new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: age and ageing, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 10 of 10

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: age and ageing in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Sian Powell,

on 8/19/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

cognitive health,

cognitive reserve,

dementia care,

public health,

dementia prevention,

dementia risk,

education and dementia,

Francisca S. Then,

Journals,

dementia,

*Featured,

age and ageing,

Health & Medicine,

Cognitive Function,

Add a tag

Attaining a higher level of education is considered to be important in order to keep up good cognitive functioning in old age. Moreover, higher education also seems to decrease the risk to develop dementia. This is of high relevance in so far that dementia is a terminal disease characterized by a long degenerative progression with severe impairments in daily functioning. Despite a great amount of research emphasizing the relevance of education, it is not entirely clear how education protects cognitive functioning in old age and how much education is possibly ‘enough’.

The post Years of education may protect against dementia appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Sian Powell,

on 2/20/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

older adults,

Psychology & Neuroscience,

Cognitive Function,

gerentology,

Hayley Wright,

health benefits of sex,

older age,

sexual activity,

Journals,

*Featured,

oxford journals,

age and ageing,

Health & Medicine,

Add a tag

We’ve all heard the phrase “use it or lose it,” and there are many other examples in the media of how we can keep our brains sharp as we age. Research has shown that what is good for your heart is good for your brain, in the biological sense – but what about in a romantic sense?

The post Sex in older age: Can the brain benefit? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/31/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

health,

Journals,

Medical Mondays,

*Featured,

ageing,

oxford journals,

social care,

age and ageing,

alarms,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

catherine henderson,

elderly social care,

telecare,

telehealth,

sensors,

qaly,

demonstrator,

assistive,

Add a tag

By Catherine Henderson

In these times of budgetary constraints and demographic change, we need to find new ways of supporting people to live longer in their own homes. Telecare has been suggested as a useful way forward. Some examples of this technology, such as pull-cord or pendant alarms, have been around for years, but these ‘first-generation’ products have given way to more extensive and sophisticated systems. ‘Second-generation’ products literally have more bells and whistles – for instance, alarms for carbon monoxide and floods, and sensors that can detect movement in and out of bed. These sensors send alerts to a call-centre operator who can organise a response, perhaps call out a designated key-holder, organise a visit to see if there is a problem, or ring the emergency services. There are even more elaborate systems that continuously monitor a person’s activity using sensors and analyse these ‘lifestyle’ data to identify changes in usual activity patterns, but these systems are not in mainstream use. In contrast to telehealth – where the recipient is actively involved in transmitting and in many cases receiving information – the sensors in telecare do not require the active engagement of participants to transmit data, as this is done automatically in the background.

Take-up of telecare remains below its potential in England. One recent study estimated that some 4.17 million over-50 year olds could potentially use telecare, while only about a quarter of that figure were actually using personal alarms or alerting devices. The Department of Health has similarly suggested that millions of people with social care needs and long term conditions could benefit from telecare and telehealth. To help meet this need, it launched the 3-Million Lives campaign in partnership with industry to promote the scaling-up of telehealth and telecare.

The hope held by government and commissioners in the NHS and local authorities is that these new assistive technologies not only promote independence and improve care quality but also reduce the use of health and social care services. To decide how much funding to allocate to these promising new services, these commissioners need a solid evidence base. In 2008, the Department of Health launched the Whole Systems Demonstrator (WSD) programme in three local authority areas in England engaged in whole-systems redesign to test the impacts of telecare (for people with social care needs) and telehealth (for people with long-term conditions).

The research that accompanied the WSD programme was extensive. It included quantitative studies investigating health and social care service use, mortality, costs, and the effectiveness of these technologies. Parallel qualitative studies explored the experiences of people using telecare and telehealth and their carers. The research also examined the ways in which local managers and frontline professionals were introducing the new technologies.

Some results from these streams of research have been published with more to come. From the quantitative research, three articles were published in Age and Ageing over the past year. Steventon and colleagues report on the use of hospital, primary care and social services, and mortality for all participants in the trial – around 2,600 people – based on routinely collected data. Two papers report the results of the WSD telecare questionnaire study (Hirani, Beynon et al. 2013; Henderson, Knapp et al. 2014). The questionnaire study included participants from the main trial who filled out questionnaires about their psychological outcomes, their quality of life, and their use of health and social care services.

The most recent paper to be published in Age and Ageing is the cost-effectiveness analysis of WSD telecare. Participants used a second-generation package of sensors and alarms that was passively and remotely monitored. On average, about five items of telecare equipment were provided to people in the ‘intervention’ group. The whole telecare package accounted for just under 10% of the estimated total yearly health and social care costs of £8,625 (adjusting for case mix) for these people. This was more costly than the care packages of people in the ‘usual care’ group (£7,610 per year) although the difference was not statistically significant. The extra cost of gaining a quality-adjusted life year (QALY) associated with the telecare intervention was £297,000. This is much higher than the threshold range – £20,000 to£30,000 per QALY – used by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) when judging whether an intervention should be used in the NHS (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2008). Given these results, we would, therefore, caution against thinking that second-generation telecare is the cure-all solution for providing good quality care to increasing numbers of people with social care needs while containng costs.

As with any research, it is important to understand how to best use the findings. The telecare tested during the pilot period was ‘second generation’, so conclusions from this research cannot be applied, for instance, to existing pendant alarm systems currently in widespread use. And telecare systems have continued to evolve since this research started. Moreover, while the results summarised here relate to the telecare participants and do not cover any potential impacts on family carers, there is some evidence that telecare alleviates carer strain.

These findings inevitably raise further questions. What are the broader experiences of those using telecare? What makes a telecare experience positive? And what detracts from the experience? Who can benefit most from telecare? Some answers will emerge as we look across all the findings from the WSD research programme. We also need to look forward to findings from new research, such as the current trial of telecare for people with dementia and their carers (Leroi, Woolham et al. 2013). The ‘big’ question is not whether we should implement a ‘one-size fits all’ solution to meet the increasing demands on social care but for whom do these new assistive technologies work best and for whom are they most cost-effective response.

Catherine Henderson is a researcher at the London School of Economics. She is one of the authors of the paper ‘Cost-effectiveness of telecare for people with social care needs: the Whole Systems Demonstrator cluster randomised trial’, which is published in the journal Age and Ageing.

Age and Ageing is an international journal publishing refereed original articles and commissioned reviews on geriatric medicine and gerontology. Its range includes research on ageing and clinical, epidemiological, and psychological aspects of later life.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Senior woman on phone. © bbbrrn, via iStockphoto.

The post What are the costs and impacts of telecare for people who need social care? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/21/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Journals,

exercise,

Medical Mondays,

alzheimer's,

dementia,

physical activity,

*Featured,

oxford journals,

tasks,

age and ageing,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

impairment,

geriatrics,

functional,

Gerontology,

FcTSim,

Lawla Law,

MCI,

mild cognitive impairment,

Add a tag

By Lawla Law

Cognitive impairment is a common problem in older adults, and one which increases in prevalence with age with or without the presence of pathology. Persons with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) have difficulties in daily functioning, especially in complex everyday tasks that rely heavily on memory and reasoning. This imposes a potential impact on the safety and quality of life of the person with MCI as well as increasing the burden on the care-giver and overall society. Individuals with MCI are at high risk of progressing to Alzheimer’s diseases (AD) and other dementias, with a reported conversion rate of up to 60-100% in 5-10 years. These signify the need to identify effective interventions to delay or even revert the disease progression in populations with MCI.

At present, there is no proven or established treatment for MCI although the beneficial effects of physical activity/exercise in improving the cognitive functions of older adults with cognitive impairment or dementia have long been recognized. Exercise regulates different growth factors which facilitate neuroprotection and anti-inflammatory effects on the brain. Studies also found that exercise promotes cerebral blood flow and improves learning. However, recent reviews reported that evidence from the effects of physical activity/exercise on cognition in older adults is still insufficient.

Surprisingly, studies have found that although numerous new neurons can be generated in the adult brain, about half of the newly generated cells in the brain die during the first 1-4 weeks. Nevertheless, research also found that spatial learning or exposure to an enriched environment can rescue the newly generated immature cells and promote their long-term survival and functional connection with other neurons in the adult brain

It has been proposed that exercise in the context of a cognitively challenge environment induces more new neurons and benefits the brain rather than the exercise alone. A combination of mental and physical training may have additive effects on the adult brain, which may further promote cognitive functions.

Daily functional tasks are innately cognitive-demanding and involve components of stretching, strengthening, balance, and endurance as seen in traditional exercise programs. Particularly, visual spatial functional tasks, such as locating a key or finding the way through a familiar or new environment, demand complex cognitive processes and play an important part in everyday living.

In our recent study, a structured functional tasks exercise program, using placing/collection tasks as a means of intervention, was developed to compare its effects on cognitions with a cognitive training program in a population with mild cognitive impairment.

Patients with subjective memory complaint or suspected cognitive impairment were referred by the Department of Medicine and Geriatrics of a public hospital in Hong Kong. Older adults (age 60+) with mild cognitive decline living in the community were eligible for the study if they met the inclusion criteria for MCI. A total of 83 participants were randomized to either a functional task exercise (FcTSim) group (n = 43) or an active cognitive training (AC) group (n = 40) for 10 weeks.

We found that the FcTSim group had significantly higher improvements in general cognitive functions, memory, executive function, functional status, and everyday problem solving ability, compared with the AC group, at post-intervention. In addition, the improvements were sustained during the 6-month follow-up.

Although the functional tasks involved in the FcTSim program are simple placing/collection tasks that most people may do in their everyday life, complex cognitive interplays are required to enable us to see, reach and place the objects to the target positions. Indeed, these goal-directed actions require integration of information (e.g. object identity and spatial orientation) and simultaneous manipulation of the integrated information that demands intensive loads on the attentional and executive resources to achieve the ongoing tasks. It is a matter of fact that misplacing objects are commonly reported in MCI and AD.

Importantly, we need to appreciate that simple daily tasks can be cognitively challenging to persons with cognitive impairment. It is important to firstly educate the participant as well as the carer about the rationale and the goals of practicing the exercise in order to initiate and motivate their participation. Significant family members or caregivers play a vital role in the lives of persons with cognitive impairment, influencing their level of activities and functional interaction in their everyday environment. Once the participants start and experience the challenges in performing the functional tasks exercise, both the participants and the carer can better understand and accept the difficulties a person with cognitive impairment can possibly encounter in his/her everyday life.

Furthermore, we need to aware that the task demands will decrease once the task becomes more automatic through practice. The novelty of the practicing task has to be maintained in order ensure a task demand that allows successful performance and maintain an advantage for the intervention. Novelty can be maintained in an existing task by adding unfamiliar features, and therefore performance of the task will remain challenging and not become subject to automation.

Dr. Lawla Law is a practicing Occupational Therapist for more than 24 years, with extensive experience in acute and community settings in Hong Kong and Tasmania, Australia. She is currently the Head of Occupational Therapy at the Jurong Community Hospital of Jurong Health Services in Singapore and will take up a position as Lecturer in Occupational Therapy at the University of Sunshine Coast, Queensland, Australia in August 2014. Her research interests are in Geriatric Rehabilitations with a special emphasis on assessments and innovative interventions for cognitive impairment. Dr. Law is an author of the paper ‘Effects of functional tasks exercise on older adults with cognitive impairment at risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a randomised controlled trial’, published in the journal Age and Ageing.

Age and Ageing is an international journal publishing refereed original articles and commissioned reviews on geriatric medicine and gerontology. Its range includes research on ageing and clinical, epidemiological, and psychological aspects of later life.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Brain aging. By wildpixel, via iStockphoto.

The post When simple is no longer simple appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/16/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

mental health,

Journals,

Medical Mondays,

happiness,

satisfaction,

*Featured,

ageing,

oxford journals,

age and ageing,

Science & Medicine,

well being,

Health & Medicine,

claire niedzwiedz,

early old age,

life satisfaction,

world map of happiness,

inequalities,

cresh,

creshnews,

bismarckian,

claire_niedz,

niedzwiedz,

health,

Add a tag

By Claire Niedzwiedz

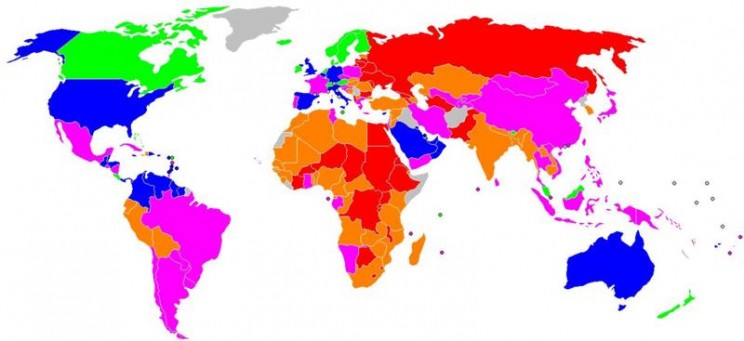

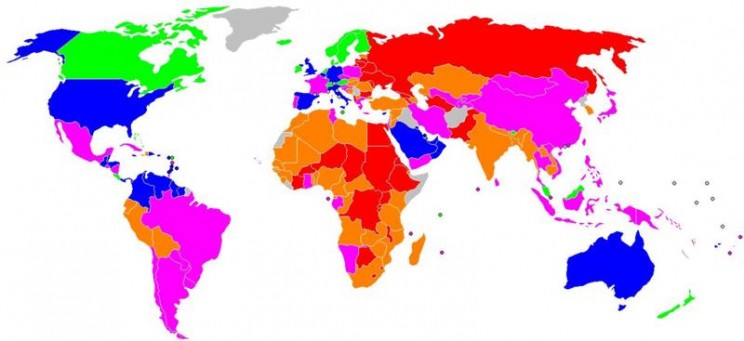

How satisfied are you with your life? The answer is undoubtedly shaped by many factors and one key influence is the country in which you live. Governments across the world are increasingly interested in measuring happiness and well-being to understand how societies are changing, as indicators such as GDP (gross domestic product) do not seem to measure what makes life meaningful. Indeed, some countries, such as Bhutan, have measured national happiness for many years. In the World Map of Happiness below, the countries in green (such as Sweden) have the highest satisfaction. The blue countries are less happy than the green, followed by the pink and orange, and finally the red countries (such as Russia) have the lowest satisfaction. The map conjures up all sorts of interesting questions, like what would the map look like if only older or younger people were included or does happiness vary much within a country?

A U-shaped relationship between age and life satisfaction is often reported, meaning that people are happiest in their 20s and their 60s. But what are the factors that help older people achieve high life satisfaction? Research in this area is particularly important as a result of increasing life expectancy and growth in the proportion of older people. Measuring average well-being is only one side of the story, however. Countries which have high levels of overall life satisfaction may have large inequalities between the richest and poorest in society.

What type of country fosters a more equitable distribution of well-being? This is the focus of our paper recently published in Age and Ageing. We studied the influence of socioeconomic position on life satisfaction in over 17,000 people aged 50 to 75 years old from 13 European countries participating in the Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). To measure socioeconomic position, we used a number of different measures that reflected their position in society at different stages of their life. By looking at their relative position in their own country’s social hierarchy, we created a scale that enabled comparison between countries and across the life course measures. From childhood, we looked at the number of books people reported they had when they were aged 10 years old, a measure of the family’s cultural and economic resources. Education level was used as a measure of early adulthood social position and current wealth was taken as a measure of economic position at the time of the survey. We grouped countries into four categories based on the characteristics of their welfare policy and looked at whether socioeconomic inequalities in life satisfaction varied by the type of welfare state a country fits into.

Intriguingly, we found that Scandinavian (Sweden and Denmark) followed by Bismarckian countries (Germany, Belgium, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Austria, and France) had both higher life satisfaction and narrower differences in well-being between those at the top and bottom of society. Scandinavian countries are traditionally characterised by their high levels of welfare provision, universalism, and the promotion of social equality. Bismarckian countries are characterised by welfare states that maintain existing social divisions in society, in which social security is often related to one’s earnings and administered via the employer. Southern (Greece, Italy, and Spain) and Post-communist (Poland and the Czech Republic) countries, which tend to have less generous welfare states, had lower life satisfaction and larger social inequalities in life satisfaction. The number of books in childhood was a significant predictor of quality of life in early old age in all welfare states, apart from the Scandinavian type, and the relationship was particularly strong among women in the Southern countries. On the whole, however, inequalities in life satisfaction were largest by current wealth across the majority of welfare states.

Our findings have important implications, especially given the welfare policy changes taking place across Europe and the growth in wealth inequalities. It raises questions about how future generations of people are going to experience their early old age. Will average well-being and inequalities between the richest and poorest change as less welfare support is available? What will be the impact of increases in the retirement age? It is clear that these are urgent questions which affect us all and that the policies governments pursue are likely to shape the answers.

Claire Niedzwiedz (@claire_niedz) is a final year doctoral researcher at the University of Glasgow’s Institute of Health and Wellbeing and is part of the Centre for Research on the Environment, Society and Health (CRESH). They tweet at @CRESHnews. She is the author of the paper ‘The association between life course socioeconomic position and life satisfaction in different welfare states: European comparative study of individuals in early old age’, published in the journal Age and Ageing.

Age and Ageing is an international journal publishing refereed original articles and commissioned reviews on geriatric medicine and gerontology. Its range includes research on ageing and clinical, epidemiological, and psychological aspects of later life.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Satisfaction with Life Index Map coloured according to The World Map of Happiness, Adrian White, Analytic Social Psychologist, University of Leicester. Public domain via Wikimedia commons

The post Inequalities in life satisfaction in early old age appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/7/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

NHS,

healthcare,

*Featured,

oxford journals,

age and ageing,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

elderly patients,

health foundation,

hospital management,

older people,

paul harriman,

staff training,

tdcr,

hdcr,

radiographer,

harriman,

Journals,

Medical Mondays,

Add a tag

By Paul Harriman

There is a truism in the world that quality costs, financially. There is a grain of truth in this statement especially if you think in a linear way. In healthcare this has become embedded thinking and any request for increasing quality is met with a counter-request for more money. In a cash-strapped system the lack of available money then results in behaviour that limits improvement. However, as an ex-colleague once said “we have plenty of money, we just choose to spend it in the wrong places”. This implies that if we were to un-spend it in the wrong place we would have plenty of spare cash.

The problem in healthcare, as in most service organisations, is that the system that delivers client value (in this case healthcare to patients) isn’t visible to those working in it. Indeed the only person that see’s the invisible system is the patient receiving that care. Our first task is to make the system visible and we can do this by producing a process map; a series of boxes describing the various activities all linked by one or more arrows. These maps can range from very high level to extremely detailed; the trick is to choose wisely and to look at the process from the patient’s perspective. Having produced your map the next step is to put some data onto it. Once you understand the process you can then start to hypothesise a different way of undertaking the work. Ask yourself;

- would pay your own money for a particular step; if not, then question why it exists

- are the steps in the right order?

- do they require roughly equal amounts of resource

- are there any bottlenecks?

Some four years ago, supported by a grant from the Health Foundation, we started to ask ourselves some of these questions in relation to the delivery of care to frail elderly patients. The answers were, in some cases, completely counter-intuitive. We found that some elderly patients stayed in hospital for many weeks after they could have left. There were many and varied reasons for this but none of them were related to acute hospital care. It was the wider disjointed system with its multiple hand-offs and traditional organisational rules that governed this. It was no-one’s fault, yet it was everyone’s problem.

So like eating the proverbial elephant we decided to start somewhere. It needed an individual clinician to put their hand up and take that first step. That first step was to try something different for one day; if it didn’t work then nothing was lost. The step was tried and the world didn’t end. Instead we found out that changing our normal system of “batching emergency admissions together so that they could all be seen the next day thus maximising consultant efficiency” to “let’s see them as they come in” meant that we reduced the time from arrival to senior specialty review by half. We also found opportunity to remove potential harm.

Having repeated this three times a few other consultants chose to take the trip with us and we repeated the same test over three days. That worked. So we tried for a full week. That also worked. By this time, and we were now almost six months into the journey, a range of staff including consultants, nurses, therapists, ambulance staff, managers and secretaries had all been involved in the tests and had all in their own way contributed to testing the new design and delivery.

The next steps were profound. A suggestion from the clinical director that all the consultants should change their job plans (on the same day) to deliver the new service was met with no dissent. A first in my experience. The physical manifestation of the change, the birth of the Frailty Unit then followed a few weeks later.

What was the cost of this? In terms of real life spend very little. The physical reconfiguration was largely cash neutral. Yes we spent some real money on service improvement support and staff invested their time; in the great scheme of things this was petty cash. But did it really change anything? Some hard metrics showed that we increased the number of patients who were discharged within 48 hrs from 18% to 24% and we reduced the number of total specialty beds by almost a quarter. We didn’t increase our readmissions and our biggest surprise was that we decreased our in-hospital mortality. In softer terms we now see many patients on the day that they arrive; we know how to potentially change our outpatient service and the staff on the Frailty Unit have become masters of caring for Frail Elderly patients.

Involving staff + Improvement science = Better outcomes + Lower Cost

Paul Harriman MBA, TDCR, FETC, HDCR, DCR(R). Paul originally trained as a Diagnostic Radiographer at the Middlesex Hospital qualifying in 1977. He worked in a number of hospitals and obtained his HDCR and TDCR qualifications before coming to Sheffield in 1986. Whilst working as a Superintendent Radiographer at the Royal Hallamshire Hospital, he undertook an MBA and was also selected to join the General Management Scheme. He has since held a number of posts within the Trust working both within clinical directorates and corporate functions.

Paul has major interests in system thinking, improvement science, the use of data for decision making and has been working with Statistical Process Control charts for over 20 years. The main focus of his current work is supporting Geriatric and Stroke Medicine, to understand, analyse and challenge the current work processes. He and Kate Silvester were part of the Flow, Cost, Quality programme sponsored by the Health foundation. He is a co-author of the paper ‘Timely care for frail older people referred to hospital improves efficiency and improves mortality without the need for extra resources‘ for the journal Age and Ageing.

Age and Ageing is an international journal publishing refereed original articles and commissioned reviews on geriatric medicine and gerontology. Its range includes research on ageing and clinical, epidemiological, and psychological aspects of later life.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Blue tone of beds and machines in hospital. By pxhidalgo, via iStockphoto.

The post You can save lives and money appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 1/21/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

depression in old age,

geriatric depression scale,

siegfried weyerer,

weyerer,

incidence,

siegfried,

functional,

health,

Medical Mondays,

depression,

Psychology,

smoking,

senior citizens,

psychiatry,

old age,

dementia,

epidemiology,

eldery,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

ageing,

haas,

oxford journals,

age and ageing,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

impairment,

Add a tag

By Siegfried Weyerer

Depression in old age occurs frequently, places a severe burden on patients and relatives, and increases the utilization of medical services and health care costs. Although the association between age and depression has received considerable attention, very little is known about the incidence of depression among those 75 years of age and older. Studies that treat the group 65+ as one entity are often heavily weighted towards the age group 65-75. Therefore, the prediction of depression in the very old is uncertain, since many community-based studies lack adequate samples over the age of 75.

With the demographic change in the forthcoming decades, more emphasis should be put on epidemiological studies of the older old, since in many countries the increase in this age group will be particularly high. To study the older old is also important, since some crucial risk factors such as bereavement, social isolation, somatic diseases, and functional impairment become more common with increasing age. These factors may exert different effects in the younger old compared to the older old. Knowledge of risk factors is a prerequisite to designing tailored interventions, either to tackle the factors themselves or to define high-risk groups, since depression is treatable in most cases.

With the demographic change in the forthcoming decades, more emphasis should be put on epidemiological studies of the older old, since in many countries the increase in this age group will be particularly high. To study the older old is also important, since some crucial risk factors such as bereavement, social isolation, somatic diseases, and functional impairment become more common with increasing age. These factors may exert different effects in the younger old compared to the older old. Knowledge of risk factors is a prerequisite to designing tailored interventions, either to tackle the factors themselves or to define high-risk groups, since depression is treatable in most cases.

In our recent study, over 3,000 patients recruited by GPs in Germany were assessed by means of structured clinical interviews conducted by trained physicians and psychologists during visits to the participants’ homes. Inclusion criteria for GP patients were an age of 75 years and over, the absence of dementia in the GP’s view, and at least one contact with the GP within the last 12 months. The two follow-up examinations were done, on average, one and a half and then three years after the initial interview.

Depressive symptoms were ascertained using the 15-item version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). We found that the risk for incident depression was significantly higher for subjects

- 85 years and older

- with mobility impairment and vision impairment

- with mild cognitive impairment and subjective memory impairment

- who were current smokers.

It revealed that the incidence of late-life depression in Germany and other industrialized countries is substantial, and neither educational level, marital status, living situation nor presence of chronic diseases contributed to the incidence of depression. Impairments of mobility and vision are much more likely to cause incidents of depression than individual somatic illnesses such as diabetes mellitus and coronary heart disease. As such, it is vital that more attention is paid to the oldest old, functional impairment, cognitive impairment, and smoking, when designing depression prevention programs.

GP practices offers ample opportunity to treat mental health problems such as depression occurring in relation to physical disability. If functional impairment causes greater likelihood of depression, GPs should focus on encouraging older patients to maintain physical health, whether by changing in personal health habits, advocating exercise, correcting or compensating functional deficits by means of medical and surgical treatments, or encouraging use of walking aids. Additionally, cognitive and memory training could prevent the onset of depressive symptoms, as could smoking cessation. If these steps are taken, the burden of old age depression could be significantly reduced.

Siegfried Weyerer is professor of epidemiology at the Central Institute of Mental Health in Mannheim, Germany. He has conducted several national and international studies on the epidemiology of dementia, depression and substance use disorders at different care levels. He is also an expert in health/nursing services research. He is one of the authors of the paper ‘Incidence and predictors of depression in non-demented primary care attenders aged 75 years and older: results from a 3-year follow-up study’, which appears in the journal Age and Ageing. You can read the paper in full here.

Age and Ageing is an international journal publishing refereed original articles and commissioned reviews on geriatric medicine and gerontology. Its range includes research on ageing and clinical, epidemiological, and psychological aspects of later life.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Grief. Photo by Anne de Haas, iStockPhoto.

The post Depression in old age appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Nicola,

on 12/17/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

cardiovascular risk factors,

cognitive decline,

dr alex dregan,

framingham,

older adults,

population study,

risk factors,

vascular disease,

vascular,

cardiovascular,

antihypertensive,

dregan,

smoking,

forgetfulness,

stroke,

public health,

high blood pressure,

cognitive,

cholesterol,

bmi,

epidemiology,

*Featured,

ageing,

oxford journals,

age and ageing,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

forgetful,

Add a tag

By Dr Alex Dregan

Do vascular risk factors such as high blood pressure and smoking make us forgetful?

As our bodies start to show the signs of ageing, our brain is naturally ageing too. But some older people can become forgetful and have trouble remembering common words or organising daily activities more than others. There are few proven interventions to prevent this kind of cognitive decline in older adults, although treating modifiable risk factors for vascular disease and stroke, such as cholesterol and body mass index (BMI), has been suggested as a promising approach to preventing or delaying cognitive impairment for a growing UK population of older adults. So is there a link between high blood pressure and forgetfulness?

Despite much recent interest, studies to date have reported inconsistent relationships between blood pressure and cognitive functioning. Evidence suggests that people diagnosed with high blood pressure levels tend to perform more poorly on most domains of cognitive functioning, including memory, learning, attention, and reasoning. However, clinical trials have so far failed to demonstrate that antihypertensive drugs used to lower or control high blood pressure levels are effective in preventing cognitive decline in older adults. This inconsistent evidence poses a challenge when developing recommendations for the prevention of cognitive ageing.

Cognitive ageing, such as symptoms of forgetfulness, is increasingly seen as the result of the joint effect of several vascular disease risk factors, including high blood pressure, BMI, cholesterol levels, and smoking. However, the combined influence of these on cognitive decline is less commonly explored among older adults at increased risk of both cardiovascular disease and cognitive decline.

In a recent paper, we looked at Framingham stroke and cardiovascular risk scores (a measure used to assess an individual’s probability of developing stroke or cardiovascular disease over a 10-years period) and investigated their association with cognitive decline in older adults. The study included over 8,000 adults aged 50+ living in private households in England. Participants with the highest risk of future stroke or cardiovascular events, based on their risk factors values, were found to perform more poorly on tests of memory and executive functioning after a four year period. This adds weight to the theory that the combined effects of risk factors for vascular disease and stroke may be associated with more rapid cognitive decline in older adults. In other words, those at greater risk of cardiovascular problems were likely to experience a more rapid onset of symptoms associated with cognitive decline, such as forgetfulness.

We believe that these findings support the need for a multifaceted approach when seeking to prevent cognitive decline. The main implication of this is the need for addressing the combined effect of multiple risk factors, including lowering high blood pressure and high cholesterol levels, weight loss, and stopping smoking. Thus, healthcare professionals should encourage older people to adopt healthy lifestyles that would include stopping smoking and increased exercise (as well as improved diet not investigated here) and taking prescribed medicines aimed at controlling high blood pressure and high cholesterol levels. Such recommendations could potentially prevent or delay future declining memory or reasoning capacities in older adults, particularly those in higher risk groups.

The results also suggest that a harmful effect of high blood pressure on memory or reasoning abilities may develop over a prolonged period of time. This may be one reason why short-term trials have failed to show a consistent benefit from antihypertensive treatment on cognitive decline. For instance, since the negative impact of high blood pressure on memory or reasoning abilities takes place over a prolonged period of time, short-term treatment may not be sufficient to reverse or delay its adverse influence. Therefore, we would expect that any potential cognitive benefits from lowering blood pressure may only be observed over substantial periods of time.

These new results suggest that attention to the combined effects of multiple vascular risk factors may hold some promise as a strategy to prevent cognitive decline in older adults.

Dr Alex Dregan is a Lecturer in Translational Epidemiology within the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at the Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Trust and King’s College London. He trained in Public health at the Institute of Education, University of London. His research interests are in translational epidemiology research as applied to public health. He is co-author of the paper Cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive decline in adults aged 50 and over: a population-based cohort study for the Age and Ageing journal, and this has been made freely available for a limited time.

Age and Ageing is an international journal publishing refereed original articles and commissioned reviews on geriatric medicine and gerontology. Its range includes research on ageing and clinical, epidemiological, and psychological aspects of later life.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicines articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The ageing brain appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Nicola,

on 1/26/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

dementia,

delirium,

*Featured,

oxford journals,

age and ageing,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

acute confusional state,

anayo akunne,

cognitive impairment,

health economics,

john young,

lakshmi murthy,

preventing delirium,

interventions,

impairment,

anayo,

akunne,

guideline,

multi,

health,

hospital,

NHS,

prevention,

elderly,

healthcare,

NICE,

Add a tag

By Anayo Akunne

Delirium is a common but serious condition that affects many older people admitted to hospital. It is characterised by disturbed consciousness and changes in cognitive function or perception that develop over a short period of time. This condition is sometimes called “acute confusional state.”

It is associated with poor outcomes. People with delirium have higher chances of developing new dementia, new admission to institutions, extended stays in the hospital, as well as higher risk of death. Delirium also increases the chances of hospital-acquired complications such as falls and pressure ulcers. Poor outcomes resulting from delirium will reduce the patient’s health-related quality of life but also increase the cost of health care.

Delirium can be prevented if dealt with urgently. Enhanced care systems based on multi-component prevention interventions are associated with the potential to prevent new cases of delirium in hospitals. Prevention in a hospital or long-term care setting will lead to the avoidance of costs resulting from patients’ care. For example, the cost of caring for a patient with severe long-term cognitive impairment is high, and prevention of delirium could reduce the number of patients with such impairment. It will therefore reduce the cost of caring for such patients. Prevention could reduce lost life years and loss in health-related quality of life due to other adverse health outcomes associated with delirium.

The multi-component prevention interventions involve making an assessment of people at risk in order to identify and then modify risk factors associated with delirium. Delirium risk factors targeted in such interventions normally include cognitive impairment, sleep deprivation, immobility, visual and hearing impairments, and dehydration. The people at risk of delirium have their risk of delirium reduced through such interventions. The implementation of these interventions is usually done by a trained multi-disciplinary team of health-care staff. This means additional implementation cost. It would therefore be useful to know if this set of prevention interventions would be cost-effective. It was indeed found to be convincingly cost-effective by the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) and was recommended for use in medically ill people admitted to hospital.

It is cost-effective to target multi-component prevention interventions at elderly people at both intermediate and high risk for delirium. It is an attractive intervention to health-care systems. In the United Kingdom the savings for the intervention would spread unevenly between the National Health Service (NHS) and social care providers. The savings to the NHS may be modest and largely accrue through lower costs resulting from reduced hospital stay, whereas the savings to social care are likely to be more considerable resulting from an enduring and diminished burden of dependency and dementia, particularly reduced need for expensive care in long-term care settings. The NHS acute providers may need to invest to implement the intervention and to accrue savings to the wider public sector. The current NHS hospital funding system does not incentivise this type of investment, and this could be a major structural barrier to a widespread uptake of delirium prevention systems of care in the UK.

In the work undertaken as part of the NICE guideline on delirium, the additional cost of implementing the intervention was based on the description of the intervention that required additional staff for delivery. It is possible that the guideline provides an important under-estimate of cost-effectiveness. This is because it might be possible to implement the intervention within existing resources. The intervention is designed to address risk factors for delirium by delivering the sort of person-centred routine c

By: Nicola,

on 12/12/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

health,

elderly,

diabetes,

disability,

mobility,

geriatric,

*Featured,

ageing,

oxford journals,

age and ageing,

diabetic,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

evelien pijpers,

older persons,

recurrent falls,

evelien,

pijpers,

recurrent,

maastricht,

Add a tag

Whilst browsing the Oxford journal Age and Ageing last week, I came across a paper focusing on diabetes in the elderly. Interestingly, it noted that men and women with diabetes aged 65 or over are one and half times more likely to have recurrent falls than people in the same age bracket without diabetes. Having two sets of grandparents in their seventies, one pair with diabetes and one without, I wanted to know about this correlation between diabetes and falling, and how it might apply to them. Here, I speak with Ms. Evelien Pijpers (EP), author of this paper, to learn more. – Nicola (NB)

NB: Your recent paper says that in a three-year study of 1145 Dutch participants aged 65 and over, you discovered an increased risk of recurrent falls associated with diabetes. Can you explain why those with diabetes are more likely to have a fall?

EP: We examined a number of possible contributing factors which led to this increased likelihood of recurrent falls, yet we can only explain about half of the increased risk faced by older patients with diabetes.

The factors which we did link with the increased risk of recurrent falling in patients with diabetes included the use of four or more medications; higher levels of chronic pain, mostly experienced in the muscles and bones; poorer self-perceived health; lower physical activity, grip strength and sense of balance, combined with greater limitations in the performance of daily activities such as bathing and dressing; and more significant problems with cognitive impairment.

Fortunately for the patients, we didn’t record enough major injuries or fractures over the three-year study period to be able to track any correlation between diabetes and fracture risk in older people.

NB: What are the consequences of recurrent falling?

EP: As a geriatrician, I see a lot of mobility problems in older patients. They are present in older people in the accident and emergency department, the hospital wards, and the care and nursing homes. When I visit my older patients at home, it is both the mobility difficulties and the fear of falling which stop them from walking to the shops or strolling through the cobblestone streets of Maastricht.

My older patients with diabetes seem to be especially prone to fall and injure themselves. Even if they avoid lasting injury, I find that afterwards they try and avoid situations in which they could fall again. This unfortunately limits their social contact and the number of physical activities they are willing to undertake, and as such their physical condition declines, sometimes to the point where disability and loss of independence are inevitable. For those with diabetes who are more likely to fall, it is more likely that they will face this quandary.

NB: So what could be done to prevent the increased fall risk in older persons with diabetes?

EP: To improve the quality of life of this growing group of older patients with diabetes, it is important to keep them physically and mentally active, mobile, and able to avoid falls and injuries. Therefore even though we cannot yet account for the entirety of the increased risk of falling, it is possible to address fall risk factors we now know about. A medication review can help, as can muscle training and activities to improve balance – which in turn may even improve pain induced by osteoarthritis. Improving mobility helps individuals to perform everyday activities, and it is easier to feel positive about your health if you are able to maintain independence. It is important that we teach older patients how to fall with the least risk of injury, and how to pick yourself up (both physically and mentally) when you have fallen without losing confidence. As such, physicians should be in the practice of counselling all elderly diabetic patients about active lifestyles and the importance of mobi