The elections, thankfully, are finally over, but America’s search for security and prosperity continues to center on ordinary politics and raw commerce. This ongoing focus is perilous and misconceived. Recalling the ineffably core origins of American philosophy, what we should really be asking these days is the broadly antecedent question: “How can we make the souls of our citizens better?”

To be sure, this is not a scientific question. There is no convincing way in which we could possibly include the concept of “soul” in any meaningfully testable hypotheses or theories. Nonetheless, thinkers from Plato to Freud have understood that science can have substantial intellectual limits, and that sometimes we truly need to look at our problems from the inside.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, the Jesuit philosopher, inquired, in The Phenomenon of Man: “Has science ever troubled to look at the world other than from without?” This not a silly or superficial question. Earlier, Ralph Waldo Emerson, the American Transcendentalist, had written wisely in The Over-Soul: “Even the most exact calculator has no prescience that something incalculable may not balk the next moment.” Moreover, he continued later on in the same classic essay: “Before the revelations of the soul, Time, Space, and Nature shrink away.”

That’s quite a claim. What, precisely, do these “phenomenological” insights suggest about elections and consumerism in the present American Commonwealth? To begin, no matter how much we may claim to teach our children diligently about “democracy” and “freedom,” this nation, whatever its recurrent electoral judgments on individual responsibility, remains mired in imitation. More to the point, whenever we begin our annual excursions to Thanksgiving, all Americans are aggressively reminded of this country’s most emphatically soulless mantra.

“You are what you buy.”

This almost sacred American axiom is reassuringly simple. It’s not complicated. Above all, it signals that every sham can have a patina, that gloss should be taken as truth, and that any discernible seriousness of thought, at least when it is detached from tangible considerations of material profit, is of no conceivably estimable value.

Ultimately, we Americans will need to learn an altogether different mantra. As a composite, we should finally come to understand, every society is basically the sum total of individual souls seeking redemption. For this nation, moreover, the favored path to any such redemption has remained narrowly fashioned by cliché, and announced only in chorus.

Where there dominates a palpable fear of standing apart from prevailing social judgments (social networking?), there can remain no consoling tolerance for intellectual courage, or, as corollary, for any reflective soulfulness. In such circumstances, as in our own present-day American society, this fear quickly transforms citizens into consumers.

While still citizens, our “education” starts early. From the primary grades onward, each and every American is made to understand that conformance and “fitting in” are the reciprocally core components of individual success. Now, the grievously distressing results of such learning are very easy to see, not just in politics, but also in companies, communities, and families.

Above all, these results exhibit a debilitating fusion of democratic politics with an incessant materialism. Or, as once clarified by Emerson himself: “The reliance on Property, including the reliance on governments which protect it, is the want of self-reliance.”

Nonetheless, “We the people” cannot be fooled all of the time. We already know that nation, society, and economy are endangered not only by war, terrorism, and inequality, but also by a steadily deepening ocean of scientifically incalculable loneliness. For us, let us be candid, elections make little core difference. For us, as Americans, happiness remains painfully elusive.

In essence, no matter how hard we may try to discover or rediscover some tiny hints of joy in the world, and some connecting evidence of progress in politics, we still can’t manage to shake loose a gathering sense of paralyzing futility.

Tangibly, of course, some things are getting better. Stock prices have been rising. The economy — “macro,” at least — is improving.

Still, the immutably primal edifice of American prosperity, driven at its deepest levels by our most overwhelming personal insecurities, remains based upon a viscerally mindless dedication to consumption. Ground down daily by the glibly rehearsed babble of politicians and their media interpreters, we the people are no longer motivated by any credible search for dignity or social harmony, but by the dutifully revered buying expectations of patently crude economics.

Can anything be done to escape this hovering pendulum of our own mad clockwork? To answer, we must consider the pertinent facts. These unflattering facts, moreover, are pretty much irrefutable.

For the most part, we Americans now live shamelessly at the lowest common intellectual denominator. Cocooned in this generally ignored societal arithmetic, our proliferating universities are becoming expensive training schools, promising jobs, but less and less of a real education. Openly “branding” themselves in the unappetizing manner of fast food companies and underarm deodorants, these vaunted institutions of higher education correspondingly instruct each student that learning is just a commodity. Commodities, in turn, learns each student, exist solely for profit, for gainful exchange in the ever-widening marketplace.

Optimally, our students exist at the university in order, ultimately, to be bought and sold. Memorize, regurgitate, and “fit in” the ritualized mold, instructs the college. Then, all be praised, all will make money, and all will be well.

But all is not well. In these times, faced with potentially existential threats from Iran, North Korea, and many other conspicuously volatile places, we prefer to distract ourselves from inconvenient truths with the immense clamor of imitative mass society. Obligingly, America now imposes upon its already-breathless people the grotesque cadence of a vast and over-burdened machine. Predictably, the most likely outcome of this rhythmically calculated delirium will be a thoroughly exhausted country, one that is neither democratic, nor free.

Ironically, we Americans inhabit the one society that could have been different. Once, it seems, we still had a unique opportunity to nudge each single individual to become more than a crowd. Once, Ralph Waldo Emerson, the quintessential American philosopher, had described us as a unique people, one motivated by industry and “self-reliance,” and not by anxiety, fear, and a hideously relentless trembling.

America, Emerson had urged, needed to favor “plain living” and “high thinking.” What he likely feared most was a society wherein individual citizens would “measure their esteem of each other by what each has, and not by what each is.”

No distinctly American philosophy could possibly have been more systematically disregarded. Soon, even if we can somehow avoid the unprecedented paroxysms of nuclear war and nuclear terrorism, the swaying of the American ship will become unsustainable. Then, finally, we will be able to make out and understand the phantoms of other once-great ships of state.

Laden with silver and gold, these other vanished “vessels” are already long forgotten. Then, too, we will learn that those starkly overwhelming perils that once sent the works of Homer, Goethe, Milton, and Shakespeare to join the works of more easily forgotten poets are no longer unimaginable. They are already here, in the newspapers.

In spite of our proudly heroic claim to be a nation of “rugged individuals,” it is actually the delirious mass or crowd that shapes us, as a people, as Americans. Look about. Our unbalanced society absolutely bristles with demeaning hucksterism, humiliating allusions, choreographed violence, and utterly endless political equivocations. Surely, we ought finally to assert, there must be something more to this country than its fundamentally meaningless elections, its stupefying music, its growing tastelessness, and its all-too willing surrender to near-epidemic patterns of mob-directed consumption.

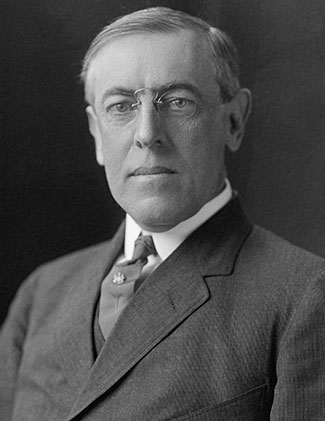

In an 1897 essay titled “On Being Human,” Woodrow Wilson asked plaintively about the authenticity of America. “Is it even open to us,” inquired Wilson, “to choose to be genuine?” This earlier American president had answered “yes,” but only if we would first refuse to stoop so cowardly before corruption, venality, and political double-talk. Otherwise, Wilson had already understood, our entire society would be left bloodless, a skeleton, dead with that rusty death of machinery, more unsightly even than the death of an individual person.

“The crowd,” observed the 19th century Danish philosopher, Søren Kierkegaard, “is untruth.” Today, following recent elections, and approaching another Thanksgiving, America’s democracy continues to flounder upon a cravenly obsequious and still soulless crowd. Before this can change, we Americans will first need to acknowledge that our institutionalized political, social, and economic world has been constructed precariously upon ashes, and that more substantially secure human foundations now require us to regain a dignified identity, as “self-reliant” individual persons, and as thinking public citizens.

Heading image: Boxing Day at the Toronto Eaton Centre by 松林 L. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post After the elections: Thanksgiving, consumerism, and the American soul appeared first on OUPblog.

By Alan McPherson

In 2003, former secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld infamously foresaw victory in Afghanistan and Iraq as demanding a “long, hard slog” and listed a multitude of unanswered questions. Over a decade later, as President Obama (slowly) fulfills his promise to pull all US troops from Afghanistan, a different set of questions emerges. Which Afghans can coalition troops trust to replace them? Will withdrawal lead to even more corruption in the Hamid Karzai government or that of his successor? Has the return of sectarian violence in Iraq been inevitable?

One assumes that the difficulties associated with withdrawing an occupation force are less daunting than those accompanying invasion. Yet the history of US occupations in Latin America demonstrates just the opposite: invasion itself raises the standards of political behavior in invaded countries to stratospheric heights, thus guaranteeing failure and disillusion when the time comes for withdrawal.

A century ago, the Woodrow Wilson administration promised non-intervention in Latin America, but then, in response to World War I, lengthened the already existing US occupation on Nicaragua and started two new occupations, in 1915 in Haiti and in 1916 in the neighboring Dominican Republic.

Publicly, the White House declared that the marines occupied these poor, small republics to protect them from the roaming gunboats of Kaiser Wilhelm.

Much like George W. Bush and his administration did in the Middle East, privately Wilson and his aides shared a vision of a Caribbean area remade in their own image, one where violence as a political tool would be abandoned, political parties would offer programs rather than follow strongmen, and the military would be national and apolitical. Wilson wanted, he said, “orderly processes of just government based upon law.” “The Wilson doctrine is aimed at the professional revolutionists, the corrupting concessionaires, and the corrupt dictators in Latin America,” he added. “It is a bold doctrine and a radical doctrine.”

Too bold and radical, it turned out. At first, failure was not apparent. Marine landings were practically unopposed, as were the overthrows of unfriendly governments. Road building and disarmament moved ahead.

But it was all done without the invaded taking a leadership role, and often against their wishes. There was a great paradox in military occupations teaching democracy. “It is typically American,” one marine later mused, “to believe we can exert a subtle alchemy by our presence among a people for a few years which will eradicate the teaching and training of hundreds of years . . . It is a hopeful theory, but it lacks common sense.” One Haitian advanced that “we have now less knowledge of self-government than we had in 1915 because we have lost the practice of making our own decisions.” A group of Haitians agreed, “there is only one school of self-government, it is the practice of self-government.”

The withdrawal of troops, therefore, became a long, hard slog out. Marines began the process only reluctantly when the invaded became so vocal that they compelled the State Department to eschew plans for reform and just order the troops out. In Nicaragua and Haiti, massacres of or by US troops helped trigger withdrawal. Dominicans rejected all US proposals for withdrawal until they included the return to power of strongmen.

As withdrawal neared, signs were everywhere that the invaded had absorbed no lessons from invaders. Incompetence, discord, and violence plagued elections. New regimes fired competent bureaucrats and appointed friends and family members to office. In Nicaragua, hacks from enemy parties filled the ranks of the constabulary.

Haitians were equally divided between black and mixed-race office-seekers, between north and south, between elites and masses. One US commissioner called Haitian peasants “immeasurably superior to the so-called elite here who affect to despise them and propose to despoil them.” Yet, pressured by public opinion, he cut deals with the worst political elites as marines abandoned plans for creating a responsible middle class in Haiti.

Marines also found themselves in a paradox as they championed nationalism so as to minimize anti-U.S. sentiment. In Nicaragua, occupiers banned any political talk or any flying of partisan flags in the constabulary. They marched guards twice a day with the blue and white Nicaraguan flag and had them sing the national anthem as they raised and lowered it. This was “a ceremony new to a country that for years has known no loyalties except to clan or party.”

US policymakers often threw up their hands as they pulled out troops. Of disoccupying Veracruz, which he also invaded in 1914, Wilson sighed, “If the Mexicans want to raise hell, let them raise hell. We have nothing to do with it. It is their government, it is their hell.”

“It is more difficult to terminate an intervention than to start one,” later observed diplomat Dana Munro, a lesson learned after years of wasted effort in Latin America. US policymakers in the Middle East would do well to take it to heart and avoid leaving the invaded rudderless in their hell.

Alan McPherson is a professor of international and area studies at the University of Oklahoma and the author of The Invaded: How Latin Americans and their Allies Fought and Ended US Occupations.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The long, hard slog out of military occupation appeared first on OUPblog.

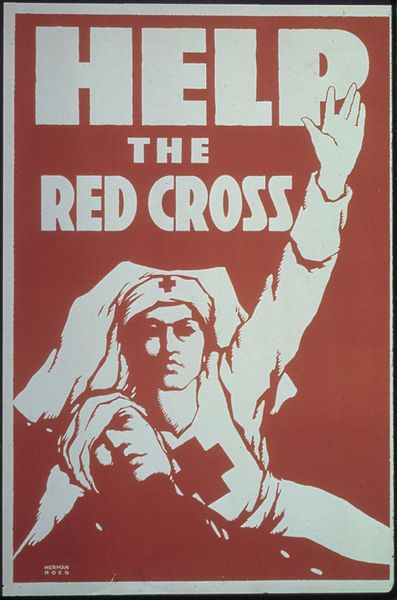

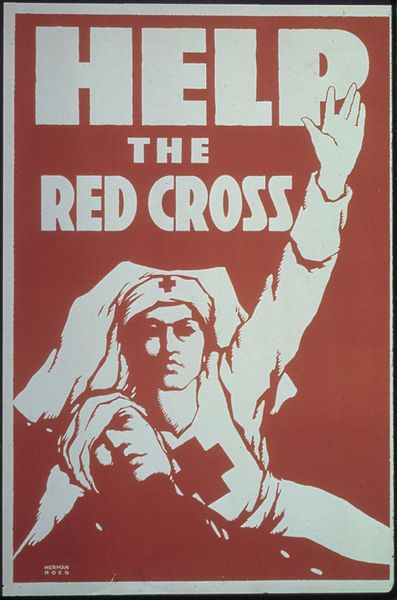

By Julia F. Irwin

President Barack Obama has proclaimed March 2014 as “American Red Cross Month,” following a tradition started by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1943. 2014 also marks the 100-year anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War in Europe. Although the United States would not officially enter the war until 1917, the American Red Cross (ARC) became deeply involved in the conflict from its earliest days. Throughout World War I and its aftermath, the ARC and its volunteers carried out a wide array of humanitarian activities, intended to alleviate the suffering of soldiers and civilians alike.

In honor of American Red Cross Month, and in commemoration of the First World War’s centennial, here’s a list of things you might not have known about the World War I era history of the American Red Cross:

In honor of American Red Cross Month, and in commemoration of the First World War’s centennial, here’s a list of things you might not have known about the World War I era history of the American Red Cross:

(1) On 12 September 1914, just over a month after the First World War erupted in Europe, the American Red Cross sent its first relief ship to the continent. Christened the Red Cross, the ship carried units of physicians and nurses, surgical equipment, and hospital supplies to seven warring European nations. This medical aid reached soldiers on both sides of the conflict.

(2) After the United States entered World War I in April 1917, the ARC’s intervention in Europe expanded enormously. Over the next several years, the ARC’s leaders established humanitarian activities in roughly two-dozen countries in Europe and the Near East. The organization provided emergency food and medical relief on the battlefields and on the European home front, but ARC staff and volunteers also took on more constructive projects. They built hospitals, health clinics and dispensaries, libraries, playgrounds, and orphanages. They organized public health campaigns against diseases like typhus and tuberculosis. They took steps to reform sanitation in many countries and introduced nursing schools in several major cities. The ARC’s efforts for Europe, in other words, went well beyond immediate material relief to include long-term, comprehensive social welfare projects.

(3) During World War I, the American Red Cross experienced astronomical growth. On the eve of war, ARC membership hovered around 10,000 US citizens. By 1918, the last year of the war, roughly 22 million adults and 11 million children – approximately 1/3 of the total US population at that time – had joined the American Red Cross and contributed at least $1.00 to the organization.

(4) In 1917, the wartime leaders of the American Red Cross established an auxiliary body for US children—the Junior Red Cross (JRC). During the war, American Juniors put on plays and organized bazaars to raise money for the war effort, collected scrap metal and other essential war supplies, and helped produce over 371,500,000 relief articles for US and Allied soldiers and refugees, valued at nearly $94,000,000. After the war ended, postwar leaders transformed the JRC’s mission, moving away from relief efforts and towards international education initiatives. They established pen-pal programs for between US and European schoolchildren and published monthly magazines to teach US students about the culture, geography, and histories of other nations.

(4) In 1917, the wartime leaders of the American Red Cross established an auxiliary body for US children—the Junior Red Cross (JRC). During the war, American Juniors put on plays and organized bazaars to raise money for the war effort, collected scrap metal and other essential war supplies, and helped produce over 371,500,000 relief articles for US and Allied soldiers and refugees, valued at nearly $94,000,000. After the war ended, postwar leaders transformed the JRC’s mission, moving away from relief efforts and towards international education initiatives. They established pen-pal programs for between US and European schoolchildren and published monthly magazines to teach US students about the culture, geography, and histories of other nations.

(5) As President of the United States, President Woodrow Wilson was also the President of the American Red Cross. Wilson proved to be a tireless promoter of the ARC. Through many speeches and press releases, he urged all US citizens to join the ARC, defining this as nothing less than a patriotic duty. Wilson also lent his face to ARC posters, magazine covers, and other forms of fundraising publicity. It was on 18 May 1918, perhaps, that Wilson made his commitment to the ARC most visible: on that day, he led a 70,000-person American Red Cross parade down Fifth Avenue in New York City. The visible support of Wilson and his administration played a critical role in defining the ARC as the United States’ leading humanitarian organization—a status that it continues to hold 100 years later.

Julia F. Irwin is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of South Florida. She specializes in the history of US relations with the 20th century world, with a particular focus on the role of humanitarianism in US foreign affairs. She is the author of Making the World Safe: The American Red Cross and a Nation’s Humanitarian Awakening. Her current research focuses on the history of US responses to global natural disasters.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) “Help the Red Cross.” Public domain via U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (2) “In the Name of Mercy – Give.” Albert Herter. Public domain via Library of Congress.

The post The American Red Cross in World War I appeared first on OUPblog.

In honor of American Red Cross Month, and in commemoration of the First World War’s centennial, here’s a list of things you might not have known about the World War I era history of the American Red Cross:

In honor of American Red Cross Month, and in commemoration of the First World War’s centennial, here’s a list of things you might not have known about the World War I era history of the American Red Cross: (4) In 1917, the wartime leaders of the American Red Cross established an auxiliary body for US children—the Junior Red Cross (JRC). During the war, American Juniors put on plays and organized bazaars to raise money for the war effort, collected scrap metal and other essential war supplies, and helped produce over 371,500,000 relief articles for US and Allied soldiers and refugees, valued at nearly $94,000,000. After the war ended, postwar leaders transformed the JRC’s mission, moving away from relief efforts and towards international education initiatives. They established pen-pal programs for between US and European schoolchildren and published monthly magazines to teach US students about the culture, geography, and histories of other nations.

(4) In 1917, the wartime leaders of the American Red Cross established an auxiliary body for US children—the Junior Red Cross (JRC). During the war, American Juniors put on plays and organized bazaars to raise money for the war effort, collected scrap metal and other essential war supplies, and helped produce over 371,500,000 relief articles for US and Allied soldiers and refugees, valued at nearly $94,000,000. After the war ended, postwar leaders transformed the JRC’s mission, moving away from relief efforts and towards international education initiatives. They established pen-pal programs for between US and European schoolchildren and published monthly magazines to teach US students about the culture, geography, and histories of other nations.