As teachers get ready for school to start in the fall, they might consider a few tips on making students welcome who don’t speak English as a native language. More students speak Spanish as their first language than any other group in the U.S., but there are over a hundred other mother tongues spoken by kids from kindergarten to twelfth grade around this country. No one teacher can possibly know all of these. So, what’s a teacher to do? Two websites offer some practical advice:

http://www2.scholastic.com/browse/article.jsp?id=3747021&FullBreadCrumb=%3Ca+href%3D%22http%3A%2F

and http://www.colorincolorado.org/educators/reachingout/welcoming

There is plenty of research demonstrating that English language learners (or ELLs for short) learn best by drawing on what they already know. That means, they learn best when they start with the language they already speak, their native language (or L1). Children are not blank states when starting kindergarten. This tends to be an unpopular notion in many places, as it was in the Word Geek’s childhood. The idea back in the Olden Days was to punish a child for speaking anything but the “best” meaning the textbook or Standard version of English. The result was, predictably, that kids who didn’t already speak a pretty standard version quit talking altogether in school and made very little progress, then stopped going to school as soon as they could get away with it. This tended to be around the fourth grade (age 8 or 9). Or, because these children struggle to learn math and science in their L2, they get placed in special education classes in which they become bored and disgruntled. This pattern is NOT recommended!

Instead of following this mournful and unsuccessful pattern, consider the tips described by David and Yvonne Freeman at the first site above:

1. Pair a newcomer (an ELL with little or no English) with a partner who speaks his or her L1 as well as some English. Make sure the partner knows this buddy position is a prestigious job and you are very impressed at how well he or she carries it off. The buddy’s job description should include making sure the newcomer knows the class rules, gets the class assignments, and, hopefully, this buddy does some translating.

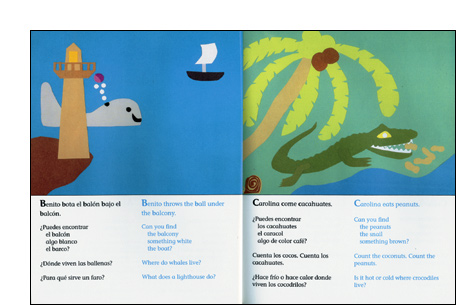

2. Invite a parent volunteer into the classroom to read aloud to the class in the L1 of the newcomer(s). If this involves showing lots of pictures, even the English speakers should get something out of it. Plus, they’ll get some idea of what it’s like to be unable to understand every word of what’s going on – empathy, in other words. Not a bad idea!

3. Let the kids speak in their L1. The Word Geek wishes to put this one up in lights, so she will repeat it in capital letters and add an exclamation mark: LET THE KIDS SPEAK IN THEIR L1! Maybe she should throw some firecrackers in to get some people’s attention here, adding extra exclamation marks for more emphasis. LET THE KIDS SPEAK IN THEIR L1!!!

4. Build a class library in the students’ L1s. It’s especially helpful if some of these books are what we once called “ponies,” in the Olden Days. That means, there is the L1 on one page. On the facing page, the same text is in English. This way, a student sees that his or her native language is respected and supported, and the child can go from the known (L1) to the unknown (L2), with a lot less pain and hassle. The Word Geek was once very fond of such ponies and still has a few in her possession.

5. Organize bilingual tutoring, for example by partnering with a teacher of a class a year or two older than your own, in which there are students who speak the same L1 as your students. These older kids who presumably also speak a little more English can help tutor your students, do a little translating. It’s good for their education and self-esteem as well as helping your students along. A person never learns better than when helping someone else learn.

6. Provide students pen pals, whether in their L1 or L2, and whether through e-mail or by means of old-fashioned pen and paper. Go to the first website above to find a couple of online sites to locate e-mail pen pals. This type of writing is a lot more interesting than writing boring sentences in response to even duller reading exercises.

7. Encourage writing in a journal, whether in the L1 or L2. Sometimes, writing about the acquisition of L2 (namely English) in the L1 is one of the best ways to get a student to think about it after school.

8. Create books of students’ own writings. That is to say, with the computer it is relatively easy to type up things that students write, duplicate them, print them out, and even bind them in inexpensive ways. These can be done in the L1 or L2. “Ponies” created in this way can be distributed to the entire class, giving a newcomer a new feeling of being part of a class, not an outsider. Many of the fonts required to print, say, Vietnamese or Arabic or whatever are already available on the internet for free – or relatively cheaply.

9. Use L1 storytellers to support the ELLs language and culture and share with the rest of the class. The teacher can help bring in the rest of the class by teaching a story ahead of time, or having the class read the story or act it out, if they are too young to read it yet. That way, no one need feel left out when the storyteller comes and speaks another language.

10. Put up the signs that are displayed in the classroom in both English and any L1s spoken by students. This shows that the L1 is valued and, therefore, the student who speaks it is also valued.

Time for an object lesson: When the Word Geek took an introductory linguistics class in college, years ago, the professor told of taking a rabbit in a cage to a first grade classroom. The children in the classroom seemed inordinately quiet and the regular teacher agreed, saying that the kiddies were all “culturally deprived” (using the parlance of the times).

The linguistics professor said that she had a cure for that dread condition. The rabbit was part of it. She put the cage on the teacher’s desk and told the silent students that she and the other teacher had to leave the classroom for a moment. “But I need you kids to help me out,” she told them. “Mr. Bunny will get very, very sick if I go away and nobody talks to him. So, while we’re gone, you need to talk to him and keep talking until I get back. Will you do that for me?”

The kids silently nodded.

The professor and the teacher silently left the classroom. The kids did not see, but the professor had silently started a tape recorder behind the desk.

When the professor got back, as soon as she opened the door of the classroom, the kids were quiet, so she had no idea if her plan had worked. But later, when she played the tape for the teacher, the two adults heard a great cacophony of noise. The whole time the grownups had been out of the room, all the children had been talking to that rabbit, calling him “Mr. Bunny,” telling him not to be scared, letting him know he would be all right. They did not speak perfect Standard English. But they could speak all right and their meaning was clear enough.

Why wouldn’t they talk when their teacher was there? As the professor pointed out to us, when someone gets onto you every time you open your mouth, you stop opening your mouth. So, at the risk of beating a dead horse, LET THE KIDS SPEAK IN THEIR L1. They’ll eventually get to L2 that way. But if they stop talking altogether, they’ll never get anywhere.

This article was written by Diana Gainer, the Word Geek Examiner, on www.examiner.com. Laura Renner added some of her own thoughts as well.

CHCI Launches New Educational Resources for Latino Youth

CHCI Launches New Educational Resources for Latino Youth

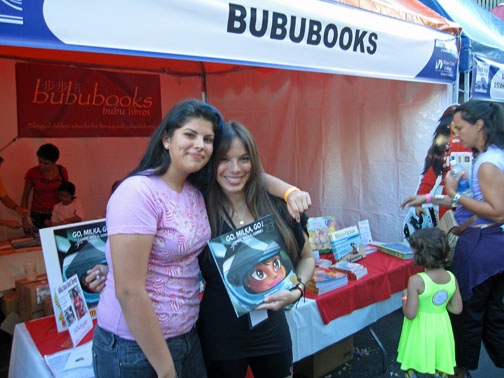

I had never heard of bububooks until I saw this post (reposted) over at jacketflap.com. Looks like you had a great turnout at this event!

I’ll definitely need to get a hold of some of your titles to check out for myself.