In honor of the 100th anniversary of World War I, we’re sharing an excerpt of Sir Hew Strachan’s The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War. Get a sense of what it was like to live through this historic event and how its global effects still impact the world today.

The Great War haunted the last century; it haunts us still. It continues to inspire imaginative endeavour of the highest order. It invites pilgrimage and commemoration surrounded by palpable sadness. Almost a hundred years after the war, ‘The Last Post’, intoned every evening at the Menin Gate in Ypres, still summons tears. We wish it all had not happened.

We associate the war with the loss of youth, of innocence, of ideals. We are inclined to think that the world was a better and happier place before 1914. If the last century has been one of disjunction and endless surprise rather than of the mounting predictability many expected at the next-to-last fin-de-siècle, the Great War was the greatest surprise of all. The war stands, by most historical accounts, as the portal of entry to a century of doubt and agony, to our dissatisfaction.

Its extremes of emotion, both the initial jubilation and subsequent despair, are seen as a preface to the politics of extremism that took hold in Europe in the aftermath; its mechanized killing is regarded as a necessary prelude to the even greater ferocity of the Second World War and to the Holocaust; its assault on the values of the Enlightenment is seen as a nexus between indeterminacy in the sciences and the aesthetics of irony. Monty Python might never have lived had it not been for the Great War. The war unleashed a floodtide of forces that we have been unable ever since to stem. ‘Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet, Lest we forget—lest we forget!’ How in the world, Mr Kipling, are we to forget?

Figure 11.1 from the Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War. Used with permissions from Oxford University Press.

The enthusiasm surrounding the outbreak of war many described as a social and spiritual experience beyond compare. Engagement was the hallmark of the day. ‘We have,’ wrote Rupert Brooke, ‘come into our heritage.’ The literate classes, and by then they were the literate masses—teachers, students, artists, writers, poets, historians, and indeed workers, of the mind as well as the fist—volunteered en masse. School benches and church pews emptied. Those past the age of military service enrolled in the effort on the home front.

Words, literary words, visible on the page, flowed as they had never flowed before, in the trenches, at home, and across the seven seas. The Berlin critic Julius Bab estimated that in August 1914 50,000 German poems were being penned a day. Thomas Mann conjured up a vision of his nation’s poetic soul bursting into flame. Before the wireless, before the television, this was the great literary war. Everyone wrote about it, and for it.

Not surprisingly, the Great War turned immediately into a war of cultures. To Britain and France, Germany represented the assault, by definition barbaric, on history and law. Brutality was Germany’s essence. To Germany, Britain represented a commercial spirit, and France an emphasis on outward form, that were loathsome to a nation of heroes. Treachery was Albion’s name. Hypocrisy was Marianne’s fame.

But the war was also an expression of social values. The intense involvement of the educated classes led to a form of warfare, certainly on the western front, characterized by the determination and ideals of those classes. Trench warfare was not merely a military necessity; it was a social manifestation. It was to be, in a sense, the great moral achievement of the European middle classes. It represented their resolve, commitment, perseverance, responsibility, grit—those features and values the middle classes cherished most.

And here for dear dead brothers we are weeping.

Mourning the withered rose of chivalry,

Yet, their work done, the dead are sleeping, sleeping

Unconscious of the long lean years to be.

Those lines from the Wykehamist, the journal of Winchester College, of July 1917 evoked both the passing of an age and the crisis of a culture.

‘The bourgeoisie is essentially an effort,’ insisted the French bourgeois René Johannet. The Great War was essentially an effort too. The American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald would call the war on the western front ‘a love battle—there was a century of middle-class love spent here. All my beautiful lovely safe world blew itself up here with a great gust of high-explosive love.’ Fitzgerald’s ‘lovely safe world’ was one of empire, imperial ideas, and imperial dreams. It was a world of confidence, of religion, and of history. It was a world of connections. History was a synonym for progress.

Sir Hew Strachan is a professor of the History of War at the University of Oxford, Commonwealth War Graves Commissioner, and a Trustee of the Imperial War Museum. He also serves on the British, Scottish, and French national committees advising on the centenary of the First World War. He is the editor of The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War.

We’re giving away ten copies of The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War to mark the 100th anniversary of World War I. Learn more and enter for a chance to win. For even more exclusive content, visit the US ‘World War I: Commemorating the Centennial’ page or UK ‘First World War Centenary’ page to discover specially commissioned contributions from our expert authors, free resources from our world-class products, book lists, and exclusive archival materials that provide depth, perspective, and insight into the Great War.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Memory and the Great War appeared first on OUPblog.

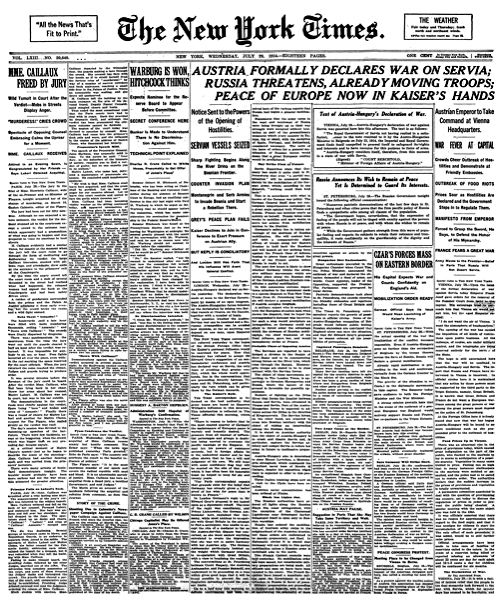

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

Before the sun rose on Wednesday morning a new hope for a negotiated settlement of the crisis was initiated. The Kaiser, acting on the advice of his chancellor, wrote directly to the Tsar. He hoped that Nicholas would agree with him that they shared a common interest in punishing all of those ‘morally responsible’ for the dastardly murder of the Archduke, and he promised to exert his influence to induce Austria to deal directly with Russia in order to arrive at an understanding.

At 1 a.m. Nicholas appealed to Wilhelm for his assistance: ‘An ignoble war has been declared on a weak country.’ The indignation that this had caused in Russia was enormous and he anticipated that he would soon be overwhelmed by the pressure being brought to bear upon him, forcing him to take ‘extreme measures’ that would lead to war. To avoid this terrible calamity, he begged Wilhelm, in the name of their old friendship, ‘to do what you can to stop your allies from going too far.’

The question of the day on Wednesday was whether Austria-Hungary and Russia might undertake direct discussions to settle the crisis before further military steps turned a local Austro-Serbian war into a general European one.

The German general staff summarized its view of the situation: the crime of Sarajevo had led Austria to resort to extreme measures ‘in order to burn with a glowing iron a cancer that has constantly threatened to poison the body of Europe’. The quarrel would have been limited to Austria and Serbia had not Russia begun making military preparations. Now, if the Austrians advanced into Serbia, they would face not only the Serbian army but the vastly superior strength of Russia. Thus, they could not contemplate fighting Serbia without securing themselves against an attack by Russia. This would force them to mobilize the other half of their army – at which point a collision between Austria and Russia would become inevitable. This would force Germany to mobilize, which would lead Russia and France to do the same – ‘and the mutual butchery of the civilized nations of Europe would begin’.

In other words, unless a negotiated settlement could be reached quickly, war seemed inevitable.

Berchtold pleaded with Berlin that only ‘plain speech’ would restrain the Russians, i.e. only the threat of a German attack would stop them from taking military action against Austria. And there were signs that Russia was wary of war. The Austrian ambassador reported that Sazonov was desperate to avoid a conflict and was ‘clinging to straws in the hope of escaping from the present situation’. Sazonov promised that if they were to negotiate on the basis of Sir Edward Grey’s proposal, Austria’s legitimate demands would be recognized and fully satisfied.

At the same time, Sazonov was pleading for British support: the only way to prevent war now was for Britain to warn the Triple Alliance that it would join its entente partners if war were to break out.

But Grey refused to make any promises. When he met with the French ambassador later that afternoon, he warned him not to assume that Britain would again stand by France as it had in 1905. Then it had appeared that Germany was attempting to crush France; now, ‘the dispute between Austria and Serbia was not one in which we felt called to take a hand’. Earlier that day the British cabinet had decided not to decide; Grey was to inform both sides that Britain was unable to make any promises.

At 4 p.m. the German general staff received intelligence that Belgium was calling up reservists, raising the numbers of the Belgian army from 50,000 to 100,000, equipping its fortifications and reinforcing defences along the frontier. Forty minutes later a meeting at the Neue Palais in Potsdam, the Kaiser and his advisers decided to compose an ultimatum to present to Belgium: either agree to adopt an attitude of ‘benevolent neutrality’ towards Germany in a European war or face dire consequences.

Simultaneously, Bethmann Hollweg decided to launch a bold new initiative. He proposed to the British ambassador that Britain agree to remain neutral in the event of war in exchange for a German promise not to seize any French territory in Europe when it ended. He understood that Britain would not allow France to be crushed, but this was not Germany’s aim. When asked whether his proposal applied to French colonies as well, the chancellor replied that he was unable to give a similar undertaking concerning them. Belgium’s integrity would be respected when the war ended –as long as it had not sided against Germany.

Yet another German initiative was taken in St Petersburg. At 7 p.m. the German ambassador transmitted a warning from the chancellor that if Russia continued with its military preparations Germany would be compelled to mobilize, in which case it would take the offensive. Sazonov replied that this removed any doubts he may have had concerning the real cause of Austria’s intransigence.

The Russians found this confusing, as they had just received another telegram from the Kaiser containing a plea that he should not permit Russian military measures to jeopardize German efforts to promote a direct understanding between Russia and Austria. It was agreed that the Tsar should wire Berlin immediately to ask for an explanation of the apparent discrepancy. At 8.20 p.m. the wire asking for clarification was sent. Trusting in his cousin’s ‘wisdom and friendship’, Tsar Nicholas suggested that the ‘Austro-Serbian problem’ be handed over to the Hague conference.

A message announcing a general mobilization in Russia had been drafted and ready to be sent out by 9 p.m. Then, just minutes before it was to be sent out, a personal messenger from the Tsar arrived, instructing that it the general mobilization be cancelled and a partial one re-instituted. The Tsar wanted to hear how the Kaiser would respond to his latest telegram before proceeding. ‘Everything possible must be done to save the peace. I will not become responsible for a monstrous slaughter’.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Wednesday, 29 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

There can be no area of human experience that has generated a wider range of powerful feelings than war. Jon Stallworthy’s celebrated anthology The New Oxford Book of War Poetry spans from Homer’s Iliad, through the First and Second World Wars, the Vietnam War, and the wars fought since. The new edition, published to mark the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War, includes a new introduction and additional poems from David Harsent and Peter Wyton amongst others. In the three videos below Jon Stallworthy discusses the significance and endurance of war poetry. He also talks through his updated selection of poems for the second edition, thirty years after the first.

Jon Stallworthy examines why Britain and America responded very differently through poetry to the outbreak of the Iraq War.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Jon Stallworthy on his favourite war poems, from Thomas Hardy to John Balaban.

Click here to view the embedded video.

As The New Oxford Book of War Poetry enters its second edition, editor Jon Stallworthy talks about his reasons for updating it.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Jon Stallworthy is a poet and Professor Emeritus of English Literature at Oxford University. He is also a Fellow of the British Academy. He is the author of many distinguished works of poetry, criticism, and translation. Among his books are critical studies of Yeats’s poetry, and prize-winning biographies of Louis MacNiece and Wilfred Owen (hailed by Graham Greene as ‘one of the finest biographies of our time’). He has edited and co-edited numerous anthologies, including the second edition of The New Oxford Book of War Poetry.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via

email or

RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via

email or

RSS.

The post What can poetry teach us about war? appeared first on OUPblog.

As we approach the 100th anniversary of the beginning of the First World War, it’s important taking a look back at the momentous event that forever changed the course of world history. Here, Sir Hew Strachan, editor of The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War, examines the importance of commemorating the Great War and how perspectives on the war have shifted and changed over the last 100 years.

What might we learn from the centenary commemoration of World War I?

Click here to view the embedded video.

What is the difference between commemorating the 50th anniversary and the centenary of the World War I?

Click here to view the embedded video.

What is the difference between the First and Second World Wars?

Click here to view the embedded video.

Sir Hew Strachan, Chichele is a Professor of the History of War at the University of Oxford, Commonwealth War Graves Commissioner, and a Trustee of the Imperial War Museum. He also serves on the British, Scottish, and French national committees advising on the centenary of the First World War. He is the editor of The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War. The first volume of his planned trilogy on the First World War, To Arms, was published in 2001, and in 2003 he was the historian behind the 10-part TV series, The First World War.

Visit the US ‘World War I: Commemorating the Centennial’ page or UK ‘First World War Centenary’ page to discover specially commissioned contributions from our expert authors, free resources from our world-class products, book lists, and exclusive archival materials that provide depth, perspective and insight into the Great War.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Reflections on World War I appeared first on OUPblog.