new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: barry, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 7 of 7

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: barry in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Alice,

on 8/7/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

mythological creatures,

odyssey,

athena,

the odyssey,

gods,

powell,

slideshow,

barry,

Humanities,

Homer,

Odysseus,

puppeteers,

*Featured,

Images & Slideshows,

Classics & Archaeology,

OUP USA HE,

Barry B. Powell,

OUP USA Higher Ed,

odysseus’s,

charbidis,

Add a tag

The gods and various mythological creatures — from minor gods to nymphs to monsters — play an integral role in Odysseus’s adventures. They may act as puppeteers, guiding or diverting Odysseus’s course; they may act as anchors, keeping Odysseus from journeying home; or they may act as obstacles, such as Cyclops, Scylla and Charbidis, or the Sirens. While Gods like Athena are generally looking out for Odysseus’s best interests, Aeolus, Poseidon, and Helios beg Zeus to punish Odysseus, but because his fate is to return home to Ithaca, many of the Gods simply make his journey more difficult. Below if a brief slideshow of images from Barry B. Powell’s new free verse translation of Homer’s The Odyssey depicting the god and other mythology.

-

Kirkê

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Picture13.png

Kirkê is the goddess of magic, also referred to as a witch or enchantress. Odysseus’ arrival to her island is described as follows, “the house of Kirkê, made of polished stone, in an open meadow. There were wolves around it from the mountains, and lions whom Kirkê had herself enchanted by giving them potions” (10.197-199). When several of Odysseus’ men enter through her doors, she turns them into “beings with the heads of swine, and a pig’s snort and bristles and shape, but their minds remained the same” (10.225-227). However, Odysseus receives assistance from Hermes when he is given a powerful herb that wards off the effect any of Kirke’s potions. Odysseus stays with her for one year, and then decides that he must go back home to Ithaca. As mentioned previously, Kirkê tells him that he must sail to Hades, the realm of the dead, to speak with the spirit of Tiresias.

Kirkê Offering the Cup to Ulysses by John William Waterhouse. 1891. Oil on canvas. Dimensions 149 cm × 92 cm (59 in × 36 in). Gallery Oldham, Oldham.

-

Kalypso

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Picture12.jpg

Shipwrecked from the storm that Zeus conjures up to punish him, Odysseus manages to float over to Ogygia where he encounters the nymph and beautiful goddess Kalypso with whom Odysseus embarks on a seven-year relationship with. She is a nymph, or a nature spirit, who acts as a barrier between Odysseus fulfilling his destiny and returning home to Ithaca. In Book 5, Athena says to Zeus, “he lies on an island suffering terrible pains in the halls of great Kalypso, who holds him against his will. He is not able to come to the land of his fathers” (5.12-14).

Kalypso receiving Telemachos and Mentor in the Grotto detail by William Hamilton. 18th century.

-

Helios

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Picture11.jpg

Odysseus and his men take refuge on the island of Thrinacia (the island of the sun) during their journey. They remain there for a month, but the crew's provisions eventually run out, and Odysseus' crew members slaughter the cattle of the Sun. When the Sun god (Helios) finds out, he asks Zeus to punish Odysseus and his men. Helios demands, “If they do not pay me a suitable recompense for the cattle, I will descend into the house of Hades and shine among the dead!” (12.364-366). Zeus agrees and strikes Odysseus’ ship with lightning and kills all of Odysseus’ crew members.

Head of Helios, middle Hellenistic period. Holes on the periphery of the cranium are for inserting the metal rays of his crown. The characteristic likeness to portraits of Alexander the Great alludes to Lysippan models. Archaeological Museum of Rhodes.

-

Herakles

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Picture10.png

Odysseus and Herakles meet in the Underworld, and also encounters Herakles’ daughter Megara and mother Amphitryon. Odysseus recalls seeing Herakles and says, “Herakles was like the dark night, holding his bare bow and an arrow on the string, glaring dreadfully, a man about to shoot. The baldric around his chest was awesome—a golden strap in which were worked wondrous things, bears and wild boars and lions with flashing eyes, and combats and battles and the murders of men. I would wish that the artist did not make another one like it!” (11.570-576).

Herakles crowned with a laurel wreath, wearing the lion-skin and holding a club and a bow, detail from a scene representing the gathering of the Argonauts. From an Attic red-figure calyx-krater, ca. 460–450 BC. From Orvieto (Volsinii).

-

Ino (Leucothea)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Picture9.jpg

Shipwrecked after Poseidon sinks his ship, Odysseus encounters Ino (Leucothea) who takes pity on him. She leads him toward the land of the Phaeacians and says, “Here, take this immortal veil and tie it beneath your breast. You need not fear you will suffer anything. And when you get hold of the dry land with your hands, untie the veil and throw it into the wine-dark sea, far from land. Then turn away” (5.320-324).

Leucothea (1862), by Jean Jules Allasseur (1818-1903). South façade of the Cour Carrée in the Louvre palace, Paris.

-

Aiolos

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Picture8.jpg

In Book 10, The Achaeans sail from the land of the Cyclops to the home of Aiolus, ruler of the winds. He gifts Odysseus with a bag containing all of the winds in order to guide Odysseus and his crew home. However, the winds escape from the bag due to Odysseus’ men believing that the bag contains gold and silver, and end up bringing Odysseus and his men back to Aiolia. Aiolos provides Odysseus with no further help from then on, as he says, “It is not right that I help or send that man on his way who is hated by the blessed gods” (10.72-73). This is to say that Aiolos judges Odysseus’ return as a bad omen.

This image is a Roman mosaic from the House of Dionysos and the Four Seasons, 3rd century AD, Roman city of Volubilis, capital of the Berber king Juba II (50 BC-24 AD) in the province of Mauretania, Morocco. The Romans loved to decorate their floors with themes taken from Greek myth, and many have survived.

-

Picture7

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Picture7.png

Athena is the most influential goddess, and a catalyst for the events in the story the Odyssey. She is not only the goddess of wisdom, but also of strategy, law and justice, and inspiration among others, and is referred to consistently in the book as “flashing-eyed Athena.” At times in Homer’s epic poem, she acts as a puppeteer throughout Odysseus’ journey as she guides his movements and modifies his and her own appearance to accommodate Odysseus’ circumstances advantageously.

Marble, Roman copy from the 1st century BC/AD after a Greek original of the 4th century BC, attributed to Cephisodotos or Euphranor. Related to the bronze Piraeus Athena.

-

Aphrodite and Ares

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Picture6.jpg

Referred to as the “godlike” visitor, Odysseus is honored during a Phaeacian celebration hosted by Nausicaä’s parents. During the ceremony, a poet named Demdokos plays a song on his lyre, “the love song of Ares and fair-crowned Aphrodite, how they first mingled in love, in secret, in the house of Hephaistos” (8.248-250).

The adultery of Ares and Aphrodite. Clad only in a gown that comes just above her pubic area, Aphrodite holds a mirror while her half-naked lover, Ares, sitting on a nearby bench, embraces her and touches her breast. The device that imprisoned them is visible as a cloth stretched above their heads. Such paintings were especially popular in Roman brothels in Pompeii. Roman fresco from Pompeii, c. AD 60.

-

Artemis

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Picture5.jpg

Approaching the Phaeacian princess Nausicaä for the first time, Odysseus asks, “are you a goddess, or a mortal? If you are a goddess, one of those who inhabit the broad heaven, I would compare you in beauty and stature and form to Artemis, the great daughter of Zeus” (6.139-142).

Wearing an elegant dress and a band about her hair, Artemis carries a torch in her left hand and a dish for drink offerings in her right hand (phialê), not her usual attributes of bow and arrows. She is labeled POTNIAAR, “lady Artemis.” An odd animal, perhaps a young sacrificial bull, gambols at her side. Athenian white-ground lekythos, c. 460-450 BC, from Eretria.

-

Poseidon

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Picture4.jpg

Poseidon holding a trident. Poseidon is the Greek god of the Sea, or as referred to in the epic poem, “the earth-shaker.” The god is long haired and bearded and wears a band around his head. The trident may in origin have been a thunderbolt, but it has been changed into a tuna spear. Corinthian plaque, from Penteskouphia, 550–525 BC. Musée du Louvre, CA 452

-

Hades

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Picture3.png

When Odysseus is on the witch-goddess Kirkê’s island (discussed later), she tells him that he must sail to Hades, the realm of the dead, to speak with the spirit of Tiresias. The underworld is described by Odysseus as a place where “total night is stretched over wretched mortals” (11.18-19). While we do not meet the god Hades directly, his realm is explored by Odysseus. During his time spent in the underworld, Odysseus meets many different people who he had met or been directly influenced by at different points in his life, including his former shipmate Elpenor, his mother Anticleia, and warriors such as Agamemnon, Achilles, Ajax, Minos, Orion, and Heracles.

Hades with Cerberus (Heraklion Archaeological Museum)

-

Hermes

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Picture2.jpg

Hermes weighing souls (psychostasis). In Book 5, Hermes, messenger of the gods, is sent to tell the nymph Kalypso to allow Odysseus to leave so he can return home after several years of being detained on the island of Ogygia. Hermes is also known as the god of boundaries, and as such he is Psychopompos, or “soul-guide”: He leads the souls of the dead to the house of Hades. In a sense, Odysseus is dead, imprisoned on an island in the middle of the sea by Kalypso, the “concealer.” Here the god is shown with winged shoes (in Homer they are “immortal, golden”) and a traveler’s broad-brimmed hat, hanging behind his head from a cord. In his left hand he carries his typical wand, the caduceus, a rod entwined by two copulating snakes. In his right hand he holds a scale with two pans, in each of which is a psychê, a “breath-soul” represented as a miniature man (scarcely visible in the picture). Athenian red-figure amphora from Nola, c. 460 BC, by the Nikon Painter.

-

Zeus

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Picture1.png

Zeus is the ruler of Mount Olympus and all of its inhabitants, and is referred to as “the son of Kronos, god of the dark cloud who rules over everything” in the Odyssey (13.26-27). Though he does not have a predominant role in the Odyssey, his presence is felt as he is the main consulting force of the other deities. He makes an important declaration about the notion of free will in Book 1, and goes on to point out that he sent his messenger Hermes to warn Aigisthos not to kill Agamemnon, but yet the mortal chose not to follow the advice. Zeus says, “And now he has paid the price in full,” in response to Aigisthos’ death. In other words, he believes that the gods can only intervene to a certain degree, but the mortal world has the ultimate control over their own fate.

Statue of a male deity, brought to Louis XIV and restored as a Zeus ca. 1686 by Pierre Granier, who added the arm raising the thunderbolt.

Barry B. Powell is Halls-Bascom Professor of Classics Emeritus at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. His new free verse translation of The Odyssey was published by Oxford University Press in 2014. His translation of The Iliad was published by Oxford University Press in 2013. See previous blog posts from Barry B. Powell.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Gods and mythological creatures of the Odyssey in art appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 7/31/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Music,

james bond,

maryam,

barry,

bond,

*Featured,

john barry,

TV & Film,

Arts & Leisure,

Jon Burlingame,

Maryam d’Abo,

Music of James Bond,

The Living Daylights,

Timothy Dalton,

kara,

daylights,

schönbrunn,

Add a tag

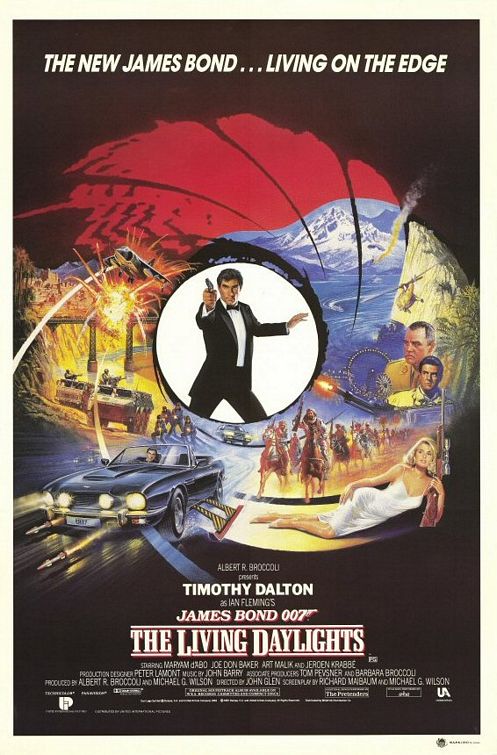

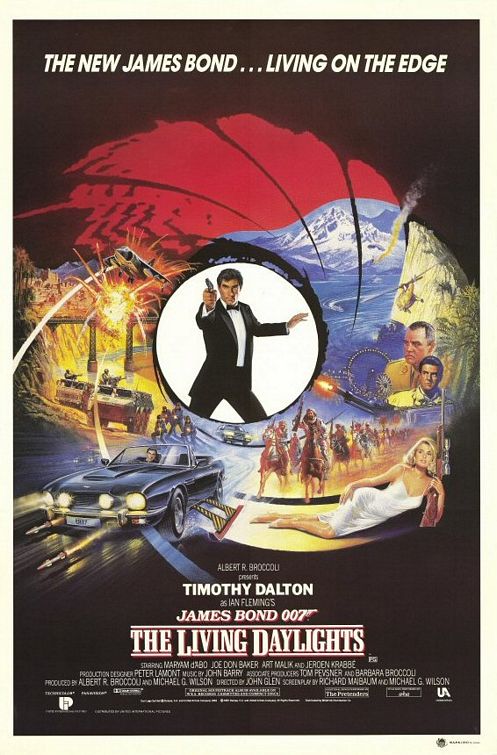

Twenty-seven years ago, on 31 July 1987, James Bond returned to the screen in The Living Daylights, with Timothy Dalton as the new Bond. The film has a notable departure in the style of music, as composer John Barry decided that the film needed a new sound to match this reinvented Bond, and his love interest — a musician with dangerous ties. To celebrate the anniversary, here is a brief extract from The Music of James Bond by John Burlingame.

In the script, Bond is caught up in a complex plot involving high-ranking Soviet intelligence officer Koskov (Jeroen Krabbe) who is supposedly defecting to the West. Koskov’s girlfriend, Czech cellist Kara Milovy (Maryam d’Abo), is duped into helping him escape his KGB guards. A Greek terrorist named Necros (Andreas Wisniewski) then supervises his “abduction” from England and transport to the Tangiers estate of an American arms dealer (Joe Don Baker). Eventually Bond and Kara find themselves at a Soviet airbase in Afghanistan, where they meet a Mujahidin leader (Art Malik) who helps 007 thwart the plot.

Because the early portions of the story take place in Czechoslovakia and Austria, The Living Daylights crew shot for two weeks in Vienna, including all of the scenes where Kara is performing on her cello. Director John Glen recalled conferring with Barry about the classical music that would be heard in the film. “We listened to various pieces before we chose what we were going to use,” Glen said. “Obviously we needed something where the cello was featured strongly.” (They ended up with Mozart, Borodin, Strauss, Dvořák and Tchaikovsky.) They recorded the classical selections with Gert Meditz conducting the Austrian Youth Orchestra and then filmed the ensemble, using the prerecorded music as playback on the set.

Maryam d’Abo was filmed “playing” the cello during several of these scenes. “I started taking private lessons a month prior to the film,” she recalled. “I just learned the movements. They basically soaped the bow so there wasn’t any sound [from the instrument]. It was hard work; I could have done with a couple more weeks of lessons. They demanded a lot of strength. No wonder cellists start when they are eight years old.” The solo parts heard in the film were played by Austrian cellist Stefan Kropfitsch.

The Living Daylights Film Poster (c) MGM

The actress, as Kara, “performs” with the orchestra in several scenes, notably at the end of the film when Barry himself is seen conducting Tchaikovsky’s 1877 Variations on a Rococo Theme and Kara is the soloist. It was filmed on October 15, 1986, at Vienna’s Schönbrunn Palace. Recalled Glen: “It was very unusual for John—unlike a lot of other people who liked to appear in movies, John had never asked before—but on that film, he asked if he could appear. At the time, it struck me as a bit strange. It was almost a premonition that this was going to be his last Bond. I was happy to accommodate him, and he was eminently qualified to do it.”

In fact, Barry had done this once before, appearing on-screen as the conductor of a Madrid orchestra in Bryan Forbes’s Deadfall (1968). On that occasion, he was conducting his own music (a single-movement guitar concerto that was ingeniously written to double as dramatic music for a jewel robbery occurring simultaneously with the concert). This time, he was supposed to be conducting the “Lenin’s People’s Conservatoire Orchestra.”

D’Abo socialized with Barry in London, when the unit was shooting at Pinewood. (She later realized that she had already appeared in two Barry films: Until September and Out of Africa.) “John was there, working on the music,” she said. “He was just a joy to be around. I remember seeing him and having dinner with him and [his wife] Laurie, and John being so excited about writing the music. He was so adorable, saying ‘Your love scenes inspire me to write this romantic music.’ John was such a charmer with women.”

Jon Burlingame is the author of The Music of James Bond, now out in paperback with a new chapter on Skyfall. He is one of the nation’s leading writers on the subject of music for film and television. He writes regularly for Daily Variety and teaches film-music history at the University of Southern California. His other work has included three previous books on film and TV music; articles for other publications including The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, and Premiere and Emmy magazines; and producing radio specials for Los Angeles classical station KUSC.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Barry, Bond, and music on film appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 7/31/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Videos,

culture,

translation,

odyssey,

iliad,

translations,

the odyssey,

powell,

barry,

Humanities,

Homer,

*Featured,

Classics & Archaeology,

OUP USA HE,

Barry B. Powell,

ancient greek art,

a2qbseihmpu,

usm08ae6uzs,

kxiilflbc3a,

Add a tag

Homer’s epic poem The Odyssey recounts the 10-year journey of Odysseus from the fall of Troy to his return home to Ithaca. The story has continued to draw people in since its beginning in an oral tradition, through the first Greek writing and integration into the ancient education system, the numerous translations over the ages, and modern retellings. It has also been adapted to different artistic mediums from depictions on pottery, to scenes in mosaic, to film. We spoke with Barry B. Powell, author of a new free verse translation of The Odyssey, about how the story was embedded into ancient Greek life, why it continues to resonate today, and what translations capture about their contemporary cultures.

Visual representations of The Odyssey and understanding ancient Greek history

Click here to view the embedded video.

Why is The Odyssey still relevant in our modern culture?

Click here to view the embedded video.

On the over 130 translations of The Odyssey into English

Click here to view the embedded video.

Barry B. Powell is Halls-Bascom Professor of Classics Emeritus at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. His new free verse translation of The Odyssey was published by Oxford University Press in 2014. His translation of The Iliad was published by Oxford University Press in 2013. See previous blog posts from Barry B. Powell.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Odyssey in culture, ancient and modern appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 7/17/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

penelope,

slideshow,

Homer,

Odysseus,

*Featured,

Art & Architecture,

Classics & Archaeology,

OUP USA HE,

Barry B. Powell,

OUP USA Higher Ed,

Telemachus,

odyssey,

iliad,

the odyssey,

powell,

barry,

telemachas,

ailos,

nestor,

Books,

Add a tag

Every Ancient Greek knew their names: Odysseus, Penelope, Telemachas, Nestor, Helen, Menelaos, Ajax, Kalypso, Nausicaä, Polyphemos, Ailos… The trials and tribulations of these characters occupied the Greek mind so much that they found their way into ancient art, whether mosaics or ceramics, mirrors or sculpture. From heroic nudity to small visual cues in clothing, we present a brief slideshow of characters that appear in Barry B. Powell’s new free verse translation of The Odyssey.

-

Head of Odysseus

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Picture51.jpg

In the first century BC the Roman emperor Tiberius (42 BC-AD 37) built a villa at Sperlonga between Rome and Naples. There in a grotto sculptors from Rhodes created various scenes from Greek myth, including the blinding of the Cyclops Polyphemos. Fragments of the sculptural group survive, including this evocative head of Odysseus, bearded and wearing a traveler’s cap (pilos), as he plunges a stake into the giant’s eye. Marble, c. AD 20. Museo Archeologico, Sperlonga, Italy; Scala/Ministero per i Beni e le Attività culturali / Art Resource, NY

-

Penelope

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Picture91.jpg

Wearing a modest head cover (what Homer means by “veil”), she is seated on a stone wall, staring pensively at the ground, thinking of her husband. This is a typical posture in artistic representations of Penelope—legs crossed, looking downward, hand to her face (Figures 2.1, 19.1, 20.1). Roman copy (perhaps 1st century BC) of a lost Greek original, c. 460 BC. Museo Pio Clementino, Vatican Museums, Vatican State; Scala / Art Resource, NY

-

Telemachos and Nestor

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Picture14.jpg

Telemachos, holding his helmet in his right hand and two spears in his left, a shield suspended from his arm, greets Nestor. The bent old man supports himself with a knobby staff, and his white hair is partially veiled. Behind him stands his youngest daughter (probably), Polykastê, holding a basket filled with food for the guest. South-Italian wine-mixing bowl, c. 350 BC. Staatliche Museen, Berlin 3289

-

Odysseus and Kalypso

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Picture31.jpg

The goddess presents a box of provisions for the hero’s voyage. The box is tied with a sash. The bearded Odysseus sits on a rock on the shore holding a sword and looking pensive. Athenian red-figure vase, c. 450 BC. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples, Italy; Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

-

Nausicaä and a frightened attendant

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Picture41.jpg

ausicaa on the left holds her ground while one of her ladies runs away with laundry draped about her shoulders (this is the other side of the vase shown in Figure 6.1). Athenian red-figure water-jar from Vulci, Italy, c. 460 BC. Inv. 2322. Staatliche Antikensammlung, Munich, Germany; Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

-

Polyphemos talks to his lead ram

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Picture61.jpg

Blinded, holding his club, leaning against the cave wall, the giant reaches out to stroke his favorite ram under whom Odysseus clings. Athenian black-figure wine cup, c. 500 BC. National Archaeological Museum, Athens 1085

-

Ailos, king of the winds

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Picture71.jpg

Roman mosaic from the House of Dionysos and the Four Seasons, 3rd century AD, Roman city of Volubilis, capital of the Berber King Juba II (50 BC - 24 AD) in the province of Mauretania, Morocco. The Romans loved to decorate their floors with themes taken from Greek myth, and many have survived. Gianni Dagli Orti / The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY

-

Helen and Menelaos

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Picture21.jpg

Menelaos wears a helmet and breast-guard. His right hand is poised on top of a shield while his left, holding a spear, embraces Helen. She wears a cloth cap and a necklace with three pendants and a bangle around her arm. Her cloak slips down beneath her genital area, emphasizing her sexual attractiveness. Decoration on the back of an Etruscan mirror, c. 4th century BC. Townley Collection. Cat. 712. British Museum, London; Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

-

The suicide of Ajax

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Picture81.jpg

The naked hero has fixed his sword in a pile of sand and thrown himself on it. His shield and breastplate are stacked on the left, his club and the scabbard to his sword on the right. His name AIWA is written above him. Athenian red-figure wine-mixing bowl, from Vulci, Italy. British Museum, London, Great Britain; © The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

Barry B. Powell is Halls-Bascom Professor of Classics Emeritus at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. His new free verse translation of The Odyssey was published by Oxford University Press in 2014. His translation of The Iliad was published by Oxford University Press in 2013. See previous blog posts from Barry B. Powell.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Characters of the Odyssey in Ancient Art appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 7/10/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

scenes,

odyssey,

iliad,

the odyssey,

powell,

slideshow,

barry,

Humanities,

Homer,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Art & Architecture,

Images & Slideshows,

Classics & Archaeology,

the iliad,

OUP USA HE,

Barry B. Powell,

ancient greek art,

Ancient Roman Art,

OUP USA Higher Ed,

kylikes,

polyphemus,

Add a tag

The Ancient Greeks were incredibly imaginative and innovative in their depictions of scenes from The Odyssey, painted onto vases, kylikes, wine jugs, or mixing bowls. Many of Homer’s epic scenes can be found on these objects such as the encounter between Odysseus and the Cyclops Polyphemus and the battle with the Suitors. It is clear that in the Greek culture, The Odyssey was an influential and eminent story with memorable scenes that have resonated throughout generations of both classical literature enthusiasts and art aficionados and collectors. We present a brief slideshow of images that appear in Barry B. Powell’s new free verse translation of The Odyssey.

-

Aigisthos kills Agamemnon.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Picture1.jpg

In Book 1, the “father of men and gods,” Zeus, speaks of Aigisthos who the son of Agamemnon had killed. He says, “men suffer pains beyond what is fated through their own folly! See how Aigisthos killed Agamemnon when he came home, though he well knew the end” (1.33-37). In this image, Aigisthos holds Agamemnon, covered by a diaphanous robe, by the hair while he stabs him with a sword. Apparently, this illustration is inspired by the tradition followed in Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, where the king is caught in a web before being killed. Klytaimnestra stands behind Aigisthos, urging him on, while Agamemnon’s daughter attempts to stop the murder (she is called Elektra in Aeschylus’ play). To the far right, a handmaid flees. Athenian red-figure wine-mixing bowl, c. 500-450 BC. Photograph © 2014 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

-

Penelope at her loom with Telemachos.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Picture2.jpg

Telemachos (Odysseus’s son), stands to the left holding two spears, reproaching his mother. She sits mournfully on a chair, anguished by the unknown fate of her husband. Her head is bowed and legs are crossed in a pose canonical for Penelope. Athenian red-figure cup, c. 440 BC, by the Penelope Painter.

-

Telemachos and Nestor.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Picture3.jpg

Telemachos, holding his helmet in his right hand and two spears in his left, a shield suspended from his arm, greets Nestor (the king of Pylos), who has no information about Odysseus. The bent old man supports himself with a knobby staff, and his white hair is partially veiled. Behind him stands his youngest daughter (probably), Polykastê, holding a basket filled with food for the guest. South-Italian red-figure wine-mixing bowl, c. 350 BC.

-

Odysseus and Kalypso.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Picture4.jpg

The goddess presents a box of provisions for the hero’s voyage. The box is tied with a sash. The bearded Odysseus sits on a rock on the shore holding a sword and looking pensive. Athenian red-figure vase, c. 450 BC.

-

Odysseus, Athena, and Nausicaä.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Picture5.jpg

Odysseus asks for the assistance of the Phaeacian princess Nausicaä while she and her handmaidens are bathing by a river. Nausicaa gives Odysseus directions to the palace and advice on how to approach Aretê, queen of the Phaeacians. In this image, the naked Odysseus holds a branch in front of his genitals so as not to startle Nausicaä and her attendants. On the right, near the edge of the picture, Nausicaä half turns but holds her ground. Athena, Odysseus’ protectress, stands between the two figures, her spear pointed to the ground. She wears a helmet and the goatskin fetish (aegis) fringed with snakes as a kind of cape. Clothes hang out to dry on a tree branch (upper left). Athenian red-figure water-jar from Vulci, Italy, c. 460 BC.

-

Maron gives the sack of potent wine to Odysseus.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Picture6.jpg

Books 9 through 12 are told as flashbacks, as Odysseus sits in the palace of the Phaeacians telling the story of his journeys, from Troy, to the land of the Lotus-Eaters, to the land of the Cyclops. Here we see the beardless Kikonian priest Maron give a sack of wine to Odysseus by which Cyclops is overcome. In his left hand, he holds a spear pointed downwards. His crowned wife stands behind him with a horn drinking cup. The very long-haired Odysseus wears high boots, a traveler’s cap (pilos), and holds a spear over his shoulder with his right hand. To the far left stands a Kikonian woman. South Italian red-figure wine-mixing bowl by the Maron Painter, 340-330 BC.

-

Laestrygonians attack Odysseus’ ships.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Picture7.jpg

Without any wind to guide them, the Achaeans row to the land of the Laestrygonians, a race of powerful giants. In this somewhat dim Roman fresco there are ten of Odysseus’ oared ships with single masts in the middle of the narrow bay, three near the shore, half-sunk, and a fourth half-sunk near the high cliffs on the right. Five of the Laestrygonian giants stand on the shore and spear Odysseus’ men or throw down huge rocks. A sixth giant has waded into the water on the left and holds the prow of a ship in his mighty hands. From a house on the Esquiline Hill decorated with scenes from the Odyssey, Rome, c. AD 90.

-

Kirkê enchants the companions of Odysseus.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Picture8.jpg

From there, Odysseus and his men travel to Aeaea, home of the beautiful witch-goddess Kirkê. Shown here is a seductive Kirkê standing naked in the center, stirring a magic drink and offering it to Odysseus’ companions, already turning into animals—the man in front of Kirkê into a boar, the next to the right into a ram, and the third into a wolf. A dog crouches beneath Kirkê’s bowl. The figure behind Kirkê has the head of a boar. On the far left is a lion-man beside whom Odysseus comes with sword drawn (but in the Odyssey they turn only into pigs). On the far right, Eurylochos escapes. Athenian black-figure wine cup, c. 550 BC. Photograph © 2014 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

-

The suitors bring presents.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Picture9.jpg

Penelope sits on a chair at the far right, receiving the suitor’s gifts. The first suitor seems to offer jewelry in a box. The next suitor, carrying a staff, brings woven cloth. The third suitor, also with a staff, carries a precious bowl and turns to speak to the fourth suitor, who brings a bronze mirror. Athenian red-figure vase, c. 470 BC.

-

Death of the suitors.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Picture12.jpg

This is the other side of the cup from Figure 22.1. All the suitors, situated around a dining couch, are in “heroic nudity” but carry cloaks. On the left a suitor tugs at an arrow in his back. In the middle a suitor tries to defend himself with an overturned table. On the right a debonair suitor, with trim mustache, holds up his hands to stop the inevitable. Athenian cup, c. 450-440 BC.

-

Melian relief with the return of Odysseus.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Picture11.jpg

In this “Melian relief” (compare Figure 19.1), Penelope sits on a chair, her legs demurely crossed and her head buried in sorrow. The hatless Odysseus, disguised as a beggar, takes her by the forearm. He is in “heroic nudity” but with a ragged cloak over his arms and back. He holds a staff in his left hand from which his pouch is suspended. Behind Penelope is the beardless Telemachos, and at his feet probably Eumaios the pig herder, seated on the ground and holding a staff, his hat tossed back. The last figure on the left is probably Philoitios, the cow herder from Kephallenia. Terracotta plaque, c. 460-450 BC, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Art Resource, NY.

-

Eurykleia washing Odysseus’ feet.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Picture10.jpg

The old woman, wearing the short hair of a slave, is about to discover the scar on Odysseus leg. The bearded Odysseus, dressed in rags, holds a staff in his right hand and a stick supporting his pouch in his left. He wears an odd traveler’s hat with a bill to shade his eyes. Attic red-figure drinking cup by the Penelope Painter, from Chiusi, c. 440 BC; Museo Archeologico, Chiusi, Italy; Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY.

-

Melian relief with Penelope and Eurykleia.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Picture13.jpg

After the fight against the suitors, Eurykleia tries to persuade Penelope that her husband has returned. Shown here, the mourning Penelope sits in a traditional pose with her hand to her forehead and her legs crossed. Her head is veiled. She stares gloomily downwards, seated on a padded stool beneath which is a basket for yarn. The purpose of these terracotta reliefs, found in different parts of the Roman world, is unclear. Roman Relief, AD 1st century. Museo Nazionale Romano (Terme di Diocleziano), Rome; Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY.

Barry B. Powell is Halls-Bascom Professor of Classics Emeritus at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. His new free verse translation of The Odyssey was published by Oxford University Press in 2014. His translation of The Iliad was published by Oxford University Press in 2013. See previous blog posts from Barry B. Powell.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Scenes from the Odyssey in Ancient Art appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Lauren,

on 2/2/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

Film,

james bond,

oscars,

in memoriam,

composer,

lush,

out of africa,

kathryn,

academy awards,

died,

barry,

best song,

Kathryn Kalinak,

kalinak,

score,

Film Music,

*Featured,

best score,

dances with wolves,

john barry,

symphonic,

goldfinger,

thunderball,

Add a tag

By Kathryn Kalinak

The world of film lost one of the greats on Sunday: composer John Barry. British by birth, he carved a place for himself in Hollywood, winning five Oscars over the course of his career. He cut his teeth on James Bond films – Dr. No, (1962), From Russia With Love (1963), Goldfinger (1964), Thunderball (1965) – and went on to compose seven more. There was something both elegant and hip about these scores, a kind of jazzy sophistication that connoted fast cars, beautiful women, and martinis, shaken not stirred, that is. A jack of all musical trades, he turned to Born Free (1966) and gave it a lush symphonic score and hit song. By 1966, when he won his first Academy Awards (and he won two that year: Best Song and Best Score for Born Free), he became one of the most high profile film composers in the world. He was only 33.

He had an eclectic taste when it came to choosing films – small independent films, huge studio epics, and everything in between – coupled with wide-ranging and versatile compositional skill that could produce a twangy country and western-inspired score for Midnight Cowboy (1969), a jazz-infused score for The Cotton Club (1984), an anxiety-filled score for The Ipcress File (1965), a sensual score for Body Heat (1981), a synthesized score for The Jagged Edge (1985), and a symphonic sound for Out of Africa (1985). He will largely be remembered, though, for those Bond scores – as well he should. They musically define the texture of those films, their time and place, and above all Bond himself with the electric guitar riff that Barry brought to the 007 theme.

But it is the score for Dances With Wolves (1990) that I will remember him for. Like Out of Africa, it is lush, symphonic, melody-laden. But like no other western score that I know of, it manages to avoid the stereotypes for Indians that riddle many of Hollywood’s best western film scores. And I am certainly not the first or the only one to notice this: no tom-tom rhythms, no modal harmonies, no use of fourths and fifths, no dissonance to represent the Sioux

By: Megan,

on 6/17/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

A-Featured,

Meeting,

Leisure,

country,

Jimmie Rodgers,

country music,

roots,

Barry Mazor,

Jimmie,

Rodgers,

Barry,

Mazor,

Add a tag

Megan Branch, Intern

For many people, country music has always been a crossover genre. Artists like Taylor Swift, Reba McEntire and the late Johnny Cash are able to tread the line between  popular and country music, with hits that please the ears of the thirteen-year-old next door and your grandmother. What most people may not know is that Swift, McEntire, Cash and a whole slew of other performers, including Louis Armstrong, owe much of their success to Jimmie Rodgers. In his new book, Meeting Jimmie Rodgers: How America’s Original Roots Music Hero Changed the Pop Sounds of a Century, Barry Mazor chronicles Rodgers’ life and career up until his unfortunate death from tuberculosis at the age of thirty-five. Then Mazor goes on to detail Rodgers’ far-reaching influence that continues even now, almost 80 years since his death. Below, from Meeting Jimmie Rodgers, are 10 of the most interesting things about the father of country music you may not have known.

popular and country music, with hits that please the ears of the thirteen-year-old next door and your grandmother. What most people may not know is that Swift, McEntire, Cash and a whole slew of other performers, including Louis Armstrong, owe much of their success to Jimmie Rodgers. In his new book, Meeting Jimmie Rodgers: How America’s Original Roots Music Hero Changed the Pop Sounds of a Century, Barry Mazor chronicles Rodgers’ life and career up until his unfortunate death from tuberculosis at the age of thirty-five. Then Mazor goes on to detail Rodgers’ far-reaching influence that continues even now, almost 80 years since his death. Below, from Meeting Jimmie Rodgers, are 10 of the most interesting things about the father of country music you may not have known.

1. He ran away from home to join a traveling show:

“By the age of twelve, Jimmie had attempted to stage a tent carnival of his own, and even took it on the road locally […] Soon after, he ran away from home with a medicine show, having convinced the management, based on his amateur ‘experience,’ that he was a professional performer.”

2. He had a voice like no one else:

“…[Y]ou always knew—literally—where he was coming from. The speech from which his singing extended was Mississippi speech, not just in references, but also in sound. On record, his accent is particularly light, sweet, and most of all present—not diluted or eradicated […] he rather charmingly loses a few middle-of-the-word r’s to rhyme a very liquid barrel with gal…”

3. He raised a huge amount of money for the Red Cross during the Depression:

“[Will] Rogers, Rodgers, and crew flew from town to town across Texas and up into Oklahoma, pulling in unprecedented amounts of cash for relief…every dime going to the Red Cross for food and basics like vegetable seeds, so families could stay fed.”

4. BB King is a fan:

“‘My aunt was a kind of collector of music of her time,’ King recalls […] ‘But of the many [records] she had, Jimmie Rodgers was one of my own favorites […] I never tried to yodel—though he was good at that.’”

5. He didn’t stick to only one style of music:

“There would be Peer-produced Jimmie Rodgers recordings featuring Hawaiian bands, jazz bands, country stringbands, pop orchestras, protocowboy and Texas string contingents, and also those groundbreaking sessions with African-American musicians from Louis Armstrong to the Louisville Jug Band.”

6. He inspired many imitators:

“After the unmistakable success of the first blue yodel, ‘T for Texas,’ brazen imitators immediately started to appear, matching the blue yodeling on their records as closely as possible to the original…Many were utterly inconsequential; many only good enough to be recalled in their context…”

7. He made songs his own:

“Slim Bryant recalls how Jimmie changed precisely one line of ‘Mother, the Queen of My Heart,’[…]Jimmie wrote the line ‘I knew I was wrong from the start’ near the end—the whole function of which is to make the storyteller’s own reaction to the story the emotional punch line of the tale.”

8. He had first-hand experience with tragedy:

Songwriter Steve Forbert “focuses on the traumatic winter of 1923 when Jimmie and Carrie’s baby daughter, June Rebecca, died. Jimmie took off for points West for months, then returned to Meridian and received the formal diagnosis of tuberculosis—which, by then, he had surely understood was coming.”

9. He is in our “musical DNA”:

“And while there is no credible evidence that any actual cattle workers had ever yodeled in the moonlight, after Jimmie Rodgers developed this cowboy theme, legions of screen and recording cowboys were going to be doing it until people across the world thought yodeling cowboys were history, not fantasy.”

10. He inspired women, too:

Tanya Tucker, a “famously, singularly, affectingly earthy country heroine—born, it seems in retrospect, to tackle Jimmie Rodgers songs head-on—took the unmitigated yet, as she proved, still timely sentiment of Jimmie’s ‘Daddy and Home’ to the upper reaches of the country charts in 1988, after having fought to make it a single. Tanya Tucker was born in the late ‘50s but had been raised on Rodgers music.”