In this guest post from the Lee & Low archives, professor Katie Cunningham discusses ways to diversify Common Core recommended texts. As we gather resources to begin the new school year, Katie’s post is a good reminder that each year offers a fresh opportunity to look at the books we use with new eyes to see if they are serving us, and serving our students.

We live in an increasingly diverse society. Nowhere is this more evident than in classrooms, in both urban and suburban schools. Nationally, our classrooms are almost 45% non-White and the trend toward greater diversity is expected to continue. Our classrooms reflect this trend, but our classroom libraries do not. The New York Times found that despite making up about nearly a quarter of the nation’s public school enrollment, young Latino readers seldom see themselves in books. Those of us in schools working with children from minority backgrounds know this to be true as we scan our bookshelves and find protagonists that are overwhelmingly white and living in suburban, privileged settings. The Cooperative Children’s Book Center found that in 2011, only 6% of children’s books featured characters from African American, American Indian, Asian Pacific/ Asian Pacific American, or Latino backgrounds.

Toni Morrison said, “National literature reflects what is on the national mind.” More than ever, we have a responsibility to reflect national population trends through our literature selections. As of 2011, teachers are being directed to the Common Core State Standards and its corresponding Appendix B: Text Exemplars and Performance Tasks, which has suggested texts for read-alouds and independent reading for students at grade level bands K-12.

While not required reading, there remains confusion among teachers and administrators about how to approach the list. As you scan the suggestions, you’ll quickly find a return to traditional texts like Black Stallion in fourth grade and Little Women in sixth through eighth grade. I’m of the opinion that reading traditional texts like the Preamble and Frost’s “The Road Not Taken” (also in Appendix B) can give students cultural capital needed to be successful within the educational system.

Yet, while we can turn to the Standards for suggestions, we need to turn to the children in our own classrooms and ask ourselves whether they see themselves represented in books. Not only a responsibility, this is a moral imperative. We need to ensure a balance between traditional texts and books that offer contemporary portrayals of life and youth today, that reflect the lived experiences of the students in our classrooms.

The Uncommon Corps has started a campaign to better Appendix B and has a running Better B list worthy of checking out to hear what’s on the national mind. Teachers searching for a solution can also consider classic and contemporary multicultural pairings such as those below, especially when searching for titles that represent childhood. If we keep questioning what’s accepted as our national literature for children, we will rightfully start to see books that provide mirrors for every child in every class.

Classic and Contemporary Multicultural Pairings

CLASSIC: Henry and Mudge by Cynthia Rylant

CONTEMPORARY: Auntie Yang’s Great Soybean Picnic by Ginnie Lo; Elizabeti’s Doll by Stephanie Stuve-Bodeen; Loose Tooth by Margaret Yatsevitch Phinney; Bird by Zetta Elliott

CLASSIC: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

CONTEMPORARY: Angel’s Kite by Alberto Bianco; Summer of the Mariposas by Guadalupe Garcia McCall

CLASSIC: Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

CONTEMPORARY: Alicia Afterimage by Lulu Delacre; Cat Girl’s Day Off by Kimberly Pauley

CLASSIC: The Adventures of Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain

CONTEMPORARY: Galaxy Games: The Challengers by Greg Fishbone; Chess Rumble by G. Neri; Yummy: The Last Days of a Southside Shorty by G. Neri

ABOUT KATIE CUNNINGHAM: Guest blogger Katie Cunningham is an Assistant Professor at Manhattanville College. Her teaching and scholarship centers around children’s literature, critical literacy, and supporting teachers to make their classrooms joyful and purposeful. Katie has presented at numerous national conferences and is the editor of The Language and Literacy Spectrum, New York Reading Association’s literacy journal.

ABOUT KATIE CUNNINGHAM: Guest blogger Katie Cunningham is an Assistant Professor at Manhattanville College. Her teaching and scholarship centers around children’s literature, critical literacy, and supporting teachers to make their classrooms joyful and purposeful. Katie has presented at numerous national conferences and is the editor of The Language and Literacy Spectrum, New York Reading Association’s literacy journal.

The Common Core has become a hot-button political issue, but one aspect that’s gone lar gely under the radar is the impact the curriculum will have on students of color, who now make up close to 50% of the student population in the U.S. In this essay, Jane M. Gangi, an associate professor in the Division of Education at Mount Saint Mary College and Nancy Benfer, who teaches literacy and literature at Mount Saint Mary College and is also a fourth-grade teacher, discuss the Common Core’s book choices, why they fall short when it comes to children of color, and how to do better. Originally posted at The Washington Post, this article was reposted with the permission of Jane M. Gangi.

gely under the radar is the impact the curriculum will have on students of color, who now make up close to 50% of the student population in the U.S. In this essay, Jane M. Gangi, an associate professor in the Division of Education at Mount Saint Mary College and Nancy Benfer, who teaches literacy and literature at Mount Saint Mary College and is also a fourth-grade teacher, discuss the Common Core’s book choices, why they fall short when it comes to children of color, and how to do better. Originally posted at The Washington Post, this article was reposted with the permission of Jane M. Gangi.

Children of color and the poor make up more than half the children in the United States. According to the latest census, 16.4 million children (22 percent) live in poverty, and close to 50 percent of country’s children combined are of African American, Hispanic, American Indian, Asian American heritage. When the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) were introduced in 2009—2010 , the literacy needs of half the children in the United States were neglected. Of 171 texts recommended for elementary children in Appendix B of the CCSS, there are only 18 by authors of color, and few books reflect the lives of children of color and the poor.

When the CCSS were open for public comment in 2010, I (Gangi) made that criticism on the CCSS website. My concerns went unacknowledged. In 2012, I presented at a summit on the literacy needs of African American males, Building a Bridge to Literacy for African American Male Youth, held at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. Emily Chiarello from Teaching Tolerance acknowledged the problem and connected me with Student Achievement Partnership, an organization founded by David Coleman and Sue Pimental, “architects” of the English Language Arts standards.

In the fall of 2012, representatives from Student Achievement Partnership came to Mount Saint Mary College in Newburgh, New York, to ask our Collaborative for Equity Literacy Learning (CELL) to help right the wrong. SAP wanted us to provide an amended Appendix B. In July 2013, CELL presented SAP with a list of 150 multicultural titles, which were recommended by educators from across the country and by more than thirty award committees. All the books were annotated and excerpts were provided. The 700+ PowerPoint slides of the project can be found here. SAP then sent the project to Stanford University’s Understanding Language Program for validation of text complexity. The Council of Chief State School Officers has yet to make the addition to the CCSS website.

Why does seeing themselves in books matter to children? Rudine Sims Bishop, professor emerita of The Ohio State University, frames the problem with the metaphor of “mirror” and “window” books. All children need both. Too often children of color and the poor have window books into a mostly white and middle- and-upper-class world.

This is an injustice for two reasons.

One is rooted in the proficient reading research. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, researchers asked, “What do good readers do?” They found that good readers make connections to themselves and their communities. When classroom collections are largely by and about white people, white children have many more opportunities to make connections and become proficient readers. Appendix B of the CCSS as presented added to the aggregate that consistently marginalizes multicultural children’s literature: book lists, school book fairs and book order forms, literacy textbooks (books that teach teachers), and transitional books (books that help children segue from picture books to lengthier texts). If we want all  children to become proficient readers, we must stock classrooms with mirror books for all children. This change in our classroom libraries will also allow children of the dominant culture to see literature about others who look different and live differently.

children to become proficient readers, we must stock classrooms with mirror books for all children. This change in our classroom libraries will also allow children of the dominant culture to see literature about others who look different and live differently.

A second reason we must ensure that all children have mirror books is identity development. For African American children, Rosa Parks and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. are not enough. They must also see African-American artists, writers, political leaders, judges, mathematicians, astronauts, and scientists. The same is true for children of other ethnicities. They must see authors and illustrators who look like them on book jackets. Children must be able to envision possibilities for their futures. And they must fall in love with books. Culturally relevant books help children discover a passion for reading.

I (Benfer) was one of the annotators for the project. Each year I tell my incoming fourth-grade students, “None who enter here remain unchanged” (from Brandon Mull’s Fablehaven). Participating in this project made this statement come true for my students and me. Before working to amend Appendix B, I had been teaching for 16 years, and had always been serious about my classroom library.

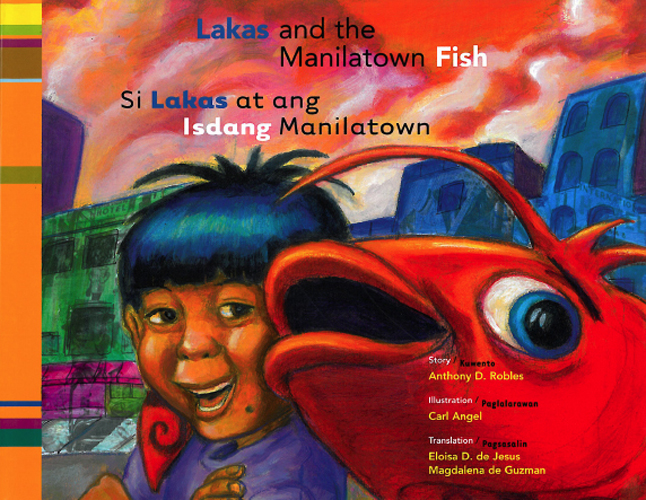

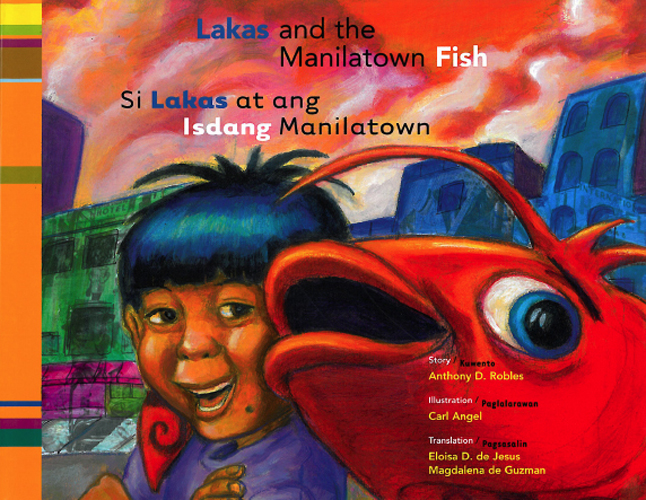

Reading a great book changes us. I had not yet encountered the metaphor of mirrors/windows until hearing Gangi’s talk in our children’s literature course, based on her article “The Unbearable Whiteness of Literacy Instruction.” After the talk I  found myself reflecting on the books to which I was exposing my students. I expanded my library to include many texts reviewed in the project, which allowed my students to see the wonderful diversity in the world. As my classroom library grew, my students began to read and discuss these diverse texts I began to hear students say things like, “I like books which have a black main character,” and parents emailed me to say, “I just wanted to say thank you for acknowledging Black History Month and having such a wonderfully diverse reading library for fourth grade.” Filipino students gave me a standing ovation when I purchased Anthony D. Robles and Carl Angel’s Lakas and the Manilatown Fish/Si Lakas at ang Isdang Manilatow (see Lee & Low Books for this and other multicultural books.)

found myself reflecting on the books to which I was exposing my students. I expanded my library to include many texts reviewed in the project, which allowed my students to see the wonderful diversity in the world. As my classroom library grew, my students began to read and discuss these diverse texts I began to hear students say things like, “I like books which have a black main character,” and parents emailed me to say, “I just wanted to say thank you for acknowledging Black History Month and having such a wonderfully diverse reading library for fourth grade.” Filipino students gave me a standing ovation when I purchased Anthony D. Robles and Carl Angel’s Lakas and the Manilatown Fish/Si Lakas at ang Isdang Manilatow (see Lee & Low Books for this and other multicultural books.)

I recommended Rukhsana Khan’s Wanting Mor, the story of a young girl in Afghanistan to one of my students (see Groundwood Books for this and other multicultural books). This student’s parents were astounded by the change in their daughter. She had been an uninterested reader and was transformed into an enthusiastic one. She began to request copies of books featuring girls in Afghanistan. The students and I spent countless hours creating lists of recommended texts.

What do we do with this issue now, educators? The CCSS have yet to adopt the expanded and enhanced Appendix B, but the message is too important to be filed away. This work must be must shared with educators. The expanded Appendix B contains recommended texts that are mirrors and windows for our students’ worlds.

“None who enter here remain unchanged.” Teaching Tolerance will be publishing the list in the near future. In the meantime, children of the United States are waiting for us to make this change for the better.

Jane M. Gangi is an associate professor in the Division of Education at Mount Saint Mary College in Newburgh, New York. Nancy Benfer teaches literacy and literature at Mount Saint Mary College and is a fourth-grade teacher at Bishop Dunn Memorial School. Gangi is the author of three books: “Encountering Children’s Literature: An Arts Approach,” “Deepening Literacy Learning: Art and Literature Engagements in K-8 Classrooms (with Mary Ann Reilly and Rob Cohen),” and “Genocide in Contemporary Children’s and Young Adult Literature: Cambodia to Darfur.” Both are members of the Collaborative for Equity in Literacy Learning at Mount Saint Mary College. Gangi may be reached at jane.gangi AT msmc.edu; Benfer at nb6221 AT my.msmc.edu.

Filed under:

Common Core State Standards,

Educator Resources Tagged:

CCSS,

common core,

common core standards appendix b

Jaclyn DeForge, our Resident Literacy Expert, began her career teaching first and second grade in the South Bronx, and went on to become a literacy coach and earn her Masters of Science in Teaching. In her column she offers teaching and literacy tips for educators.

Jaclyn DeForge, our Resident Literacy Expert, began her career teaching first and second grade in the South Bronx, and went on to become a literacy coach and earn her Masters of Science in Teaching. In her column she offers teaching and literacy tips for educators.

Earlier this week, I had the pleasure of meeting with a literacy expert who was SUPER involved with the creation of the Common Core Standards (!!!!!), and she gave me some important feedback about the Appendix B supplement I posted last week. To refresh your memory, what we’ve done is compiled a supplement to Appendix B that includes both contemporary literature and authors/characters of color, and that also meets the criteria (complexity, quality, range) used by the authors of the Common Core. We were lucky enough to have this literacy expert take a look at our supplement, and she gave some great suggestions:

- The texts selected for Read Aloud can be outside the text complexity bands for each grade cluster.

- Texts that are Read Aloud in lower grades can be read as Independent Reading in upper grades.

We’ve incorporated these ideas into our Appendix B supplement. So, without further ado, click here for a PDF of our new and improved multicultural supplement to the Common Core’s Appendix B.

Know who else is excited about the updated Appendix B list? This guy:

Further Reading:

What’s in your classroom? Rethinking Common Core recommended texts

Why Window and Mirror Books are Important for All Readers

Filed under:

Curriculum Corner,

Resources Tagged:

appendix b,

Book Lists,

common core standards,

common core standards appendix b,

common core standards ela appendix b,

common core standards language arts appendix b,

diversity,

Educators,

exemplar texts appendix B,

guided reading,

independent reading,

multicultural books,

Read Alouds,

Reading Aloud,

reading comprehension,

smiling dogs

Jaclyn DeForge, our Resident Literacy Expert, began her career teaching first and second grade in the South Bronx, and went on to become a literacy coach and earn her Masters of Science in Teaching. In her column she offers teaching and literacy tips for educators.

Jaclyn DeForge, our Resident Literacy Expert, began her career teaching first and second grade in the South Bronx, and went on to become a literacy coach and earn her Masters of Science in Teaching. In her column she offers teaching and literacy tips for educators.

When the Common Core Standards were created, the authors included a list of titles in Appendix B that exemplified the level of text complexity (found in Appendix A) and inherent quality for reading materials at each grade level. This list was intended as a comparative tool, as a way for teachers and administrators to measure current libraries against country-wide expectations for rigorous literature and informational text. Since its publication, this list, and the titles included and omitted, have created quite a bit of controversy.

Two things are fairly obvious when considering the texts included in Appendix B:

- Most of the titles were first published ages ago.

- Most of the titles are by white people. Or about white people. It’s a pretty white list.

Two things are also fairly important when constructing a classroom library and when selecting texts for instruction:

- Students should have the opportunity to be exposed to both classic and contemporary literature as well as nonfiction texts.

- All students should have the opportunity to see themselves reflected back, as well as to be exposed to cultures and experiences that may differ from their own, in the literature and nonfiction texts we study.

Education Professor Katie Cunningham discussed diversity in Appendix B here on the blog a few weeks ago in her guest post, “What’s in your classroom library? Rethinking Common Core Recommended Texts.” Adding on to her recommendations, I’ve compiled a supplement to Appendix B that includes both contemporary literature and authors/characters of color, but also meets the criteria (complexity, quality, range) used by the authors of the Common Core. Download it here.

If you’re interested in ordering some or all of these titles to supplement your classroom library, please feel free to drop me an email at [email protected]!

What books would you add to Appendix B?

Further Reading:

What’s in your classroom library? Rethinking Common Core Recommended Texts

What is Close Reading?

Filed under:

Curriculum Corner,

Diversity Links,

Resources Tagged:

appendix b,

classroom libraries,

common core standards,

common core standards appendix b,

common core standards ela appendix b,

common core standards language arts appendix b,

guided reading,

Read Alouds,

reading comprehension

ABOUT KATIE CUNNINGHAM: Guest blogger Katie Cunningham is an Assistant Professor at Manhattanville College. Her teaching and scholarship centers around children’s literature, critical literacy, and supporting teachers to make their classrooms joyful and purposeful. Katie has presented at numerous national conferences and is the editor of The Language and Literacy Spectrum, New York Reading Association’s literacy journal.

ABOUT KATIE CUNNINGHAM: Guest blogger Katie Cunningham is an Assistant Professor at Manhattanville College. Her teaching and scholarship centers around children’s literature, critical literacy, and supporting teachers to make their classrooms joyful and purposeful. Katie has presented at numerous national conferences and is the editor of The Language and Literacy Spectrum, New York Reading Association’s literacy journal.

Thanks so much for sharing this information. This article was needed.

Reblogged this on Mixed Diversity Reads Children's Book REviews and commented:

** Children must be able to envision possibilities for their futures. And they must fall in love with books. Culturally relevant books help children discover a passion for reading.**

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, researchers asked, “What do good readers do?” They found that good readers make connections to themselves and their communities. When classroom collections are largely by and about white people, white children have many more opportunities to make connections and become proficient readers. Appendix B of the common core []consistently marginalizes multicultural children’s literature: book lists, school book fairs and book order forms, literacy textbooks (books that teach teachers), and transitional books (books that help children segue from picture books to lengthier texts). [] we must stock classrooms with mirror books for all children. This change in our classroom libraries will also allow children of the dominant culture to see literature about others who look different and live differently.

A second reason we must ensure that all children have mirror books is identity development. They must []see[] artists, writers, political leaders, judges, mathematicians, astronauts, and scientists [that look like them]. They must see authors and illustrators who look like them on book jackets. Children must be able to envision possibilities for their futures. And they must fall in love with books. Culturally relevant books help children discover a passion for reading.

I would make the case that other minorities are in worse shape than the very worthy Black children. Where many other cultures have literature to draw from, including cultures other than Blacks, the Native American child/children have only this country. Even many of the books that are published about Native Americans are written by non-Natives and have gross inaccuracies in both the story and the pictures, when included. Fortunately, many tribes/nations are now publishing their own children’s stories, but these are also not sought or carried by regular children’s book sources. I am not sure how to address this issue, but it certainly should be address by some one with expertise, interest and influence. Eulala Pegram Muscogee Nation

A few days ago I was sitting with young Latina student. We were coloring a glyph to get to know one another. I stated that I would color the eyes brown because my eyes are brown. She wanted blue so they would be like her eyes to which I said, why blue, your eyes aren’t blue. This seven year old looked at me and said, “What color are my eyes?” I looked at her and said, “a beautiful deep brown.” I then asked what color I should make my face. She said light brown and I replied, “good idea.” Then she proceeded to look for a peach crayon for her skin. Needless to say, she is not peach but beautiful reddish brown. She likes fairytales and after our exchange, I told myself I would intermix multicultural fairytales in with the traditional ones so that she will begin to see there is more than Cinderella and Rapunzel.

So, as someone who is embarking on the educator path, thank you for confirming what I know to be true. We need a mirror, a refection of us in this ever-changing world. And we need to train the young to become the ones to ensure those changes are made.