. For older–yet powerful books on the subject–see THE ANTI-BIAS CURRICULUM by Derman-Sparks, published in 1989. Here’s an ERIC digest based on her book: http://ecap.crc.illinois.edu/eecearchive/digests/1992/hohens92.html

There is a lot of excellent material. Ausdale and Feagin’s THE FIRST R: HOW CHILDREN LEARN RACE AND RACISM, first published in 2001 is another one I recommend.

As for children’s books, among the five I recommended for the SLJ article is Lacapa’s LESS THAN HALF MORE THAN WHOLE. Elsewhere I’ve written about Savageau’s MUSKRAT WILL BE SWIMMING. It is about a Native girl who is taunted for who she is, and how her grandfather helps her understand it. My article in Horn Book has additional picture books. There are newer ones that take on boarding schools. Nicola Campbell has two; look at Judith Lowery’s HOME TO MEDICINE MOUNTAIN. Tim Tingle’s SALTYPIE is excellent.

Part of why we (as a society) love books is because we believe they can empower us for the ways in which they reflect life. A pet dies? Read TENTH GOOD THING ABOUT BARNEY. We don’t necessarily shy away from hard subjects like that one (death) but we certainly do shy away from race. We do so, at our own peril, I believe, and because we do, we still find it necessary to have events like We Need Diverse Books. Not enough people read the Anti-Bias Curriculum when it came out. Groundbreaking as it was, it wasn’t the first time someone had looked at that subject. Native people started objecting to misrepresentations of who we were/are in the 1800s. In the early 1900s, Native parents in Chicago wrote to the school board about it. None of this is new.

I believe in the power of children’s books to help, but I’m also aware of their power to harm. You and I are deeply committed to children and their books. I believe that ending racism starts with young children, with teaching them about it from their childhood, so that it is something they carry with them into adulthood. Knowing it is there, knowing it is wrong… Doesn’t it seem logical that if we had more kids raised that way, it would make a difference in society?

My first paragraph above is incomplete. Here’s the rest of it:

If we don’t talk about race, studies suggest that our kids perceive ‘other’ to be bad. By adopting a color blind stance, we inadvertently communicate that other is bad.

Natalie–thanks for pointing people to those books. They’re in the SLJ article I did in November of 2013.

How about Julius Lester’s 2005, Let’s Talk about Race?

Great post, Betsy!

The first LGBT-parents book that comes to mind for me is In Our Mothers’ House, by Patricia Polacco. The two moms (one of whom is also quite fat, another kind of diversity!) have a multiracial, multiethnic family of adopted kids. There’s a horribly homophobic neighbor who doesn’t have the come-to-Jesus moment — she remains a hater. On the whole the community is accepting, but still, I wish it were a happier book! Does that make me naive? Maybe.

The best casual-diversity (love that term) book for LGBT parents I can think of is Everywhere Babies, with Marla Frazee’s killer illustrations. It’s up to the parent or caregiver-reader to point out the different constellations of family — oh, here’s two daddies, here’s two mommies, here’s a grandma or other older person who is the primary caregiver, here’s a solo parent, here are two parents of different races. I like that this is a book for very, very little kids that gives the adult an opportunity to editorialize without having to deal with a text itself that’s drearily didactic.

An aside: casual diversity is great in books and a real problem for me in tween live-action television (I’ve written about that, too)! Kids of color on Disney and Nick’s teen shows have no markers of identity beside their skin color — there’s always ONE kid of color in a sea of white, and that kid is essentially deracinated; he or she dresses the same as the white kids, has straightened hair (if she’s a Black girl), has the exact same interests, talks the same, is subject to the same body tyranny as the white characters. It feels tokenistic and yucky, and it feels like the visual equivalent of what Po Bronson and Ashley Merriman talk about in NurtureShock (I agree, great book) — the producers can congratulate themselves that they’re not being racist because hey, their show depicts a different skin tone, but then it’s never a topic of discussion or a marker of identity, and wheee there’s no discrimination and everyone’s exactly the same. I think it’s a distressing message to send: there’s no difference AT ALL. And because it’s tween TV, adults often aren’t watching and can’t discuss the mixed messages of the shows and their casting.

Oh! I also like Yoko by Rosemary Wells for little kids. Yoko brings sushi to school and all the other kids are shriekingly grossed out and horrified. We’ve seen these kids in Wells’s other school books, so they’re not demonized as bullies. (Another problem in picture books and some middle-grade novels, too — bullies are Other, not our friends or us.) They’re just kids, being clueless and insensitive about something they haven’t been exposed to. I think it’s a fun story that educates gently.

I’m so glad to see this conversation happening in an honest way.

So often, parents use a language of “What the kids can handle.” Almost always, I think the real issue is “what the parents are comfortable discussing.” But books like these are such a good way of getting everyone thinking/talking/pushing their own boundaries.

I’ll absolutely be circulating this list. Thanks!

Brilliant! Forgot that one.

Excellent, Debbie! I knew I could count on you to add to this. Indeed books can definitely do as much harm as good. With that in mind, I’m shocked that I don’t know the books you’ve listed here. Must find, stat.

Excellent. I was actually hoping for some alternative opinions on this and the point about the book being focused on parents vs. teachers is an excellent one. I haven’t said why this list I made exists, nor have I suggested how to use it. In this light, one would argue that it’s a list for parents rather than teachers, but as any public children’s librarian will tell you we get asked for this kind of list all the time.