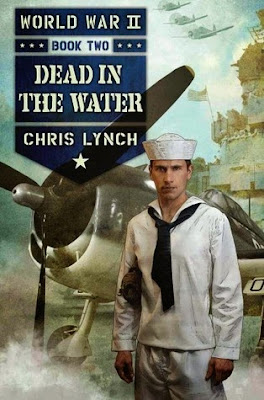

Hank and Theo McCallum are about as close as brothers can be, so when it looks like war is inevitable, their plan is to enlist in the navy together. That way, they can look out for each other. Except their father isn't having any of that - his thinking is that it would only take one torpedo to kill both his sons. Before they even leave the house to enlist, it Hank for the navy, Theo for….the Army Air Corps.

A few weeks later, Hank and Theo are off to the Navy and Army, and it isn't long after boot camp that Hank finds himself on the aircraft carrier USS

Yorktown, heading to the Pacific Ocean after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. On board the

Yorktown, Hank is an airedale, which means his duties are plane-handling on the flight deck, doing everything except flying the aircraft he takes care of. But Hank also has a reputation for always wanting to throw a little ball. Before the Navy, Hank and Theo were all about baseball, and when they left for the war, Theo gave his well-used glove to Hank. Now, with two gloves and a ball, Hank was always looking for someone to throw with during down time.

Once in the Pacific, the

Yorktown doesn't see any real action until after a visit to Pearl Harbor. Seeing the aftermath of the attack there, however, finally makes the war real for Hank, but he has absolute faith that the US will win. Meantime, he meets a throwing partner, who actually has a few baseball tricks he can teach Hank, who is pretty good himself. Mess Attendant First Class Bradford had played in the Negro Leagues before the war, but now he is generally stuck below deck, serving the pilots, sleeping far down in the ship, even below the torpedoes, because of the Navy's policy of racial segregation.

Hank and Bradford soon become friends and throwing buddies, often joined by two of the pilots whose planes Hank services whenever they fly missions. At first, the

Yorktown and its partner ship the

Lexington still don't see much action, but a bad attack on the ships causes the

Lexington to sink and the

Yorktown to have to limp back to Pearl Harbor for repairs.

With time on their hands, Hank, Bradford and their two pilot friends decide to head to Waikiki Beach, even though Bradford isn't allowed to be there because he is African American. When two policemen try to get them to leave, they refuse and they prevail.

Soon the

Yorktown is really to sail again, headed for Midway Island and a life and death battle with the Japanese. Once again, the Yorktown is hit, and sinks. Can Hank survive a sinking ship?

Dead in the Water is narrated by Hank and although he and Theo are close, we don't really ever know how Theo is doing. This is Hank's story (Theo is book 3). Lynch always manages to make his narrators so believable and so historically real sounding, and Hank is no different. He has a real 1940s way of speaking. My only complaint is that there is too much baseball involved. On the other hand, Lynch doesn't overdo it on the military stuff, including combat details. There's just enough description and not too, too detailed on that front.

At first, I was afraid that taking on the racism that black sailors faced in the Navy (in fact, in all the Armed Forces in WWII), might be a bit over the top in a book like this, but it really works and he manages to make his points quite nicely, the beach incident is packed with tension. I did find it a little surprising that Hank, baseball obsessed as he is, never heard of the Negro Leagues, and the Newark Eagles, for which Bradford played.

Dead in the Water is the third Chris Lynch book I've read, and I have to be honest and say they have all been very good. The story flows nicely, they are historically correct, and most important to me, Lynch doesn't glorify war.

And, of course, now I am curious to know what happened to Hank and his friends.

This book is recommended for readers age 11+

This book was an EARC received from

NetGalley

When the United States went to war in 1941, a lot of people immediately signed up to serve their country. After all, they were Americans and their country was now in peril. And so millions of Americans went to war to fight to defend the freedoms they enjoyed so much. African Americans signed up to defend their country as well, but things weren't quite the same for them. Instead of receiving the honor and respect they deserved, African Americans faced the same discrimination and segregation in the armed forces that they had lived with in civilian life. And, naturally, they were given the lowest jobs available. In the Navy, that usually meant serving in the mess as a cook or being on permanent clean up detail.

But in 1943, the Navy sent a group of African Americans to Port Chicago in northern California. There, they loaded huge cargoes of ammunition onto waiting ships. The men immediately noticed that only African Americans were doing this potentially dangerous job, although they had to be supervised by white Naval officers, since the Navy didn't have an black officers.

Then, on July 17, 1944 at 10:18 PM, as a second shift of men were loading the ammunition, an explosion occurred that was felt for miles around and which killed 320 men instantly. Among that number were 202 African Americans. At first, everyone thought the explosion was an enemy attack, but they soon realized what had happened.

A few weeks after being moved to another port, the surviving men were ordered back to loading ammunition. Afraid of what had happened to their friends at Port Chicago, 258 African American sailors refused to obey the order. In fact, they were willing to obey any other order, but that one. After being told to pack their gear, they were crowded onto a prison barge. Eventually, most of the men would return to their jobs. In the end, 50 sailors would be charged with mutiny and court marshaled. And in the trial that followed, they would be found guilty, even though it was clear that the trial was biased, the judge taking the word of the white officers over that of the black sailors.

NAACP lawyer Thurgood Marshall watched the trial closely and when the guilty verdict was announced, immediately started preparing an appeal. And though the appeal was not successful, the 50 sailors were eventually returned to active service, though they carried the stigma of mutiny throughout their lives.

And yet, Steven Sheinkin contends, these 50 sailors did more for changing the civil rights of African Americans serving their country than they are given credit for, eventually helping to remove the practice of discrimination and segregation in ALL branches of the armed services.

Sheinkin has done it again. First with

Bomb: the Race to Build - and Steal - the World's Most Dangerous Weapon, now with

The Port Chicago 50: Disaster, Mutiny and the Fight for Civil Rights. The moment I started reading it, I couldn't put it down. Sheinkin has once again written an exciting nonfiction narrative about a little know part of American history. In

The Port Chicago 50, he brings to life many of the men involved, especially Joe Small, whom the Navy considered to be the ringleader of the mutiny. You will meet other unforgettable men in this book, some heroic, some a bit scoundrelly. But they will all rivet you to their story.

As with all good nonfiction, there are plenty of photographs throughout the book, along with the names of each of the 50 sailors listed in the front matter. Back matter includes extensive source notes, as well as works cited, a list of oral histories and documentaries used and the records of the U.S. Navy regarding the Port Chicago explosion and subsequent trial.

The Port Chicago 50 is a well written, well documented addition to the history of African Americans, their history of the Navy and the history of Civil Rights and a book not to be missed.

This book is recommended for readers age 12+

This book was borrowed from the NYPL

Last month U.S. Navy Secretary Ray Mabus confirmed while visiting a shipyard in San Diego's Barrio Logan that a new replenishment ship will be named the USNS Cesar Chavez. You all know Cesar Chavez, what he did and what he stood for, no matter whether you agreed with it all or not.

Last month U.S. Navy Secretary Ray Mabus confirmed while visiting a shipyard in San Diego's Barrio Logan that a new replenishment ship will be named the USNS Cesar Chavez. You all know Cesar Chavez, what he did and what he stood for, no matter whether you agreed with it all or not.

But apparently some people need to be reminded that he stood for peaceful, nonviolent action.

So, what does a replenishment ship "stand for?" It carries cargo and AMMUNITION. Bullets, bombs, rockets and grenades. The kind that soldiers use to kill foreigners. Mostly dark foreigners.

On the Bay City Television website, Secretary Mabus was quoted saying: "Cesar Chavez inspired young Americans to do what is right and what is necessary to protect our freedoms and our country." WRONG.

Yes, he inspired us "to do what is right." But the "what is right" was nonviolent protest against U.S. discrimination, which is basically the opposite of using lethal weapons against other countries' peoples.

Nor was he protecting "our freedoms." He was trying to secure civil rights for the North American working and poor who were denied their "freedoms," like the freedom to organize and the right to secure a decent living wage.

Nor was he protecting "our freedoms." He was trying to secure civil rights for the North American working and poor who were denied their "freedoms," like the freedom to organize and the right to secure a decent living wage.

Mabus also said, "The Cesar Chavez will sail hundreds of thousands of miles, and will bring support and assistance to thousands upon thousands of people. His example will live on in this great ship."

I could be wrong. Chavez might have once said he was "protecting our country." But what the USNS will carry will have nothing to do with preventing an invasion of the U.S. It will carry "support and assistance," not to any "people." The only "example that will live on" will be that it will carry weapons of death to soldiers.

Since