By Paul Cobb

Recently the jihadist insurgent group formerly known as the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) underwent a re-branding of sorts when one of its leaders, known by the sobriquet Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, was proclaimed caliph by the group’s members. In keeping with the horizonless pretentions that such a title theoretically conveys, the group dropped their geographical focus and embraced a more universalist outlook, settling for the name of the ‘Islamic State’.

As a few observers have noted, the title of caliph comes freighted with a long and complicated history. That history begins in the seventh century AD, when the title was adopted to denote those leaders of the Muslim community who were recognized as the Prophet Muhammad’s “successors”— not prophets themselves of course, but men who were expected, in the Prophet’s absence, to know how to guide the community spiritually as well as politically. Later in the medieval period, classical Islamic political theory sought to carefully define the pool from which caliphs might be drawn and to stipulate specific criteria that a caliph must possess, such as lineage, probity, moral standing and so on. Save for his most ardent followers, Muslims have found al-Baghdadi — with his penchant for Rolex watches and theatrical career reinventions — sorely wanting in such caliphal credentials.

He’s not the only one of course. Over the span of Islamic history, the title of caliph has been adopted by numerous (and sometimes competing) dynasties, rebels, and pretenders. The last ruler to bear the title in any significant way was the Ottoman Abdülmecid II, who lost the title when he was exiled in 1924. And even then it was an honorific supported only by myths of Ottoman legitimacy. But it’s doubtful that al-Baghdadi gives the Ottomans much thought. For he is really tapping into a much more recent dream of reviving the caliphate embraced by various Islamist groups since the early 20th century, who saw it as a precondition for reviving the Muslim community or to combat Western imperialism. Al-Baghdadi’s caliphate is thus a modern confection, despite its medieval trappings.

That an Islamic fundamentalist (to use a contested term of its own) like al-Baghdadi should make an appeal to the past to legitimate himself, and that he should do so without any thoughtful reference to Islamic history, is of course the most banal of observations to make about his activities, or about those of any fundamentalist. And perhaps that is the most interesting point about this episode. For the utterly commonplace nature of examples like al-Baghdadi’s clumsy claim to be caliph suggest that Islamic history today is in danger of becoming irrelevant.

Caliph Abdulmecid II, the last Caliph before Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

This is not because Islamic history has no bearing upon the present Islamic world, but because present-day agendas that make use of that history prefer to cherry-pick, deform, and obliterate the complicated bits to provide easy narratives for their own ends. Al-Baghdadi’s claim, for example, leaps over 1400 years of more nuanced Islamic history in which the institution of the caliphate shaped Muslim lives in diverse ways, and in which regional upstarts had little legitimate claim. But he is hardly alone in avoiding inconvenient truths — contemporary comment on Middle Eastern affairs routinely employs the same strategy.

We can see just such a history-shy approach in coverage of the sectarian conflicts between Shi’i and Sunni Muslims in Iraq, Syria, Bahrain, Pakistan, and elsewhere. The struggle between Sunnis and Shi’ites, we are usually told, has its origins in a contest over religious authority in the seventh century between the partisans of the Prophet’s cousin and son-in-law ‘Ali and those Muslims who believed the incumbent caliphs of the day were better guides and leaders for the community. And so Shi’ites and Sunnis, we are led to believe, have been fighting ever since. It is as if the past fourteen centuries of history, with its record of coexistence, migrations, imperial designs, and nation-building have no part in the matter, to say nothing of the past century or less of authoritarian regimes, identity-politics, and colonial mischief.

We see the inconvenient truths of Islamic history also being ignored in the widespread discourse of crusading and counter-crusading that occasionally infects comment on contemporary conflicts, as if holy war is the default mode for Muslims fighting non-Muslims or vice-versa. When Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi can wrap himself in black robes and proclaim himself Caliph Ibrahim of the Islamic State, when seventh-century conflicts seem like thorough explanations for twenty-first century struggles, or when a terrorist and mass-murderer like the Norwegian Anders Breivik can see himself as a latter-day Knight Templar, then we are sadly living in a world in which the medieval is allowed to seep uncritically into the contemporary as a way to provide easy answers to very complicated problems.

But we should be wary of such easy answers. Syria and Iraq will not be saved by a caliph. And crusaders would have found the motivations of today’s empire-builders sickening. History properly appreciated should instead lead us to acknowledge the specificity, and indeed oddness, of our modern contexts and the complexity of our contemporary motivations. It should, one hopes, lead to that conclusion reached famously by Mark Twain: that history doesn’t repeat itself, even if sometimes it rhymes.

Paul M. Cobb is Chair and Professor of Islamic History in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at the University of Pennsylvania. He is the translator of The Book of Contemplation: Islam and the Crusades and has written a number of other works, most recently The Race for Paradise: An Islamic History of the Crusades.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Caliph Abdulmecid II, by the Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Is Islamic history in danger of becoming irrelevant? appeared first on OUPblog.

The What Everyone Needs to Know (WENTK) series offers a balanced and authoritative primer on complex current event issues and countries. Written by leading authorities in their given fields, in a concise question-and-answer format, inquiring minds soon learn essential knowledge to engage with the issues that matter today. Starting this July, OUPblog will publish a WENTK blog post monthly.

By James Gelvin

ISIS—now just the “Islamic State” (IS)–is the latest incarnation of the jihadi movement in Iraq. The first incarnation of that movement, Tawhid wal-Jihad, was founded in 2003-4 by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. Al-Zarqawi was not an Iraqi: as his name denotes, he came from Zarqa in Jordan. He was responsible for establishing a group affiliated with al-Qaeda in response to the American invasion of Iraq. Over time, this particular group began to evolve as it took on alliances with other jihadi groups, with non-jihadi groups, and as it separated from groups with which it had been aligned. Tawhid wal-Jihad thus evolved into al-Qaeda in Iraq, which had strained relations with “al-Qaeda central.” These strains were caused by the same factors that have created strains between IS and al-Qaeda central. Zarqawi had adopted the tactic of sparking a sectarian war in Iraq by blowing up the Golden Mosque in Samarra, thus instigating Shi’i retaliations against Iraq’s Sunni community, which, in turn, would get mobilized, radicalized, and strike back, joining al-Qaeda’s jihad

What this demonstrates is a long term problem al-Qaeda central has had with its affiliates. Al-Qaeda has always been extraordinarily weak on organization and extraordinarily strong on ideology, which is the glue that holds the organization together.

The ideology of al-Qaeda can be broken down into two parts: First, the Islamic world is at war with a transnational Crusader-Zionist alliance and it is that alliance–the “far enemy”–and not the individual despots who rule the Muslim world–the “near enemy”–which is Islam’s true enemy and which should be the target of al-Qaeda’s jihad. Second, al-Qaeda believes that the state system that has been imposed on the Muslim world was part of a conspiracy hatched by the Crusader-Zionist alliance to keep the Muslim world weak and divided. Therefore, state boundaries are to be ignored.

These two points, then, are the foundation for the al-Qaeda philosophy. It is the philosophy in which Zarqawi believed and it is also the philosophy in which the current head of IS, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, believes as well.

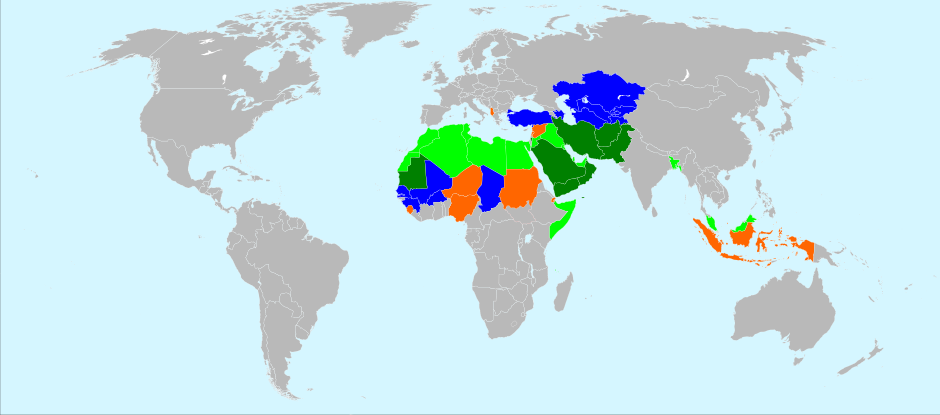

Islamic states (dark green), states where Islam is the official religion (light green), secular states (blue) and other (orange), among countries with Muslim majority. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

We don’t know much about al-Baghdadi. We know his name is a lie–he was not born in Baghdad, as his name denotes, but rather in Samarra. We know he was born in 1971 and has some sort of degree from Baghdad University. We also know he was imprisoned by the Americans in Camp Bucca in Iraq. It may have been there that he was radicalized, or perhaps upon making the acquaintance of al-Zarqawi.

Over time, al-Qaeda in Iraq evolved into the Islamic State of Iraq which, in turn, evolved into the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria. This took place in 2012 when Baghdadi claimed that an already existing al-Qaeda affiliate in Syria, Jabhat al-Nusra, was, in fact, part of his organization. This was unacceptable to the head of Jabhat al-Nusra, Abu Muhammad al-Jawlani. Al-Jawlani took the dispute to Ayman al-Zawahiri who ruled in his favor. Zawahiri declared Jabhat al-Nusra to be the true al-Qaeda affiliate in Syria, ordered al-Baghdadi to return to Iraq, and when al-Baghdadi refused al-Zawahiri severed ties with him and his organization.

There is a certain irony in this, inasmuch as Jabhat al-Nusra does not adhere to the al-Qaeda ideology, which is the only thing that holds the organization together. On the other hand, IS, for the most part does, although al-Qaeda purists believe al-Baghdadi jumped the gun when he declared a caliphate in Syria and Iraq with himself as caliph—a move that is as likely to split the al-Qaeda/jihadi movement as it is to unify it under a single leader. Whereas al-Baghdadi believes there should be no national boundaries dividing Syria and Iraq, al-Jawlani restricts his group’s activities to Syria. Whereas the goals of al-Baghdadi (and al-Qaeda) are much broader than bringing down an individual despot, Jabhat al-Nusra’s goal is the removal of Bashar al-Assad. And whereas al-Baghdadi (and al-Qaeda) believe in a strict, salafist interpretation of Islamic law, Jabhat al-Nusra has taken a much more temperate position in the territories it controls. The enforcement of a strict interpretation of Islamic law–from the veiling of women to the prohibition of alcohol and cigarettes to the use of hudud punishments and even crucifixions—has made IS extremely unpopular wherever it has established itself in Syria.

The recent strategy of IS has been to reestablish a caliphate, starting with the (oil-rich) territory stretching from Raqqa to as far south in Iraq as they can go. This is a strategy evolved out of al-Qaeda first articulated by Abu Musab al-Suri. For al-Suri (who believed 9/11 was a mistake), al-Qaeda’s next step was to create “emirates” in un-policed frontier areas of the Muslim world from which an al-Qaeda affiliate might “vex and exhaust” the enemy. For al-Qaeda, this would be the intermediate step that will eventually lead to a unification of the entire Muslim world. What would happen next was never made clear—Al-Qaeda has always been more definitive about what it is against rather than what it is for.

IS has demonstrated in the recent period that it is capable of dramatic military moves, particularly when it is assisted by professional military officers, such as the former Baathist officers who planned the attack on Mosul. This represents a potential problem for IS: After all, the jailors are unlikely to remain in a coalition with those they jailed after they accomplish an immediate goal. But this is not the limit of IS’s problems. Mao Zedong once wrote that in order to have an effective guerrilla organization you have to “swim like the fish in the sea”–in other words, you have to make yourself popular with the local inhabitants of an area who you wish to control and who are necessary to feed and protect you. Wherever it has taken over, IS has proved itself to be extraordinarily unpopular. The only reason IS was able to move as rapidly as it did was because the Iraqi army simply melted away rather than risking their lives for the immensely unpopular government of Nouri al-Maliki.

However it scored its victory, it should be remembered that taking territory is very different from holding territory. It should also be remembered that by taking and attempting to hold territory in Iraq, ISIS has concentrated itself and set itself up as a target.

IS has other problems as well. It is fighting on multiple fronts. In Syria, it is battling most of the rest of the opposition movement. It is also a surprisingly small organization–8,000-10,000 fighters (although recent victories might enable it to attract new recruits). The Americans used 80,000 troops in its initial invasion of Iraq in 2003 and was still unable to control the country. In addition, we should not forget the ease with which the French ousted similar groups from Timbuktu and other areas in northern Mali last year. As battle-hardened as the press claims them to be, groups like IS are no match for a professional army.

Portions of this article ran in a translated interview on Tasnim News.

James L. Gelvin is a Professor of History at the University of California, Los Angeles. He is the author of The Arab Uprisings: What Everyone Needs to Know, The Modern Middle East: A History and The Israel-Palestine Conflict: One Hundred Years of War.

The What Everyone Needs to Know (WENTK) series offers concise, clear, and balanced primers on the important issues of our time. From politics and religion to science and world history, each book is written by a leading authority in their given field. The clearly laid out question-and-answer format provides a thorough outline, making this acclaimed series essential for readers who want to be in the know on the essential issues of today’s world. Find out what you need to know with OUPblog and the WENTK series every month by RSS or email.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post What is the Islamic state and its prospects? appeared first on OUPblog.