new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: critics, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 29

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: critics in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

Isn't Charles McGrath a right voice in our time?

(Wait. Did that sound critical?)

This week the

New York Times Book Review asked Charles McGrath and Adam Kirsch the question:

Is Everyone Qualified to Be a Critic? It's a question I often ask myself. A question I've been asking myself for the past 20 years, in fact—throughout my reviews of many hundreds of books for print and online publications, my jottings on behalf of the competitions I've judged, and my meanderings on this blog.

What makes me qualified? Am I qualified? And do I do each book—whether or not I like it—justice?

I do know this: If my mind is dull, if I am distracted, if I feel rushed, if I've grown just a tad weary of this trend or that affect, I won't review a book, not even on this blog, where I own the real estate. Writers (typically) work too hard to be summarily summarized, falsely cheered, unhelpfully glossed. Reviews should only be treated as art (as compared, say, to screed or self-glorification). It's important, as McGrath notes, that we reviewers keep reviewing ourselves.

His words:

It’s surprising how much contemporary critical writing is a chore to get through, not just on blogs and in Amazon reviews but even in the printed paragraphs appearing below some prominent bylines, where you find too often the same clichés, the same tired vocabulary, the same humorless, joyless tone. How is it, you wonder, that people so alert to the flaws of others can be so tone deaf when it comes to their own prose? The answer may be the pressure of too many deadlines, or the unwritten law that requires bloggers and tweeters to comment practically around the clock. Or it may be that the innately critical streak of ours too frequently has a blind spot: ourselves.

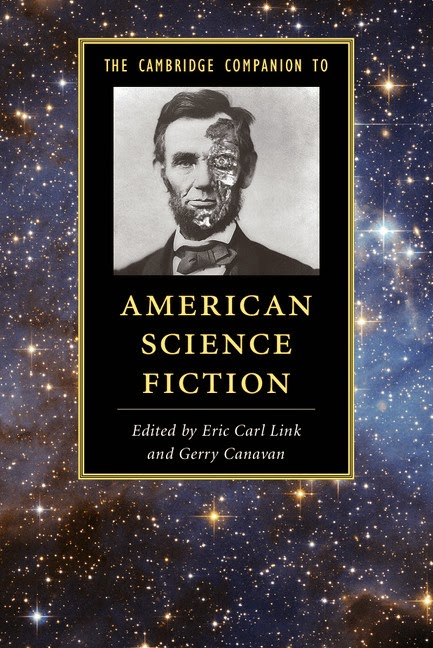

Cambridge University Press recently released

The Cambridge Companion to American Science Fiction edited by Eric Carl Link and Gerry Canavan, a sequel, of sorts, to 2003's

The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction edited by Edward James and Farah Mendlesohn. I bought the James and Mendlesohn volume at the first science fiction convention I ever attended, the Worldcon in Boston in 2004, and I think it's an admirable volume that mostly does its best to try for the impossible, which is to present a coherent overview of the history and scholarship of science fiction as a genre-thing (mostly in the Anglo-American mode). I have mixed feelings about the

Cambridge Companion to... series, because the volumes often feel like grab-bags and

pushmi-pullyus, a bit too specific for people looking for an introduction to the scholarship on a topic, a bit too general for people with knowledge of a topic. They often contain a few excellent individual chapters amidst many chapters that feel, to me at least, like they needed about 15 more pages. That's still, inevitably, the case with James and Mendlesohn's volume, but many of the chapters are impressively efficient, and as a guide for beginning scholars, the book as a whole is useful.

The new Link and Canavan book doesn't work quite as well for me, and it has a higher number of chapters that seem, frankly, shallow and, in a couple of cases, distortingly incomplete and sometimes flat-out inaccurate. With a topic limited to a particular geography, you'd think the editors and writers would be able to zero in a bit more. Some chapters do so quite well, but my experience of reading through the book was that it felt more diffuse and less precise than its predecessor, with annoying little mistakes like Darren Harris-Fain's statement that James Patrick Kelly's story "Think Like a Dinosaur" requires close reading to find its SF tropes (it's set on a space station and includes aliens; finding the SF tropes doesn't require close reading, just the most basic literacy). Despite the annoyance of little errors and the frustration of wild generalizations in many of the post-WWII chapters, I began to wonder if the big problem might be a matter of the volume's determination to focus on "American" science fiction, a determination that works very well for the chapters looking at pre-World War II fiction, but then becomes ... problematic.

The problem, though, might be me. I'm not at all the intended audience for the book, I have ideological/methodological hesitations about some of the framing, and I have a love/hate relationship with academic science fiction scholarship in general — feelings that are probably mostly prejudices unburdened by facts. (Sometimes, I have trouble shaking the feeling that SF criticism is still wearing training wheels.) At the same time, though, I'm also drawn to the idea of scholarship about science fiction and its related genres/modes/things/whatzits, because I am (for now) ensconced in academia and also have been reading SF of one sort of another all my life, off and on. I'm not particularly familiar with Eric Carl Link as a scholar (though I'm using his Norton Critical Edition of

The Red Badge of Courage in a course I'm teaching right now), but I've been following Gerry Canavan's work for a few years and I think he's a force for good, someone who is trying to keep SF criticism moving into the 21st century. Indeed, I just got back from the

International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts, where I heard Canavan deliver a truly interesting paper on posthumanism, Kim Stanley Robinson, eco-SF, etc.

In my more radical moments, I wonder if, to move into this century, we shouldn't just get rid of the whole idea of "American" science fiction, or at least the study of it as such. (Heck, in my

most radical moments, I wonder if we shouldn't get rid of the whole idea of "science fiction", but that's a topic for another time...)

Let's look at the book, or at least its premise and introduction. (I'm not going to do a blow-by-blow review of each chapter. If you must know, the chapters that seem to me most worth the time it takes to read them are Lisa Yaszek's "Afrofuturism in American Science Fiction", John Rieder's "American Frontiers", Karen Hellekson's "Fandom and Fan Culture", and Priscilla Wald's "Science, Technology, and the Environment".) The introduction by the editors serves various purposes, and succeeds impressively in giving a concise overview of 19th century American science fiction. If you want to know where to begin with American proto-SF, you could do a lot worse than to read that section of this intro.

The most provocative part of the introduction is the part that seeks to justify the book's focus on science fiction from the United States (there's no Canada or Mexico, so this isn't North American SF, though Margaret Atwood gets some passing mentions; there's nothing about South American SF; this is United Statesian):

The simple premise of the present volume ... is that the science fictional imagination is so fundamental to the arc of history across the so-called American Century that we might productively talk about a specifically American SF. Many of the ideas, themes, and conventions of contemporary science fiction take their roots in a distinctly American cultural experience, and so SF in America serves as a provocative index to twentieth- and twenty-first-century American culture, reflecting America's hopes, desires, and fears. (4)

I am an avowed skeptic of

canonical nationalism, and so my instincts are to tear into these statements, but at the same time there's a real truth to them: science fiction as a genre is deeply tied to origins in American pulp magazines and then in the paperback revolution of the 1950s, '60s, and 70s, as well as, to some extent or another, the dominance of blockbuster Hollywood over so much cultural production (although in some ways that also helps de-genrefy SF by absorbing the idea of the science fictional into whatever Hollywood product happens to be highly popular, whether

Star Wars or

The X-Files or superhero movies). Additionally, as this

Cambridge Companion makes clear, USian mythmaking is a key component to a lot of the foundational works of what we think of as genre SF — myths of individualist heroism, myths of the frontier (John Rieder's chapter tackles this head-on, which is one reason why it's among the strongest chapters in the book). For a long time, what we USians might call SF in other countries was different from American SF, even as American SF was derived from primarily European writers of the 19th century, especially Wells and Verne. One of the major differences was that it was in the US that an immigrant from Luxembourg,

Hugo Gernsback, successfully severed science fiction from other streams of fiction, distinguishing it not only from "literature", but also from all other types of popular and pulp fiction. The innovation was not simply a matter of definition or labelling, as that had been done plenty of times elsewhere, with terms like "scientific romance". Science fiction as a genre didn't need a definition, it needed a system. It was Gernsback who, in the late 1920s, not only gave SF its own magazine but also created ways for readers of that magazine to identify themselves as a discourse community — to be, in a word,

fans. It was in the US, then, that the production, distribution, and reception of SF as a genre system successfully began, and that system soon allowed for the dissemination of the values constituting it, values that were often stereotypically "American".

After World War Two, things get awfully complex, however, as genre SF becomes quite productively transatlantic, and as the space race and the Cold War affect global perceptions of technology and the future.

The New Wave, for instance, makes little sense from a purely US-centric standpoint, and yet the decade of the 1960s in literary SF — and all its repercussions — makes no sense without the New Wave. (Further, as Samuel Delany has pointed out multiple times, it should really be New Wave

s — Moorcock's New Wave was not Ellison's New Wave was not Merril's New Wave was not Cele Goldsmith's New Wave, etc. The way they diverge and overlap deserves attention.)

And yet, it's also true that American SF publishers and media producers have had more power and success overall than others, at least with English-language SF, and so their ideas of SF spread easily beyond US borders.

The hegemonic monster (hegemonster?) of US power in the second half of the 20th century deserves scrutiny, and science fiction could be a tool for such scrutiny, as I expect the editors of this book hoped to be able to at least begin to do, and as some of the chapters, do, indeed, pay attention to. We need, though, a

Cultures of United States Imperialism for science fiction, or a study of

Rick Perlstein's histories of US conservatism alongside a study of science fiction in the same era, or ... well, the possibilities are many, because science fiction is often a genre of power fantasies, and the United States is often a country fueled by such fantasies. (For all its messiness, Thomas Disch's

The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of at least asked some useful questions.) Such an intervention isn't really what

Cambridge Companions are about, however.

One of the dangers that the field of American Studies faces is the danger of re-centering American power just as we're beginning to de-center it in literary, cultural, and political studies. We can see the de-centering effort on a small scale with literary science fiction, where the rise of the internet has allowed a nascent movement of global SF to grow, and where there is a stronger awareness than ever of writers and audiences from around the world. There's a long way to go, but if the 20th century was an American century, and also a century of American science fiction, then perhaps the 21st can centered differently.

The editors of the

Cambridge Companion hint toward this in their introduction. They are no American jingoists. But they also write: "The vast canon to which all contemporary creators of SF (in all media, forms, and genres) respond is thus (for better or worse) tightly linked to American ideas, experiences, cultural assumptions, and entertainment markets, as well as to distinctly American visions of what the future might be like" (5). I think that statement is false in one important way — I would say "

most creators of anglophone, genrefied SF" rather than "

all contemporary creators of SF (in all media...)" etc, because I think this rather all-encompassing generalization neglects certain tendencies in British SF that have been influential, and it completely wipes out non-US/UK SF. The result is an unfortunate and I expect unintentional valorizing of UScentricity, unless it is premised on a very narrow definition of SF, which it seems not to be. But this is the danger of nationalistic scholarship, especially when performed by scholars from within a particular nation — they remain blind to the world they cannot see, and so the map they create is one where the US is in the center and is bigger than any other area.

Americanness was, obviously, not quite so much of a problem for the James and Mendelsohn

Cambridge Companion, where many of the contributors were not America. Nonetheless, it was very much not a

Cambridge Companion to Global Science Fiction — a topic too big for the slim confines of any one book in the

Cambridge Companion series. (To see some of the scope, look at the

International tag at the

SF Encyclopedia site.)

There is no denying the centrality of the US to science fiction in any way that

science fiction makes sense as a label. (

For better or worse, as Link and Canavan say.) But for myself, I wonder what it means to study American science fiction solely, much as I wonder what it means to study American literature solely, or American anything solely. Or to call it "American".

And yet to deny the centrality of a thing called "American literature" is foolish and distorting, even though, in my more idealistic and la-la-land moments, I might want to. We are not the world? We are the world? We are ... what?

As I think about the introduction to this book and my inchoate (if not incoherent) resistance to the

American in

American Science Fiction, I can't help but also think about a paragraph in Aaron Bady's recent, important

Chronicle of Higher Education essay,

"Academe's Willful Ignorance of African Literature", a paragraph that I have no answers for, and which nags at me:

I worry that as Americanists move into “World Anglophone” literature, the world outside of Britain and the United States gets included in theory, but will continue to be excluded in practice. As crass it might be to use “world literature” as a shorthand for “the rest of the world,” the alternative might be worse. I worry that the actual effect of rebranding English departments as “World Anglophone literature departments” would only normalize the status quo. Will their survey of Anglophone letters still consist of dozens of scholars working on British and American literatures and a single, token Africanist? That might be the best-case scenario. For all its flaws, at least the term “postcolonial literature” recognized on which side of the global color line it located its subject, and recognized how much work was yet to be done.

When thinking of "American science fiction", I can't help but think of all that that term

doesn't encompass, and perhaps my struggle with this

Cambridge Companion is that my own deepest interests are in what sits at the margins, what defies the definitions, what lurks beyond the scopes.

(I told you I'm not the audience for this book!)

I wonder, too, why there isn't more scholarly attention to things like

Analog magazine and

Baen Books. Neither appears in the index to

The Cambridge Companion to American Science Fiction, and the sorts of things published by

Analog and Baen don't seem to get much discussed by SF scholars. And yet shouldn't a book about

American science fiction provide more than just the most passing of passing mentions to Jerry Pournelle and Larry Niven? The ascent of science fiction in the United States parallels the ascent of Reaganism and neoliberalism, and how is it that among the various references to

Star Wars in this book there are none (that I found, at least) to

Ronnie's own beloved version? This

American Science Fiction needs more

Amurrican science fiction, more

Newt Gingrich, more

Rapture culture, more

survivalism. Too much academic SF criticism cherry-picks favorites to valorize, and since most academic lit critics are armchair leftists of some sort or another (myself included), we get lots of

Left Hand of Darkness and not nearly enough

Left Behind.

(I have no good transition between these paragraphs, so I hope you'll pardon me this momentary aside to admit it. Hi, how are you? Thanks for continuing to read this rambling post, even though I'm sure you have something better to do. We're almost done. Shall we get back to it?)

To set down scholarly stakes within a realm called

The American not only risks valorizing an already highly valorized Americanicity, but it also risks seeing things in a narrower way than the creators of the works under study themselves did, and I firmly believe that criticism should add breadth and depth to material rather than narrowing it, should give us

more techniques of reading rather than fewer. This is my problem with some versions of canonical nationalism: they are procrustean, and miss the ways writers, for instance, learn from a variety of materials that are not so geographically bound. Among scholars, there's been in recent decades more of a push for, for instance, a view of transatlantic writing and thinking — of the

Black Atlantic, of

transatlantic Romanticism and

transatlantic Modernism(s).

"American" is not only geographical but ideological: the mythography of Americanism. Tracing the flows to and from that ideology is especially interesting to me, particularly as a way to try to interrupt those flows, or at least look at their edges, cracks, and pores. (

The Cambridge Companion to Anti-American Science Fiction, anyone? No?) I like that Link and Canavan end the book with a chapter titled "After America", and though I have reservations about the chapter itself, which isn't nearly ambitious enough, the gesture seems necessary for this age: to at least imagine a move beyond the centrality of US power and US dominance, to change the perspective and shift our lenses. Certainly, as global warming threatens to eradicate most life on Earth, the moral imperative of our age is to move beyond any one nation, to perceive the planet entire, and to do what so much science fiction has aspired to do, even if it has almost always failed: to look at things from a broader perspective.

What if "After America" were to mean after the idea of America, after the dominance of the nation, after the discourse of Americanness? (America is just so 20th century, dude.) By ending with "After America", this

Cambridge Companion includes the seeds of its own destruction. A worthwhile move, it seems to me. But then, I like books that want to destroy themselves.

I admit it - until now, I'd never read The Picture of Dorian Gray. Oh, I knew, more or less, the plot. But when I needed to read Oscar Wilde's horror story for a novel I'm just starting to write, there wasn't a handy copy in the house, so I got it (for free) as part of a kindle Penny Dreadful multi-pack - including The Horrors of Zindorf Castle AND Jack Harkaway and His Son's Adventures in Australia, which, co-incidentally, I also didn't own.

But did you know The Picture of Dorian Gray was first published in this magazine in 1890?

In full. Plus a Preface. Plus a whole bunch of other fiction and articles and biography and - I'd love to read this bit - 8 pages With the Wits (illustrated by leading artists). How's that for 25 cents?

But here's what I want to post about. What Oscar Wilde said, in his Preface, about critics and criticism, because it is both a witticism and a balm. He said:

"... the lowest form of criticism is a mode of autobiography. Those who find ugly meanings in beautiful things are corrupt without being charming. This is a fault."

Is it merely an elegant way of saying, "Aw, poop, they're just jealous"? I don't care. Next bad review any of us gets, I recommend this as our mantra. All together now ...

This is a fault.

Joan Lennon's website.Joan Lennon's blog.

Back in January, having imbibed too many book reviews and flame wars, I

spouted on Twitter: "Most critical writing could be summed up as, 'My god is an awesome god! Your god sucks.'" That especially seems to be the case with so much writing about science fiction, which is less rigorously analytical than it is theological.

Let's look at two examples.

Adam Roberts's new Guardian essay on science fiction and politics reminded me of a provocative essay in

the current issue of Science Fiction Studies,

"Fascism and Science Fiction" (JSTOR) by Aaron Santesso.

Here, I'm not going to wrestle with their arguments so much as speculate (perhaps irresponsibly, erroneously, ridiculously) on what itch such arguments scratch, because though I am skeptical of the overall thrust of both pieces, I don't find either to be especially bothersome. As I read each, I realized that I didn't understand the desires and assumptions that motivated them, because they are the desires and assumptions of a religious denomination I don't adhere to. I've explored and dabbled with various sects of the church of science fiction since childhood, and a part of me still very much wants to be a believer, but I just can't make the proper leaps of faith. Call me Doubting Matthew.

To show the theological import of the two essays, we'll have to look first (briefly, inadequately) at how they argue their cases. Let's start with Roberts. A key sentence:

Asking whether SF is "intrinsically" leftwing or rightwing is dumb, since literatures are not "intrinsically" anything. But I'm tempted to thump the tub nonetheless.

"This is dumb, but I will do it." I admire the honesty. This is a leap of faith admitted boldly and in the open.

And so Roberts leaps and thumps:

Conservatism is defined by its respect for the past. The left has always been more interested in the future – specifically, in a better future. Myriad militaristic SF books and films suggest the most interesting thing to do with the alien is style it as an invading monster and empty thousands of rounds of ammunition into it. But the best SF understands that there are more interesting things to do with the alien than that. How we treat the other is the great ethical question of our age, and SF, at its best, is the best way to explore that question.

This is a straightforward version of dogma offered by more abstruse, monkish scholars such as Darko Suvin, Fredric Jameson, and Carl Freedman (the holy trinity of Marxist SF critics). Against these ideas, Santesso addresses the tendency to see SF as inherently progressive, or to define "good SF" as SF that agrees with the (Marxist) reader's ideology:

So the critical argument, as it stands, is that the “generic tendency” of sf is progressive, that its themes are naturally progressive, that its structures are naturally progressive. I suggest, in response, that the claims one can make about the inclinations of a genre if one concentrates on certain strands and tendencies of the tradition are limited only by the strands and tendencies chosen. Over the remainder of this essay, I will argue that certain other strands of sf—since sf as a whole (encompassing everything from cyberpunk to military science fiction, at the very least) is indeed hardly politically unified—can be recognized as anything but “naturally” progressive, instead being more strongly allied with fascist politics. Furthermore, certain foundational tropes and traditions of the genre carry the DNA of fascism, as it were, to the extent that even liberal, progressive authors working within the genre’s more refined strains often (inadvertently) employ fascistic tropes and strategies. These tropes and strategies interrupt and disappoint certain ideological expectations advertised as, or assumed to be, native to the genre.

Both writers explicitly recognize that this search for one, true SF is a fool's errand, but both play the fool — Roberts admittedly, Santesso more circumspectly, but just as strongly. They are defenders of the faith.

Santesso's essay does a good job of delineating fascist tendencies within particular stories and types of stories. His essay seems to me to be a useful beginning, a sketch of analytical possibilities that would benefit from being expanded, and Santesso's careful definition of the term "fascism" certainly allows readers to expand the ideas themselves. (A good companion to Santesso's work is Barton Paul Levenson's "The Ideology of Robert A. Heinlein" in

NYRSF 118, April 1998, which similarly applies a relatively precise definition of fascism to specific texts.)

Santesso's final paragraph is dense, but it's worth working through:

Given his influence on progressive sf criticism, we may give the last word to Jameson, and in particular his celebration of the Brechtian notion of plumpes Denken (“crude thinking”), which he defines as the postulate that even the most subtle, academic, or experimental “neo-Marxist” works must contain a core element of “crude” or “vulgar” Marxism in order to qualify as “Marxist” at all. Jameson alludes to plumpes Denken in order to make a point about science fiction: “Something like this may have its equivalent in SF, and I would be tempted to suggest that even within the most devoted reader of ‘soft’ SF—of sociological SF, ‘new wave’ aestheticism, the ‘contemporaries’ from Dick to the present—there has to persist some ultimate ‘hard-core’ commitment to old-fashioned ‘scientific’ SF for the object to preserve its identity and not to dissolve back into Literature, Fantasy, or whatever” (Jameson 245). Might it also be the case that the fascist energies and ideas of pulp sf are precisely the kind of identity-confirming “core” or definitional element that makes it possible to speak of “science fiction,” even when discussing literary, progressive sf? It is understandable that progressive critics would wish to distance themselves from both the aesthetics and the politics that accrued to a generation of stories featuring scenarios of the Golden Races vs. the Scaly Ones variety. But to deny that politics altogether, to claim that it belongs only to the past, is to evade a serious investigation of what makes the genre work, what gives it its identity and indeed its appeal. It is, ultimately, a denial of “science fiction” itself as a genre worthy of discussion, for surely the point of genre criticism is to identify and trace the various constitutional energies, themes, and plots that animate a form and in doing so account for all its variant strains and trends, not just the ones that accord well with a narrow set of critical pieties. To speak of “science fiction” at all is to admit to certain links and ideological ties that go beyond subject and setting, leading readers and critics into unexpected places and opening up unexpected connections. One cannot simply disown unwanted relatives or pretend not to recognize their features when they pop up in later generations. It is, indeed, precisely those ancestral presences—sometimes odd, sometimes eccentric, sometimes distasteful—that give science fiction its remarkable diversity and continuing vitality.

I'm not entirely convinced by many of the premises here*, but I'm fascinated by the continuing appeal of the desire not simply to define science fiction, but to define it toward a particular ideology, even when the writer knows and admits that this is a simplification or just "dumb".

The assertion that "good" science fiction is, in the view of Roberts et al., "progressive", is a statement that serves to set up criteria for true faith and for apostasy. (It's analogous to the use of the term "literature" to mean "that writing which I value and consider worth study".) Such a desire is similar to the one that propels people to claim that science fiction began with Mary Shelley or Newton or Lucian or Gilgamesh or the Big Bang, all of which are also ideological claims to an origin story that suits the storyteller's self-conception (or, if not outright self-conception, then at least the theological denomination they have chosen to associate with).

The stories told of science fiction are stories that reflect well on the storyteller. If the storyteller is an avid reader of science fiction, then the story is one that justifies that reading. Often, it's the fannish story of SF being somehow at the heart of literature, and therefore worthy of respect and study and love (as opposed to the "mundane" literature of a false church). Sometimes, it's a story of SF being the superior denomination. (My god is an awesome god!) One is not just a reader of science fiction, but a

proud reader.

Adam Roberts's

Guardian piece is perhaps best described as an example of faith-based writing. Lots of people of faith have written brilliantly, have done great things in the world, etc., so I don't mean this as a condemnation, and Roberts is particularly clear-eyed about his faith. He may be proselytizing, but he's perfectly aware that that's what he's doing. He's like a Campus Crusade for Christ guy standing out in front of the library, randomly accosting people with, "Hey, do you have a minute for Jesus? Jesus is cool!"

Aaron Santesso's essay is a useful corrective to the faith-based initiatives of the One True Church of SF missionaries (for instance, it would be interesting to read Santesso's approach to Iain Banks alongside Roberts's), but Santesso ends up giving in to the theological impulse himself by offering a story of original sin. Perhaps we could call it a Calvinist approach to SF dogma. He gives us an Old Testament sort of god, all grumpy and authoritarian and given to genocides, while Roberts sees science fiction more as a hippie Jesus. This unites the two essays, for Santesso has faith that science fiction can achieve its own new testament, and Roberts seems to think it already has.

As I said, I'm not separate from all this myself, even if I don't understand the fundamentalists and evangelicals. In many ways, I admire and even envy them their leaps and faiths. Perhaps their dogma is more honest than my anti-dogma, which is little more than the habitual uttering of, "Yes, but—" I have my own gods, my own idols and rituals and sacred texts. In that way, perhaps personal taste is always religious, always faith-based. Despite all attempts to figure out the empirical (or ideological) engines of taste, the explanations remain inadequate against the mysteries. Perhaps our passions are not only best expressed but best maintained through expressions of ecstasy. Perhaps faith is the best way to organize our desires, to give meaning to our pleasures and displeasures.

I'm a doubter, and so always and forever chained to

maybe and

perhaps...

Perhaps your god

is an awesome god. Or, perhaps life is richer and more coherent if we believe in a god (or pantheon) that is an awesome god, regardless of whether such a belief itself is rationally justifiable. Maybe we need more tub thumping dumbness, more leaps of faith. Maybe...

Or maybe it's your god that sucks.

---------------------------------

*My own proclivity is to view SF as a set of discourses sustained and propagated by a network of discourse communities, all of which can and should be historicized — a position certainly not opposed to Jameson or Santesso, but oblique to them.

I got caught up in the hype, got curious, and found a way to watch

True Detective. It's my kind of thing: a dark crime story/police procedural/serial killer whatzit. Also, apparently the writer of the show, Nic Pizzolatto, is

aware of some writers I like, and even one I know,

Laird Barron. (Hi Laird! You rock!) What struck me right from the beginning was the marvelous music, selected and produced by the great

T-Bone Burnett, and the cinematography by

Adam Arkapaw, who shot one of my favorite movies of recent decades,

Snowtown, and also the very good film

Animal Kingdom and the marvelous Jane Campion TV show

Top of the Lake. Something about Arkapaw's sensitivity to color, light, and framing is pure mainlined heroin to my aesthetic pleasure centers. If I found out he'd shot a

Ron Howard movie, I'd even watch that.

So many other people have discussed the show that there are now, I'm sure, nearly as many words written about it as there are words in Wikipedia. My own opinion of the show is of no consequence, though for the curious, here's what I said about it on Jeff VanderMeer's Facebook page, where some discussion was going on: "

I liked the music, cinematography, most of the acting and directing, but thought the writing was all over the place from pretty good to godawful. And episodes 7 and 8 were like the Goodyear blimp deflating mid-air and landing in a bayou of drivel. (The stars, the stars! Use the Force, Rust! The Yellow King is YOUR FATHER!!! Oh, wait...)"Much more interesting to me is the discourse around the show. Why did this show inspire such a fanatical response? Why did we feel compelled to respond? Zeitgeist, genre, etc. probably all play into it, but a fuller answer would require some time and research, particularly about how the show was marketed and where and how it first caught on. I'm enough of a pointy-headed academic to hope one day for a whole book about the construction of True Detective's appeal, something that doesn't neglect the material aspects: budgets, advertising, Twitter. I'd also like to see analyses of fan responses to mystery/crime shows — for instance, a comparison of fan speculations between seasons 2 and 3 of Sherlock and fan speculations about the mysteries of True Detective before the finale. The choice in season 3 of Sherlock to offer a relatively acceptable but not definitive answer to the mystery of how Sherlock lived was, I thought, quite smart, because even though the creators probably had (unlike Conan Doyle) an idea of an answer when they wrote Sherlock's "death", they realized by the time it came to write season 3 that no answer they could provide would be satisfying after two years of fan speculations. True Detective took a different approach, partly because they didn't realize viewers would react the way they did, or that the show would be subject to so much ratiocination, and so they gave a rather ridiculous and clichéd end to the mystery, one that made not a whole lot of sense and tied up only the most obvious of loose ends. Pizzolatto's interest was more in the characters than the plot, or perhaps not even the characters so much as the mood and the projection of an idea of complexity rather than any actual complexity.

I am, myself, now falling into exegesis more than I intended. (It's fun to posit signs as wonders!) Really, what I wanted to do was collect a few writings about True Detective that I particularly liked, that got me thinking. The show has inspired some good writing about it. Here then, before they get lost in the din, are a few fragments I'll shore against these ruins........Jacob Mikanowski at LA Review of Books:The Southern Louisiana of True Detective is part truth and part myth. But just by showing so much of it, the show puts us in contact with its real history, even if it doesn’t spell everything out. But there are hints, especially on the margins. There’s the history of pollution, visible in the omnipresent cracking towers and in the condition of Dora Lange’s mother as well as the relative of another victim, a one-time baseball pitcher disabled by a series of strokes. There’s Louisiana’s French and Spanish past, glimpsed momentarily in the Courir and in a stray allusion by Rust to the Pirate Republic of Barataria. And then there’s the history of segregation and racism, barely present except for the suggestion that the schools most of the victims attended were a way around busing — like the “segregation academies” that sprang up in different parts of the Deep South as a response to Brown vs. the Board of Education.

In my dream version of the show, the detectives are historians or archivists. They could work equally well somewhere in the Mississippi Delta or Eastern Poland. The crimes they investigate are buried in the past, and the thing they realize eventually isn’t just that everyone knew, but that everyone was complicit. Coincidentally, while the first episodes aired, I happened to be reading Trouble in Mind, Leon Litwack’s magisterial history of the lives of Black Southerners under Jim Crow. And although I shouldn’t have been, I was shocked by his account of lynching — at how common it was, how popular, and how public. The audiences that gathered for lynchings were huge, and their appetite for suffering — burning and other tortures — as spectacle couldn’t be satisfied by mere killing. Children even played their own games of hanging and being hung. True Detective doesn’t go there — but in the sense it creates, of a past that infects the present, of ritualized violence that doesn’t end even after it officially disappears — it starts to open the door.

Dustin Rowles at Pajiba:That is literary inefficiency, and while it’s easier to understand in the context of a longer season in the midst of a longer series where it’s often necessary to pad out the episodes, and where showrunners are often forced by more demanding production schedules to wing it along the way, Pizzolatto had only eight episodes to write and the ability to plan out the entire season in advance. The irony, of course, is that he still had all the ingredients necessary to create a more compelling ending, and yet he still he chose to stick with the simpler, “There’s a Monster in the End” storyline. It’s a shame, too, because Pizzolatto obviously has a deep understanding of literature, and yet he chose the television ending over the literary one. Unfortunately, it seems, he knows how to introduce literary allusions, but he doesn’t show us he knows how to utilize them.

Joseph Laycock at Religion Dispatches:Of course, there’s nothing inherently wrong with a happy ending. But the final message of True Detective reinforces a dangerous mythology that’s already endemic in American popular culture. The brutal misogyny of the heroes, their willingness to commit all manner of felonies—this was not a Nietzchean tale of those who hunt monsters becoming monsters themselves. Instead, this is a moral universe where anything is justified as long as your opponent is “truly” evil and good “gains some territory.” This is about as far from Lovecraft’s cosmic horror as one can get.

Spencer Kornhaber at The Atlantic:Certainly Marty’s violence and sexism isn’t appealing; certainly Rust deserves the eye rolls that other characters threw his way. But creating flawed heroes isn’t subversive—it’s doing exactly what any decent fiction writer is supposed to do. A subversion would have been to make those flaws figure into the main narrative in some unexpected but crucial way. Maybe the “good guys” botch the case. Or maybe, per the theories mentioned before, they’re connected to the murders in ways they don’t understand till it’s too late.

Instead, both main characters got a fair amount of vindication in the end. Marty’s family doesn’t seem to hate him quite as much anymore. Rust believes in the afterlife now. They both go backslapping into the night. All of this comes from them catching a killer of women and children. So for the zillionth time in Western pop culture, men (straight, white ones at that) get psychic rewards for valorously risking themselves on behalf of the weak.

Susan Elizabeth Shepard at The Hairpin:If you're going to make a dead sex worker the inciting incident for your story, if one of the central characters is defined by his rage about the sexual purity of the women in his life, it needs to pay off in the form of story advancement and character development, otherwise it's just gratuitous, sensational, "edgy." And for the last several episodes, it's become clear that the only satisfying way for the mystery to end is for Rust or Marty to be the killer. But we're gonna get some dumb conspiracy of Louisiana good ol' boys who worship the devil, which is going to be unsatisfying and also not give the proper payoff to all that violence against women, which then becomes just so many witchy antler decorations with no clear meaning.

Matt Zoller Seitz at Vulure:Marty's hypocritical attitude toward his wife and daughters is positively Scorsesean in its misogyny. Never for a moment does the show pretend that he's got the right idea about fidelity, fatherhood, or anything else related to the women who live under his roof. He's got a gangster's idea of manhood: I'll do what I please, and you do whatever I tell you. He's the king of his castle, everyone else is a serf. Rust, meanwhile, is haunted equally by the death of his daughter (and subsequent guilt over his failure to preserve his marriage afterward) and his rocky relationship with his father, to whose home state, Alaska, he briefly returned; he's destroyed by his inability to live up to an unrealistic standard of manly strength, goodness, and patience. It makes both dramatic and rhetorical sense that Marty and Rust's interrogators would be two black men, and that many of the detective's most mortifying and self-destructive moments stem from their inability to deal with women in an honest and non-condescending way. The show's disinterest in race relations and inability to resist gratuitous T&A shots damages its credibility greatly in this department, but the notion that True Detective is purely a white male supremacist fantasy is not remotely supported by the evidence.

Lili Loofbourow at LA Review of Books:Ask a woman whether Errol Childress matches the monster at the end of our dreams — I doubt you’ll get many nods. But there is a monster we might dream about in True Detective, and he’s everything a monster should be: murderous, violent, deeply sympathetic, and totally adept at spinning the Cohles of the world to his side. Here’s to TV’s greatest and most affable monster, Marty Hart.

Henry Farrell at Crooked Timber:Another interpretation, which seems to me to be equally plausible, is that the catharsis of the closing episode is false, and deliberately so. The darkness continues. Marty’s inattention to his family has had profound costs. The show strongly suggests that one of Marty’s daughters has been the victim of sexual abuse, in ways that mirror the detective story, just as the detective story mirrors the story of Marty’s family. Marty doesn’t seem aware of this at all. If Marty and Rust conclude that the light as winning, it is only because they fail to see the darkness that surrounds them, and cannot see it, so long as they continue to live in a world of purely brotherly camaraderie, a war of light against dark where one responds to male violence only with more violence and leaves women’s business to the women. Even when you are confronted with your true situation, you cannot necessarily free yourself from it. The detective’s curse means that you do not escape from Carcosa. You only think that you do because you are willfully blind to the Carcosa that surrounds you, the labyrinth made of the circle that is invisible and everlasting.

As I was writing a comment over at Adam Roberts's blog (about which more in a moment), I realized I had various items of the last few days swirling through my head, and it all needed a bit of an outlet that wasn't a muddled comment on Adam's blog, but rather a potentially-even-more-muddled post here.I don't have a whole lot to say about these things, and I certainly have no coherent argument to make, but they've congealed together in my mind, so here they are, with a few lines of annotation from me. Most of these things have gotten a lot of notice, but they haven't gotten a lot of notice

together.

First, Jonathan Franzen is once again

reprising his role as Grumpy Old Man With Fist Raised In The Air Complaining About The Kids These Days. I read half of it and couldn't keep going because, ugh,

Jonathan Franzen. Really, I wish he'd just donate his millions to charity, take a vow of poverty, and go wander through the world and revel in his saintliness. And preferably never write anything ever again. But that's just me. As the deluded sheeple on the Twitter say, YMMV.

It's not that I don't think we're doomed and our culture insipid. I do. But it's been that way for a long time, especially in the United States. We're very good at being insipid and creating doom. Those are perhaps our greatest national talents. As Ta-Nehisi Coates

recently said in a completely different context: "I expect the worst of everyone to win--and take humanity down with them. I get sad about that sometimes, but I am mostly resolved." That could be my credo. The way we live now is a

J.G. Ballard novel.

Then there was

Christopher Beha's blog post,

reprinted by Slate, about how the

New York Times Book Review should only cover "Holy Crap" books (

hehehehe he wants them to write about crap hehehehe). Pretty much all of his assumptions are wrong,

as Nick Mamatas gleefully pointed out, and his blazingly ignorant idea that fascinating writing about genrefied books is impossible can be disproved by such things as, for instance, some of the reviews at

Strange Horizons, some of the

reviews and

writing at

LA Review of Books, academic articles at such places as

Science Fiction Studies, etc. etc. — but I basically agree with him in a more general sense, which is: it's nice to read long, thoughtful, insightful writing about challenging books, books that are hard to get a handle on at first glance. Which is one reason why I don't regularly go running to the

New York Times Book Review for my litchat. It's a book review, the last one standing at a newspaper. If even a specialty publication like

Bookforum has had to add shorter reviews, more media and political coverage, etc. to help maintain even a small audience, the

NYTBR sure isn't going to follow Beha's advice — because his advice to the

NYTBR is to commit suicide. They'd be better off putting a Jennifer Weiner novel on the cover.

Which brings us to Adam Roberts, who has a really provocative (well, to me) post up at his blog titled

"On YA", but only partly about YA.

My comment on the post gets to my disagreement with most everything I read him as saying. I am convinced I must be misinterpreting his ideas terribly, and I honestly look forward to him correcting me, because it looks to me like the Adam Roberts who

caused a row about the mediocrity of the Hugo Awards in 2009 has now seen the light and found the Jesus of Popularity! Is! All! This cannot be true. I must be misreading him.

One of Adam Roberts's points is the counter opposite of Christopher Beha's — that the "genius of the age" in literature right now exists in the realm of genrefied fiction and, especially, YA. (Things get murky in the post because "genius of the age" seems to then get conflated with "popular". But, again,

I must be misreading.) This is not a claim I can really discuss in an informed way, because I only occasionally read YA novels, and though some, like M.T. Anderson's first

Octavian Nothing novel, seem to me among the great literature of our time, the field itself is really not my thing. Kameron Hurley

explained well why she doesn't write or often read YA, and my feelings are similar: the sorts of things that typically fit a book into the YA market, and that are

desired by YA readers, are not the sorts of things that make me want to read a novel. Inevitably, then, I will miss reading some extraordinary fiction, but we will all miss reading lots of extraordinary fiction because there is more extraordinary fiction out there than any of us have time to read. That is the curse of the reader. If Roberts is right and YA is the genius of our age, then the curse of our culture may be that it aspires to be a 16-year-old.

Roberts's whole argument seems to me to confuse cultural history, cultural analysis, and aesthetics. I'm not an art-for-art's-sake aesthetic puritan; I am completely convinced that how we interpret and value art is determined by other social and cultural values, but I do think there is a distinction — a valuable distinction — between the ways that we value a cultural product and the ways that a cultural product has power within a culture. Here's an example: I've spent the last year and a half or so watching, reading about, thinking about, and trying to write about American action movies from the 1980s. I think they're immensely culturally and politically important and can tell us a lot about the era. I don't think any of them are particularly good movies, though some have certain virtues, quite a few are fascinating to think about and analyze, and some are entertaining even after multiple viewings. They did, in fact, embody a certain genius of their age, the same sort of genius possessed by Ronald Reagan, although overall I think that genius was a pernicious one. But it was effective and we're still feeling the ripples in our culture and politics. That's no argument for the Oscar to have gone to

Rambo II, though. Certainly,

Rambo II is a far better exemplar of its time than any of the actual winners, but that's just because, as usual, the awards

went to a bunch of ostentatiously mediocre movies. This was the year of

Ran, Shoah, Brazil, and

Come and See — masterpieces that mostly escaped Oscar's notice. But the point of the Academy Awards is not to hail masterpieces or find the movies that most embody the era: it's to congratulate Hollywood for being Hollywood. We look to the Oscars to see how Hollywood perceives itself. To ask for more is to misperceive how those awards work. Similarly, popularity (

Rambo II, etc.) primarily shows us what masses of people consider potentially entertaining enough to spend money on. Movies like

Ran, Shoah, Brazil, Come and See exist outside both lenses, as do the great books and music of whatever year. And by "great" I mean the socially-constructed-but-nonetheless-perceivable-across-multiple-eras-and-geographies complexity and individuality that distinguish, say,

Kafka from

the bestselling novels in the U.S. in 1924.

I thought of these three writings by these three writers (Franzen, Beha, and Roberts) together because there seems to be some sort of conversation to be had among them and their respondents about how we value culture and what we get from it, particularly either cult or elite art — which may be the same things, a cult being a kind of elite and an elite being a kind of cult. Being me, I would also want to add in more about

cultural capital, and seek out areas of agreement while also asserting that, of course, we are doomed ... but really I'm just indulging in a fantasy: what if our three boys were stuck on a stage together in front of an audience? What might they talk about? Or, even better, what if we put them in a room with some YA novelists, crime and romance and SF writers, people published by

FC2 and

Dalkey Archive, former jury members of various awards,

VIDA members, members of the

Carl Brandon Society, some high school English teachers, at least a few librarians, passionate David Eddings readers, a couple of anarcho-communists, some radical queers, and a few random people off the street ... what directions might the conversation take then...?

My brain begins to melt just thinking about it.

Dear Dwight Allen:

Thank you for letting me know about

your Stephen King problem (henceforth, SKP). Many people let these problems go, thinking they're not particularly important or, ultimately, relevant to anyone other than themselves, but the science shows that letting these problems linger encourages them to fester, and once they fester they can then lead to all sorts of complications and an endless array of other problems (most commonly, J.K. Rowling problems and J.R.R. Tolkien problems, which themselves can lead to entire textbooks of other problems.) Such suffering becomes an infinite sprawl of frustration, guilt, pain, and, often, anti-social behavior and anal warts.

To assess your treatment needs, let's analyze some of your history and symptoms.

Failure to quarantine. It is clear from your history that you remained healthy after occasional contacts with contagions (most notably in New York City [notable site of contagions of all sorts] in the company of a publishing employee [notable purveyors of marketing-induced illnesses] whilst "possibly" drinking "too much bad beer" [do you think there is such a thing as "enough" bad beer?]. You note that your infected friend had alleviated or at least hidden some of his symptoms with regular infusions of Pynchon, Nabokov, and Gass, but as you now must know, these are not effective medicines against SKP any more than a breath of filtered air is a remedy for the carcinogenic effects of smoking a cigarette). You health after said contact was, though (as is obvious now) relative, because had you truly been healthy, you would not now have a problem. I hope this will be a lesson to you in the future.

It is absolutely essential to quarantine bad influences at the moment you begin to suspect their healthfulness. It is always better to be safe than problematized. First, the contagion infiltrated your brain. Then, like an insect laying eggs beneath your skin, it incubated, eventually bursting through to present as full SKP.

You identify your own failure clearly, even if you don't acknowledge it as such: "During my college and graduate school years and then in my post-graduate working life, I’d read, in addition to much commercially successful literary fiction, a fair amount of genre fiction." It is good that you have separated the healthy ("literary fiction") from the somewhat contaminated ("commercially successful literary fiction") and from the pure contagion ("genre fiction"). But exposing yourself to the contagion in any form is, for roughly 75% of the population, eventually fatal. To be honest, your middle category is an illusion, like being only somewhat pregnant. There really is no middle ground. (As we will discuss later, it is very important to maintain only 2 categories for any sort of healthy judgment.)

Notice how many times you return to the contagion once you have encountered it fully. First,

Christine, then

Pet Sematary, then (saying, "I thought I’d try another King novel, a later one, to see if his writing had changed over the years")

The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon and

11/22/63. You know, of course, that such exposure is dangerous, and you're now fully aware of the effect, but it's important to be absolutely honest about the steps along the way. Remember, too, that contagion and addiction often present similar symptomatic profiles.

A side note: According to your account, one contagion you did manage to avoid was hipness. You write: "Strangely enough, I’d developed my taste for crime fi

Yesterday, I posted

a mocking attack on Prometheus that also linked to other attacks. I hated the movie, and so did plenty of other people.

But I don't want to give the impression that it is

Friday the 13th Part XXVI: Jason vs. Maximus Prime. (Actually, that movie could be

awesome!) Plenty of perfectly intelligent moviegoers have not merely enjoyed

Prometheus, but embraced it. Adored it. Gone to see it more than once.

So, for some balance, here are four quotes from reviews and comments on the film that view it more positively than I or the people I quoted yesterday:

Roger Ebert:Ridley Scott's "Prometheus" is a magnificent science-fiction film, all the more intriguing because it raises questions about the origin of human life and doesn't have the answers. It's in the classic tradition of golden age sci-fi, echoing Scott's "Alien" (1979), but creating a world of its own. I'm a pushover for material like this; it's a seamless blend of story, special effects and pitch-perfect casting, filmed in sane, effective 3-D that doesn't distract.

Andrew O'Hehir:...“Prometheus” damn near lives up to the unsustainable hype, at least at the level of cinematography, production design, special effects and pure wow factor. This tale of a deep-space mission late in the 21st century, several decades before Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley and the crew of the Nostromo will discover an abandoned alien spacecraft and its sinister cargo, is a sleek, shimmering, gorgeous and often haunting visual mood piece. No other recent science-fiction film, with the sole exception of “Avatar,” has created such a textured, detailed and colorful vision of the human space-traveling future, and indeed it’s reasonable to assume that Scott conceives of “Prometheus” as a pessimistic counter-argument to James Cameron’s eco-parable on various levels.

Caitlín R. Kiernan:And, lest charges of sexism arise, Kane is the first of the crew "raped" – a man – then Brett – also male – and then the ship's captain, Dallas – also male. Now, turning to charges of sexism in Prometheus (which I am seeing) as regards "rape" by the alien: What? The first person infected is Holloway, who unintentionally impregnates Shaw through consensual sex. Then we see Milburn mouth-fucked by a proto-facehugger. That's two men impregnated (though you might argue Holloway is, rather, infected) to one woman (the presumably male "engineers" not included). So, charges of a sexual bias towards women are simply baseless.

Glenn Kenny:I've said before that I tend to measure certain genre pictures by the number, and quality, of what I call (if you'll excuse the phrase) Holy Crap! Moments. (I don't call them that, exactly, but what I actually call them can't be printed here.) In any event, in the notes I took for this film, on one page, in big block letters taking up pretty much two thirds of the page, I indeed wrote that phrase in the middle of one particular scene. You'll know it when you see it, and it is insane, one of the most perfectly perver

|

| David Smith, untitled |

I have to admit that while plenty of Damien Walter's

"Weird Things" columns at

The Guardian are interesting, and it's really wonderful to see a major newspaper paying regular attention such stuff, and Walter seems like a passionate and thoughtful person ... the latest one, titled,

"Should science fiction and fantasy do more than entertain?" pretty much made me gag. Mostly it was that headline that caused the coughing and sputtering; the piece itself isn't terrible, is well intentioned, and seems primarily aimed at a general audience. I'm not a general audience for the topic, so in my ways, I'm a terrible reader for what Walter wrote. Thus, I'll refrain from comment on the main text.

But there's a statement he made in response to a commenter that didn't make me cough and sputter, it just made me question something I hadn't really questioned before: the term "formalist" and its relationship to criticism within the field of fantasy and science fiction.

In his

comment, Walter stated, "

The Rhetorics of Fantasy is a formalist approach."

I wonder, though. I haven't read

The Rhetorics of Fantasy, so I don't really want to comment on it too much, since my perception is based on reading a few reviews, what some folks have told me, and glancing at the Google Books preview. So it's entirely possible that my question here has nothing to do with that book. I mention it only because it's the book Walter calls "a formalist approach".

What I wonder is how it's possible to have a formalist approach to fantasy or science fiction that is not also perfectly applicable to other sorts of writing. Is there a specifically formalist approach to SF?

To write criticism about SF is almost always to be stuck in content, not form. (We could, and perhaps should, argue about the soft borders between the two terms, the limits of the terms, the fact that content and form don't really exist outside of the words of the text, what that binary hides, etc. — but at the risk of inaccuracy, let's save such an argument for another time.)

There is nothing I can think of at this moment that

formally differentiates SF from not-SF.

The most formalist approach I know of to SF is something like Delany's

The American Shore, and were I to think of a formalist approach to SF, I'd think of Delany, though I think such a term for his work is pretty reductive. It's formalist, yes, often, but seldom only formalist. How and why depends on what we mean by "formalist" and "formalism".

Of course, "formalism" is not a

term that lacks

history or

context or, quite often, an initial capital. Once we get beyond the most linguistically-based sorts

Seventeen years after her last book and ten years after her death, Pauline Kael's name is hard to avoid right now if you read culture magazines or blogs. That's because of three books that came out in October:

The Age of Movies: Selected Writings of Pauline Kael, edited by Sanford Schwartz and published by The Library of America; Brian Kellow's biography

Pauline Kael: A Life in the Dark; and James Wolcott's memoir

Lucking Out: My Life Getting Down and Semi-Dirty in Seventies New York, which includes, apparently, lots of material about his friendship with Kael (before they had a falling-out after he published a sharply critical, even vicious, essay on Kael's acolytes in

Vanity Fair in 1997).

I haven't read Wolcott's memoir, but I've been reading around in Kellow's biography and I'm familiar with almost everything in

The Age of Movies. It was Kael's 1,291-page retrospective collection

For Keeps from 1994 that made me into a fan of her writing when I was an idealistic, ignorant kid studying playwrighting and screenwriting at NYU, and though my opinions about her have changed a bit over the years, she's part of my psyche, her presence inextinguishable, like a crazy aunt.

I hadn't gone back to

For Keeps for a while, probably not since

I wrote about Kael, Susan Sontag, and Craig Seligman's book about them in the fall of 2005. I know a lot more about film history and theory now than I did then, and then I knew more than I did when I first picked up

For Keeps from a library and began to make my way through it. (I also read bookstore copies. I vividly remember sitting on the floor of

Shakespeare & Co. in New York one night and reading through it until the store closed at, I think, midnight. Eventually I got a remaindered copy at

St. Marks Books, the copy I have here beside me now.)

I was a fan of Kael before I knew her name. Until high school, the only movie reviews I'd ever encountered were ones on

Siskel & Ebert. But when I was a freshman in high school, a friend told me about

The New Yorker, which his family read religiously. I started making weekly trips to the library to read it, and it was there that I read these words:

There's nothing affected about Costner's acting or directing. You hear his laid-back, surfer accent; you see his deliberate goofy faints and falls, and all the closeups of his handsomeness. This epic was made by a bland megalomaniac. (The Indians should have named him Plays with Camera.)

That was from one of Kael's last reviews, her December 17, 1990 take on

Dances with Wolves. I almost memorized that review -- enough so that I remember reciting that part of it to my U.S. History class in the fall of 1992 in one of those moments of self-righteous, childish nerditude that defined my adole

Last month I wrote about Joseph Epstein's hilariously grumbly screed against The Cambridge History of the American Novel, and now at Slate the editor of that volume writes a temperate, rational, and utterly ungrumbly response. I particularly liked this paragraph:

Simply recording our appreciation for the "high truth quotient" (the measure Epstein wants) of a stream of canonical novels won't do. It's not clear what that "quotient" is for Epstein, but anything that smacks of pop culture is by definition excluded. Yet novels were and remain a vital part of popular culture, and their emergence in the 18th and 19th centuries was greeted as an affront to the "centurions of high culture" who appointed themselves to guard the gates before Epstein nominated himself for the job. Only a tiny fraction of the hundreds of thousands of American novels published ever achieved—or even aspired to—the exalted status of high art.

From an interview conducted in 1977 by UCLA Ph.D. students with Raymond Durgnat, published in 2006 by Rouge:

DURGNAT: Brigid Brophy said that fundamentally a novel is a take-over bid for one’s ego, and that’s probably true for any work of art. Having an artist’s mind take over one’s own mind in a way that enriches it instead of obliterating it. So temporarily, for an hour and a half, I can become more like Dreyer or more like Minnelli or more like anybody than I could be any other way. The mere effort of adaptation seems to me to be a valuable spiritual exercise; even coming to understand a Fascist mind, for example, via Leni Riefenstahl. In a sense, artists are the priests of alternative minds, that is, of communication. Some artists are so rich one endlessly finds more in them. Or one finds them congenial, like old friends. Others one respects rather than likes. There are works of art which one knows are pretty simple-minded, but a sort of temporary regression is probably good for the soul, in small doses, and provided one doesn’t lower one’s standards about the nature of reality and the value of its reflection in art. [...] It’s in the nature of art to involve criticism, whether moral or social or whatever, because it’s in the nature of things to keep going wrong. That’s not a pessimistic view. Society isn’t one of those machines that can run itself. You seem to find my position confusing, but it’s very simple. I just want to be put inside an interesting mind which is as different as I can bear from my own for two hours. And then come back to being myself by thinking about it. But this implies a variety of response, and why I’m difficult to place is because I appreciate anything that is different and honest; and only in the second place do I ask, ‘Is it of a long term validity? Will I want to keep coming back to it?’

|

| Scarface, 1932 |

There's an interesting

two-part video essay by

Matthias Stork posted at

Press Play about what Stork calls "chaos cinema" -- action movies (mostly from the last 15 years or so) that violate

classical principles of staging, framing, and cutting.

I am in sympathy with Stork's overall point, and one of my few absolutely fuddy-duddy

tendencies is a belief that classical action composition and editing is usually superior to the chaos cinema style Stork identifies -- I often want to yell at directors like

Christopher Nolan (who is five years older than me), "You kids will never understand why

Howard Hawks is great!"

But I have some reservations about Stork's analysis. Basically, they are two: 1.) He interprets an aesthetic technique as a single type of moral expression; 2.) he assumes all audiences watch the way he does.

The first problem is always illegitimate. Not because aesthetics and morality aren't linked -- they often are, as both realms are ones of choice -- but because a technique separated from context has no meaning, moral or otherwise. The types of filming and editing that Stork doesn't like acquire different meanings and purposes in different movies, and Stork's inability to see this blinds him to the vast differences between, for instance, a

Michael Bay explodagasm and

Gamer. Stork has it in his head that a particular way of filming means one thing, and so he's incapable of understanding

Gamer -- he needs to spend some time with

Steve Shaviro. To have filmed

Gamer in a classical style would have changed the film's meaning and ruined much of what is interesting in it, including various effects that could be considered moral or ethical points.

The problem of assuming audiences see, hear, and feel all in the same way is endemic for critics, and may, in fact, be unsolveable -- but a bit of humility helps. Audiences are creative, complex, clever, and contradictory (as some of the more thoughtful comments at the Press Play post show). It is perilous to forget that.

In the second part of his essay, Stork says that chaos cinema is "an aesthetic configuration that refuses to engage viewers mentally and emotionally, i

From the Letters of Note blog, a fascinating letter from Ken Kesey to the New York Times about the theatrical adaptation of his novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (which starred Kirk Douglas):

The answering of one's critics has always struck me as doing about as much good as fighting crabgrass with manure. Critics generally thrive on the knowledge that their barbs are being felt; best to keep silent and starve them of such attention, let them shrivel and dry, spines turned in. So I have tried to keep this silence during the attacks on the Wasserman play of my novel, One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest...figuring that the people who saw the play as being about a mental hospital, because it is set in a mental ward, are the sort that would fault Moby Dick for being an "exaggerated" story about a boat, also figuring that such simplemindedness is relatively harmless. And even keeping silent when the play was condemned because the subject of mental health as a whole was treated disrespectfully, or irresponsibly, or--god forbid!--humorously.

But when the defenders of "Cuckoo's Nest" begin to show signs of suffering some of the same misconceptions as the critics, I feel I must speak out.

Read the whole letter.

Rohan Maltzen writes a memo to Marjorie Gerber about Gerber's new book The Use and Abuse of Literature:

You are caught, I think, in the tension many of us feel between our theoretical commitment to an inclusive approach to literature (some aspects of which you discuss in your chapter on the literary "canon") and our deep appreciation for the aesthetic and intellectual richness of certain texts. As professionals, we have learned that this appreciation is itself conditioned by ideas about what "literature" is and how to measure its greatness. You celebrate close reading and lament a tendency (of which you give no specific examples, which is a problem) for "the historical fact [to take] precedence over the literary work." However, close reading works best—as you glancingly acknowledge when you tie it to Archibald MacLeish's lines "A poem should not mean / But be"�on texts that are verbally complex, ambiguous, and densely metaphorical, rather than ones that work through affect, exposition, even didacticism, texts that address philosophical arguments or social problems rather than turning inward towards language. You praise "the rich allusiveness, deep ambivalence, and powerful slipperiness that is language in action," but once we acknowledge that different standards are also important—once we admit that, say, Elizabeth Gaskell, Felicia Hemans, or Walter Scott (none of whom are particularly ambivalent or slippery) deserve our critical attention as much as Herbert and Donne—we also need to accept other standards, other ways to appreciate and measure a text's significance. Ironically, when you abandon your relativism about what literature is, your anxiety about its reductive "uses" leads you to define it so narrowly that writers who don't think literature is "useless," who use it themselves for clear and potent purposes (what about Pope, or Dickens?) might seem to be ruled out—or against. Pace Keats, not all poets embrace "negative capability," and Henry James is hardly the last word on the relationship between morality and the novel.

.jpeg?picon=3324)

By: Keith Mansfield,

on 1/13/2011

Blog:

Keith Mansfield

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Cinema,

Jonathan Ross,

Werner Herzog,

Ben Dupre,

Brain in a vat,

gallerist,

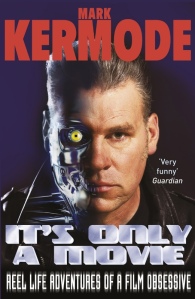

Mark Kermode,

Nick Bostrom,

Simon Mayo,

Treme,

Ultimate Film,

book reviews,

movies,

film,

philosophy,

New Orleans,

autobiography,

Radio,

Angelina Jolie,

America,

critics,

Add a tag

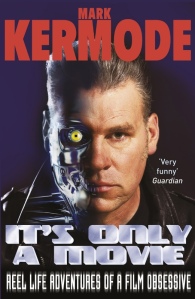

Earlier this week, I found myself wandering the rainwashed streets of New Orleans with U2′s “All I Want is You” playing on the soundtrack in my head. Cut to sitting at the French Quarter’s hippest bar, sipping cocktails mixed by a beautiful actress bartender. Chatting beside me was a local gallerist* and, along from him, a couple of artists he represented. In front of me was the notebook open at the final chapter of Johnny Mackintosh: Battle for Earth and a copy of Mark Kermode’s autobiography, It’s Only a Movie.

Earlier this week, I found myself wandering the rainwashed streets of New Orleans with U2′s “All I Want is You” playing on the soundtrack in my head. Cut to sitting at the French Quarter’s hippest bar, sipping cocktails mixed by a beautiful actress bartender. Chatting beside me was a local gallerist* and, along from him, a couple of artists he represented. In front of me was the notebook open at the final chapter of Johnny Mackintosh: Battle for Earth and a copy of Mark Kermode’s autobiography, It’s Only a Movie.

The gallerist wanted to talk science fiction, notably Iain (M.) Banks and Dr Who. We had similar views on both and I could recount the time where I accidentally got the Scottish novelist a little drunk in a bar before a book reading, buying him whisky and telling him he’d inspired my own novels. It took a little while for the bartender to fess up to being an actress (it turned out a show of hers was even on HBO when I returned to the hotel), but once the fact was divulged she was reciting Shakespearean sonnets and having me recreate a scene from Austin Powers with her. After which I could even tell her how I once worked with Mike Myers!

I know I’m incredibly lucky, but it often feels as though I’m living inside a wonderfully entertaining movie in which I’m director, screenwriter, cinematographer, location manager, head of casting and leading actor. And that’s exactly the conceit of Dr Kermode’s autobiography. It’s already the third book I’ve read this year so I figured it’s time to get busy reviewing or get busy dying. Choose life.

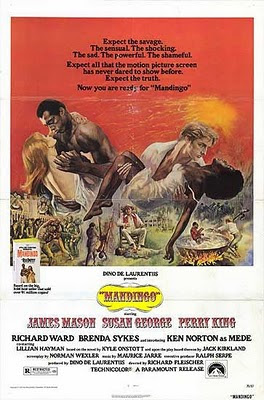

A damn fine bfi book I published with Jonathan Ross

Ever since I noticed there were film critics, Kermode has been my favourite. He’s risen through the ranks to be the nation’s favourite too, with regular slots on The Culture Show and a weekly movie roundup with “clearly the best broadcaster in the country (and having the awards to prove it)” Simon Mayo that’s so entertaining it’s been extended to two whole hours on a Friday afternoon. Possibly the highlight of my time as publisher at the bfi (British Film Institute) was receiving a very lovely email from Dr K. It goes without saying he wrote the bfi Modern Classic on The Exorcist, but this is also the man who made On the Edge of Blade Runner.

Ron Silliman has written an interesting post about, among other things, how he reads:

I’m always reading a dozen books at once, sometimes twice that many. [...] In part, this reading style is because I have an aversion to the immersive experience that is possible with literature. Sometimes, especially if I’m "away" on vacation, I’ll plop down in a deck chair on a porch somewhere with a big stack of books of poetry, ten or twelve at a time, reading maybe up to ten pages in a book, then moving it to a growing stack on the far side of the chair until I’ve gone through the entire pile. Then I start over in the other direction. I can keep myself entertained like this for hours. That is pretty close to my idea of the perfect vacation.

I’ve had this style of reading now for some 50 years – it’s not something I’m too likely to change – but I’ve long realized that this is profoundly not what some people want from their literature, and it’s the polar opposite of the experience of "getting lost" in a summer novel, say. Having been raised, as I was, by a grandmother who had long psychotic episodes makes one wary of the notion of "getting lost" in the fantasy life of another.

(This reminds me of something Alice Munro wrote in the introduction to her

Selected Stories: "I don’t always, or even usually, read stories from beginning to end. I start anywhere and proceed in either direction.")

Hearing how someone else reads can be, for me at least, both exciting and alienating. Exciting because it often explains at least something about their reading taste; alienating because it reminds me what an individual experience reading is. I first encountered this most forcefully when I read Samuel Delany's early essay "About 5,750 Words", in which he presents his own very visual way of interpreting a text as if it is the way everybody reads -- the essay was a revelation to me because I don't build a text in my brain in anything like that method.